Eugène Carrière | |

|---|---|

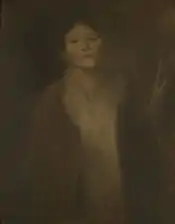

Self-portrait (c. 1893), oil on canvas Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| Born | 16 January 1849 Gournay-sur-Marne, France |

| Died | 27 March 1906 (aged 57) Paris, France |

| Known for | Painting, Lithography |

| Movement | Symbolism |

Eugène Anatole Carrière (16 January 1849 – 27 March 1906) was a French Symbolist artist of the fin-de-siècle period. Carrière's paintings are best known for their near-monochrome brown palette and their ethereal, dreamlike quality. He was a close friend of Auguste Rodin and his work likely influenced Pablo Picasso's Blue Period.[1][2] He was also associated with such writers as Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Morice.

Biography

The eighth of nine children of an insurance salesman, Carrière was born at Gournay-sur-Marne (Seine-Saint-Denis) and brought up in Strasbourg, where he received his initial training in art at the Ecole Municipale de Dessin as part of his apprenticeship in commercial lithography. In 1868, while briefly employed as a lithographer, he visited Paris and was so inspired by the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens in the Louvre that he resolved to become an artist. His studies under Alexandre Cabanel at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts were interrupted by the Franco–Prussian War, during which he was taken prisoner. In 1872–3 he worked in the studio of Jules Chéret. In 1878 he participated in the Salon for the first time, but his work went unnoticed. The following year he ended his studies under Cabanel, married Sophie Desmonceaux (with whom he would have seven children) and moved briefly to London where he saw and admired the works of J.M.W. Turner. Success eluded him for a number of years after he returned to Paris and he was forced to find occasional employment, usually with printers to support his growing family. Between 1880 and 1885 his brother Ernest (1858–1908), a ceramicist, arranged part-time work for him at the Sèvres porcelain factory. There he met Auguste Rodin who became and remained a very close friend.[3]

At the Salon of 1884 one of Carrière’s paintings received an honourable mention, and the influential art critic Roger Marx became a champion of his work. Thereafter, Carrière found friends in most of the important artists, critics, writers and collectors of his time. He was a founding member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and of the Salon d’Automne (of which he was named honorary president). He played an influential role as an art teacher at Académie de La Palette and also exhibited with the Libre Esthétique in Brussels (in 1894, 1896 and 1899), the Munich Secession (in 1896, 1899, 1905 and 1906) and the Berlin Secession in 1904, with works including Sleep (1890), the celebrated portrait of Paul Verlaine (1891, Luxembourg), Maternity (1892, Luxembourg), Christ on the Cross (1897), and Madame Menard-Dorian (1906).[4] Carrière died from throat cancer in 1906. The cultural world of Paris, from Georges Clemenceau to young artists such as Francis Picabia, was present at his funeral, where Rodin spoke of his "arresting ideas, expressed urgently and with a new clarity, undimmed by his suffering". Carrière's last words, recorded by his children, were: "Aimez-vous avec frénésie." ("Love each other wildly.") [5]

The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the Salon d’Automne in 1906, as well as the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the Libre Esthétique in 1907, held major retrospective exhibitions of Carrière's work.[6]

Style and influence

Carrière had great admiration for many of the Old Masters, but in his early work he was mainly influenced by his contemporary Jean-Jacques Henner. He increasingly used a near monochrome brown palette with occasional touches of other colours and a painterly technique somewhat like that of Henner, and by the mid-1880s his work was characterized by a dense, misty brown atmosphere out of which the images emerged.[7]

The Sick Child (1885; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) is an example of the theme of a mother and her child that Carrière often used and that has come to be regarded as typifying his work.[8]

Carrière occupies an important place in fin-de-siècle Symbolism, which developed in the visual arts from the mid-1880s. The quality of poetic, dreamlike reverie that pervades his work particularly appealed to Symbolist critics such as Charles Morice and Jean Dolent; the latter described Carrière’s art as reality having the magic of dreams. Carrière also frequented the Café Voltaire and was involved in Symbolist theatre, bringing him into the mainstream of Symbolism. By employing a subdued palette, softening the focus and enveloping his figures in a thick, dark atmosphere, as in Maternity (c. 1889; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.), Carrière achieved a rarified sense of space, light and colour. His ethereal images have a quality of pervasive stillness.

Carrière’s strong belief in the essential brotherhood of Man led him to consider his family as a microcosm of mankind. Though most of his paintings are of family members or family relationships, his interest in the universal rather than the specific usually resulted in figures without much individuality presented in a formless environment. He also produced a number of portraits, with notable examples being that of the poet Paul Verlaine (1890; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) and the sculptor Louis-Henri Devillez (1887).[9]

Several of his works can be found at the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée Rodin in Paris, the Tate in London and the National Museum of Serbia in Belgrade.

Selected paintings

Priam at the Feet of Achilles (1876), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Pau

Priam at the Feet of Achilles (1876), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Pau_-_Winding_Wool_(Les_D%C3%A9videuses)_-_L692_-_National_Gallery.jpg.webp) Winding Wool (1887), oil on canvas, 99.5 x 87.6 cm., National Gallery, London

Winding Wool (1887), oil on canvas, 99.5 x 87.6 cm., National Gallery, London Woman from Behind Undressing (c. 1890–95), oil on canvas 46.5 x 38.5 cm., collection unknown

Woman from Behind Undressing (c. 1890–95), oil on canvas 46.5 x 38.5 cm., collection unknown%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_220_x_490_cm.%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_Rodin%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) The Theater of Belleville (1895), oil on canvas, 220 x 490 cm., Musée Rodin, Paris

The Theater of Belleville (1895), oil on canvas, 220 x 490 cm., Musée Rodin, Paris Virgin at the Foot of the Cross (1897), oil on canvas, Strasbourg Museum of Modern Art

Virgin at the Foot of the Cross (1897), oil on canvas, Strasbourg Museum of Modern Art Le Réveil, Her Mother's Kiss (1899), oil on canvas, 94 x 120 cm., Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Le Réveil, Her Mother's Kiss (1899), oil on canvas, 94 x 120 cm., Pushkin Museum, Moscow The Mothers (1900). oil on canvas, 283.2 x 362.7 cm., Musée du Petit Palais, Paris

The Mothers (1900). oil on canvas, 283.2 x 362.7 cm., Musée du Petit Palais, Paris The Contemplator (1901), oil on canvas, 33.6 x 41 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

The Contemplator (1901), oil on canvas, 33.6 x 41 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio Landscape in the Orne (c. 1901), oil on prepared paper mounted on canvas, 32.7 x 41.3 cm., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence

Landscape in the Orne (c. 1901), oil on prepared paper mounted on canvas, 32.7 x 41.3 cm., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence

Portraits and figures

Portrait of a Boy (1886), oil on canvas, cm., Art Institute of Chicago

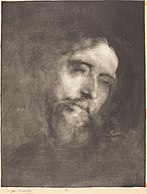

Portrait of a Boy (1886), oil on canvas, cm., Art Institute of Chicago%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_149.8x_121.9_cm.%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_du_Louvre%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Paul Verlaine (1890), oil on canvas, 149.8x 121.9 cm., Musée du Louvre, Paris

Paul Verlaine (1890), oil on canvas, 149.8x 121.9 cm., Musée du Louvre, Paris Portrait of Paul Gauguin (1891), oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Portrait of Paul Gauguin (1891), oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven Woman Leaning on a Table (1893), oil on canvas, 65 x 54.3 cm., The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg

Woman Leaning on a Table (1893), oil on canvas, 65 x 54.3 cm., The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg Woman Looking (date unknown), oil on canvas, 81 x 65,3 cm., Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

Woman Looking (date unknown), oil on canvas, 81 x 65,3 cm., Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires Two Women (c. 1895), oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Two Women (c. 1895), oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis Girl with Her Hair Down (1900–05), dimensions unknown, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm

Girl with Her Hair Down (1900–05), dimensions unknown, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm Arsène Carriere (1899-1900), oil on canvas, 55.56 × 46.36 cm., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Arsène Carriere (1899-1900), oil on canvas, 55.56 × 46.36 cm., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Prints and graphics

Newborn in a Bonnet (1890), lithograph, 25.5 x 19.2 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art

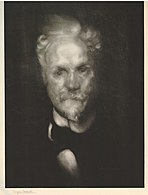

Newborn in a Bonnet (1890), lithograph, 25.5 x 19.2 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art Alphonse Daudet (1893), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Alphonse Daudet (1893), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Henri Rochefort (1896), lithograph, British Museum, London

Henri Rochefort (1896), lithograph, British Museum, London Paul Verlaine (1896), lithograph, 52 x 40.6 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art

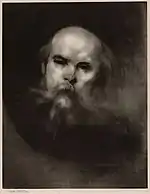

Paul Verlaine (1896), lithograph, 52 x 40.6 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art Puvis de Chavannes (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Puvis de Chavannes (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Rodin (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Rodin (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Sleep (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Sleep (1897), lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Jean Dolent (1898), lithograph, 22.9 x 17 cm., British Museum, London

Jean Dolent (1898), lithograph, 22.9 x 17 cm., British Museum, London Mlle Marguerite Carrière Singing (1901), litograph, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm

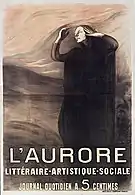

Mlle Marguerite Carrière Singing (1901), litograph, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm Poster: Literary, Artistic, Aocial Aurore (1898), Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Poster: Literary, Artistic, Aocial Aurore (1898), Bibliothèque Nationale de France

See also

References

- ↑ Rojas, Carlos; Marbán, Dorothy (1993). "Picasso and Tolstoy: On Life, Love and Death". The Comparatist. University of North Carolina Press. 17: 4–5. JSTOR 44364084 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Anonymous (30 October 2018). "The Contemplator". Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ Bantens, Robert J. (2003), "Carrière, Eugène", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t014419, retrieved 27 December 2021

- ↑ Bantens, Robert (1989). Eugene Carriere: The Symbol of Creation. New York: Kent Fine Art.

- ↑ Hollis, Richard (26 August 2006). "Richard Hollis on painter Eugène Carrière". the Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ Bantens, Robert J. (2003), "Carrière, Eugène", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t014419, retrieved 27 December 2021

- ↑ "Little d'Artagnan". www.clarkart.edu. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Bantens, Robert J. (2003), "Carrière, Eugène", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t014419, retrieved 27 December 2021

- ↑ Louis-Henri Devillez in his Studio, by Eugène Carrière, 1887, tumblr.com

Further reading

- Séailles, Gabriel (1901). Eugéne Carrière, l'homme et l'artiste: Compositions et croquis de E. Carriére gravés par Mathie. Paris: Pelletan.

- Geffroy, Gustave (1901). L'oeuvre de E. Carrière (The Works of E. Carrière). Paris: H. Piazza.

- Morice, Charles (1906). Eugéne Carrière: L'homme et sa pensée; l'artiste et son œuvre; essai de nomenclature des oeuvres principales. Paris: Société du Mercure de France.

- Faure, Elie (1908). Eugéne Carrière, peintre et lithographe. Paris: H. Floury.

- Musée d'Orsay; Kokuritsu Seiyo Bijutsukan (National Museum of Western Art) (2006). Auguste Rodin; Eugène Carrière. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-011626-0.

- Agnès, Lauvinerie; Eduardo Leal de la Gala (2006). Moi, Eugène Carrière. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Eugène Carrière at the Museum of Modern Art

- Eugène Carrière: Symbols of Creations Exhibition at Kent Fine Art, New York

- Musée Virtuel Eugène Carrière

- Hollis, Richard. "Ghostly realist", The Guardian, August 26, 2006

- Paintings at Beauty and Ruin

- Paintings at Artcyclopedia

- Eugène Carrière at Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Connecticut