In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες Amazónes, singular Ἀμαζών Amazōn; in Latin Amāzon, -ŏnis) are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Heracles, the Argonautica and the Iliad. They were a group of female warriors and hunters, who were as skilled and courageous as men in physical agility, strength, archery, riding skills, and the arts of combat. Their society was closed to men and they only raised their daughters and returned their sons to their fathers, with whom they would only socialize briefly in order to reproduce.[1][2]

Courageous and fiercely independent, the Amazons, commanded by their queen, regularly undertook extensive military expeditions into the far corners of the world, from Scythia to Thrace, Asia Minor and the Aegean Islands, reaching as far as Arabia and Egypt.[3] Besides military raids, the Amazons are also associated with the foundation of temples and the establishment of numerous ancient cities like Ephesos, Cyme, Smyrna, Sinope, Myrina, Magnesia, Pygela, etc.[4][5]

The texts of the original myths envisioned the homeland of the Amazons at the periphery of the then-known world. Various claims to the exact place ranged from provinces in Asia Minor (Lycia, Caria, etc.) to the steppes around the Black Sea, or even Libya (Libyan Amazon). However, authors most frequently referred to Pontus in northern Anatolia, on the southern shores of the Black Sea, as the independent Amazon kingdom where the Amazon queen resided at her capital Themiscyra, on the banks of the Thermodon river.[6]

Palaephatus, who himself might have been a fictional character, attempted to rationalize the Greek myths in his work On Unbelievable Tales. He suspected that the Amazons were probably men who were mistaken for women by their enemies because they wore clothing that reached their feet, tied up their hair in headbands, and shaved their beards. Probably the first in a long line of skeptics, he rejected any real basis for them, reasoning that because they did not exist during his time, most probably they did not exist in the past either.[7][8][9]

Decades of archaeological discoveries of burial sites of female warriors, including royalty, in the Eurasian Steppes suggest that the horse cultures of the Scythian, Sarmatian and Hittite peoples likely inspired the Amazon myth.[10][11] In 2019, a grave with multiple generations of female Scythian warriors, armed and in golden headdresses, was found near Russia's Voronezh.[12]

Name

Etymology

The origin of the word is uncertain.[13] It may be derived from an Iranian ethnonym *ha-mazan- 'warriors', a word attested indirectly through a derivation, a denominal verb in Hesychius of Alexandria's gloss "ἁμαζακάραν· πολεμεῖν. Πέρσαι" ("hamazakaran: 'to make war' in Persian"), where it appears together with the Indo-Iranian root *kar- 'make'.[13]

It may alternatively be a Greek word descended from *n̥-mn̥gʷ-yō-nós 'manless, without husbands' (alpha privative combined with a derivation from *man- cognate with Proto-Balto-Slavic *mangjá-, found in Czech muž) has been proposed, an explanation deemed "unlikely" by Hjalmar Frisk. A further explanation proposes Iranian *ama-janah 'virility-killing' as source.[14]

Among the ancient Greeks, the term Amazon was popularly folk etymologized as originating from the Greek ἀμαζός, amazos ('breastless'), from -a ('without') and mazos, a variant of mastos ('breast'),[15] connected with an etiological tradition once claimed by Marcus Justinus who alleged that Amazons had their right breast cut off or burnt out.[16] There is no indication of such a practice in ancient works of art,[17] in which the Amazons are always represented with both breasts, although one is frequently covered.[18] According to Philostratus Amazon babies were not fed just with the right breast.[19] Author Adrienne Mayor suggests that the false etymology led to the myth.[17][20]

Alternative terms

Herodotus used the terms Androktones (Ἀνδροκτόνες) 'killers/slayers of men' or 'of husbands' and Androleteirai (Ἀνδρολέτειραι) 'destroyers of men, murderesses'. Amazons are called Antianeirai (Ἀντιάνειραι) 'equivalent to men' and Aeschylus used the term Styganor (Στυγάνωρ) 'those who loathe all men'.[21]

In his work Prometheus Bound and in The Suppliants, Aeschylus referred to the Amazons as 'the unwed, flesh-devouring Amazons' (...τὰς ἀνάνδρους κρεοβόρους τ᾽ Ἀμαζόνας). In the Hippolytus tragedy, Phaedra calls Hippolytus, 'the son of the horse-loving Amazon' (...τῆς φιλίππου παῖς Ἀμαζόνος βοᾷ Ἱππόλυτος...). In his Dionysiaca, Nonnus calls the Amazons of Dionysus Androphonus (Ἀνδροφόνους) 'men slaying'.[22][23] Herodotus stated that in the Scythian language, the Amazons were called Oiorpata, which he explained as being from oior 'man' and pata 'to slay'.

Historiography

The ancient Greeks never had any doubts that the Amazons were, or had been, real. Not the only people enchanted by warlike women of nomadic cultures, such exciting tales also come from ancient Egypt, Persia, India, and China. Greek heroes of old had encounters with the queens of their martial society and fought them. However, their original home was not exactly known, thought to be in the obscure lands beyond the civilized world.[24] As a result, for centuries scholars believed the Amazons to be purely imaginary, although there were various proposals for a historical nucleus of the Amazons in Greek historiography. Some authors preferred comparisons to cultures of Asia Minor or even Minoan Crete. The most obvious historical candidates are Lycia and Scythia and Sarmatia in line with the account by Herodotus. In his Histories (5th century BC) Herodotus claims that the Sauromatae (predecessors of the Sarmatians), who ruled the lands between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, arose from a union of Scythians and Amazons.[25]

Herodotus also observed rather unusual customs among the Lycians of southwest Asia Minor. The Lycians obviously followed matrilineal rules of descent, virtue, and status. They named themselves along their maternal family line and a child's status was determined by the mother's reputation. This remarkably high esteem of women and legal regulations based on maternal lines, still in effect in the 5th century BC in the Lycian regions that Herodotus had traveled to, lent him the idea that these people were descendants of the mythical Amazons.[26]

Modern historiography no longer relies exclusively on textual and artistic material, but also on the vast archaeological evidence of over a thousand nomad graves from steppe territories from the Black Sea all the way to Mongolia. Discoveries of battle-scarred female skeletons buried with their weapons (bows and arrows, quivers, and spears) prove that women warriors were not merely figments of imagination, but the product of the Scythian/Sarmatian horse-centered lifestyle.[27][28]

Mythology

According to myth, Otrera, the first Amazon queen, is the offspring of a romance between Ares the god of war and the nymph Harmonia of the Akmonian Wood, and as such a demigoddess.[29][30][31]

Early records refer to two events in which Amazons appeared prior to the Trojan War (before 1250 BC). Within the epic context, Bellerophon, Greek hero, and grandfather of the brothers and Trojan War veterans Glaukos and Sarpedon, faced Amazons during his stay in Lycia, when King Iobates sent Bellerophon to fight the Amazons, hoping they would kill him, yet Bellerophon slew them all. The youthful King Priam of Troy fought on the side of the Phrygians, who were attacked by Amazons at the Sangarios River.[32]

Amazons in the Trojan War

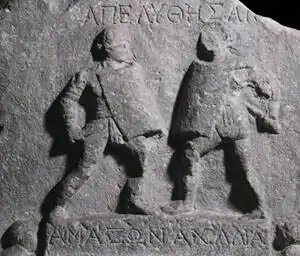

There are Amazon characters in Homer's Trojan War epic poem, the Iliad, one of the oldest surviving texts in Europe (around 8th century BC). The now lost epic Aethiopis (probably by Arctinus of Miletus, 6th century BC), like the Iliad and several other epics, is one of the works that in combination form the Trojan War Epic Cycle. In one of the few references to the text, an Amazon force under queen Penthesilea, who was of Thracian birth, came to join the ranks of the Trojans after Hector's death and initially put the Greeks under serious pressure. Only after the greatest effort and the help of the reinvigorated hero Achilles, the Greeks eventually triumphed. Penthesilea died fighting the mighty Achilles in single combat.[33] Homer himself deemed the Amazon myths to be common knowledge all over Greece, which suggests that they had already been known for some time before him. He was also convinced that the Amazons lived not at its fringes, but somewhere in or around Lycia in Asia Minor - a place well within the Greek world.

Troy is mentioned in the Iliad as the place of Myrine's death.[34][35] Later identified as an Amazon queen, according to Diodorus (1st century BC), the Amazons under her rule invaded the territories of the Atlantians, defeated the army of the Atlantian city of Cerne, and razed the city to the ground.[36][18]

In Scythia

The Poet Bacchylides (6th century BC) and the historian Herodotus (5th century BC) located the Amazon homeland in Pontus at the southern shores of the Black Sea, and the capital Themiscyra at the banks of the Thermodon (modern Terme river), by the modern city of Terme. Herodotus also explains how it came to be that some Amazons would eventually be living in Scythia. A Greek fleet, sailing home upon defeating the Amazons in battle at the Thermodon river, included three ships crowded with Amazon prisoners. Once out at sea, the Amazon prisoners overwhelmed and killed the small crews of the prisoner ships and, despite not having even basic navigation skills, managed to escape and safely disembark at the Scythian shore. As soon as the Amazons had caught enough horses, they easily asserted themselves in the steppe in between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea and, according to Herodotus, would eventually assimilate with the Scythians, whose descendants were the Sauromatae, the predecessors of the Sarmatians.[37][2]

Amazon homeland

Strabo (1st century BC) visits and confirms the original homeland of the Amazons on the plains by the Thermodon river. However, long gone and not seen again during his lifetime, the Amazons had allegedly retreated into the mountains. Strabo, however, added that other authors, among them Metrodorus of Scepsis and Hypsicrates claim that after abandoning Themiscyra, the Amazons had chosen to resettle beyond the borders of the Gargareans, an all-male tribe native to the northern foothills of the Caucasian Mountains. The Amazons and Gargareans had for many generations met in secrecy once a year during two months in spring, in order to produce children. These encounters would take place in accordance with ancient tribal customs and collective offers of sacrifices. All females were retained by the Amazons themselves, and males were returned to the Gargareans.[38] 5th century BC poet Magnes sings of the bravery of the Lydians in a cavalry-battle against the Amazons.[39][40][41]

Heracles myth

Hippolyte was an Amazon queen killed by Heracles, who had set out to obtain the queen's magic belt in a task he was to accomplish as one of the Labours of Heracles. Although neither side had intended to resort to lethal combat, a misunderstanding led to the fight. In the course of this, Heracles killed the queen and several other Amazons. In awe of the strong hero, the Amazons eventually handed the belt to Heracles. In another version, Heracles does not kill the queen, but exchanges her kidnapped sister Melanippe for the belt.[42][13][43][41]

Theseus myth

Queen Hippolyte was abducted by Theseus, who took her to Athens, where she experienced forced marriage, sexual slavery, rape, and- as a result of forced pregnancy- bore him a son, Hippolytus. In other versions, the kidnapped Amazon is called Antiope, the sister of Hippolyte. In revenge, the Amazons invaded Greece, plundered some cities along the coast of Attica, and besieged and occupied Athens. Hippolyte, who fought on the side of Athens, according to another account was killed during the final battle along with all of the Amazons.[43][44]

Amazons and Dionysus

According to Plutarch, the god Dionysus and his companions fought Amazons at Ephesus. The Amazons fled to Samos and Dionysus pursued them and killed a great number of them at a site since called Panaema (blood-soaked field).[45] The Christian author Eusebius writes that during the reign of Oxyntes, one of the mythical kings of Athens, the Amazons burned down the temple at Ephesus.[46]

In another myth Dionysus unites with the Amazons to fight against Cronus and the Titans. Polyaenus writes that after Dionysus has subdued the Indians, he allies with them and the Amazons and takes them into his service, who serve him in his campaign against the Bactrians. Nonnus in his Dionysiaca reports about the Amazons of Dionysus, but states that they do not come from Thermodon.[22][47]

Amazons and Alexander the Great

Amazons are also mentioned by biographers of Alexander the Great, who report of Queen Thalestris bearing him a child (a story in the Alexander Romance).[48] However, other biographers of Alexander dispute the claim, including the highly regarded Plutarch. He noted a moment when Alexander's naval commander Onesicritus read an Amazon myth passage of his Alexander History to King Lysimachus of Thrace who had taken part in the original expedition. The king smiled at him and said: "And where was I, then?"[49]

The Talmud[50] recounts that Alexander wanted to conquer a "kingdom of women" but reconsidered when the women told him:

If you kill us, people will say: Alexander kills women; and if we kill you, people will say: Alexander is the king whom women killed in battle.

Roman and ancient Egyptian records

Virgil's characterization of the Volsci warrior maiden Camilla in the Aeneid borrows from the myths of the Amazons. Philostratus, in Heroica, writes that the Mysian women fought on horses alongside the men, just as the Amazons. The leader was Hiera, wife of Telephus. The Amazons are also said to have undertaken an expedition against the Island of Leuke, at the mouth of the Danube, where the ashes of Achilles were deposited by Thetis. The ghost of the dead hero so terrified the horses, that they threw off and trampled upon the invaders, who were forced to retreat.[18] Virgil touches on the Amazons and their queen Penthesilea in his epic Aeneid (around 20 BC).

The biographer Suetonius had Julius Caesar remark in his De vita Caesarum that the Amazons once ruled a large part of Asia. Appian provides a vivid description of Themiscyra and its fortifications in his account of Lucius Licinius Lucullus' Siege of Themiscyra in 71 BC during the Third Mithridatic War.[51][52][42]

An Amazon myth has been partly preserved in two badly fragmented versions around historical people in 7th century BC Egypt. The Egyptian prince Petechonsis and allied Assyrian troops undertook a joint campaign into the Land of Women, to the Middle East at the border to India. Petechonsis initially fought the Amazons, but soon fell in love with their queen Sarpot and eventually allied with her against an invading Indian army. This story is said to have originated in Egypt independently of Greek influences.[53][54]

Amazon queens

.jpg.webp)

Sources provide names of individual Amazons, that are referred to as queens of their people, even as the head of a dynasty. Without a male companion, they are portrayed in command of their female warriors. Among the most prominent Amazon queens were:

- Otrera, daughter of the nymph Harmonia and god of war, Ares. She is the mother of Hippolyta, Antiope, Melanippe, and Penthesilea and the mythical founder of the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

- Hippolyta, daughter of Otrera and Ares. She is part of the Theseus and Heracles myths, in which Antiope is her sister. Alcippe, the only Amazon known to have sworn a chastity oath, belongs to her entourage.

- Penthesilea, who kills her sister Hippolyte in a hunting accident, comes to the aid of the hard-pressed Trojans with her warriors, is defeated by Achilles, who mourns her.

- Lampedo and Marpesia, queens of the Amazons mentioned by Justin

- Myrina, who leads a military expedition in Libya, defeats the Atlanteans, forms an alliance with the ruler of Egypt, and conquers numerous cities and islands.

- Thalestris, the last known Amazon queen. According to legend, she meets the Greek conqueror Alexander the Great in 330 BC. Her home is the Thermodon region, or, variably, the Gates of Alexander, south of the Caspian Sea.

Various authors and chroniclers

Quintus Smyrnaeus

Quintus Smyrnaeus, author of the Posthomerica lists the attendant warriors of Penthesilea: "Clonie was there, Polemusa, Derinoe, Evandre, and Antandre, and Bremusa, Hippothoe, dark-eyed Harmothoe, Alcibie, Derimacheia, Antibrote, and Thermodosa glorying with the spear."[55]

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus lists twelve Amazons who challenged and died fighting Heracles during his quest for Hippolyta's girdle: Aella, Philippis, Prothoe, Eriboea, Celaeno, Eurybia, Phoebe, Deianeira, Asteria, Marpe, Tecmessa, and Alcippe. After Alcippe's death, a group attack followed. Diodorus also mentions Melanippe, whom Heracles set free after accepting her girdle and Antiope as ransom.[56]

Diodorus lists another group with Myrina as the queen who commanded the Amazons in a military expedition in Libya, as well as her sister Mytilene, after whom she named the city of the same name. Myrina also named three more cities after the Amazons who held the most important commands under her, Cyme, Pitane, and Priene.

Justin and Paulus Orosius

Both Justin in his Epitome of Trogus Pompeius and Paulus Orosius give an account of the Amazons, citing the same names. Queens Marpesia and Lampedo shared the power during an incursion in Europe and Asia, where they were slain. Marpesia's daughter Orithyia succeeded them and was greatly admired for her skill on war. She shared power with her sister Antiope, but she was engaged in war abroad when Heracles attacked. Two of Antiope's sisters were taken prisoner, Melanippe by Heracles and Hippolyta by Theseus. Heracles latter restored Melanippe to her sister after receiving the queen's arms in exchange, though, on other accounts she was killed by Telamon. They also mention Penthesilea's role in the Trojan War.[57][58][59]

Hyginus

Another list of Amazons' names is found in Hyginus' Fabulae. Along with Hippolyta, Otrera, Antiope and Penthesilea, it attests the following names: Ocyale, Dioxippe, Iphinome, Xanthe, Hippothoe, Laomache, Glauce, Agave, Theseis, Clymene, Polydora.[60]

Perhaps the most important is Queen Otrera, consort of Ares and mother by him of Hippolyta and Penthesilea.[61] She is also known for building a temple to Artemis at Ephesus.[62]

Valerius Flaccus

Another different set of names is found in Valerius Flaccus' Argonautica. He mentions Euryale, Harpe, Lyce, Menippe and Thoe. Of these Lyce also appears on a fragment, preserved in the Latin Anthology where she is said to have killed the hero Clonus of Moesia, son of Doryclus, with her javelin.[63]

Late Antiquity, Middle Age and Renaissance literature

Stephanus of Byzantium (7th-century CE) provides numerous alternative lists of the Amazons, including for those who died in combat against Heracles, describing them as the most prominent of their people. Both Stephanus and Eustathius connect these Amazons with the placename Thibais, which they claim to have been derived from the Amazon Thiba's name.[64] Several of Stephanus' Amazons served as eponyms for cities in Asia Minor, like Cyme and Smyrna or Amastris, who was believed to lend her name to the city previously known as Kromna, although in fact it was named after the historical Amastris. The city Anaea in Caria was named after an Amazon.[65][66]

In his work Getica (on the origin and history of the Goths, c. 551 CE) Jordanes asserts that the Goths' ancestors, descendants of Magog, originally lived in Scythia, at the Sea of Azov between the Dnieper and Don Rivers. When the Goths were abroad campaigning against Pharaoh Vesosis, their women, on their own successfully fended off a raid by a neighboring tribe. Emboldened, the women established their own army under Marpesia, crossed the Don and invaded eastward into Asia. Marpesia's sister Lampedo remained in Europe to guard the homeland. They procreated with men once a year. These women conquered Armenia, Syria and all of Asia Minor, even reaching Ionia and Aeolis, holding this vast territory for 100 years.

In Digenes Akritas, the twelfth century medieval epic of Basil, the Greco-Syrian knight of the Byzantine frontier, the hero battles and then commits adultery with the female warrior Maximo (killing her afterwards in one version of the epic), descended from some Amazons and taken by Alexander from the Brahmans.[67][68]

John Tzetzes lists in Posthomerica twenty Amazons, who fell at Troy. This list is unique in its attestation for all the names but Antianeira, Andromache and Hippothoe. Other than these three, the remaining 17 Amazons were named as Toxophone, Toxoanassa, Gortyessa, Iodoce, Pharetre, Andro, Ioxeia, Oistrophe, Androdaixa, Aspidocharme, Enchesimargos, Cnemis, Thorece, Chalcaor, Eurylophe, Hecate, and Anchimache.[69]

Famous medieval traveller John Mandeville mentions them in his book:

Beside the land of Chaldea is the land of Amazonia, that is the land of Feminye. And in that realm is all woman and no man; not as some may say, that men may not live there, but for because that the women will not suffer no men amongst them to be their sovereigns.[70]

Medieval and Renaissance authors credit the Amazons with the invention of the battle-axe. This is probably related to the sagaris, an axe-like weapon associated with both Amazons and Scythian tribes by Greek authors (see also Thracian tomb of Aleksandrovo kurgan). Paulus Hector Mair expresses astonishment that such a "manly weapon" should have been invented by a "tribe of women", but he accepts the attribution out of respect for his authority, Johannes Aventinus.

Ariosto's Orlando Furioso contains a country of warrior women, ruled by Queen Orontea; the epic describes an origin much like that in Greek myth, in that the women, abandoned by a band of warriors and unfaithful lovers, rallied together to form a nation from which men were severely reduced, to prevent them from regaining power. The Amazons and Queen Hippolyta are also referenced in Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales in "The Knight's Tale".

Amazons continued to be subject of scholarly debate during the European Renaissance, and with the onset of the Age of Exploration, encounters were reported from ever more distant lands. In 1542, Francisco de Orellana reached the Amazon River, naming it after the Icamiabas,[71] a tribe of warlike women he claimed to have encountered and fought on the Nhamundá River, a tributary of the Amazon.[72][73][74] Afterwards the whole basin and region of the Amazon (Amazônia in Portuguese, Amazonía in Spanish) were named after the river. Amazons also figure in the accounts of both Christopher Columbus and Walter Raleigh.[75]

Amazons in art

Beginning around 550 BC. depictions of Amazons as daring fighters and equestrian warriors appeared on vases. After the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC the Amazon battle - Amazonomachy became popular motifs on pottery. By the sixth century BC, public and privately displayed artwork used the Amazon imagery for pediment reliefs, sarcophagi, mosaics, pottery, jewelry and even monumental sculptures, that adorned important buildings like the Parthenon in Athens. Amazon motifs remained popular until the Roman imperial period and into Late antiquity.[76]

Apart from the artistic desire to express the passionate womanhood of the Amazons in contrast with the manhood of their enemies, some modern historians interpret the popularity of Amazon in art as indicators of societal trends, both positive and negative. Greek and Roman societies, however, utilized the Amazon mythology as a literary and artistic vehicle to unite against a commonly-held enemy. The metaphysical characteristics of Amazons were seen as personifications of both nature and religion. Roman authors like Virgil, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, Curtius, Plutarch, Arrian, and Pausanius advocated the greatness of the state, as Amazon myths served to discuss the creation of origin and identity for the Roman people. However, that changed over time. Amazons in Roman literature and art have many faces, such as the Trojan ally, the warrior goddess, the native Latin, the warmongering Celt, the proud Sarmatian, the hedonistic and passionate Thracian warrior queen, the subdued Asian city, and the worthy Roman foe.[77][78][79]

In Renaissance Europe, artists started to reevaluate and depict Amazons based on Christian ethics. Queen Elizabeth of England was associated with Amazon warrior qualities (the foremost ancient examples of feminism) during her reign and was indeed depicted as such. Though, as explained in Divina Virago by Winfried Schleiner, Celeste T. Wright has given a detailed account of the bad reputation Amazons had in the Renaissance. She notes that she has not found any Elizabethans comparing the Queen to an Amazon and suggests that they might have hesitated to do so because of the association of Amazons with enfranchisement of women, which was considered contemptible.[80] Elizabeth was present at a tournament celebrating the marriage of the Earl of Warwick and Anne Russell at Westminster Palace on 11 November 1565 involving male riders dressed as Amazons. They accompanied the challengers carrying their heraldry. These riders wore crimson gowns, masks with long hair attached, and swords.[81]

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel depicted the Battle of the Amazons around 1598, a most dramatic baroque painting, followed by a painting of the Rococo period by Johann Georg Platzer, also titled Battle of the Amazons. In 19th-century European Romanticism German artist Anselm Feuerbach occupied himself with the Amazons as well. His paintings engendered all the aspirations of the Romantics: their desire to transcend the boundaries of the ego and of the known world; their interest in the occult in nature and in the soul; their search for a national identity, and the ensuing search for the mythic origins of the Germanic nation; finally, their wish to escape the harsh realities of the present through immersion in an idealized past.[82]

Archaeology

Speculation that the idea of Amazons contains a core of reality is based on archaeological discoveries at kurgan burial sites in the steppes of southern Ukraine and Russia. The varied war weapons artifacts found in graves of numerous high-ranking Scythian and Sarmatian warrior women have led scholars to conclude that the Amazonian legend has been inspired by the real world: About 20% of the warrior graves on the lower Don and lower Volga contained women dressed for battle similar to how men dress. Armed women accounted for up to 25% of Sarmatian military burials. Russian archaeologist Vera Kovalevskaya asserts that when Scythian men were abroad fighting or hunting, women would have to be able to competently defend themselves, their animals, and their pastures.[83]

In early 20th century Minoan archeology a theory regarding Amazon origins in Minoan civilization was raised in an essay by Lewis Richard Farnell and John Myres. According to Myres, the tradition interpreted in the light of evidence furnished by supposed Amazon cults seems to have been very similar and may have even originated in Minoan culture.[84]

Modern legacy

The city of Samsun in modern-day Samsun Province, Turkey features an Amazon Village museum, to help bring attention to the legacy of the Amazons and to promote both academic interest and tourism. An annual Amazon Celebration Festival takes place in the Terme district.[85][86]

During the Ottoman–Egyptian invasion of Mani in 1826, in the battle of Diros the women of Mani defeated the Ottoman army and for this were given the name of 'The Amazons of Diros'.[87]

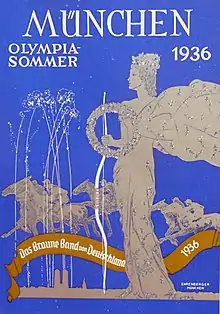

From 1936 to 1939, annual propaganda events, called Night of the Amazons (Nacht der Amazonen) were performed in Nazi Germany at the Nymphenburg Palace Park in Munich.[88] Announced as evening highlights of the International Horse Racing Week Munich-Riem, bare-breasted variety show girls of the SS-Cavalry, 2,500 participants and international guests performed at the open-air revue. These revues served to promote an allegedly emancipated female role and a cosmopolitan and foreigner-friendly Nazi regime.

In literature and media

Literature

- Amazon Queen Hippolyta appears in William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream and also in The Two Noble Kinsmen, which Shakespeare co-wrote with John Fletcher.

- The Amazon queen Penthesilea, and her sexual frenzy, are at the center of the drama Penthesilea by Heinrich von Kleist in 1808.

- Steven Pressfield's 2002 novel Last of the Amazons is a mythopoeia of Plutarch's texts, that surround Theseus' abduction of Queen Antiope and the Amazons' attack on Athens. An accurate and detailed portrayal of the Archaic Greek world, its life, people, weapons etc. dramatized as real as the sky.[89]

- William Moulton Marston, alongside his wife and their lover Olive Byrne, created their rendition of the mythical Amazons, whose members included the superheroine Wonder Woman, for DC Comics. Marston's Amazons are noteworthy for not just being physically superior to mortal men but also technologically superior, being able to create healing rays and undetectable jet planes that can be controlled through brain waves alone, although this element of Amazon society is applied inconsistently in appearances written after Marston's death.[90]

- In Rick Riordan's The Heroes of Olympus, the Amazons appear in The Son of Neptune and The Blood of Olympus. They are the founders and owners of the Amazon corporation.

- In Philip Armstrong's historical-fantasy series, The Chronicles of Tupiluliuma, the Amazons appear as the Am'azzi.

- In the Stieg Larsson novel The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets' Nest, the Amazons appear as the transitional topics between sections of the book.

- Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo created the fictional queen Calafia, who ruled over a kingdom of black women, living in the style of Amazons, on the mythical Island of California.

- Amazon Gazonga is a short comic series created by the Waltrip brothers in 1995. The comic centres around on a young amazon named Gazonga living in the Amazon rainforest.

- GastroPhobia is a webcomic by Daisy McGuire, about the adventures of an exiled Amazon warrior and her son living in Ancient Greece, roughly 3408 years ago.

Film and television

- Franchises involving several Tarzan releases, that have featured Amazon tribes (Tarzan and the Amazons, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle)

- In the animated series The Mysterious Cities of Gold, a tribe of Amazons appeared in two episodes.

- Frank Hart, portraying a misogynist, is kidnapped by Amazons in the 1980 film 9 to 5.[91]

- Amazons appear in the movies The Loves of Hercules (1960), Battle of the Amazons (1970), War Goddess (1973), Hundra (1983), Amazons (1986), Deathstalker II (1987), Ronal the Barbarian (2011), Hercules (2014) and DC Extended Universe films: Wonder Woman (2017), Justice League (2017), Wonder Woman 1984 (2020), Zack Snyder's Justice League (2021).

- Amazons in television series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, Young Hercules, and Xena: Warrior Princess, The Legend of the Hidden City and Huntik: Secrets & Seekers and Supernatural.

Games

Amazons are featured in the following roleplay - and video games: Diablo, Heroes Unlimited, Aliens Unlimited, Amazon: Guardians of Eden, Flight of the Amazon Queen, A Total War Saga: Troy, Rome: Total War, Final Fantasy IV, Age of Wonders: Planetfall, Legend of Zelda series and Yu-Gi-Oh games.

Military units

- Russian general and statesman Grigory Potemkin, and then favourite of Catherine the Great created an Amazons Company in 1787. Wives and daughters of the soldiers of the Greek Battalion of Balaklava were enlisted and formed this unit.

- The Mino, or Minon, (Our Mothers) were a late 19th to early 20th-century all-female official military regiment of the former Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin). Since the early 18th-century women contingents had already joined the army, usually during deployment, in order to inflate the army size. However, women proved themselves courageous and effective in active combat, and a regular unit was established. Western observers, who had allegedly perceived certain Amazon-like physical and mental qualities in these women, came up with the trivial epithet Dahomey Amazons.[92]

Social and religious activism

- During the period 1905–1913, members of the militant Suffragette movement were frequently referred to as "Amazons" in books and newspaper articles.[93]

- In Ukraine Katerina Tarnovska leads a group called the Asgarda which claims to be a new tribe of Amazons.[94] Tarnovska believes that the Amazons are the direct ancestors of Ukrainian women, and she has created an all-female martial art for her group, based on another form of fighting called Combat Hopak, but with a special emphasis on self-defense.[94]

Science

The Neptune trojans, asteroids 60° ahead or beyond Neptune on its orbit, are individually named after mythological Amazons.

See also

- List of Amazons

- Action heroine

- Amazons (DC Comics)

- Matriarchy

- List of women warriors in folklore

- Women in the military

- Timeline of women in ancient warfare

- Ares (father of amazons)

- Shieldmaiden, female warrior in northern Europe

- Onna-bugeisha, female warrior in Japanese nobility

- Urduja, from Philippine mythology

- Women warriors in literature and culture

References

- ↑ Silver, Carly (July 29, 2019). "The Amazons Were More Than A Myth: Archaeological And Written Evidence For The Ancient Warrior Women". ATI. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- 1 2 Adrienne Mayor (September 22, 2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. ISBN 9780691147208. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ↑ Carlos Parada, Maicar Förlag. "AMAZONS". maicar. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Andreas David Mordtmann. "Die Amazonen : ein Beitrag zur unbefangenen Prüfung und Würdigung der ältesten Überlieferungen". Reader digitale sammlungen. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Ian Harvey (August 5, 2019). "The Fierce Amazon Warrior Women – What's Real and What's Myth". Vintage news. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ↑ Cartwright, Mark (November 14, 2019). "Amazon Women". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on Apr 10, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Jacob Stern (1 January 1996). On Unbelievable Tales. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-320-1.

- ↑ Hansen, William F. (26 April 2005). Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195300352 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Anton Westermann (1839). Paradoxographoi [romanized].: Scriptores rerum mirabilium graeci. Insunt (Aristotelis) Mirabiles auscultationes; Antigoni, Apollonii, Phlegontis Historiae mirabiles, Michaelis Pselli Lectiones mirabiles, reliquorum eiusdem generis scriptorum deperditorum fragmenta . Accedunt Phlegontis Macrobii et Olympiadum reliquiae et anonymi tractus De mulieribus, etc. sumptum fecit G. Westermann.

- ↑ Simon, Worrall (October 28, 2014). "Amazon Warriors Did Indeed Fight and Die Like Men". National Geographic. Archived from the original on Sep 20, 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Foreman, Amanda (April 2014). "The Amazon Women: Is There Any Truth Behind the Myth?". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on Sep 9, 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Schuster, Ruth (2 January 2020). "Tomb with Three Generations of 'Amazon' Warrior Women Found in Russia". Haaretz.

- 1 2 3 J. H. Blok (1995). The Early Amazons: Modern and Ancient Perspectives on a Persistent Myth. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10077-6.

- ↑ Hinge 2005, pp. 94–98

- ↑ "amazon | Etymology, origin and meaning of the name amazon by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ↑ Marylene Patou-mathis (1 October 2020). L'homme préhistorique est aussi une femme. Allary éditions. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-2-37073-342-9.

- 1 2 Haynes, Natalie (16 October 2014). "The Amazons: Lives & Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World by Adrienne Mayor, book review". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Amazons". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 790–791.

- ↑ Flavius Philostratus, Ellen Bradshaw Aitken, Jennifer K. Berenson Maclean (August 5, 2019). "Flavius Philostratus, On Heroes". The Center for Hellenic Studies. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "The Amazons - Adrienne Mayor". BBC Radio Four. 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound.

- 1 2 "Διονυσιακά/36 - Βικιθήκη". el.wikisource.org.

- ↑ Aeschylus, Suppliant Women.

- ↑ "The Amazons existed outside the range of normal human experience": P. Walcot (1984). "Greek Attitudes towards Women: The Mythological Evidence". Greece & Rome. jstor. 31 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1017/S001738350002787X. JSTOR 642368. S2CID 163008170. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ↑ M. Cyrino; M. Safran (8 April 2015). Classical Myth on Screen. Springer. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-1-137-48603-5.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, p. 1.173.1.

- ↑ John Man (October 23, 2017). "The real Amazons: how the legendary warrior women inspired fighters and feminists". BBC History Magazine. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ↑ Simon Worrall (October 28, 2014). "Amazon Warriors Did Indeed Fight and Die Like Men". National Geographic. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ↑ "HARMONIA". Theoi. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ↑ "ARES FAMILY - Greek Mythology". theoi com. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Adrienne Mayor, Josiah Ober (20 April 2018). "AMAZONS". Historynet. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ↑ Colin Quartermain (February 2, 2017). "BELLEROPHON IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY - Bellerophon and the Amazons". Greek legends and myths. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ "Epic Cycle". Livius org. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, p. 2.45–46.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, p. 3.52–55.

- ↑ Bruce Robert Magee. "The Amazon Myth in Western Literature". Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, p. 4.110.1.

- ↑ "Reading on Amazons". University of Washington. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ↑ "Suda Encyclopedia". Topostext. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ Sue Blundell; Susan Blundell (1995). Women in Ancient Greece p. 60. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- 1 2 Stéphane Gsell. "Boston 98.916 (Vase), from the Vulci necropolis". Tufts University. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- 1 2 Tobias Fischer-Hansen; Birte Poulsen (2009). From Artemis to Diana: The Goddess of Man and Beast. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 333–. ISBN 978-87-635-0788-2.

- 1 2 Page duBois (July 1991). Centaurs and Amazons: Women and the Pre-History of the Great Chain of Being. University of Michigan Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 0-472-08153-5.

- ↑ Florence Mary Bennett (1967). Religious Cults Associated With the Amazons. Library of Alexandria. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-4655-7683-5.

- ↑ Mayor, Adrienne (22 September 2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400865130 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Robert Bedrosian. "Eusebius' Chronicle". Attalus. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ↑ "Strategemata Polyaenus Macedo - Melber and Woelfflin, Teubner, 1887". Read Greek. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ↑ Greek Alexander Romance, 3.25–26

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Alexander, Chapter 46

- ↑ Tamid 32a

- ↑ "The Siege of Themiscyra". The last Diadoch. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ Lee Fratantuono (30 September 2017). Lucullus: The Life and Campaigns of a Roman Conqueror. Pen & Sword Books. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-4738-8363-5.

- ↑ Adrienne Mayor (22 September 2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-4008-6513-0.

- ↑ Friedhelm Hoffmann; Joachim Friedrich Quack (2018). Anthologie der demotischen Literatur. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 419–. ISBN 978-3-643-14029-6.

- ↑ A. S. WAY. "QUINTUS SMYRNAEUS 1 - THE FALL OF TROY". Theoi. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Books I-V, p. 4.

- ↑ Scholia on Pindar, Nemean Ode 3. 64

- ↑ "Justinus: Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories 2.4". Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ↑ Paulus Orosius, Historiae adversus paganos, I. 15

- ↑ Hygnius, p. 163, 30, 122, 223.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E5. 1

- ↑ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 2. 370 ff and 382 ff

- ↑ J. H. MOZLEY. "VALERIUS FLACCUS 1". Theoi. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ↑ D. WHITEHEAD (January 1996). "From Political Architecture to Stephanus Byzantius. Sources for the study of the ancient Greek polis". Mnemosyne. Brill. 49 (5): 612–615. doi:10.1163/1568525962610509. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ↑ Smith, William (26 April 1844). "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology". Taylor and Walton – via Google Books.

- ↑ Pritchett, W. Kendrick (1998). Studies in ancient Greek topography: Passes. University of California Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-520-09660-8. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ↑ Corinne Jouanno (January 2016). "Digenis Akritis, the Two-Blood Border Lord.pdf". Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond. Academia. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Vassílios Digenís Akritis (7 May 1998). Digenis Akritis: The Grottaferrata and Escorial Versions. Cambridge University Press. pp. xxvii. ISBN 978-0-521-39472-7.

- ↑ Tzetzes, Posthomerica 176-182

- ↑ The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Dover publications, Mineola, New York, 2006, cap. XVII, p. 103-104

- ↑ "New Frog Species Named After Fabled Female Warriors". National Geographic. 2018-07-20. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ↑ It has been suggested that what Orellana actually engaged was an especially warlike tribe of Native Americans whose warrior men wore long hair and thus appeared to be women. See Theobaldo Miranda Santos, Lendas e mitos do Brasil ("Brazil's legends and myths"), Companhia Editora Nacional, 1979.

- ↑ Lendas (PDF). Chiaroscuro Studios. p. 14.

- ↑ Lendas (PDF). Chiaroscuro Studios. 2018. p. 14.

- ↑ Raymond E. Crist. "Amazon River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Amazons in Art". Amazonation. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Jochen Fornasier (August 19, 2010). "Die Amazonen zwischen Mythos und Realität - Auf den Spuren Penthesileias". Wissenschaft DE. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ↑ Annaliese Elaine Patten (March 22, 2012). "The Amazon in Greek Art". Portland State University. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Erin W. Leal (March 22, 2012). "Roman Interpretations of the Amazons through Literature and Art". Ancient EU. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Winfried Schleiner (March 22, 2012). ""Divina Virago": Queen Elizabeth as an Amazon". Studies in Philology. Jstor. 75 (2): 163–180. JSTOR 4173965. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ↑ Thomas Hearne, De rebus Britannicis collectanea, vol. 2 (London, 1774), pp. 666-9

- ↑ "German masters of the nineteenth century : paintings and drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany / The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York :: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications". libmma.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 2015-09-30.

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- ↑ Sir Arthur Evans, Andrew Lang, Gilbert Murray, Frank Byron, Jevons, Sir John Linton Myres, William Warde Fowler (1908). Anthropology and the Classics: Six Lectures Delivered Before the University of Oxford. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-7905-5822-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Semi (September 27, 2014). "ourney to the Black Sea village of the Amazons". Route nach Unbekannte Straße. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Village of Amazons to be recreated in Samsun park". Today's Zaman. June 10, 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ↑ P. Greenhalgh and E. Eliopoulos, 63

- ↑ "VI. Zug und Kampf der Amazonen gegen Athen", Die Amazonen in der attischen Literatur und Kunst, De Gruyter, pp. 31–89, 1875-12-31, doi:10.1515/9783112406069-007, ISBN 9783112406069, retrieved 2022-06-19

- ↑ Bob Gross (September 22, 2002). "Band of sisters: the Amazon light cavalry.(Book Review)". Archive. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ↑ Sensation Comics #6 (June 1942)

- ↑ Jay, Joslyn (2020-01-24). "9 to 5 (1980) Review: Classics Revisited #11". Flickside. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ↑ Sir Burton, Richard Francis (1893). "A mission to Gelele, King of Dahome : with notices of the so-called "Amazons" the grand customs, the human sacrifices, the present state of the slave trade and the negro's place in nature". Archive. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ↑ Wilson, Gretchen "With All Her Might: The Life of Gertrude Harding, Militant Suffragette" (Holmes & Meier Publishing, April 1998)

- 1 2 "Ukraine's Asgarda martial arts program recasts Amazon warrior women | Public Radio International". Pri.org. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

Sources

Primary

- Homer. "Iliad". Tufts University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Diodorus Siculus. "Bibliotheca Historica, Books I-V". Tufts University. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Herodotus. "The Histories". Tufts University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Bacchylides. "Epinicians". Tufts University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Aeschylus. "Prometheus Bound". Tufts University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Aeschylus. "Suppliant Women". Tufts University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Hygnius, Gaius Julius. "Fabulae". Theoi Project. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

Secondary

- "Theoi Greek Mythology". Theoi Project. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Hinge, George (2005). "Herodot zur skythischen Sprache. Arimaspen, Amazonen und die Entdeckung des Schwarzen Meeres". Glotta (in German). 81: 86–115.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2017). "Amazons in the Iranian World". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, A.S. (1989). "Amazons". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Further reading

- Adams, Maeve. "Amazons." The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies (2016): 1–4.

- "AMAZONS Women of the Steppe and the Idea of the Female Warrior". In: Ball, Warwick. The Eurasian Steppe: People, Movement, Ideas. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022. pp. 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474488075-010

- Dowden, Ken. “THE AMAZONS: DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTIONS”. In: Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 140, no. 2 (1997): 97–128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41234269.

- Fialko, Elena (2018). "Scythian Female Warriors in the South of Eastern Europe". In: Folia Praehistorica Posnaniensia 22 (lipiec), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.14746/fpp.2017.22.02.

- Guliaev, V. I. (2003). "Amazons in the Scythia: New finds at the Middle Don, Southern Russia". In: World Archaeology, 35:1, 112–125. DOI: 10.1080/0043824032000078117

- Hardwick, Lorna (1990). "Ancient Amazons - Heroes, Outsiders or Women?". In: Greece & Rome, 37, pp. 14–36. doi:10.1017/S0017383500029521

- Liccardo, Salvatore. "Different Gentes, Same Amazons: The Myth of Women Warriors at the Service of Ethnic Discourse." Medieval History Journal 21.2 (2018): 222–250.

- Mayor, Adrienne. The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7zvndm. online review

- Maartel Bremer, Jan. "THE AMAZONS IN THE IMAGINATION OF THE GREEKS". In: Acta Antiqua 40, 1-4 (2000): 51–59. Accessed Jul 17, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1556/aant.40.2000.1-4.6

- Toler, Pamela D. Women warriors: An unexpected history (Beacon Press, 2019).

- von Rothmer, Dietrich, Amazons in Greek Art (Oxford University Press, 1957)

- Vovoura, Despoina. “Women Warriors(?) And the Amazon Myth: The Evidence of Female Burials with Weapons in the Black Sea Area”. In: The Greeks and Romans in the Black Sea and the Importance of the Pontic Region for the Graeco-Roman World (7th Century BC-5th Century AD): 20 Years On (1997-2017): Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress on Black Sea Antiquities (Constanţa – 18–22 September 2017). Edited by Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, Alexandru Avram, and James Hargrave. Archaeopress, 2021. pp. 118–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1pdrqhw.22.

- Wilde, Lyn Webster. On the trail of the women warriors: The Amazons in myth and history ( Macmillan, 2000).

Other languages

- Bergmann, F. G. Les Amazones dans l'histoire et dans la fable (1853) (in French)

- Klugmann, A. Die Amazonen in der attischen Literatur und Kunst (1875) (in German)

- Krause, H. L. Die Amazonensage (1893) (in German)

- Lacour, F. Les Amazones (1901) (in French)

- Mordtmann, Andreas David. Die Amazonen (Hanover, 1862) (in German)

- Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft

- Roscher, W. H., Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (in German)

- Santos, Theobaldo Miranda. Lendas e mitos do Brasil (Companhia Editora Nacional, 1979) (in Portuguese)

- Stricker, W. Die Amazonen in Sage und Geschichte (1868) (in German)