The Fichte-Bunker is a nineteenth-century gasometer in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin, Germany that was made into an air-raid shelter in World War II and subsequently was used as a shelter for the homeless and for refugees, in particular for those fleeing East Berlin for the West. It is the last remaining brick gasometer in Berlin.

The Fichte-Bunker is located between Fichtestraße and Körtestraße in an area of Jugendstil apartment houses, many of which are now under historic protection. The gasometer itself is protected,[1] but in September 2006 the State of Berlin's Real Property Fund sold it to private investors and residences have now been constructed on the roof.

Construction and technical data

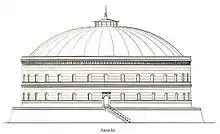

The Fichte-Bunker was constructed in 1874 for the Municipal Gasholder Authority to the design of Johann Wilhelm Schwedler.[1] It was the second of four gasometers he designed for Berlin's street lighting;[2] the first was in Friedrichshain and has since been destroyed. Both were topped with the "Schwedler cupola", an engineering innovation of his that used an unsupported curved steel vault to span diameters of up to 45 metres (148 ft).[3]

The gasometer is a cylinder 56 metres (184 ft) in diameter, 21 metres (69 ft) high exclusive of the cupola[2] and 27 metres (89 ft) high in total. Its form was based on an 1827 design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel for a circular church.[3][4] The capacity of the telescoping gas container was 30,000 cubic metres.[5]

History

The Kreuzberg gasometer was one of four built to supply gas for street lighting during Berlin's explosive growth in the 1870s.

After the introduction of electric street lighting, the gasometer was taken out of service in 1922 and until 1940 stood empty. At the end of 1940, Fritz Todt, Inspector-General of Buildings for the capital, had it converted into a 6-level air-raid shelter, one of three intended primarily for the protection of women and children. (The other two were side by side in Wedding). These were the largest shelters built anywhere in the Reich in the crash programme of shelter construction.[6] The roof, interior walls and floors were constructed of reinforced concrete up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick. The contractors, Siemens-Bauunion, used predominantly prisoners-of-war and forced labourers.[7][8] Originally the shelter was planned for 6,000 people, but during the air raid of 3 February 1945, some 30,000 people took shelter[9] in the approximately 750 individual rooms, which are in many cases only 5 to 7 square meters.[10] In 1944-45, it sheltered Germans expelled from the eastern territories as well as Berliners.[11] Despite heavy bombardment, the bunker survived the war more or less undamaged.

After the war, the Fichte-Bunker was initially a much needed place of refuge for the displaced.[12] It was used as a juvenile detention facility[13] and as a home for the elderly. It was also typically the first place where refugees from East Germany stayed.[14][15][16] Finally it became a homeless shelter,[17] which rented rooms to the needy for 2.50 DM a night. Conditions were notoriously bad; it was called the Bunker der Hoffnungslosen ("Bunker of the Hopeless") and a reporter who went in incognito found it unbearable.[18]

The facility was closed for health reasons in 1963 and from then until reunification, the city used the building as a storehouse for part of the Senate Reserve, goods and provisions which the Senate of West Berlin was legally required to maintain in case of a second Berlin Blockade.[2]

After 1990, the Fichte-Bunker again stood empty; entrance was only possible on special tours.

Luxury housing

In September 2006, the State of Berlin's Real Property Fund sold the building and approximately 8,000m2 of land to the newly formed development company SpeicherWerk Wohnbau GmbH. The investors planned to construct luxury 2-storey condominiums on top of the former gasometer and build townhouses and a five-storey apartment building on the land around the building.[2][19][20] Despite objections from neighbours to the density of the development, planning permission was granted and work began in December 2007; the freestanding residences were completed in 2009.[7][21] In spring 2008, there was concern about possible violation of the historic building code,[22] and in summer 2009 the scaffolding around the gasometer was set on fire as part of Action Weeks by squatters and opponents of demolition of housing to build for the rich.[23] In spring 2010, completion of the "Circlehouse" of 13 condominiums on top of the bunker was announced. Designed by architect Paul Ingenbleek and engineer Michael Ernst, they have rooftop gardens in front of the lower storey and front walls of steel and glass and are reached by means of a bridge from a tower which contains a lift and stairs.[3]

References

- 1 2 Denkmale in Berlin - 09031136, Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung Berlin, 25 March 2008 (German - Monuments in Berlin).

- 1 2 3 4 "Leben auf dem Denkmal", Berliner Zeitung 1 February 2007 (German - Life on the Monument).

- 1 2 3 Umbau Fichtebunker in Berlin Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, Stahl-Informations-Zentrum, 9 March 2010 (German - Conversion, Fichte-Bunker in Berlin).

- ↑ Kristin Feireiss and Julius Posener, Berlin - Denkmal oder Denkmodell? : Architektonische Entwürfe für den Aufbruch in das 21. Jahrhundert / Berlin - Monument ou modèle de pensée?: Projets architecturaux pour l'entrée dans de 21ème siècle, Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin, Berlin: Ernst, 1988, ISBN 3-433-02285-2, p. 252 (German, French).

- ↑ Gasbehälter (Gasometer) und Gaswerke in Deutschland (German), retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ↑ Dietmar Arnold, Reiner Janick, Sirenen und gepackte Koffer: Bunkeralltag in Berlin, Berlin: Links, 2003, ISBN 3-86153-308-1, p. 5 (German).

- 1 2 "Kreuzberg: Schöner Wohnen auf dem Fichte-Bunker", Der Tagesspiegel 6 February 2008 (German - Live more beautifully atop the Fichte-Bunker).

- ↑ Horst Unsold, "Die Gasstation in der Fichtestraße", Kreuzberger Chronik 95, March 2008 (German - The Gas Depot in Fichtestraße).

- ↑ Arnold and Janick, p. 105.

- ↑ Karin Schmidl, "Für den Bunker wird ein Investor gesucht", Berliner Zeitung January 3, 1997 (German - Investor Sought for the Bunker).

- ↑ Museums Journal 2005, p. 91 (German).

- ↑ Arnold and Janick, p. 126: "Der Großbunker in der Fichtestraße bietet täglich rund 1 600 Vertriebenen, Umquartierten und entlassenen Kriegsgefangenen ein Obdach - The huge bunker in Fichtestraße daily offers a refuge to some 1,600 exiles, transients and released prisoners of war".

- ↑ Jennifer V. Evans, "Life Among the Ruins: Sex, Space, and Subculture in Zero Hour Berlin", in Berlin Divided City, 1945–1989, ed. Philip Broadbent and Sabine Hake, New York / Oxford: Berghahn, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84545-755-6, pp. 11–22, p. 19.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Reichhardt, Joachim Drogmann, Hanns U. Treutler, Berlin: Chronik der Jahre 1951-1954, Landesarchiv Berlin, Berlin: Spitzing, 1968, OCLC 1024670, p. 440: "im Fichtebunker . . . , wo politische Flüchtlinge untergebracht sind - in the Fichte-Bunker . . . , where political refugees are housed".

- ↑ Curt Riess, Berlin Berlin 1945-53, 1953, repr. ed. Stefan Damm Berlin: Bostelmann & Siebenhaar, 2002, ISBN 3-934189-81-4, p. 270: "Diese Flüchtlinge, die in des Wortes wahrste Bedeutung die Freiheit gewählt hatten, kamen zuerst einmal im Fichtebunker unweit des Flugplatzes Tempelhof, im amerikanischen Sektor von Berlin, unter - These refugees, who had chosen freedom in the truest sense of the word, were first housed in the Fichte-Bunker, not far from Tempelhof Airport, in the American Sector".

- ↑ Frank Roggenbuch, Das Berliner Grenzgängerproblem: Verflechtung und Systemkonkurrenz vor dem Mauerbau, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008, ISBN 3-11-020344-8, p. 141: "im Kreuzberger so genannten »Fichtebunker« (wo üblicherweise politische Flüchtlinge untergebracht waren) - in the so-called 'Fichte-Bunker' in Kreuzberg (where political refugees were routinely housed)".

- ↑ Arnold and Janick, p. 134: "Im September 1956 ziehen die letzten Flüchtlinge aus, einen Tag später belegen Obdachlose die freigewordenen Kammern - In September 1956 the last refugees move out, a day later homeless people occupy the vacated rooms".

- ↑ Arnold and Janick, pp. 134-35: "Nach drei Stunden hab' ich den Bunkerkoller. Ich weiß nicht, ob die Sonne scheint, ob es regnet, ob es Nacht ist, ich drehe durch. Wie um alles in der Welt halten die Menschen es hier aus? - After three hours I've got the bunker madness. I don't know if the sun is shining, if it's raining, if it's night, I'm cracking up. For the sake of everything in the world, how do people put up with this place?"

- ↑ Thomas Fülling, "Wohnen auf dem Bunkerdach", Berliner Morgenpost 4 June 2008 (German - Living on the roof of the bunker).

- ↑ "Der Fichtebunker in Kreuzberg" Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, News, Beton.org, 23 June 2008.

- ↑ "Sportplätze in der Stadt: Ein Grundrecht auf Grölen", Der Tagesspiegel 22 July 2009 (German - Sports grounds in the city: a fundamental right to yell).

- ↑ "Illegale Schwarzbauten auf dem Fichtebunker?" Press Release, Initiative Fichtebunker Berlin, 4 May 2008 German - Illegal building on the sly on top of the Fichte-Bunker?).

- ↑ "Autonome wollen Räumung verhindern", Der Tagesspiegel 16 June 2009 (German - Activists want to stop clearance).

External links

- Reiner Janick and Gudrun Neumann, Bunkereinbau Gasometer Fichtestraße, Berliner Unterwelten e.V. (German)

- Aro Kuhrt, Der Fichtebunker, Berlin:Street, Berlin für Neugierige (German)

- SpeicherWerk Wohnbau GmbH Project site (German)

- Stop-motion film of 3 days' construction on top of the Fichte-Bunker, 8 March 2008 (YouTube)