| Common periwinkle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Periwinkle emerging from its shell, Sweden | |

| |

| L. littorea on the edge of a small sandy beach in Woods Hole, Massachusetts | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Caenogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Family: | Littorinidae |

| Genus: | Littorina |

| Species: | L. littorea |

| Binomial name | |

| Littorina littorea | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The common periwinkle or winkle (Littorina littorea) is a species of small edible whelk or sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusc that has gills and an operculum, and is classified within the family Littorinidae, the periwinkles.[2]

This is a robust intertidal species with a dark and sometimes banded shell. It is native to the rocky shores of the northeastern, and introduced to the northwestern, Atlantic Ocean.

Description

The shell is broadly ovate, thick, and sharply pointed except when eroded.[3] The shell contains six to seven whorls with some fine threads and wrinkles. The color varies from grayish to gray-brown, often with dark spiral bands.[3] The base of the columella is white.[3] The shell lacks an umbilicus. The white outer lip is sometimes checkered with brown patches. The inside of the shell is chocolate brown.

The width of the shell ranges from 10 to 12 millimetres (3⁄8 to 1⁄2 in) at maturity,[4] with an average length of 16 to 38 mm (5⁄8 to 1+1⁄2 in).[3] Shell height can reach up to 30 to 52 mm (1+1⁄8 to 2 in),[4][5][3] The length is measured from the end of the aperture to the apex. The height is measured by placing the shell with the aperture flat on a surface and measuring vertically.[6]

L. littorea can be highly variable in phenotype, with several different morphs known. Its phenotypic variations may be indicative of speciation, as opposed to phenotypic plasticity. This is of particular importance to evolutionary biology, as it may represent an opportunity to observe a transitional phase in the evolution of an organism.[7]

Life cycle

L. littorea is oviparous, reproducing annually with internal fertilization of egg capsules that are then shed directly into the sea, leading to a planktotrophic larval development time of four to seven weeks.[8] Females lay 10,000 to 100,000 eggs contained in a corneous capsule from which pelagic larvae escape and eventually settle to the bottom.[9] This species can breed year round depending on the local climate.[9] Benson suggests that it reaches maturity at 10 mm and normally lives five to ten years.[9] while Moore suggests that maturity is reached in 18 months.[10] Some specimens have lived 20 years.

Female specimens have been observed to be ripe from February until end of May, when most are spawning. Male specimens are mainly ripe from January until the end of May and lose weight after copulation. The young seem to settle primarily from the end of May to the end of June, although other sources indicate earlier settlement.[10]

Growth rate

A study in Plymouth Sound suggests an initial growth reaching up to 14 mm (1⁄2 in) in height December the first year, and 17.4 mm (5⁄8 in) by the end of the second year. Females seem to grow more rapidly than males, and in specimens above 25 mm (1 in) in height, females seem to dominate.[10] Another study undertaken in Blackwater Estuary, Essex showed growth reaching up to 8 mm (3⁄8 in) the first winter.[11]

Distribution

Common periwinkles are native to the northeastern coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, including northern Spain, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Russia, and Nigeria.[9]

There have been more than 14,000 observations made available as a dataset at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility - Littorina littorea,[12] which can be explored. More distribution information can also be found at Ocean Biographic Information System - Littorina littorea.[13] The NBN Gateway - Littorina littorea has a distribution map over the UK and Ireland.[14] These datasets may overlap.

Introductions to North America

Common periwinkles were introduced to the Atlantic coast of North America, possibly by rock ballast in the mid-19th century.[15] This species is also found on the west coast of the United States, from Washington to California. The first recorded sighting in the East was in 1840 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[15] It is now abundant on rocky shores from New Jersey northward to Newfoundland.[9][8] In Canada, its range includes New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador.[3]

L. littorea is now the most common marine snail along the North Atlantic coast. It has changed North Atlantic intertidal ecosystems via grazing activities, altering the distribution and abundance of algae on rocky shores and converting soft-sediment habitats to hard substrates, as well as competitively displacing native species.[9][8]

Ecology

Habitat

The common periwinkle is mainly found on rocky shores in the higher and middle intertidal zone.[9] It sometimes lives in small tide pools. It may also be found in muddy habitats such as estuaries[9] and can reach depths of 55 metres (180 feet).[9] When exposed to either extreme cold or heat while climbing, a periwinkle will withdraw into its shell and start rolling, which may allow it to fall to the water.[16]

Zone

Movement both horizontally and vertically in response to light and dark as well as temperatures have been observed, but over a short timespan the movement seems to be random.

Experiments seem to indicate that the snail responds to light and current, and moves accordingly.[17]

Feeding

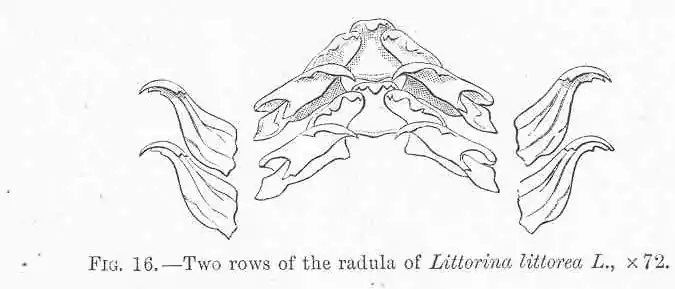

L. littorea is an omnivorous, grazing intertidal gastropod.[8] It is primarily an algae grazer, but it will feed on small invertebrates such as barnacle larvae. It uses its radula to scrape algae from rocks and, in the salt marsh community, pick up algae from cord grass or from the biofilm that covers the surface of mud in estuaries or bays. Macroalgae that are readily consumed include Ulva lactuca and Ulva intestinalis;[18] if provided, blue mussel can also be eaten.

The radula is taenioglossate, consisting of seven teeth per row: one middle tooth, flanked on each side by one lateral and two marginal teeth. The radula is used to scrape algae and detritus.

Phlorotannins in the brown algae Fucus vesiculosus and Ascophyllum nodosum act as chemical defenses against L. littorea.[19]

Parasites

The common periwinkle can act as a host for various parasites, including Renicola roscovita, Cryptocotyle lingua, Microphallus pygmaeus and Himasthla sp. More studies are needed before any conclusions regarding the effect of parasites on growth can be reached. It seems that growth rate is primarily affected on available food and time available for feeding, rather than parasites.[20]

Polydora ciliata has also been found to excavate burrows in the shell of the common periwinkle when the snail is mature (above 10 mm long). The reason why this happens only to mature snails is not yet known, but one hypothesis is that a mature snail will excrete a signal substance which attracts the P. ciliata larvae. Another hypothesis is that a mature snail has a change in the shell surface that makes it suitable for P. ciliata larvae to settle. The infection by this parasite does not seem to alter the growth and proportions of the snail shell.[21]

Mortality

A mortality rate of up to 94% per annum has been observed for the first two months, followed by up to 60% per annum for the rest of the first year:

...out of every 950 shells of all ages [collected] at that time, 850 are first year, and 100 are in their second or subsequent year.[22]

Older individuals above 15 months old seem to have a mortality of only 23% per annum. Cercaria emasculans is known to be fatal to the snail, but this does not account for the observed mortality.[10]

Human use

This species appears in prehistoric shellfish middens throughout Europe, and is believed to have been an important source of food since at least 7500 B.C.E. in Scotland.[23] It is still collected in quantity in Scotland, mostly for export to the Continent and also for local consumption. The official landings figures for Scotland indicate over 2,000 tonnes of winkles are exported annually. This makes winkles the sixth most important shellfish harvested in Scotland in terms of tonnage, and seventh most important in terms of value. However, since actual harvests are probably twice reported levels, the species may actually be the fourth and sixth most important, respectively.[24]

Periwinkles are usually picked off the rocks by hand or caught in a drag from a boat. They are mostly eaten in the coastal areas of Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland, where they are commonly referred to as winkles or in some areas buckies, willicks, or wilks. In Belgium, they are called kreukels or caracoles.

They are commonly sold in paper bags near beaches in Ireland and Scotland, boiled in their local seawater, with a pin attached to the bag to enable the extraction of the soft parts from the shell.

Periwinkles are considered a delicacy in African and Asian cuisines. The meat is high in protein, omega-3 fatty acids and low in fat; according to the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, raw snails in general are about 80% water, 15% protein, and 1.4% fat.

Periwinkles are also used as bait for catching small fish. The shell is usually crushed and the soft parts extracted and put on a hook.

In accordance with their history as an ancient food source in Atlantic Europe, they are harvested and consumed in the Azores Islands by the Portuguese people, where they are usually called búzios, the generic name for sea snails.

The record for the farthest a human has spat a winkle was 10.4 metres by Alain Jourden (France) in 2006.[25]

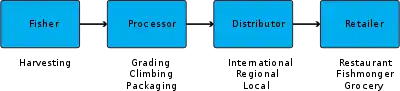

Supply chain

As for seafood supply chains in general, the supply chain consists of a collector, processor, distributor and finally the retailer. The true nature of the supply chain is usually more complex and opaque, with the potential for records of harvesting areas and date of catch to be falsified.

Collection

Commonly harvested in buckets by workers walking in the intertidal zone on low tide; other methods have been tried.

In Maine, the snails are commonly collected by a dredge towed from a vessel.

In Norway, snorkeling has also been used.

A report on the state of the periwinkle industry in Ireland suggests a maximum catch size in order to preserve the population.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Processor

The processor buys in bulk from the collector, involving a possibly long transport route by land in a refrigerator truck or airplane, taking care to avoid temperatures below 0°C.

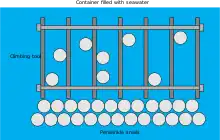

If fresh seawater is readily available, the periwinkles are first graded if possible, using a machine custom built for the purpose. The method used for grading differs, but two proven methods include a Trommel screen with horizontal bars instead of a mesh, and a circle-throw vibrating machine also using bars. The price to purchase a complete sorting machine can be €10,000 or more.

Periwinkles are graded by number of snails per kilogram. The following table displays some common grades in France. The actual value depends upon supply and demand, with seasonal variations. The actual ranges may also differ from each establishment.

| Grade name | Number per kilogram |

|---|---|

| Small | Unknown |

| Medium | Unknown |

| Large | 180–240 |

| Jumbo | 140–180 |

| Super Jumbo | 90–140 |

After grading, the periwinkles are "climbed" close to the consumer, which involves checking whether they are still alive. This can take anywhere from a few hours to several days, depending on how healthy the periwinkles are and the temperature of the water they climb in. Any periwinkles left immobile at the bottom are considered dead and are discarded. It is not uncommon to have up to 8% waste in a shipment.

Hereafter, the winkles are commonly packed in smaller quantities before being distributed to customers. Mesh bags from 3 to 10 kg are common.

Distributor

To sell large quantities, distributors are commonly used to move the periwinkles to the retailer. These have networks of transport available both internationally, regionally and locally inside a city. Several distributors are usually involved in the complete journey, each focusing on its own part of the transport network.

Retail

The common periwinkle is sold by fishmongers at seafood markets in large cities around the world, and is also commonly found in seafood restaurants as an appetizer or as a part of a seafood platter. In some countries, pubs may serve periwinkles as a snack.

Most of the volume fished is consumed by France, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands.

Methods to increase commercial value

Ongrowing has been investigated as a potential way of increasing commercial value, but no documented pilot facilities have been established. By harvesting the periwinkle during the summer and storing them with feed until December, not only should the grade have been increased, but the market value should be higher since supply is lower in the cold winter months.[26]

Aquaculture

Raising the common periwinkle has not been a focus due to its abundance in nature and relatively low price; however, there are potential benefits from aquaculture of this species, including a more controlled environment, easier harvesting, less damages from predators, as well as saving the natural population from commercial harvesting.

Packaging

Commonly packed in 3 kg boxes by the processor, the box is usually polystyrene foam or thin wood, depending on the market demands. Holes in the box ensures that any water lost by the snails drains out, so that they remain in better condition for longer. A label indicates the fishing zone, packaging date, and any other information required by law.

Storing

In a fridge, the common periwinkle can usually be stored for up to a week, but this may vary depending on how long they have been stored prior to sale, and how they have been kept since the moment they are fished. As long as they are kept moist and cold, they can survive well for a longer period of time. It is not recommended to store at temperatures below 0 degrees Celsius, even if research has shown a Median Lower Lethal Temperature of -13.0 degree Celsius.[27] Even if the common periwinkle survives when put back into seawater, they seem to be unable to move and climb.

See also

References

This article incorporates a public domain text (a public domain work of the United States Government) from references [9][3] and CC-BY-2.5 text from the reference [8]

- ↑ Linnaeus C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. pp. [1–4], 1–824. Holmiae. (Salvius).

- 1 2 Reid, David G.; Gofas, S. (2011). Littorina littorea (Linnaeus, 1758). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=140262 on 2011-05-16

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Benson A. J. (2011). Littorina littorea. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=1009 Archived 2012-02-23 at the Wayback Machine RevisionDate: 4/21/2009.

- 1 2 Common periwinkle at marlin.ac.uk retrieved 20.04.2016

- ↑ Welch J. J. (2010). "The "Island Rule" and Deep-Sea Gastropods: Re-Examining the Evidence". PLoS ONE 5(1): e8776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008776.

- ↑ Eschweiler, N., Molis, M. & Buschbaum, C. Helgol Mar Res (2009) "Habitat-specific size structure variations in periwinkle populations (Littorina littorea) caused by biotic factors" doi:10.1007/s10152-008-0131-x

- ↑ Grahame J. (1975). "Spawning in Littorina littorea (L.) (Gastropoda: Prosobranchiata)". Journal of experimental marine Biology and Ecology 18: 185–196.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chang A. L., Blakeslee A. M. H., Miller A. W. & Ruiz G. M. (2011). "Establishment Failure in Biological Invasions: A Case History of Littorina littorea in California, USA". PLoS ONE 6(1): e16035. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016035.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Benson A. (2008). Littorina littorea. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. <https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.asp?speciesID=1009 Archived 2009-06-01 at the Wayback Machine> Revision Date: 8/20/2007

- 1 2 3 4 The biology of Littorina littorea. Part 1. Growth of the shell and tissues, spawning, length of life and mortality. Hillary B. Moore,Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, Volume 21, Issue 2, 1937, pages 721-742

- ↑ Report on the Maldon (Essex) Periwinkle Fishery. F.S. Wright, Great Britain. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. Fishery Investigations. Ser. II, Vol. 14, no. 5 & 6., 1936

- ↑ Global Biodiversity Information Facility - Littorina Littorea

- ↑ Ocean Biographic Information System - Littorina Littorea

- ↑ "NBN Gateway - Littorina Littorea". Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- 1 2 Chapman J. W., Carlton J. T., Bellinger M. R. & Blakeslee A. M. H. (2007). "Premature refutation of a human-mediated marine species introduction: the case history of the marine snail Littorina littorea in the northwestern Atlantic". Biological Invasions 9:737-750.

- ↑ "Edible periwinkle - Encyclopedia of Life".

- ↑ The Biology of Rocky Shores, page 94 By Colin Little, J. A. Kitching

- ↑ The Biology of Rocky Shores, page 83, Colin Little, J. A. Kitching

- ↑ Polyphenols in brown algae Fucus vesiculosus and Ascophyllum nodosum: Chemical defenses against the marine herbivorous snail, Littorina littorea. J. A. Geiselman and O. J. McConnell, Journal of Chemical Ecology,1981, Volume 7, Number 6, pages 1115-1133, doi:10.1007/BF00987632

- ↑ Influence of trematode infections on in situ growth rates of Littorina littorea. Kim N. Mouritsen, A. Gorbushin O and K. Thomas Jensen, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, Volume 79, Issue 3, 1999, pages 425-430

- ↑ On the shell growth of Littorina Littorea and the occurrence of Polydora Ciliata. Lars Orrhage, Zoologiska bidrag från Uppsala, Volume 38, 1969, pages 137-152

- ↑ Moore, Hilary B. (March 1937). "The Biology of Littorina littorea. Part 1. Growth of the Shell and Tissues, Spawning, Length of Life and Mortality". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 21 (2): 739. doi:10.1017/S0025315400053844. S2CID 53869716. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ Ashmore, quoted in McKay and Fowler 1997 b

- ↑ McKay and Fowler 1997 b

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World Records 2014. pp. 221. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ↑ "Documents" (PDF).

- ↑ Davenport, John; Davenport, Julia L. (May 2005). "Effects of shore height, wave exposure and geographical distance on thermal niche width of intertidal fauna" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 292: 41–50. Bibcode:2005MEPS..292...41D. doi:10.3354/meps292041.

Further reading

- Abbott, R. T. (1974). American Seashells. Second edition. New York: Van Nostrand Rheinhold.

- Abbott, R. T. (1986). Seashells of North America. New York: St. Martin's Press.

External links

- Littorina littorea (mollusc) Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine from the Invasive Species Specialist Group website of the World Conservation Union

- Common periwinkle from the Marine Life Information Network for Britain and Ireland

- Invertebrate Anatomy OnLine: Littorina irrorata from a Lander University website

- Photos of Common periwinkle on Sealife Collection