Ferdinand Augustin Haller von Hallerstein, or Liu Songling | |

|---|---|

| Born | 27 August 1703 |

| Died | 29 October 1774 (aged 71) |

| Known for | first astrolabe at the Beijing observatory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, demography, mathematics |

| Institutions | Head of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau and Board of Mathematics in Peking |

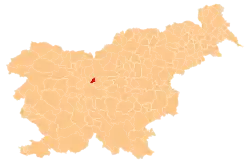

Ferdinand Augustin Haller von Hallerstein (Slovene: Ferdinand Avguštin Haller von Hallerstein; 27 August 1703 – 29 October 1774), also known as August Allerstein or by his Chinese name Liu Songling (simplified Chinese: 刘松龄; traditional Chinese: 劉松齡; pinyin: Liú Sōnglíng), was a Jesuit missionary and astronomer from Carniola (then Habsburg monarchy, now Slovenia). He was active in 18th-century China and spent 35 years at the imperial court of the Qianlong Emperor as the head of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau and Board of Mathematics. He created an armillary sphere with rotating rings at the Beijing Observatory and was the first demographer in China who precisely calculated the exact number of Chinese population of the time (198,214,553). He also participated in Chinese cartography, serving concurrently as a missionary, "cultural ambassador" and mandarin between 1739 and 1774.

Life and work

Hallerstein was born on 27 August 1703 in Ljubljana[1][2][3] (in older sources in Mengeš, incorrectly citing the date as 18 August 1703),[1][4] Carniola (then part of the Habsburg monarchy, now in Slovenia)[5] as a member of the Hungarian branch of the famous Haller von Hallerstein family from Nuremberg, Germany. He was baptized Ferdinandus Augustinus Haller L.B. ab Hallerstein in Ljubljana on 28 August 1703.[6] He spent his youth in Mengeš, where his family owned Ravbar Castle, and studied at the Jesuit college in Ljubljana.[7]

He was a member of the Academy of Sciences in all the three cities, from Germany and Vienna, where he mainly published his scientific disputes, to Rome and Lisbon, the city of his correspondence and of his personal friend – the Queen of Portugal. It was from Portugal that he travelled to India as a missionary, where he worked in Goa and Macau and then continued his travel to Beijing, China.

The former Beijing Astronomical Observatory, now a museum, still hosts the armillary sphere with rotating rings, which was made under Hallerstein's leadership and is considered the most prominent astronomical instrument.

His list and the Chinese translation reached Europe in 1779. The Chinese emperors objected to census-taking, or at least to census-publication, lest the Chinese might recognize their strength and grow restless. It confirms all the calculations of one of his predecessors, Father Amiot and affords proof of the progressive increase of the Chinese population. In the 25th year, he found 196,837,977 souls, and in the following year, 198,214,624. Hallerstein's census is to be found in "Déscription Générale de la Chine", p. 283.

He was buried in the Jesuits' Zhalan Cemetery in Beijing.

Legacy

In Budapest, translations of his letters were published in the 18th century.

A part of the Third Conference of the European Society for the History of Science was dedicated to Hallerstein and his transfer of mid-European science to Beijing and back. In recent years he has attracted the attention of Chinese historians as the creator of the most intriguing astronomic instrument at the old Beijing observatory, the spherical astrolabe, a "celestial globe".

The asteroid 15071 Hallerstein is named after Hallerstein.[8]

References

- 1 2 Hribar, Viljem Marjan (2003). Mandarin: Hallerstein, kranjec na kitajskem dvoru. Mengeš: Muzej Mengeš. p. 144.

- ↑ "Spomin na Hallersteina, astronoma, ki ga je pot zanesla na Kitajsko". RTV SLO. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ "Hallerstein je v Sloveniji pustil neizbrisljiv pečat". STA Znanost. STA. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ Umek, Ema; Prosen, Marijan (1990). "Avguštin Hallerstein". Enciklopedija Slovenije. Vol. 4. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga. p. 5.

- ↑ Sandi Sitar, Sto slovenskih znanstvenikov (Ljubljana: Prešernova družba, 1987), 25.

- ↑ Taufbuch. Ljubljana – Sv. Nikolaj. 1700–1712. p. 106. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ Sandi Sitar, Sto slovenskih znanstvenikov (Ljubljana: Prešernova družba, 1987), 25.

- ↑ "Slovenski jezuit, ki ima svoj asteroid" [A Slovene Jesuit Who Has His Own Asteroid]. MMC RTV Slovenija (in Slovenian). RTV Slovenija.