The Epistola consolatoria ad pergentes in bellum ("Letter of Consolation for Departing Warriors")[1] is an anonymous Latin sermon in epistolary form from the Carolingian period (8th–9th centuries).[2] It is addressed to a Christian army preparing for war against a non-Christian opponent.[3]

Genre

The Epistola is generally classified as a military sermon.[2][4][5][6] Albert Koeniger considered it one of the two earliest such works preserved in his study of the Carolingian military pastorate. Carl Erdmann, on the other hand, denied that it was a true sermon and, considering that its title is found in the manuscript, regarded it as simply a letter.[7] It may be a sermon that began as a letter of consolation to one being sent to war.[8] Michael McCormick suggests that it is part of a guidebook for military chaplains in the field.[9]

It is not known for certain if the Epistola was ever delivered as a sermon to assembled troops.[10] Bernard Bachrach thinks that the copy that survives may derive from notes taken by a cleric while a bishop was delivering the sermon to the army. This could then have circulated as a letter to serve as a model.[11]

Historical circumstances

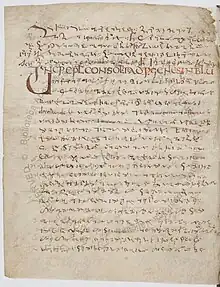

The manuscript Reg. lat. 846 in the Vatican Library preserves in Tironian shorthand the only known copy of the Epistola.[12] It contains 526 words and the shorthand copy is a mere 33 lines.[11] It has been expanded and published by Wilhelm Schmitz.[12] The manuscript has been dated as early as the 8th century and as late as the 830s, most commonly to the first quarter of the 9th century.[13]

There is less consensus on the date and circumstances of the sermon. Karl Künstle thought it originated in Visigothic Spain in the early 8th century, at the time of the Arab conquest.[14] In agreeing with Künstle, Alexander Bronisch sees parallels between the text and several Spanish texts, including Julian of Toledo's Story of Wamba (675) and the testament of Alfonso II of Asturias (812).[15] Koeniger associates it with Charles Martel's wars against the Arab invasion of Gaul in the 730s. Erdmann places it in the context of Viking raids in the 9th century.[1][2] David Bachrach accepts a dating to the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840).[5] McCormick initially accepted Koeniger's dating, but more recently puts the sermon in the 830s.[16]

Content

The sermon is written in a very simple Latin that was still comprehensible to many of the troops and in a highly repetitive style.[17] It begins, "Men, brothers and fathers, you who bear the Christian name and carry the banner of the cross on your brows, listen and hear."[18] It encourages the men individually to confess their sins to a priest and do penance before going into battle. The preacher sought to impart morale by stressing the soldiers' common bond in Christ and their obligation to defend his name.[19] It was for the defence of Christ's name and his churches that they went to war, not for worldly glory.[3][20] The war was thus, in a highly charged phrase, "Christ's battle" (praelium Christi).[1][21]

The sermon reminded the soldiers not to engage in sexual activity (concupiscentia karnale) or looting (rapinas). This applied on the march and in camp.[10] Foraging for food, however, was permitted out of military necessity.[22] Fighting with bravery and not cowardice was an obligation to God. That God would protect them and grant them victory was assured, but on the condition that they obeyed his laws, including the prohibitions on sexual activity and looting.[10] Piety was their shield and an angel would protect their camp. It was never required of a soldier to act against Christian law (contra legem Christianam) or the law of God (lex Dei).[20] Those who died in battle could be assured of paradise because, according to the final line of the sermon, "fight for God and God fights for you."[23]

The Epistola has been cited as an example of the "sacralization" of warfare under the Carolingians.[24] Bronisch, in his argument for a Visigothic dating, considers its sacral treatment of warfare highly atypical for the Carolingian period. He argues that, if it is indeed Carolingian, it should be seen as pointing forward to later developments but not representative of contemporary thinking.[25]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Erdmann 1977, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Verkamp 2006, p. 117n.

- 1 2 Coupland 1991, p. 550.

- ↑ Bachrach 2001, p. 348n.

- 1 2 Bachrach 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ McCormick 1992, cited in Bronisch 2006, p. 257.

- ↑ Erdmann 1977, p. 16n, citing Koeniger 1918.

- ↑ Bachrach 2003, p. 52n.

- ↑ Bachrach 2003, p. 52n, citing the talk upon which McCormick 2004 is based.

- 1 2 3 Bachrach 2003, p. 54.

- 1 2 Bachrach 2001, p. 156.

- 1 2 Schmitz 1896, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ "Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Reg. lat. 846", Bibliotheca Legum: A Database on Carolingian Secular Law Texts (Universität zu Köln). Accessed 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Erdmann 1977, p. 28, citing Künstle 1900.

- ↑ Bronisch 2006, pp. 259–263.

- ↑ Bronisch 2006, p. 261, citing McCormick 1992, and Bachrach 2003, p. 52n, citing the talk upon which McCormick 2004 is based.

- ↑ Bachrach 2001, p. 154.

- ↑ Bachrach 2003, p. 53. Latin in Bachrach 2001, p. 154: Viri, fratres et patres, qui christianum nomen habetis et vexillum crucis in fronte portatis, attendite et audite!

- ↑ Bachrach 2003, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 Bachrach 2001, p. 155.

- ↑ Bronisch 2006, p. 262.

- ↑ Bachrach 2001, p. 156 and 349n.

- ↑ Bachrach 2001, p. 155. Latin in Bronisch 2006, p. 260: Quidquid agitis pro Deo agite, et Deus pugnat pro vobis.

- ↑ Bronisch 2006, p. 261, citing McCormick 1992.

- ↑ Bronisch 2006, pp. 262–263.

Bibliography

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (2001). Early Carolingian Warfare: Prelude to Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bachrach, David S. (2003). Religion and the Conduct of War, c. 300–1215. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851159447.

- Bronisch, Alexander Pierre (2006) [1998]. Reconquista y guerra santa: La concepción de la guerra en la España cristiana desde los visigodos hasta comienzos del siglo XIII. Translated by Máximo Diago Hernando. Editorial Universidad de Granada.

- Coupland, Simon (1991). "The Rod of God's Wrath or the People of God's Wrath? The Carolingian Theology of the Viking Invasions". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 42 (4): 535–554. doi:10.1017/s0022046900000506. S2CID 162612436.

- Erdmann, Carl (1977) [1935]. The Origin of the Idea of Crusade. Translated by Marshall W. Baldwin and Walter Goffart. Princeton University Press.

- Koeniger, Albert Michael (1918). Die Militärseelsorge der Karolingerzeit: Ihr Recht und ihre Praxis. J. J. Lentner.

- Künstle, Karl (1900). "Zwei Dokumente zur altchristlichen Militärseelsorge". Der Katholik. 80 (2): 97–122.

- McCormick, Michael (1992). "Liturgie et guerre des Carolingiens à la première croisade". Militia Christi e Crociata nei secoli XI–XIII: Atti della undecima Settimana internazionale di studio, Mendola, 28 agosto – 1 settembre 1989. Milan. pp. 209–240.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - McCormick, Michael (2004). "The Liturgy of War from Antiquity to the Crusades". In Doris L. Bergen (ed.). The Sword of the Lord: Military Chaplains from the First to the Twenty-first Century. University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 45–67.

- Schmitz, Wilhelm (1896). Miscellanea Tironiana: Aus dem Codex vaticanvs latinvs, Reginae Christinae 846 (fol. 99–114). B. G. Teubner.

- Verkamp, Bernard J. (2006). The Moral Treatment of Returning Warriors in Early Medieval and Modern Times. University of Scranton Press.