The gladiatrix (pl.: gladiatrices)[1] is the female equivalent of the gladiator of ancient Rome. Like their male counterparts, gladiatrices fought each other, or wild animals, to entertain audiences at various games and festivals. Very little is known about them. They seem to have used much the same equipment as male gladiators, but were heavily outnumbered by them, and were almost certainly considered an exotic rarity by their audiences. They seem to have been introduced during the very Late Republic and early Roman empire, and were officially banned as unseemly from 200 AD onwards. Their existence is known only through a few accounts written by members of Rome's elite, and a very small number of inscriptions.

History

Female gladiators rarely appear in Roman histories. When they do, they are "exotic markers of truly lavish spectacle".[2] In 66 AD, Nero had Ethiopian women, men and children fight at a munus to impress King Tiridates I of Armenia.[3] Romans seem to have found the idea of a female gladiator novel and entertaining, or downright absurd; Juvenal titillates his readers with a woman named "Mevia", a beast-hunter, hunting boars in the arena "with spear in hand and breasts exposed",[4] and Petronius mocks the pretensions of a rich, low-class citizen, whose munus includes a woman fighting from a cart or chariot.[5] A munus circa 89 AD, during Domitian's reign, featured battles between female gladiators, described as "Amazonian".[6]

Training and performance

There is no evidence for the existence or training of female gladiators in any known gladiator school. Vesley suggests that some might have trained under private tutors in Collegia Iuvenum (official "youth organisations"), where young men of over 14 years could learn "manly" skills, including the basic arts of war.[7] He offers three inscriptions as possible evidence; one, from Reate, commemorates Valeria, who died aged seventeen years and nine months and "belonged" to her collegium; the others commemorate females attached to collegia in Numidia and Ficulea.[8] Most modern scholarship describes these as memorials to female servants or slaves of the collegia, not female gladiators.[9][10] Nevertheless, female gladiators probably followed the same training, discipline and career path as their male counterparts;[11][12] though under a less strenuous training regime.[13]

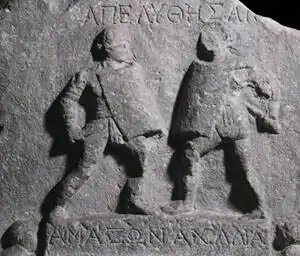

As male gladiators were usually pitted against fighters of similar skill and capacity, the same probably applied to female gladiators.[14] A commemorative marble relief from Halicarnassus shows two near-identical gladiators facing each other. One is identified as Amazonia and the other as Achillia; their warlike "stage names" allude to the mythical tribe of warrior-women, and a feminine version of the warrior-hero Achilles. Otherwise, neither one is recognisable as male or female. Each is bareheaded, equipped with a greave, loincloth, belt, rectangular shield, dagger and manica (arm protection). Two rounded objects at their feet probably represent their discarded helmets.[15] An inscription describes their match as missio, meaning that they were released;[16] the relief, and its inscription, might indicate that they fought to an honourable "standing tie" as equals.[17]

Status and morality

A number of specific legal and moral codes applied to gladiators. In an edict of 22 BC, all men of senatorial class (not including equites) down to their grandsons were prohibited from participating in the games, on penalty of infamia, which involved loss of social status and certain legal rights. In 19 AD, during the reign of Tiberius, this prohibition was extended under the Larinum Decree, to include equites, and women of citizen rank. Henceforth, all arenarii (those who appeared in the arena, in any capacity) could be declared "infames".[18] This would have limited the participation of high-status women in the games, as intended, but would have made no difference to those already defined as infames, such as the low-status (non-citizen) women, freed or slave, who might serve or otherwise assist in the gladiator schools (known as Ludi) and be gladiators' wives, partners or followers (Ludia).[19][20] The terms of the edict indicate a class-based, rather than a gendered prohibition. Roman morality required that all gladiators be of the lowest social classes. Emperors such as Caligula, who failed to respect this distinction, earned the scorn of posterity; Cassius Dio takes pains to point out that when the much admired emperor Titus used female gladiators, they were of acceptably low class.[2]

An inscription at Ostia Antica, marking games held there around the mid 2nd century AD, refers to a local magistrate's generous provision of "women for the sword". This is presumed to mean female gladiators, rather than victims. The inscription defines them as mulieres (women), rather than feminae (ladies), in keeping with their low social status.[21] Juvenal describes high-status women who appear in the games as "rich women who have lost all sense of the dignities and duties of their sex."[22] Their self-indulgence was held to have brought shame upon themselves, their gender, and Rome's social order;[23] they, or their sponsors, undermined traditional Roman virtues and values.[23] Women beast-hunters (bestiarii) could earn praise and a good reputation for courage and skill; Martial describes one who killed a lion - a Herculean feat, which reflected well on her editor, the emperor Titus; but Juvenal was less than impressed by Mevia, who hunted boars with a spear "like a man."[11]

Some regarded female gladiators of any class as a symptom of corrupted Roman sensibilities, morals and womanhood. Before he became emperor, Septimius Severus may have attended the Antiochene Olympic Games, which had been revived by the emperor Commodus and included traditional Greek female athletics. Septimius' attempt to give Romans a similarly dignified display of female athletics was met by the crowd with ribald chants and cat-calls.[24] Probably as a result, he banned the use of female gladiators, from 200 AD.[25]

There may have been more, and earlier female gladiators than the sparse evidence allows; McCullough speculates the unremarked introduction of lower-class gladiatores mulieres at some time during the Augustan era, when the gift of luxurious, crowd-pleasing games and abundant novelty became an exclusive privilege of the state, provided by the emperor or his officials. On the whole, Rome's elite authorities exhibit indifference to the existence and activities of non-citizen arenari of either gender. The Larinum decree made no mention of lower-class mulieres, so their use as gladiators was permissible. Septimius Severus' later wholesale ban on female gladiators may have been selective in its practical application, targeting higher-status women with personal and family reputations to lose. Nevertheless, this does not imply low-class female gladiators were commonplace in Roman life. Male gladiators were wildly popular, and were celebrated in art, and in countless images across the Empire. Only one near-certain image of female gladiators survives; their appearance in Roman histories is extremely rare, and is invariably described by observers as unusual, exotic, aberrant or bizarre. Brunet remarks that the Romans had no specific word for female gladiators as type or class.[26] This seems the case during the Classical era. The earliest reference to a woman gladiator as gladiatrix is post-classical, made in the 4th or 5th century by a scoliast on Juvenal, Satire 6, 250-251, where Juvenal mockingly asks if a woman under training in a ludus is preparing for the Floralia (the festival of Flora) or "if she plans something more in that mind, and is preparing for the real arena"/nam vere vult esse gladiatrix quae meretrix (“for truly she wants to be a gladiatrix who is a prostitute”).[27][28]

Burials

Most gladiators paid subscriptions to "burial clubs" that ensured their proper burial on death, in segregated cemeteries reserved for their class and profession. A cremation burial unearthed in Southwark, London in 2001 was identified by some sources as that of a possible female gladiator (named the Great Dover Street woman). She was buried outside the main cemetery, along with pottery lamps of Anubis (who like Mercury, would lead her into the afterlife), a lamp with the image of a fallen gladiator, and the burnt remnants of Stone Pine cones, whose fragrant smoke was used to cleanse the arena. Her identification as gladiatrix has been variously described as "70 percent probable", "intriguing", "circumstantial", and "erroneous". She may have simply been an enthusiast, or a gladiator's ludia (wife or lover).[16] Human female remains found during an archaeological rescue dig at Credenhill in Herefordshire have also been speculated in the popular media as those of a female gladiator.[29]

Modern depictions

- In Eugene Sue's 1848 novel The Iron Collar (part of Sue's Mysteries of the People) two female gladiators, Symora and Faustina, fight to the death in a Gallic amphitheatre.

- In Cecil B. DeMille's 1932 The Sign of the Cross women are pitted against dwarfs costumed as African pygmies.[30]

- In Gladiator, during a dramatisation of the Battle of Zama, female archers and charioteers enact the role of Scipio Africanus's legions.[31]

In Renaissance art

Among the pictures commissioned in Italy by King Philip IV of Spain for his Palacio del Buen Retiro in Madrid, there is a series on Roman circuses including a duel between two female gladiators.[32]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The singular dates to a 4th/5th century AD scoliast's reference to line 251 in Juvenal. The plural is modern. See McCullough, Anna, "Female Gladiators in the Roman Empire", in: Budin & Turfa (eds), Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, Routledge (2016), p. 958

- 1 2 Futrell 2006, pp. 153–156.

- ↑ Wiedemann 1992, p. 112; Jacobelli 2003, p. 17, citing Cassius Dio, 62.3.1. (or 63.3.1 depending on the edition)

- ↑ Jacobelli 2003, p. 17, citing Juvenal's Saturae, 1.22–1.23.

- ↑ Jacobelli 2003, p. 18, citing Petronius's Satyricon, 45.7.

- ↑ Jacobelli 2003, p. 18, citing Dio Cassius 67.8.4, Suetonius's Domitianus 4.2, and Statius's Silvae 1.8.51–1.8.56. Brunet (2014) p.480, interprets this as "a serious affair and intended to provoke amazement that women could take on the role of men, the only precedent for which derived from the mythical Amazons."

- ↑ Vesley (1998), p. 87

- ↑ Vesley (1998), p. 88

- ↑ Vesley (1998), p. 91

- ↑ Vesley (1998), p. 89

- 1 2 Brunet (2014), p. 484

- ↑ Potter 2010, p. 408

- ↑ Meijer (2005), p. 77

- ↑ Brunet (2014), p. 481

- ↑ Manas (2011), p. 2735

- 1 2 Manas (2011), p. 2734

- ↑ Jacobelli 2003, p. 18; Potter 2010, p. 408.

- ↑ Smith, William. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray, 1875, "Roman Law – Infamia".

- ↑ Jacobelli, L. (2003). Gladiators at Pompeii. Los Angeles, California: J. Paul Getty Museum, 19.

- ↑ McCullough (2008), p. 199

- ↑ Brunet (2014), p. 483

- ↑ McCullough (2008)

- 1 2 McCullough (2008), p. 205

- ↑ Potter 2010, p. 407.

- ↑ Jacobelli 2003, p. 18, citing Dio Cassius 75.16.

- ↑ Brunet (2014), pp. 485–486

- ↑ Coleman (2000), pp. 487–488 for missio and the Halicarnassus relief

- ↑ McCullough, Anna, “Female Gladiators in the Roman Empire”, in: Budin & Turfa (eds), Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, Routledge (2016), p. 958, citing Scholia in Iuvenalem Vetustiora, on Juvenal, Satire 6, 250-251

- ↑ "Female 'gladiator' remains found in Herefordshire". BBC News. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Brunet (2014), p. 478

- ↑ Franzoni, D. (Producer), & Scott, R. (Director). (2000). Gladiator [Motion picture]. United States: DreamWorks Pictures.

- ↑ Women gladiators, Prado collection] (accessed 18 December 2020)

References

- Brunet, Stephen (2014). "Women with swords: female gladiators in the Roman world". In Paul Christesen; Donald G. Kyle (eds.). A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 478–491. doi:10.1002/9781118609965. ISBN 9781444339529.

- Coleman, Kathleen (2000). "Missio at Halicarnassus". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 100: 487–500. doi:10.2307/3185234. JSTOR 3185234.

- Fagan, Garrett G. (2015). "Training Gladiators: Life in the Ludus". In L. L. Brice; D. Slootjes (eds.). Impact of Empire : Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476. Aspects of Ancient Institutions and Geography. Vol. 19. Leiden: Brill. pp. 122–144. doi:10.1163/9789004283725_009. ISBN 9789004283725.

- Jacobelli, Luciana (2003). Gladiators at Pompeii. Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications. ISBN 0-89236-731-8.

- Futrell, Alison (2006). A Sourcebook on the Roman Games. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1568-8.

- Manas, Alfonso (2011). "New evidence of female gladiators: the bronze statuette at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe of Hamburg". International Journal of the History of Sport. 28 (18): 2726–2752. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.618267. S2CID 145273035.

- McCullough, A. (2008). "Female gladiators in imperial Rome: literary context and historical fact". The Classical World. 101 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1353/clw.2008.0000. JSTOR 25471938. S2CID 161800922.

- McCullough, Anna, “Female Gladiators in the Roman Empire”, in: Budin & Turfa (eds), Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, Routledge, 2016

- Meijer, Fik (2005). The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport. Translated by L. Waters. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780312364021.

- Murray, Steven (2003). "Female gladiators of the ancient Roman world". Journal of Combative Sport.

- Potter, David Stone (2010). A Companion to the Roman Empire. West Sussex, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Limited (John Wiley and Sons). ISBN 978-1-4051-9918-6.

- Vesley, Mark E. (1998). "Gladiatorial training for girls in the Collegia Iuvenum of the Roman Empire". Échos du Monde Classique. 62 (17): 85–93.

- Wiedemann, Thomas (1992). Emperors and Gladiators. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12164-7.

External links

- Journal of Combative Sport 2003

- "Is the term "gladiatrix" modern?" 2020

- Part of the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (ThLL), published in print in Leipzig et al, 1900. See end of "Gladiator" entry for gladiatrix: