| Fedexia Temporal range: Late Pennsylvanian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Family: | †Trematopidae |

| Genus: | †Fedexia Berman et al., 2010 |

| Species | |

| |

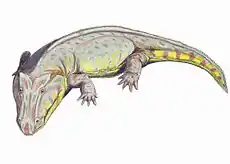

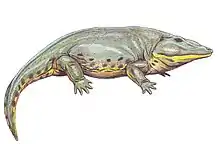

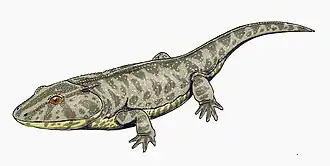

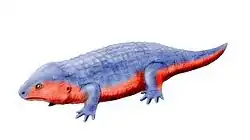

Fedexia is an extinct genus of carnivorous temnospondyl within the family Trematopidae.[1] It lived 300 million years ago during the late Carboniferous period. It is estimated to have been 2 feet (0.61 m) long, and likely resembled a salamander.[2] Fedexia is known from a single skull found in Moon Township, Pennsylvania. It is named after the shipping service FedEx, which owned the land where the holotype specimen was first found.[3]

Discovery

The holotype skull (CM 76867) was discovered on land owned by the FedEx Corporation near the Pittsburgh International Airport in 2004. Adam Striegel, a student at the University of Pittsburgh, found the skull on a field trip to the area, but he mistook the teeth for a fern frond. It was later recognized as a skull by class lecturer Dr. Charles Jones, and was taken to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for further study. The specific name of the type species honors Adam Striegel.[3]

The area where the holotype was discovered was part of the Casselman Formation of the Conemaugh Group. In North American Carboniferous stratigraphy, these strata are early Virgilian in age. According to ICS standards, they are Gzhelian in age. The skull itself was found lying near the base of a road cut that exposes the lower part of the Casselman Formation. The Casselman Formation overlies the Ames Limestone, which represents the last marine submergence of the Appalachian Basin.[4] The earliest portions of the Casselman Formation, consisting of sandstones and siltstones, are overbank levee deposits that were formed at the shoreline of the retreating Ames Sea. Overlying these deposits is the Grafton Sandstone, a cross-bedded channel-phase sandstone deposited by a meandering river. Above the sandstone lies the Birmingham Shale, which includes fine-grained siltstone and shale overbank deposits. A thick paleosol is present at the top of the Birmingham Shale, and it is capped by limestone that is of freshwater lacustrine (lake) origin.[1]

The holotype skull likely came from the limestone that caps the Birmingham Shale or the underlying paleosol. Because it was not found in situ, the horizon in which the skull originated cannot be determined definitively. The gray limestone matrix that is found inside the skull has been examined by geochemical X-ray reflectance analyses. However, these analyses were not able to determine the stratigraphic origin of the skull. Carbonate nodules at the base of the Clarksburg Member and the limestone capping the Birmingham Shale were the most likely sources of the skull based on these analyses, although chemical dissimilarities with the skull matrix existed in both these strata. According to the original describers of Fedexia, the carbonate nodules of the Clarksburg Member were an unlikely source because of biogenic disturbances and an abundance of siliciclastic material.[1]

The holotype skull is 11.5 centimetres (4.5 in) long and is uncrushed and well preserved. Remarkably, the stapes, or middle ear bone, remains intact.[5] Also preserved are both mandibles and the atlas-axis complex, which connects to the base of the skull.[1]

Description

Fedexia possesses several characteristics that identify it as a trematopid. One of the most noticeable is a greatly elongated and subdivided external naris. The posterior portion of the naris may have held a salt gland. Another characteristic is the presence of large palatal tusks. Based on small bony elements present in the related trematopid Anconastes, Fedexia likely had a granular skin texture formed by bony protuberances. These protuberances would have served as protection from predators and would have lessened water loss through the skin.[3]

Unlike other trematopids, Fedexia has a tall, arching lateral profile to the skull. The margin forms a broad arc from the tip of the snout to the occipital region. Other trematopids have a lower, straighter profile to the skull. Another distinguishing feature is that the postorbital length, from the eyes to the back of the skull, is greater than the preorbital length, from the eyes to the tip of the snout. The orbits, or eye sockets, are vertically elongated, extending dorsally to the skull table. There is also a small notch on the premaxilla that separates the premaxillary teeth from the maxillary teeth.[1]

Classification

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic relations of Fedexia, from Berman et al., 2010:[1]

| Temnospondyli |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Like all trematopids, Fedexia was well adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle. Trematopids are the earliest examples of vertebrate life in North America that lived mostly on land, although they likely returned to the water to mate and lay eggs. Fedexia is one of the oldest known vertebrates to have been primarily terrestrial rather than aquatic. Even older are the trematopids Actiobates and Anconastes, which are Missourian (Kasimovian) and early Virgilian in age, respectively.[6][7] The shift toward a terrestrial lifestyle may have been a response to the warmer and drier global climate that existed during the late Carboniferous. During this time, glaciation caused the climate to rapidly fluctuate and sea levels to drop. This resulted in a loss of coal swamps that were once common at higher latitudes. Fedexia was an early example of adaptation to the changing climate. It is possible that terrestrial trematopids existed for a few million years prior to Fedexia, Actiobates, and Anconastes. Earlier trematopids may have inhabited upland regions, and would have later immigrated to lowland and coastal regions as the climate continued to change. Some 20 million years after the appearance of Fedexia, during the Permian period, trematopids and other terrestrial vertebrates experienced rapid diversification.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berman, D.S.; Henrici, A.C.; Brezinski, D.K.; Kollar, A.D. (2010). "A new trematopid amphibian (Temnospondyli: Dissorophoidea) from the Upper Pennsylvanian of western Pennsylvania: earliest record of terrestrial vertebrates responding to a warmer, drier climate" (PDF). Annals of Carnegie Museum. 78 (4): 289–318. doi:10.2992/007.078.0401. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-15.

- ↑ Pitt student finds fossil of ancient amphibian, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 15, 2010

- 1 2 3 Viegas, J. (15 March 2010). "Meat-eating amphibian predated dinos". Discovery News. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Brezinski, D.K. (1983). "Developmental model for an Appalachian Pennsylvanian marine incursion". Northeastern Geology. 5: 92–95.

- 1 2 "Fossil of early terrestrial amphibian discovered". Science Daily. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Eaton, T.H. (1973). "A Pennsylvanian dissorophid amphibian from Kansas". University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Occasional Papers. 14: 1–8.

- ↑ Berman, D.S.; Reisz, R.R.; Eberth, D.A. (1987). "A new genus and species of trematopid amphibian from the Late Pennsylvanian of north-central New Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (3): 252–269. doi:10.1080/02724634.1987.10011659.

External links

- Student Fossil Find Is New Species - CBS News, November 9, 2004