| National Trunk Highway System 中国国家干线公路系统 Zhōngguó Guójiā Gànxiàn Gōnglù Xìtǒng | |

|---|---|

The sign of regional expressway S1 for Gansu Province and the sign of national expressway G3 Beijing-Taipei Expressway below | |

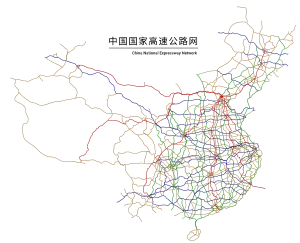

A map of the national expressways of China | |

| System information | |

| Maintained by Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China | |

| Length | 168,000 km (2021) (104,000 mi) |

| Formed | 7 June 1984 |

| Highway names | |

| Expressways: | GXX (National expressways) GXXxx (Auxiliary National expressways) SXX (Regional expressways) |

| System links | |

| Expressways of China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国国家干线公路系统 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國國家幹線公路系統 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngguó Guójiā Gànxiàn Gōnglù Xìtǒng | ||||||

| Literal meaning | China National Highway System | ||||||

| |||||||

The expressway network of China, with the national-level expressway system officially known as the National Trunk Highway System (Chinese: 中国国家干线公路系统; pinyin: Zhōngguó Guójiā Gànxiàn Gōnglù Xìtǒng; abbreviated as NTHS), is an integrated system of national and provincial-level expressways in China.[1][2]

With the construction of the Shenyang–Dalian Expressway beginning between the cities of Shenyang and Dalian on 7 June 1984, the Chinese government started to take an interest in a national expressway system. The first modern at-grade China National Highways is the Shanghai–Jiading Expressway, opened in October 1988.[note 1] The early 1990s saw the start of the country's massive plan to upgrade its network of roads.[1][3] On 13 January 2005, Zhang Chunxian, China's Minister of Transport introduced the 7918 network, later renamed the 71118 network, composed of a grid of 7 radial expressways from Beijing, 9 north–south expressways (increased to 11), and 18 east–west expressways that would form the backbone of the national expressway system.[2][4]

By the end of 2020, the total length of China's expressway network reached 161,000 kilometres (100,000 mi),[5] the world's largest expressway system by length, having surpassed the overall length of the American Interstate Highway System in 2011.[6] Note, it is not longer than the entire federal US numbered highway system which is 259,032 kilometers long and American State Highways both of which includes many roads that are up to the expressway standards (but also some that are not). Planned length of China's National Trunk Highway System is 168,478 kilometres (104,687 mi) by 2020. Many of the major expressways parallel routes of the older China National Highways. By the end of 2022, the total length of China's expressway network reached 177,000 kilometres (110,000 mi),[7]

History

| Year[note 2] | Length |

|---|---|

| 1988 | 0 km (0 mi) |

| 1989 | 147 km (91 mi) |

| 1990 | 271 km (168 mi) |

| 1991 | 522 km (324 mi) |

| 1992 | 574 km (357 mi) |

| 1993 | 652 km (405 mi) |

| 1994 | 1,145 km (711 mi) |

| 1995 | 1,603 km (996 mi) |

| 1996 | 2,141 km (1,330 mi) |

| 1997 | 3,422 km (2,126 mi) |

| 1998 | 4,771 km (2,965 mi) |

| 1999 | 8,733 km (5,426 mi) |

| 2000 | 11,605 km (7,211 mi) |

| 2001 | 16,314 km (10,137 mi) |

| 2002 | 19,453 km (12,088 mi) |

| 2003 | 25,200 km (15,700 mi) |

| 2004 | 29,800 km (18,500 mi) |

| 2005 | 34,300 km (21,300 mi) |

| 2006 | 41,005 km (25,479 mi) |

| 2007 | 45,339 km (28,172 mi) |

| 2008 | 53,913 km (33,500 mi) |

| 2009 | 60,436 km (37,553 mi) |

| 2010 | 65,055 km (40,423 mi) |

| 2011 | 74,113 km (46,052 mi) |

| 2012 | 84,946 km (52,783 mi) |

| 2013 | 96,200 km (59,800 mi) |

| 2014 | 104,438 km (64,895 mi) |

| 2015 | 111,936 km (69,554 mi) |

| 2016 | 123,523 km (76,754 mi) |

| 2017 | 130,973 km (81,383 mi) |

| 2018 | 136,500 km (84,800 mi) |

| 2019 | 142,500 km (88,500 mi) |

| 2020 | 149,600 km (93,000 mi) |

| 2021 | 161,000 km (100,000 mi) |

| 2022 | 168,000 km (104,000 mi) |

Origins

Prior to the 1980s, freight and passenger transport activities were predominantly achieved by rail transport rather than by road. The 1980s and 1990s saw a growing trend toward roads as a method of transportation and a shift away from rail transport. In 1978, rail transport accounted for 54.4 percent of the total freight movement in China, while road transport only accounted for 2.8 per cent. By 1997, road transport's share of freight movement had increased to 13.8 percent while the railway's share decreased to 34.3 percent. Similarly, road's share of passenger transport increased from 29.9% to 53.3% within the same time period, with railway's share decreasing from 62.7 percent to 35.4 percent. The shift from rail to road can be attributed to the rapid development of the expressway network in China.[1]

Expressways were not present in China until 1988.[10] On 7 June 1984, China's expressway ambitions began when construction of the Shenyang–Dalian Expressway began between the cities of Shenyang and Dalian. Due to policy restrictions, the expressway was nominally implemented on the first-grade automobile special highway standard in the initial stage of construction, thus making the highway technically not an expressway. Despite this, in October 1988, four years later, two full-speed, fully enclosed, controlled-accessed expressway sections from Shenyang to Anshan and Dalian to Sanshilipu totaling 131 kilometres (81 mi) were completed, with the 108 kilometres (67 mi) middle portion of the expressway remaining a highway. It would take until 20 August 1990, for all sections of the highway to become that of an expressway. The expressway is now part of the longer G15 Shenyang–Haikou Expressway.[3]

On 21 December 1984, construction began on the Shanghai–Jiading Expressway in the city of Shanghai. The Shanghai–Jiading Expressway opened on 31 October 1988, becoming the first completed expressway in China. This 17.37 kilometres (10.79 mi) expressway now forms part of Shanghai's expressway network. In December 1987, construction of the 142.69-kilometre (88.66 mi) long Jingjintang Expressway started, connecting the municipalities of Beijing and Tianjin, and the province of Hebei. It the first expressway in mainland China that uses a World Bank loan for international open bidding. The expressway was opened on 25 September 1993 and later became part of the G2 Beijing–Shanghai Expressway.[3]

On 3 September 1998, Huabei Expressway Co., Ltd., Northeast Expressway Co., Ltd., Hunan Changyong Expressway Co., Ltd., and Guangxi Wuzhou Transportation Co., Ltd. were approved by the government as the first batch of nationally issued stock companies that would develop, construct, and operate expressways in China.[11][12][13]

Modernization

On 13 January 2005, Zhang Chunxian, China's Minister of Transport announced that China would build a network of 85,000 kilometres (53,000 mi) expressways over the next three decades, connecting all provincial capitals and cities with a population of over 200,000 residents. The announcement introduced the 7918 network, a grid of 7 radial expressways from Beijing, 9 north–south expressways, and 18 east–west expressways that would form the backbone of the national expressway system.[2] This replaced the earlier proposal for five north–south and seven east–west core routes, proposed in 1992.[1]

In June 2013, the Ministry of Transport introduced the National Highway Network Planning, covering both the national highway system and the national expressway system from 2013 to 2030. Goals include making traffic travel more convenient and developing a variety of regions, as well as more focus to the highways and expressways of the western regions of China. According to this plan, the total size of the national road network will reach 400,000 kilometres (250,000 mi), including 265,000 kilometres (165,000 mi) of common national highways and about 118,000 kilometres (73,000 mi) of expressways. In addition, the 7918 network would be renamed the 71118 network when the number of north–south expressways were increased from 9 to 11. Huang Min, director of the Basic Industry Department of the Development and Reform Commission, said that whether the plan is for ordinary national roads, the development of expressways is prioritized more in the western regions. According to Huang, the two expressways were to be added to the western region, while none in the northern, eastern, or southern regions.[4]

_Xinjiang%252C_China_-_panoramio_(9).jpg.webp)

In 2014, Wang Tai, deputy director of the Highway Bureau of the Ministry of Transport, introduced the national toll highway mileage and mainline toll stations.[14]

On 6 November 2015, Hu Zuicai, deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, introduced a reform policy for construction of China's expressway system that was approved by the State Council. Hu claimed that the current highway construction is facing problems such as pre-approval and evaluation assessment. Through simplification and integration of examination and approval stages, it will help speed up the pace of highway construction, promote urban development in the region, and help stabilize growth and promote investment. This policy, during the “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” period, would focus on five aspects:[15]

- Speeds up the building of expressways, especially to link the broken roads between the provinces as soon as possible, and to play the overall role of the expressway system;

- Supports the three major strategies and strengthen the important domestic and inter-provincial channels of the international economic cooperation corridor, connecting important coastal highways along the coast of the Yangtze River and linking the construction of important port highways;

- Serves new urbanization and urban agglomerations, and connecting cities and cities within urban agglomerations between cities and cities is the key to construction;

- Supports poverty alleviation and cracks down on poverty by linking between cities and regions;

- Efforts are made to improve the efficiency of transportation, so that the freeway and other modes of transport can be seamlessly connected or transferred and the overall transportation efficiency can be improved.

In 2020, all toll booths at provincial borders were abolished in favour of ETC, greatly reducing traffic congestion.[16][17]

In 2022, the NDRC and MOT published a new National Highway Network Plan (Chinese: 国家公路网规划), added and re-formed several expressways and national highways. It is expected that all national expressways will connect prefecture-level administrative regions (except Sansha), other cities and counties with 100,000 and more populations, and important border checkpoints.[18]

Safety

In 2008 the rate of fatalities on Chinese expressways is 3.3 fatalities per 100 million vehicle-km. Nonetheless, the fatality rate on Chinese expressways is five times higher than western countries which have a 0.7 rate.[19] In 2010 the total expressway mileage accounted for only 1.85 percent of highway mileage driven, however accidents on expressways made up 13.54% of highway traffic deaths.[20] For the 2011-2015 period this was still at 10%.[21] The accidents are mainly caused by tailgating, fatigue and speeding.[22]

Expressway nomenclature

Neither officially named "motorway" nor "highway", China used to call these roads "freeways". In this sense, the word "free" means that the traffic is free-flowing; that is, cross traffic is grade separated and the traffic on the freeway is not impeded by traffic control devices like traffic lights and stop signs. Some time in the 1990s, "expressways" became the standardised term.

Note that "highways" refers to China National Highways, which are not expressways at all.

"Express routes" exist too; they are akin to expressways but are mainly inside cities. The "express route" name is a derivation of the Chinese name kuaisu gonglu (compare with expressway, gaosu gonglu). Officially, "expressway" is used for both expressways and express routes, which is also the standard used here.

The names of the individual expressways are regularly composed of two characters representing start and end of expressway, e.g. "Jingcheng" expressway is the expressway between "Jing" (meaning Beijing) and Chengde.

Speed limits

The Road Traffic Safety Law of the People's Republic of China stipulates the speed limit of 120 km/h (75 mph), effective since 1 May 2004.

A minimum speed limit of 60 km/h (37 mph) is in force. On overtaking lanes, however, this could be as high as 110 km/h (68 mph).[23] Penalties for driving both below and in excess of the prescribed speed limits are enforced.

Some expressways have a lower design speed of 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph).[24]

Legislation

Only motor vehicles are allowed to enter expressways. As of 1 May 2004, "new drivers" (i.e., those with a Chinese driver's licence for less than a year) are allowed on expressways, something that was prohibited from the mid-1990s.

Overtaking on the right, speeding, and illegal use of the emergency belt (or hard shoulder) cost violators stiff penalties.

Signage

Expressways in China are signed in both Simplified Chinese and English (except for parts of the Jingshi Expressway, which relies only on Chinese characters, and some provinces, in Inner Mongolia for example signs are in Mongolian and Chinese, and in Xinjiang the signs are in Chinese and Uyghur Language which uses Perso-Arabic alphabet).

The signs on Chinese expressways use white lettering on a green background, like Japanese highways, Italian autostrade, Swiss autobahns and United States freeways. Newer signage places the exit number in an exit tab to the upper right of the sign, making them very similar in appearance to American freeway signs.

Exits are well indicated, with signs far ahead of exits. There are frequent signs that announce the next three exits. At each exit, there is a sign with the distance to the next exit. Exit signs are also posted 3,000 m (9,800 ft), 2,000 m (6,600 ft), 1,000 m (3,300 ft), and 500 m (1,600 ft) ahead of the exit, immediately before the exit, and at the exit itself.

Service areas and refreshment areas are standard on some of the older, more established expressways, and are expanding in number. Gas stations are frequent.

Signs indicate exits, toll gates, service/refreshment areas, intersections, and also warn about keeping a fair distance apart. "Distance checks" are commonplace; the idea here is to keep the two-second rule (or, as Chinese law requires, at least a 100 m (330 ft) distance between cars). Speed checks and speed traps are often signposted (in fact, on the Jingshen Expressway in the Beijing section, even the cameras have a warning sign above them), but some may just be scarecrow signs. Signs urging drivers to slow down, warning about hilly terrain, banning driving in emergency lanes, or about different road surfaces are also present. Also appearing from time to time are signs signaling the overtaking lane (which legally should only be used to pass other cars). Although most English signs are comprehensible, occasionally the English is garbled.

Many expressways have digital displays. These displays may advise against speeding, indicate upcoming road construction, warn of traffic jams, or alert drivers to rain. Recommended detours are also signaled. The great majority of messages are only in Chinese.

Exit numbering

_Duyun_Direction_Exit_332_close_to_G75.jpg.webp)

Exit numbering has been standardised in China from its inception. Most Chinese expressways, especially those in the national network, use distance-based exit numbering, with the last three numbers before the decimal point taken used as the exit number. Hence, an exit at km 982.7 would be Exit 982, whereas an exit at km 3,121.2 would be Exit 121. Exit numbers on Chinese expressways increase along the total length of the freeway, regardless of how many provincial boundaries the expressway crosses.[25]

Some, mostly regional, expressways still use sequential exit numbering, although even here, new signage feature distance-based exit numbering. Before the 2009–2010 numbering switchover, nearly all of China's expressways used sequential numbering, and a few expressways used Chinese names outright.

One of the reasons for this shift is that distance-based exit numbering comes in handy when newly built exits are added to an expressway exit system. If sequential numbering is used, numbers of all the exits following the new exit have to be replaced, which will be a troublesome and costly project. But that will not be a problem for distance-based exit numbering.

The exit is written inside an oval in green letters to the immediate right of the Chinese word for exit, "出口" (chukou).

Financing

.jpg.webp)

Costs

The total costs of the national expressway network are estimated to be 2 trillion yuan (some US$300 billion as rate in 2016). From 2005 to 2010, the annual investment was planned to run from 140 billion to 150 billion yuan (17 to 18 billion U.S. dollars), while from 2010 to 2020, the annual investment planned is to be around 100 billion yuan.

The construction fund will come from vehicle purchase tax, fees and taxes collected by local governments, state bonds, domestic investment and foreign investment. Unlike other freeway systems, almost all of the roads on the NTHS/"7918 Network" are toll roads that are largely financed by private companies under contract from provincial governments. The private companies raise money through bond and stock offerings and recover money through tolls. Examples of these companies include Huabei Expressway Co., Ltd., Northeast Expressway Co., Ltd., Hunan Changyong Expressway Co., Ltd., and Guangxi Wuzhou Transportation Co., Ltd.[11][12][13]

Efforts to impose a national gasoline tax to finance construction of the tollways met with opposition and it has been very difficult for both the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council to pass such a tax through the National People's Congress of China.[26][27]

Tollways

China has an extensive tollway system, which composed of nearly all expressways as well as having around 70% of the world's tollways.[28] Tolls are roughly around CNY 0.5 per kilometer, and minimum rates (e.g. CNY 5) usually apply regardless of distance. However, some are more expensive (the Jinji Expressway costs around CNY 0.66 per kilometer) and some are less expensive (the Jingshi Expressway in Beijing costs around CNY 0.33 per kilometer). It is noteworthy that cheaper expressways do not necessarily mean poorer roads or a greater risk of traffic congestion.

Roads in Tibet and Hainan are all toll free. In Tibet, this is done to stimulate economic development, whereas in Hainan, the cost is covered by a provincial fuel tax, first instated in 1994.[29][30] Tolls are waived nationwide during national holidays, such as Golden Week, and regionally for locally observed holidays. For example, Xinjiang makes all expressway travel free during Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.

Expressway planning is performed by the Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China. Unlike the road networks in most nations, most Chinese expressways are not directly owned by the state, but rather are owned by for-profit corporations (which have varying amounts of public and private ownership) which borrow money from banks or securities markets based on revenue from projected tollways. Examples of these corporations include Huabei Expressway Co., Ltd., Northeast Expressway Co., Ltd., Hunan Changyong Expressway Co., Ltd., and Guangxi Wuzhou Transportation Co., Ltd.[11][12][13] One reason for this is that Chinese provinces, which are responsible for road building, have extremely limited powers to tax and even fewer powers to borrow.

Since the late-1990s, there were proposals to fund public highways by means of a fuel tax, but this was voted down by the National People's Congress.[26][27]

China's tollways were criticized for having excessively high toll fees.[28] According to Zhongxin.com, by reducing toll fees, it will lead to logistic costs reductions, another problem encountered by the country's expressway system.[31] Reforms of the tollway system were planned by the National People's Congress with the inclusion of cost reduction of bridges.[32]

Methods

Most expressways use a card system. Upon entrance to an expressway (or to a toll portion of the expressway), an entry card is handed over to the driver. The tolls to be paid are determined from the distance traveled when the driver hands the entry card back to the exit toll gate upon leaving the expressway. A small number of expressways do not use a card system but charge unitary fares. Passage through these expressways is relatively faster but it is economically less advantageous. An example of such an expressway would be the Jingtong Expressway.[33]

China is increasingly deploying a network of electronic toll collection (ETC) systems, and in the latest edition of expressway toll gate signage, a new ETC sign is now shown at an increasing number of toll gates. ETC networks based around Beijing,[34] Shanghai,[35] and Guangdong province[36] all feature either mixed toll passages supporting toll card payment or full-service dedicated ETC lanes. Beijing, in particular, has a dedicated ETC lane at almost all toll gates.[37] By 2019, 90% of traffic paid is expected to pay toll fees using the ETC system.[38]

City transit cards are not widely used; one of the first experiments with the Beijing Yikatong Card on what is now the Jingzang Expressway (G6)[39] went live for only a year before a new national standard replaced it in early 2008.

Numeric system and list by number

Radial line North–South line East–West line

Zonal ring line (Dot line: Planned)

G000 series

A previous system, the 1992 "five vertical + seven horizontal expressways" system, was used for arterial expressways and were, in essence, G0-series expressways (e.g. G020, G025). This was replaced by the present-day new numeric system (see below).

New numbering system

A new system, which dates from 2004 and began use on a nationwide level between late 2009 and early 2010, integrates itself into the present-day G-series number system. The present-day network announced in 2017, termed the 7, 11, 18 Network (also known as the National Trunk Highway System, NTHS), uses one, two or four digits in the G-series numbering system, leaving three-figured G roads as the China National Highways.

The new 7, 11, 18 Network is composed of

- 7 radial expressways leaving Beijing (G1-G7)

- 11 vertical expressways going north to south (double digit G roads with numbers ending in an odd numeral)

- 18 horizontal expressways head west to east (double digit G roads with numbers ending in an even numeral)

The network is additionally composed of connection expressways as well as regional and metropolitan ring expressways.

On a nationwide basis, expressways use the G prefix (short for "guojia" in Chinese meaning "national"), as well as the character "国家高速" (National Expressway, white letters on a red stripe on top of the sign). For regional expressways, the prefix S (short for "shengji" or "provincial") is used instead, as well as the one-character abbreviation of the province and "高速" (expressway, black letters on an orange-yellow stripe on top of the sign.) The same numbering system is used for both national and regional expressways.

Numbering rules

- All expressways in this network begin with the letter G. (For regional expressways, the letter S is used instead.)

- All expressways have a thin band on top of the sign. For national expressways, it will be red; for regional ones, it will be orange-yellow.

- For radial expressways leaving from or ending in Beijing, use a single digit from 1 to 9 (e.g., G1, G2).

- For north–south expressways, use an odd number from 11 to 89 (e.g., G11, G35).

- For west–east expressways, use an even number from 10 to 90 (e.g., G20, G36).

- For regional ring expressways in the 7, 11, 18 network, use numbers from 91 to 99 (e.g., G91, G93)

- Note: G99 or the Taiwan Ring Expressway is currently a proposed expressway based in Taiwan Province, which is claimed by the People's Republic of China, but is actually administered by the Republic of China. (In addition, the ROC has not built the eastern half as an expressway.) See Political status of Taiwan. See also Highway system in Taiwan for the current Republic of China-maintained Taiwan freeway system, which uses a different numbering system.

- For city ring expressways, use "0" plus an order number after the main line number, starting from the smallest possible number (e.g., G5001).

- For connection expressways, use an odd numeral plus an order number after the main line (e.g., G9411).

- For the parallel expressways running alongside primary ones, use an even numeral (except "0") plus an order number after the main line (e.g. G0422, here the corresponding main line with a single digit should follow a "0" to distinguish from CNH).

National Trunk Highway System Expressways

Regional Expressways

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Shanghai–Jiading Expressway was the first expressway to be built in Mainland China, excluding Taiwan (see Political status of Taiwan), as well as Hong Kong and Macau, which were under British and Portuguese control respectively at the time. If Taiwan is included, the first expressway to open in modern China was Taiwan's National Highway 1, known as the Zhongshan Expressway, which opened in 1974.

- ↑ Length of network as of 1 January of the respective year.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Li, Si-ming and Shum, Yi-man. Impacts of the National Trunk Highway System on accessibility in China Archived 22 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Transport Geography.

- 1 2 3 国家高速公路网规划 (National Trunk Highway System Planning) Archived 2014-01-14 at the Wayback Machine. 13 January 2005. (in Chinese)

- 1 2 3 国内首条取消收费高速公路改建工程启动 Archived 2016-01-08 at the Wayback Machine. News.cn. (in Chinese)

- 1 2 "未来公路建设向西部倾斜 有助改变区域经济发展-中新网". Chinanews.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "多项指标位居世界第一 我国从"交通大国"迈向"交通强国"". 新华网. 31 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ "我国高速公路通车里程位居世界第一 骨架网络正加快贯通". 第一财经日报. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "数说中国 我国高速公路通车里程稳居世界第一". 新华网.

- ↑ National Bureau of Statistics of China Archived 2009-03-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "交通运输行业晒出2016年度成绩单". Gov.cn. 17 April 2017. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ↑ "USATODAY.com - China's highways go the distance". usatoday30.usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Huabei Expressway Co., Ltd.: Private Company Information". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Northeast Expressway Co. Ltd.: Private Company Information". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Guangxi Wuzhou Transportation Construction Development Co Ltd: Company Profile". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "全国收费公路里程达16.26万公里 共有收费站1665个-中新网". Chinanews.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "我国高速路年底或超12万公里". Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "China to Eliminate Manned Toll Booths on Provincial Borders - Caixin Global". Caixinglobal.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ "China sees improved road transport efficiency after expressway toll booths removal | english.scio.gov.cn". English.scio.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ "国家发展改革委 交通运输部关于印发《国家公路网规划》的通知". Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China. 12 July 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ↑ "World Bank. "China—Road Traffic Safety: The Achievements, the Challenges, and the Way Ahead." (2008)" (PDF). Openknowledge.worldbank.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Zhao, Jinbao; Deng, Wei (May 2012). "Traffic Accidents on Expressways: New Threat to China". Traffic Injury Prevention. 13 (3): 230–238. doi:10.1080/15389588.2011.645959. ISSN 1538-9588. PMID 22607245. S2CID 9499968. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ Wang, Bing; Wu, Chao (30 November 2019). "Using an evidence-based safety approach to develop China's road safety strategies". Journal of Global Health. 9 (2): 020602. doi:10.7189/jogh.09.020602. PMC 6858991. PMID 31777659. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ Research Institute of Highway Ministry of Transport, China-Sweden Research Centre for Traffic Safety. The Blue Book of Road Safety in China 2015. Beijing: China Communications Press; 2016.

- ↑ "高速120突然限速60公里,很多人不懂怎么办?这次讲清楚". 29 September 2019. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021.

- ↑ "高速上限速80,开到88算超速么?不清楚的可能会吃亏!". Article_2004950194.

- ↑ "国家高速公路网编号规则-常见留言-中华人民共和国交通运输部". Mot.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- 1 2 "China bites the bullet on fuel tax". Rsc.org. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 "BBC News". Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 "高速公路还完贷款不应再收费--中国高速公路网". China-highway.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ sina_mobile (6 January 2020). "中国有两个地方没有收费站,也不收高速费,其中一个就是西藏". k.sina.cn. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "不够精准、不够公平,通行附加费到底该怎么收?-新华网". Xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "中国物流费用占GDP达16% 多地实施高速公路降费_网易新闻". News.163.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "李克强:深化收费公路制度改革 降低过路过桥费用_中国公路网". Chinahighway.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "明年起使用ETC卡交纳通行费不再开纸质发票_中国公路网". Chinahighway.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "ETC速通卡客服网站". Bjetc.cn. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Archived July 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "首页 - 粤通卡门户网站". 96533.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ "365条ETC车道开通,基本实现全市收费站点全覆盖". Bjetc.cn. 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ↑ "国务院办公厅关于印发深化收费公路制度改革取消高速公路省界收费站实施方案的通知(国办发〔2019〕23号)_政府信息公开专栏". Gov.cn. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "北京八达岭高速"速通卡"将停止使用". News.sohu.com. 3 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

.jpg.webp)