| Laidleria Temporal range: Early Triassic–Middle Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

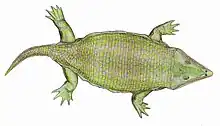

| Laidleria gracilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | Warren, 1998 |

| Genus: | Laidleria Kitching, 1957 |

| Species | |

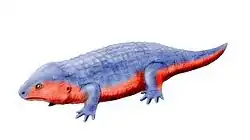

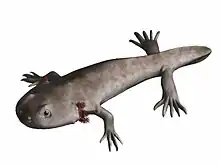

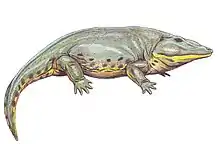

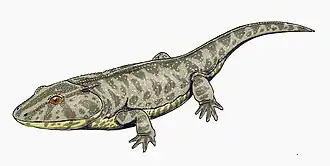

Laidleria is an extinct genus of temnospondyl that likely lived between the Early to Middle Triassic, though its exact stratigraphic range is less certain. Laidleria has been found in the Karoo Basin in South Africa, in Cynognathus Zone A or B.[2][3] The genus is represented by only one species, L. gracilis, though the family Laidleriidae does include other genera, such as Uruyiella, sister taxon to Laidleria, which was discovered and classified in 2007.[4]

Laidleria has been described as being among the smaller temnospondyls, being comparable in size to the smallest of the temnospondyl genera, the bulk of which lived immediately after the Permian-Triassic extinction event.[3] Unlike many other temnospondyls, which were largely aquatic or semi-aquatic, Laidleria likely had a much more terrestrial lifestyle, with its body being covered in dermal armor.[2] However, like other temnospondyls, Laidleria had a sprawling posture.

History and Discovery

Laidleria gracilis was first described in 1957 by Kitching who noticed the fossil in the Albany Museum. From the locality stated on the fossil, the Engcobo District of Eastern Cape Province, as well as the similar lithology of the fossil and its surrounding rock to sandstone found in the Burgersdorp and Lady Frere districts, Kitching placed the fossil as being in the Triassic Cynognathus Zone of the Beaufort Group, Karoo Basin. In his original preparation and description of the fossil, he was able to reveal the palate and occiput of the skull, but was unable to prepare it dorsally, for fear of the skull being not fully intact or that the preparation process could damage the skull due to the hard sandstone around it.[2]

Much debate has surrounded the classification of Laidleria, due to it having a plethora of both derived and plesiomorphic character states.[5] Kitching first called it a trematosaur after much consideration, though he did state that it did have many capitosaurid traits as well.[2] Later, it has been argued that Laidleria should be placed in the superfamily Rhytodosteoidea due to traits such as the placement of the orbitals, short postorbital region, wide occiput, and broad cultriform process.[2][6] Other groups that Laidleria has been attributed to include the family Laidleriidae and the family Rhytidosteidae.[2] Later, in 1998, the specimen was finally able to be prepared dorsally by Warren, which removed much of the taxonomic uncertainty by defining the states of multiple key features, especially those related to the cranial morphology.[2]

Description

Skull

In dorsal view, the skull of Laidleria is triangular, with the edges formed by the premaxillae maxillae, jugals and quadratojugals. The depth of the skull is quite shallow, with the skull looking flattened.[2][7] The quadratojugals have a trough that projects laterally, forming an unusual overhang near the articulation with the quadrate.[2][8][4] Its external nares are located laterally and relatively posteriorly from the anterior edge of the skull, making the prenarial region appear elongated.[2] The orbits are placed near the lateral edges of the skull.[2][6] The septomaxillae and lacrimals may have been absent or very small, though the poor preservation of the bone in this region makes distinguishing this difficult. However, the posterior margin of the skull was preserved quite well, allowing Warren to say with certainty that both the otic notches and otic embayments are not present in the specimen.[2]

Despite the mandibles being preserved in place, obscuring many details in the area, the long parasphenoid-pterygoid contact, the greatly reduced subtemporal vacuities, and the broad cultriform process of the parasphenoid are visible in the palate region. The teeth show incredible variability in size, with small maxillary teeth and larger premaxillary teeth, as well as large tusks on the vomers and palatines. Mandible teeth are notably larger than those on the maxillae, though fewer in number.[2]

Due to the extreme shallowness of the skull, the quadrate condyles are roughly level with the occipital condyles. The occipital condyles, though somewhat difficult to interpret due to imperfections in the preservation of the fossil, appear to be more elliptical in shape than is seen in most temnospondyls, in a way that is characteristic of rhytidosteids. Posttemporal fenestrae are either dramatically reduced or completely absent, resulting also in abbreviated paroccipital processes. The tabular horn and otic notch are both absent, profoundly impacting the morphology of the occipital region, possibly contributing to how reduced this area is. Large stapes are present on both sides of the skull, though they are unique in that they are attached to the skull roof such that they could not have been in contact with a post cranial tympanum.[2]

Post-cranial Skeleton

The vertebral column of Laidleria consists of solid centra, without a marked midline notch, and neural arches with short transverse processes and neural spines. Pleurocentra are barely visible, with only small bony residues that could possibly be the pleurocentra, suggesting that they may have been reduced or cartilaginous.[2] Laidleria has flexible vertebrae better suited to its more terrestrial lifestyle, differing from the ancestral condition of having stiffer vertebrae, as well as spool-like intercentra, which may have contributed to its increased mobility on land as well.[9] Both the dorsal and ventral surfaces of Laidleria are covered in small, ornamented scutes, giving it a unique dermal armor that is uncommon in Temnospondyls.[2][10] Dorsal scutes are larger and less rounded than the scutes located on the ventral surface. Dermal armor of this kind is not typically found in temnospondyls, especially those from the Triassic period, though armored temnospondyls are somewhat more common in the Permian.[2]

Paleobiology

Very little has been found about the paleobiology of Laidleria, though much can be inferred from what is known about other similar genera. Laidleria, being more suited to a terrestrial lifestyle than the bulk of other temnospondyls, would have also eaten terrestrial prey and had a bite suited for such an environment. This may be visible through the irregular emarginations of the dorsal surface of the skull anterior to the external naris, which may have been a result of pressure from dentary tusks, an outcome of greater pressure bites.[2][3] However, the poor preservation of the teeth makes further analysis of their exact diet difficult. Additionally, it is known that Laidleria did have stapes present on the skull, though these structures could not have been connected to a post cranial tympanum.[2] As such, they were likely not used for hearing, with any hearing being likely done through feeling vibrations of the ground.

Paleoenvironment

Laidleria was found in the Karoo Basin in South Africa, namely from the Burgersdorp formation, within hard sandstone deposits characteristic of the Early to Middle Triassic in that region.[2] This period, coming off the end of the Permian-Triassic mass extinction event, was characterized by rapid diversification and massive success of temnospondyls that survived the mass extinction, both within the Karoo Basin and on a more global scale.[3] During the Anisian and Olenekian, Temnospondyl diversity returned to levels comparable to pre-extinction event levels.[3][11] Laidleria doubtless benefitted from the post-extinction event conditions as other temnospondyls did, taking advantage of their more terrestrial lifestyle to expand their range and available resources away from the water sources that more aquatic temnospondyls relied on. However, this genus has not been found outside of South Africa, suggesting that they did not have a terribly large geographic range while they were alive.

See also

References

- ↑ Anne Warren (1998). "Laidleria uncovered: a redescription of Laidleria gracilis Kitching (1957), a temnospondyl from the Cynognathus Zone of South Africa". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 122 (1–2): 167–185. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb02528.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Warren, Anne (1998). "Laidleria uncovered: a redescription of Laidleria gracilis Kitching (1957), a temnospondyl from the Cynognathus Zone of South Africa". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 122 (1–2): 167–185. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb02528.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tarailo, David A (2018). "Taxonomic and ecomorphological diversity of temnospondyl amphibians across the Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin (South Africa)". Journal of Morphology. 279 (12): 1840–1848. doi:10.1002/jmor.20906.

- 1 2 Piñero, Graciela (2007-12-30). "Temnospondyl diversity of the Permian-Triassic Colonia Orozco Local Fauna (Buena Vista Formation) of Uruguay". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 10 (3): 169–180. doi:10.4072/rbp.2007.3.04. ISSN 1519-7530.

- ↑ Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio; Marsicano, Claudia (2011). "Phylogenetic reappraisal of Rhytidosteidae (Stereospondyli: Trematosauria), temnospondyl amphibians from the Permian and Triassic". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 9 (2): 305–325. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.492664. hdl:11336/68471. ISSN 1477-2019.

- 1 2 Cosgriff, J.W.; Zawiskie, J.M. (1979). "A new species of the Rhytidosteidae from the Lystrosaurus zone and a review of the Rhytidosteoidea". Wits Institutional Repository.

- ↑ Schoch, Rainer R. (2013). "The evolution of major temnospondyl clades: an inclusive phylogenetic analysis". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (6): 673–705. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.699006. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ↑ Piñeiro, Graciela; Marsicano, Claudia; Lorenzo, Nora (2007). "A New Temnospondyl from the Permo‐Triassic Buena Vista Formation of Uruguay". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 627–640. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00645.x. hdl:11336/93656. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ↑ Carter, Aja Mia; Hsieh, S. Tonia; Dodson, Peter; Sallan, Lauren (2021-06-09). Langer, Max Cardoso (ed.). "Early amphibians evolved distinct vertebrae for habitat invasions". PLOS ONE. 16 (6): e0251983. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251983. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8189462. PMID 34106947.

- ↑ Thomas., Schoch, Rainer R. Fastnacht, Michael. Fichter, Jürgen. Keller (2007). Anatomy and relationships of the Triassic temnospondyl Sclerothorax. OCLC 999108543.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ruta, Marcello; Benton, Michael J. (2008). "Calibrated Diversity, Tree Topology and the Mother of Mass Extinctions: The Lesson of Temnospondyls". Palaeontology. 51 (6): 1261–1288. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00808.x.