Sint-Salvatorsabdij | |

The abbey ruins, now a heritage site | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Order of Saint Benedict |

| Established | 1063 |

| Disestablished | 1795 |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Baldwin V, Count of Flanders, Adele of France |

| Architecture | |

| Status | ruin |

| Heritage designation | Provincial Archaeological Park |

| Designated date | 1998 |

| Site | |

| Coordinates | 50°51′29″N 3°37′44″E / 50.858°N 3.629°E |

| Public access | Free access to ruins. Provincial Archaeological Museum open Tuesday–Sunday, 9.30 a.m. to 5 p.m. (closed on Mondays and during the Christmas holidays) |

Ename Abbey (1063–1795) was a Benedictine monastery in the village of Ename, now a suburb of Oudenaarde. It was founded by Adele of France, wife of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders, and was confiscated during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was then sold and dismantled.

The archaeological development of the site began with the work of Adelbert Van de Walle in the 1940s. Since 1998 it has been part of the Provincial Archaeological Park attached to the provincial archaeological museum (PAM Ename).

History

.jpg.webp)

During the first half of the 11th century the tension between the Holy Roman Empire and the county of Flanders grew, especially in border territories. Ename was a stronghold on the river Scheldt that marked the border of the Empire.[2] In 1033 Baldwin V took possession of the keep and destroyed it; in 1047 the territory of Ename was definitively under his control. In order to demilitarise the area, in 1063 Adele of France founded the Abbey of Our Lady that received the village of Ename and other properties to provide financial income. The Benedictine abbey was established in the former Ottonian palace building, directed by a monk from the Saint Vedastus abbey in Arras. It was under the direct control of the Pope and through all its history it maintained a close relation with the counts of Flanders.

The construction of the abbey complex started immediately around the Saint Salvator church, formerly part of the village. Around 1070 the new abbey was finished and was founded a second time with the dedication to Saint Salvator. The previous palace building became then a chapel dedicated to Our Lady.[3]

In 1139 the Ottonian church of Saint Salvator was replaced by a bigger Romanesque church, inspired by the Benedictine abbeys of Cluny, Hirschau and Affligem. The abbey was flourishing as it had acquired many properties that provided a steady income. Around 1165 the abbey buildings were replaced by larger and more decorated buildings in the new Gothic style.

In the second half of the 13th century the abbey was extended with a hospital, and an infirmary for sick monks.

The woods around Ename had been intensively exploited. For this reason during the 13th century the abbey started a programme of forestry by planting trees and harvesting the wood. This action seems to be the oldest record of reforestation in Europe.[4][5]

During the 16th century, Europe and Flanders were shaken by revolts and civil wars provoked by an economic crisis and the diffusion of the Protestantism. Many religious buildings, including the abbey of Ename, were destroyed. Minor damage occurred during the 1566 Iconoclastic Fury, while the occupation of Oudenaarde by the Protestant troops of the city of Ghent in 1578 was disastrous for the abbey. The monks had to flee, the abbey buildings were plundered. Their ruins were used as a stone quarry until the return of the monks. In 1596 they started the rebuilding of the abbey. At the end of this period, more than half of the population of Ename had left their houses. With the return of the monks, the abbey reclaimed its property in the village and influence on the lives of the inhabitants of Ename. To emphasise this, a cross and a pillory were erected on the rectangular square of the village.

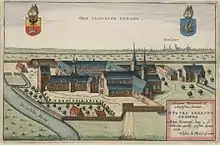

During the 17th century the abbey was very rich and its buildings were majestic. In 1657 abbot Antoon de Loose enlarged the abbot's quarters and also asked Pieter Hemony, a famous Dutch bell-founder, to cast the bells and the chimes for the carillon tower that he wanted at the entrance of the abbey. Abbot de Loose was a skilled manager of the abbey properties. Thanks to his accurate register, several details of everyday life are known today.[6]

Abbots were involved in the political life of the county as members of the States of Flanders. As it was forbidden to discuss political matters inside the walls of the abbey, a large, modern French garden with fountains and pavilions was built in front of the abbey. There it was possible for the abbots to meet other politicians and discuss affairs of state with them.

The abbey was dismantled in 1795, when the French Revolution arrived in Flanders. Today it is possible to visit the remains of the foundations in the Provincial archaeological park of Ename.

Archaeology

The archaeological excavations on the site of the abbey turned up several objects that today are on display in the Provincial Archaeological Museum (pam) in Ename. All the data collected by archaeological analysis, landscape archaeology, and historical research have been used to create 3D reconstructions showing the development of the site of the abbey over time. They are on display in the TimeScope application, which is open to the public on the archaeological site from April to November. The daily life of monks in the abbey during the 13th century can be experienced in the Provincial Heritage Centre through an interactive game and walkthrough 3D reconstruction.

Beer

Brewery Roman, a sponsor of the museum, brews a range of beers under the name Ename Abbey Beer.

References

- ↑ "Kaart van het grondbezit der adbij Ename in de parochies Welden, Ename en Nederename". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ↑ Dirk Callebaut, "Ename and the Ottonian west border policy in the middle Scheldt region", in Exchanging Medieval Material Culture: Studies on archaeology and history presented to Frans Verhaeghe Relicta Monografieën 4. Brussels, VIOE-VUB, 2010, pp. 217-248

- ↑ Ludo Milis, De onuitgegeven oorkonden van de Sint-Salvatorsabdij te Ename voor 1200 (Brussels, 1965)

- ↑ Guido Tack, Paul Van Den Bremt and Martin Hermy, "Bossen van Vlaanderen. Een historische ecologie", Leuven, Davidsfonds, 1993. Krtn., tab., ill., p. 230

- ↑ Geert Berings, "Landschap, geschiedenis en archeologie in het Oudenaardse", Stadsbestuur Oudenaarde, 1989, p. 187

- ↑ Guido Tack, Anton Ervynck, Gunther van Bost, De monnik-manager: Abt De Loose in zijn abdij t'Ename (Davidsfonds, 1999). ISBN 9789058260055

External links

- Website of PAM Ename(in Dutch), accessed 21 January 2015.

- Website of the Provincial Heritage Centre(in Dutch), accessed 18 March 2016.

- Visualisation of the Benedictine abbey of Ename, accessed 21 March 2016

- 3D models on Europeana