Exercise Bright Star is a series of biennial combined and joint military exercises led by the United States and Egypt. The exercises began in 1980, rooted in the 1977 Camp David Accords. After its signing, the United States Armed Forces and the Egyptian Armed Forces agreed to conduct training together in Egypt.[1]

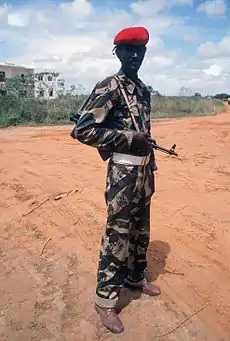

Bright Star is designed to strengthen ties between the Egyptian Armed Forces and the United States Central Command and demonstrate and enhance the ability of the Americans to reinforce their allies in the Middle East in the event of war. These deployments are usually centered at the large Cairo West Air Base. Since the Gulf War, the end of NATO's Cold War-era Reforger exercises, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Bright Star exercises have grown larger and have included as many as 11 countries and 70,000 personnel. Other allied nations joining Bright Star exercises in Egypt include the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, Jordan, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and formerly the Somali Democratic Republic.

The exercise begins with coalition interoperability training to teach nations how to operate with one another in a wartime environment, then continues with a Command Post Exercise designed to help standardize command and control procedures, and then a large-scale Field Training Exercise to practice everything together.

Early exercises

The first exercise, Bright Star 81, was conducted from October to December 1980 (fiscal year 1981). The U.S. Army's rapid-deployment unit (Task Force "Strike", 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment) of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) and U.S. Air Force (USAF) personnel were deployed to Cairo West Air Base in Egypt for the exercise. This operation was the first deployment of combat soldiers into the region since World War II. Bright Star 81 was initiated by the Carter administration in response to the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet–Afghan War. However, U.S. forces proved to be unprepared for the exercise: soldiers were issued jungle fatigues in lieu of desert camouflage (which was not in the U.S. Army inventory in 1980), and hastily-established air traffic control systems caused the loss of 14 USAF personnel when a C-141 Starlifter crash-landed. Post-operation briefings affected positive change for future readiness and successful exercises thereafter.

The following year, a similar exercise was held using the same ground rules. USS Coral Sea (CV-43) took part in Bright Star 82. After Exercise Eastern Wind 83, the amphibious portion of Bright Star 83, the Los Angeles Times was told that "the exercise failed dismally ... 'The Somali army did not perform up to any standard,' one diplomat said. … 'The inefficiency of the Somali armed forces is legendary among foreign military men.'"[2]

The Sudanese Armed Forces participated in the exercise in 1981 and 1983.[3]

By 1983, the size of the forces involved prompted planners to hold the event every two years rather than annually. The exercise went under further evolution in 1985 with the inclusion of the USAF and Egyptian Air Force. The two nations' respective navies and special forces joined the exercise in 1987.

The Associated Press, in a story dated August 4, 1985, said that U.S. forces would begin their largest-ever exercise in the Middle East that day. Egypt, Somalia, Jordan, and Oman were reported as participating.[4]

Egypt's Information Ministry confirmed that Bright Star began in Egypt on schedule with activation of command centers and some movement of troops into maneuver areas. A Pentagon spokesman in Washington said about 9,000 Americans would take part in the weeklong Egyptian phase, the main part of the exercise. The spokesman said an unspecified smaller number of American soldiers would take part in Somalia and about 520 would join in the Jordanian portion. Pentagon sources in Washington said a smaller number of Americans would also train in Oman.

After the 1989 event, the exercise was moved from the summer to the fall.

Bright Star 95

In the Autumn of 1995, nearly 60,000 troops took part in the revived Bright Star Exercise, which included nations other than Egypt and the United States for the first time.

Bright Star 97

During the 1997 exercise, the U.S. Air Force encountered a fuel shortage. Their Egyptian counterparts demonstrated an ability to blend Jet A-1 fuel with additives to produce the JP-8 required by U.S. aircraft.

Bright Star 98

The 1998 event focused on naval and amphibious warfare. It included the USS George Washington, USS John F. Kennedy Battle Groups and the Guam Amphibious Ready Group.

Bright Star 99

The largest Bright Star exercise took place in October and November 1999, involving 11 nations and 70,000 personnel. An additional 33 nations sent observers to monitor the exercise: Algeria, Australia, Bahrain, Belgium, Burundi, Canada, China, Congo, Greece, India, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Poland, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Syria, Tanzania, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

The exercise scenario involved a fictional hostile nation named "Orangeland" invading Egypt and trying to take control of the Nile River. The exercise coalition worked together, practicing fighting in the air, land, and sea domains, to defend the Nile and expel Orangeland.

A key piece of the training was a six-nation amphibious assault led by the Royal Navy.

Bright Star 01

Despite the September 11 attacks, the U.S. sent 23,000 troops to participate in Bright Star in October and November 2001. Elements of the 1st Infantry Division and 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment joined coalition partners to continue strengthening U.S.-Arab ties.

Forces from Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, Spain and the United Kingdom participated in the event.

It was the first time in the history of the United States that a military exercise was executed under Force Protection Condition 'Delta'.

Quartermaster Professional Bulletin Spring 2002 gives detail about the efforts of the 559th Quartermaster Battalion to support Bright Star 01.

The National Command Authorities deemed this exercise so important that it continued the operation which began just days before terrorists struck targets on American soil on September 11, 2001.

Planning for the USAF portion of Operation Bright Star 2001 started months earlier at Shaw Air Force Base at the United States Air Force Central Command (CENTAF) headquarters. While Operation Bright Star was a military exercise, the security issues surrounding the exercise were very real. With much of the exercise planned for taking place in Cairo and other Egyptian locations, security considerations involved addressing terrorist activity in that region of the world. Since the very nature of the exercise was the US-led coalition of nations acting to protect the middle east and the free flow of oil to the rest of the world, potential targeting of this activity by terrorist was a major concern. The USAF called upon its newly formed Force Protection unit to oversee both the planning and execution of security for the Air Force portion of Bright Star. Following the 1996 terrorist bombing of Khobar Towers, targeting, and killing US military personnel housed in the city of Khobar, Saudi Arabia, the Air Force had formed a dedicated force protection unit, the 820th Security Forces Group, capable of global deployment and containing dedicated specialties crucial to force protection under one commander. In August of 2000, LtCol John Hursey, then Deputy Commander for the 820th was assigned to the CENTAF-led planning staff. It was also planned that Hursey would command the 820th staff and resources deployed in support of Bright Star. This included a large contingent of active duty and reserve US Air Force personnel in the Cairo area as well as a joint USAF and USMC unit at a remote Egyptian base housing deployed USAF and USMC fighter aircraft. During previous Bright Star exercises, critical deployed US military units were generally housed in military compounds, protected by U.S., Egyptian, and coalition forces. However, the initial planning for this Bright Star was considering housing all US participants in hotels rather than military compounds.

Following the October 2000 terrorist attack on the USS Cole in Yemen's Aden Harbor, USAF Bright Star planners abandoned the plans for housing all participants in hotels and opted for the traditional joint US-Egyptian protected military compounds. The 820th Security Forces Group-led security for Bright Star, involved significant perimeter security, electronic surveillance, and a large contingent of US and Egyptian forces. While the exercise was not set to begin until late September of 2001, there was a significant presence of US, Egyptian, and other coalition forces preparing for the upcoming exercise at the time of the September 11th terrorist attacks. While still in the advance stages of preparation, Hursey and USAF Bright Star Commander Col Dodson <additional info needed> watched on live TV the as second tower was stuck by an aircraft. Upon Hursey's recommendation and coordination with US Military and State Department staff, Dodson declared THREATCON DELTA for the USAF Bright Star Operations in Egypt. Fortunately, advance planning for Bright Star by US, Egyptian, and coalition forces included worst case scenarios of operating in high threat environments so that personnel, resources, and procedures could be quickly amassed to provide adequate protection in these advanced threat conditions.

Bright Star 04

The U.S. did not participate in the exercise scheduled for Fall 2003 due to high military commitments in the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War.

Bright Star 06

Bright Star 06 began on September 10, 2005, and ended October 3, 2005. The Pennsylvania Army National Guard’s 28th Infantry Division (Mechanized) was put in charge of the field training exercise. Units participating included 28th ID’s 104th Cavalry Regiment, Marines from the 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit, mechanized infantry from Jordan, and a tank company from Egypt. In addition, 11 Airmobile Infantry Battalion Garderegiment Grenadiers en Jagers of the Royal Netherlands Army deployed to Egypt for the exercise.[5] Also among the many military units was the 256th Combat Support Hospital which is an Army Reserve unit from Columbus, Ohio and the 140th Quartermaster unit from Fort Totten, NY. The 256th CSH served in support of the many jump operations that were conducted. The Aviation Task Force was led by the Wisconsin and Iowa Army National Guard's 1-147th Command Aviation Battalion supported by MEDEVAC units from California and Wyoming. CH-47 Chinooks were provided by the Connecticut Army National Guard

Bright Star 08

Among the U.S. participants for Bright Star 08 were the 42nd Infantry Division of the New York Army National Guard, the only U.S. National Guard division headquarters to have deployed to Iraq at that time, and the 48th Brigade Special Troops Battalion of the Georgia Army National Guard.

Bright Star 10

Bright Star 10 took place in October 2009 which included a strategic airborne jump of more than 300 Soldiers from the 82nd Airborne Division partnering with Egyptian, German, Kuwaiti, and Pakistani paratroopers, while more than 1,000 Marines from the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit rolled onto El Alamein Beach by amphibious landing with their Bright Star counterparts.[6]

Also more non-traditional training took place during the operation and included a combined computer aided command post exercise introducing partnering soldiers to each other's equipment and updated tactics, thereby developing a better coalition contingency environment.[6]

Bright Star 12

Bright Star 12 was postponed due to the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.[7]

Bright Star 14

Bright Star 14, which should have taken place in September 2013, was cancelled by U.S. president Barack Obama after Egyptian police raided two large encampments by supporters of ousted president Mohamed Morsi in Cairo to forcibly disperse them, after six weeks of unauthorized sit-in.[7]

Bright Star 17

Bright Star 17 took place in Western Alexandria's Mohammed Naguib Military Base[1] [8] [9] [10][11] [12] from September 10th to September 20th 2017.

Bright Star 18

Bright Star 18 was conducted between September 8th and September 20th in Western Alexandria's Mohammed Naguib Military Base, with forces from Greece, Jordan, Italy, France, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates, as well as observers from 16 other nations. [13][14][15]

Bright Star 21

Bright Star 21 took place at Mohammed Naguib Military Base in Marsa Matruh from September 2nd to September 16th, 2021. Military groups from the following nations joined the U.S. and Egypt in Bright Star 2021: Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, Bahrain, Sudan, Morocco, Kuwait, UAE, Tunisia, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, Greece, and Pakistan. The exercise was originally scheduled for 2020 but was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. [16][17]

Bright Star 23

The next bright star exercise was hosted in 2023, as confirmed by the Egyptian embassy in Washington D.C.[18] The exercise was taken place form August 27 to September 16, 2023, at Cairo (West) Air Base in Egypt. The Indian Air Force took part in Ex BRIGHT STAR-23 for the first time along with contingents from the US, Saudi Arabia, Greece, and Qatar. [19]

Footnotes

- 1 2 "Egypt to host 'Operation Bright Star 2017' military drill with US army". en.africatime.com.

- ↑ Charles Mitchell (17 March 1985). "U.S. Losing Interest in Military Bases in Somalia: Port, Airstrip No Longer Are Key Part of Plans for Gulf of Aden Emergency". Los Angeles Times. UPI. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ↑ Ofcansky 2015, p. 346.

- ↑ AROUND THE WORLD: GI's in the Mideast Start Big War Games, Associated Press, New York Times, August 5, 1985

- ↑ Leo van Westerhoven (8 September 2005). "Oefening Bright Star 2005, Grenadiers vooraan in zinderend Egypte". www.dutchdefencepress.com. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- 1 2 Operation Bright Star begins October 16, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- 1 2 Lawler, David (15 August 2013). "Barack Obama cancels Operation Bright Star" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ "Mohammed Naguib Military Base: The Biggest Military Base in Africa - The Best of Africa- African politics and development". 28 July 2017.

- ↑ "All you need to know about 'Mohamed Naguib' military base - Egypt Today". www.egypttoday.com. 22 July 2017.

- ↑ "The new 'Naguib military base' should make us weep for Egypt". 25 July 2017.

- ↑ Mohy, Bahaa (26 July 2017). "Inauguration of Mohamed Naguib Military Base: Reportedly the largest in the Middle East".

- ↑ "Egypt's Sisi opens biggest military base in Middle East and Africa". 22 July 2017.

- ↑ "Mohammed Naguib Military Base hosts one of the largest military exercises in the region". NYAG SPC Goins, Robert during operation bright star. 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "U.S. participates in Exercise Bright Star in Egypt". United States Central Command. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

U.S. military forces will join the Egyptian armed forces for Exercise Bright Star 2018 at Mohamed Naguib Military Base, Egypt, Sept. 8 - 20 [, 2018]. Approximately 800 U.S. military service will participate in this exercise for the second year in a row. The focus this year will be on regional security and cooperation, and promoting interoperability in irregular warfare scenarios.

- ↑ "Exercise Bright Star 2018 Opening Ceremony". U.S. Army Central. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ↑ "U.S. forces participate in Exercise Bright Star in Egypt". U.S. Embassy in Egypt. 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ↑ "Egypt, 20 countries conclude 'Bright Star 2021' military exercise at Mohamed Naguib Military Base in Marsa Matrouh". EgyptToday. 2021-09-17. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ↑ https://egyptembassy.net/news/100_years/exercise-bright-star-a-definitive-statement-of-strategic-partnership-between-egypt-and-the-u-s/

- ↑ https://capsindia.org/exercise-bright-star-23-global-military-diplomacy-at-its-best/

- Ofcansky, Thomas P. (2015). "Foreign Military Assistance". In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan: a country study (PDF) (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.