Finger binary is a system for counting and displaying binary numbers on the fingers of either or both hands. Each finger represents one binary digit or bit. This allows counting from zero to 31 using the fingers of one hand, or 1023 using both: that is, up to 25−1 or 210−1 respectively.

Modern computers typically store values as some whole number of 8-bit bytes, making the fingers of both hands together equivalent to 11⁄4 bytes of storage—in contrast to less than half a byte when using ten fingers to count up to 10.[1]

Mechanics

In the binary number system, each numerical digit has two possible states (0 or 1) and each successive digit represents an increasing power of two.

Note: What follows is but one of several possible schemes for assigning the values 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc. to fingers, not necessarily the best. (see below the illustrations.): The rightmost digit represents two to the zeroth power (i.e., it is the "ones digit"); the digit to its left represents two to the first power (the "twos digit"); the next digit to the left represents two to the second power (the "fours digit"); and so on. (The decimal number system is essentially the same, only that powers of ten are used: "ones digit", "tens digit" "hundreds digit", etc.)

It is possible to use anatomical digits to represent numerical digits by using a raised finger to represent a binary digit in the "1" state and a lowered finger to represent it in the "0" state. Each successive finger represents a higher power of two.

With palms oriented toward the counter's face, the values for when only the right hand is used are:

| Pinky | Ring | Middle | Index | Thumb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power of two | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| Value | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

When only the left hand is used:

| Thumb | Index | Middle | Ring | Pinky | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power of two | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| Value | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

When both hands are used:

| Left hand | Right hand | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thumb | Index | Middle | Ring | Pinky | Pinky | Ring | Middle | Index | Thumb | |

| Power of two | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| Value | 512 | 256 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

And, alternately, with the palms oriented away from the counter:

| Left hand | Right hand | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinky | Ring | Middle | Index | Thumb | Thumb | Index | Middle | Ring | Pinky | |

| Power of two | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| Value | 512 | 256 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

The values of each raised finger are added together to arrive at a total number. In the one-handed version, all fingers raised is thus 31 (16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1), and all fingers lowered (a fist) is 0. In the two-handed system, all fingers raised is 1,023 (512 + 256 + 128 + 64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1) and two fists (no fingers raised) represents 0.

It is also possible to have each hand represent an independent number between 0 and 31; this can be used to represent various types of paired numbers, such as month and day, X-Y coordinates, or sports scores (such as for table tennis or baseball). Showing the time as hours and minutes is possible using 10 fingers, with the hour using 4 fingers (0-23) and the minutes using 6 fingers (0-59).

Examples

Right hand

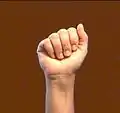

0 = empty sum

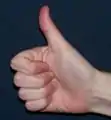

0 = empty sum 1 = 1

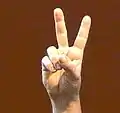

1 = 1 2 = 2

2 = 2.JPG.webp) 4 = 4

4 = 4 6 = 4 + 2

6 = 4 + 2 7 = 4 + 2 + 1

7 = 4 + 2 + 1 14 = 8 + 4 + 2

14 = 8 + 4 + 2 16 = 16

16 = 16 19 = 16 + 2 + 1

19 = 16 + 2 + 1 26 = 16 + 8 + 2

26 = 16 + 8 + 2 28 = 16 + 8 + 4

28 = 16 + 8 + 4 30 = 16 + 8 + 4 + 2

30 = 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 31 = 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1

31 = 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1

Left hand

When used in addition to the right.

512 = 512

512 = 512 256 = 256

256 = 256 768 = 512 + 256

768 = 512 + 256 448 = 256 + 128 + 64

448 = 256 + 128 + 64 544 = 512 + 32

544 = 512 + 32 480 = 256 + 128 + 64 + 32

480 = 256 + 128 + 64 + 32 992 = 512 + 256 + 128 + 64 + 32

992 = 512 + 256 + 128 + 64 + 32

Negative numbers and non-integers

Just as fractional and negative numbers can be represented in binary, they can be represented in finger binary.

Negative numbers

Representing negative numbers is extremely simple, by using the leftmost finger as a sign bit: raised means the number is negative, in a sign-magnitude system. Anywhere between −511 and +511 can be represented this way, using two hands. Note that, in this system, both a positive and a negative zero may be represented.

If a convention were reached on palm up/palm down or fingers pointing up/down representing positive/negative, you could maintain 210 −1 in both positive and negative numbers (−1,023 to +1023, with positive and negative zero still represented).

Fractions

Dyadic fractions

Fractions can be stored natively in a binary format by having each finger represent a fractional power of two: . (These are known as dyadic fractions.)

Using the left hand only:

| Pinky | Ring | Middle | Index | Thumb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/16 | 1/32 |

Using two hands:

| Left hand | Right hand | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinky | Ring | Middle | Index | Thumb | Thumb | Index | Middle | Ring | Pinky |

| 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/16 | 1/32 | 1/64 | 1/128 | 1/256 | 1/512 | 1/1024 |

The total is calculated by adding all the values in the same way as regular (non-fractional) finger binary, then dividing by the largest fractional power being used (32 for one-handed fractional binary, 1024 for two-handed), and simplifying the fraction as necessary.

For example, with thumb and index finger raised on the left hand and no fingers raised on the right hand, this is (512 + 256)/1024 = 768/1024 = 3/4. If using only one hand (left or right), it would be (16 + 8)/32 = 24/32 = 3/4 also.

The simplification process can itself be greatly simplified by performing a bit shift operation: all digits to the right of the rightmost raised finger (i.e., all trailing zeros) are discarded and the rightmost raised finger is treated as the ones digit. The digits are added together using their now-shifted values to determine the numerator and the rightmost finger's original value is used to determine the denominator.

For instance, if the thumb and index finger on the left hand are the only raised digits, the rightmost raised finger (the index finger) becomes "1". The thumb, to its immediate left, is now the 2s digit; added together, they equal 3. The index finger's original value (1/4) determines the denominator: the result is 3/4.

Rational numbers

Combined integer and fractional values (i.e., rational numbers) can be represented by setting a radix point somewhere between two fingers (for instance, between the left and right pinkies). All digits to the left of the radix point are integers; those to the right are fractional.

Decimal fractions and vulgar fractions

Dyadic fractions, explained above, have limited use in a society based around decimal figures. A simple non-dyadic fraction such as 1/3 can be approximated as 341/1024 (0.3330078125), but the conversion between dyadic and decimal (0.333) or vulgar (1/3) forms is complicated.

Instead, either decimal or vulgar fractions can be represented natively in finger binary. Decimal fractions can be represented by using regular integer binary methods and dividing the result by 10, 100, 1000, or some other power of ten. Numbers between 0 and 102.3, 10.23, 1.023, etc. can be represented this way, in increments of 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, etc.

Vulgar fractions can be represented by using one hand to represent the numerator and one hand to represent the denominator; a spectrum of rational numbers can be represented this way, ranging from 1/31 to 31/1 (as well as 0).

Finger ternary

In theory, it is possible to use other positions of the fingers to represent more than two states (0 and 1); for instance, a ternary numeral system (base 3) could be used by having a fully raised finger represent 2, fully lowered represent 0, and "curled" (half-lowered) represent 1. This would make it possible to count up to 242 (35−1) on one hand or 59,048 (310−1) on two hands. In practice, however, many people will find it difficult to hold all fingers independently (especially the middle and ring fingers) in more than two distinct positions.

See also

References

- ↑ Since computers typically store data in a minimum size of one whole byte, fractions of a byte are used here only for comparison.

- Pohl, Frederik (2003). Chasing Science (reprint, illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7653-0829-0.

- Pohl, Frederik (1976). The Best of Frederik Pohl. Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 363.

- Fahnestock, James D. (1959). Computers and how They Work. Ziff-Davis Pub. Co. p. 228.