| First Battle of Komárom | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

The First Battle, a painting by Mór Than | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 18,884 - I. corps: 9,465 - III. corps: 9,419 - a part of VIII. corps: 4249[1] 62 cannons Did not participate: VII. corps: 9,043 men 45 cannons[2] |

Total: 33,487 - II. corps: 13,489 - III. corps: 12,088 - IV. (siege) corps Lederer division: 7910 108 cannons[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total: 800 |

Total: 671 33 dead 149 wounded 489 missing and captured[2] 7 heavy siege cannons and mortars captured by the Hungarians[3] | ||||||

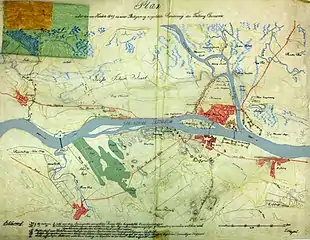

The First battle of Komárom was one of the most important battles of the Hungarian War of Independence, fought on 26 April 1849, between the Hungarian and the Austrian Imperial main armies, which some consider ended as a Hungarian victory, while others say that actually it was undecided. This battle was part of the Hungarian Spring Campaign. After the revolutionary army attacked and broke the Austrian siege of the fortress, the Imperials, having received reinforcements which made them numerically very superior to their enemies, successfully counterattacked, but after stabilising their situation, they retreated towards Győr, leaving the trenches and much of their siege artillery in Hungarian hands. By this battle the Hungarian revolutionary army relieved the fortress of Komárom from a very long imperial siege, and forced the enemy to retreat to the westernmost margin of the Kingdom of Hungary. After this battle, following a long debate among the Hungarian military and political leaders about whether to continue their advance towards Vienna, the Habsburg capital, or towards the Hungarian capital, Buda, whose fortress was still held by the Austrians, the second option was chosen.

Background

The main purpose of the 1849 Hungarian Spring Campaign led by Artúr Görgei was to push the Habsburg main armies out of Hungary towards Vienna. The first phase of the Spring Campaign was successful, and the Hungarian victory at Isaszeg[4] (6 April 1849), forced the imperial forces to retreat from the territory east of the Hungarian capitals Pest and Buda. On 7 April 1849 the Hungarian commanders elaborated another plan for the second phase of the campaign. According to this the Hungarian army was to split: General Lajos Aulich remained in front of Pest with his Hungarian II Corps and Colonel Lajos Asbóth's division, demonstrating to make the imperials believe that the whole Hungarian army was there; thus diverting their attention from the north, where the real Hungarian attack was to start with I, III and VII Corps moving west along the northern bank of the Danube to Komárom, to relieve it from the imperial siege.[5] Kmety's division of VII Corps was to cover the three corps's march, and after I and III Corps had occupied Vác, that division was to secure the town, while the rest of the troops together with the two remaining divisions of VII Corps were to advance to the Garam river, then head south to relieve the northern section of the Austrian siege of the fortress of Komárom.[5] After this, they had to cross the Danube and relieve the southern section of the siege. In the event that all this was completed successfully, the imperials would have only two choices: to retreat from Middle Hungary towards Vienna, or to face encirclement in the Hungarian capitals.[5] This plan was very risky (as was the first plan of the Spring Campaign too) because if Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz had discovered that only one Hungarian corps remained in front of Pest, he could have attacked and destroyed Aulich's force, and thereby could easily cut the lines of communication of the main Hungarian army, and even occupy Debrecen, the seat of the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament and the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary); or he could encircle the three corps advancing to relieve Komárom.[6] To secure the success of the Hungarian army, the National Defense Committee sent 100 wagons of munitions from Debrecen.[3] In the Battle of Vác on 10 April the Hungarian III Corps, led by János Damjanich defeated Ramberg's division led by Major General Christian Götz, who was mortally wounded.[7]

Even after this battle, the imperial high command led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz was unsure whether the main Hungarian army was still in front of Pest or had already moved north to relieve Komárom. They still thought it possible that it was only a subsidiary formation that had attacked Vác and was moving towards the besieged Hungarian fortress.[8] When Windisch-Grätz finally seemed to grasp what was really happening, he wanted to make a powerful attack against the Hungarians at Pest on 14 April, then to cross the Danube at Esztergom, and cut across the path of the army which was marching towards Komárom, but his corps commanders, General Franz Schlik and Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić refused to obey his commands, so his plan, which could have caused serious problems for the Hungarian armies, was not realized.[9]

.jpg.webp)

Because of his series of defeats at the hands of the Hungarians from the start of the Spring Campaign, on 12 April emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria relieved Windisch-Grätz of his command. Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden, the former military governor of Vienna, was designated commander-in-chief in his place, but until Welden arrived, Windisch-Grätz had to hand over to Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić as interim commander of the imperial armies in Hungary.[10] But this change in the leadership of the imperial forces did not bring lucidity and organization to the imperial high command, because the first order Jelačić gave after his interim command began was to call off Windisch-Grätz's plan of concentrating the imperial armies around Esztergom, and to end any chance of carrying out this by no means bad plan.[10]

Görgey, who had installed his headquarters in Győr after the battle there, ordered Damjanich's III Corps to advance towards Léva on 11 April, and Klapka's I Corps on the 12th. Their place in Vác was taken by VII Corps under András Gáspár, then after that too departed on the same way, Vác was occupied by György Kmety's division.[11] On 15–17 April the Hungarian army consisting of Klapka's I Corps, Damjanich's III Corps, and two divisions of VII Corps reached the Garam river, under the overall leadership of General Artúr Görgei.[12] Here, on 19 April, at Nagysalló, they met with the troops of Lieutenant General Ludwig von Wohlgemuth and his new imperial troops mustered from the following Habsburg hereditary lands: Styria, Bohemia, Moravia and the capital Vienna, and reinforced with Jablonowski's division (which had fought in the Battle of Vác 10 days earlier). The imperials were defeated and retreated towards Érsekújvár.[13] The Hungarian victory of Nagysalló brought about serious results. It opened the way towards Komárom, bringing its relief to within just a couple of days’ march.[13] At the same time it put the imperials in the situation of being incapable of stretching their troops across the very large front which this Hungarian victory created, so instead of uniting their troops around Pest and Buda, as they had planned, Feldzeugmeister Welden had to order the retreat from Pest which was in danger of being caught in the Hungarian pincers.[13] When he learned about the defeat on the morning of 20 April, he wrote to Lieutenant General Balthasar Simunich, the commander of the forces besieging Komárom, and to Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, the Minister-President of the Austrian Empire, telling them that in order to secure Vienna and Pozsony from a Hungarian attack he was forced to withdraw the imperial forces from Pest and even from Komárom.[14] He also wrote that the morale of the imperial troops was very low, and because of this they could not fight another battle for a while without suffering another defeat.[15] So the next day he ordered the evacuation of Pest, leaving a substantial garrison in the fortress of Buda to defend it against Hungarian attack. He ordered Jelačić to remain for a while in Pest, and then to retreat towards Eszék in Bácska, where the Serbian insurgents, allied with the Austrians, were in a grave situation after the victories of the Hungarian armies led by Mór Perczel and Józef Bem.[16]

Prelude

On 20 April the Hungarian VII Corps reached Nagybénye, then Kéménd, where it encountered a brigade of the Imperial II Corps led by Major General Franz Wyss coming from Párkány. The Austrians were forced to cross the Danube and retreat to Esztergom, but General András Gáspár did not send his cavalry to pursue the enemy,

even though he had the chance to cause them heavy losses.[17]

On 20 April, the Hungarian I and III Corps started their march towards Komárom.[18] On 22 April, the two Hungarian corps reached Komárom, breaking the northern section of the imperial blockade around the fortress.[19] On the same day, the garrison of Komárom broke out from the Nádor defense line against Sossay's brigade on the Csallóköz, forcing the imperials to retreat to Csallóközaranyos, then to Nyárasd.[19] The imperials lost 50 men and 30 horses,[19] losing also the connection with the Austrian siege corps from the right bank of the Danube, as the result of the fact that the Hungarian sortie troops, under the command of General János Lenkey, destroyed the bridge from Lovad across the Danube.[20] Hearing that Lieutenant General Wohlgemuth, who had retreated west of the river Vág, after his defeat at Nagysalló, was now advancing east again towards Érsekújvár, Görgei ordered the newly arrived VII Corps to deploy at Perbete, to secure the rear of the Hungarian army against possible attack.[19] The rest of the Hungarian corps were waiting the raft bridge over the Danube to be finished, which after intense work, was finished in the night of 25 to 26 April.[20]

The Hungarian chief of staff Colonel József Bayer was designed to elaborate the battle plan for the liberation of Komárom, but, because he was against this maneuver, called in sick, so General György Klapka assumed this responsibility.[20] According to this, five brigades were to cross the Danube during the night of 25/26 April: Kiss's and Kökényessy's brigades were to cross on the raft bridge constructed in haste to replace the pontoon bridge destroyed by the Imperials, and to deploy in the bridgehead to the right of the so-called Star rampart (Csillagsánc); then they were to be followed by Sulcz's and Zákó's brigades of I Corps deploying on their right, occupying the redoubts on the right wing of the fortress; and Dipold's brigade was to cross before midnight on boats and prepare to attack towards Újszőny. The attack was to be started by Colonel Pál Kiss's brigade against the Monostor fortress, also known as the Sandberg, with Kökényessy's brigade in support.[21] Lieutenant-Colonel Bódog Bátori Sulcz's brigade was to attack and take Újszőny. Then all these brigades were to attack the open ground beyond the Monostor, while a strong detachment sent across the river from the Danube island by Major General Richard Guyon was to attack the Imperials in the rear.[31] With this plan Görgei hoped to occupy all the Austrian siege fortifications and the surrounding heights, and after the arrival of the remaining infantry units, cavalry and artillery of I and III Corps, then to start a general attack supported by VII Corps, and to push the Imperials towards Győr, while VII Corps was to remain in reserve.[21]

In the meantime on 21 April Lieutenant General Balthasar von Simunich wrote to Lieutenant General Anton Csorich, that Görgei had entered Komárom that day, and that an attack on the Imperial besieging forces on the southern bank of the Danube was imminent. He therefore asked his colleague to send him cavalry and artillery reinforcements.[19] On the 24th he informed Csorich that the Hungarians had reconstructed the bridge across the Danube, and had started to cross the river on it and on rafts. He asked Csorich to bring his troops to Herkálypuszta by the morning of 25 April at the latest, to help him against the Hungarian attack.[22]

In accordance with Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden's orders as outlined above, the Imperial troops completed their evacuation of Pest on 23 April, whereupon General Lajos Aulich and his Hungarian II Corps entered the city on 25 April. Welden ordered Major General Franz Wyss to move his brigade to Tata, Major General Franz de Paula Gundaccar II von Colloredo-Mannsfeld to have his brigade retreat from Esztergom to Dorog, and Schwarzenberg's division to move from Buda to Esztergom, thus withdrawing all Austrian troops from the region of the Danube Bend (except the garrison of Buda under Major General Heinrich Hentzi) and concentrating them around and near Komárom, to be available in the event of a battle at Komárom.[23] Welden had finally understood that the Hungarian forces east of Pest (Aulich's II Corps) were not so overwhelming as to be a real threat to the imperials if they retreated from their secure positions in Pest and the Danube Bend towards Komárom.[24] This is why they could concentrate around Komárom, to resist the main Hungarian force preparing to attack them there. But Görgei hoped that his deception plan was still working, which is why he ordered the crossing of the Danube to attack the Austrians concentrated there, hoping to use his supposed numerical superiority to destroy them, and thereby to encircle those forces which he thought were still in the Danube Bend.[25] He was warned by his chief of general staff Colonel József Bayer, among others, that crossing south of the Danube was a very risky plan, but Görgei would not change his mind.[23]

Opposing forces

The Hungarian army

Left wing

Major General György Klapka

I. corps;

1. division;[lower-alpha 1]

- Dipold brigade: 6. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 782 soldiers), 26. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 668 soldiers), 52. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 645 soldiers), 6. six-pounder cavalry battery (160 soldiers, 120 horses, 8 cannons) = 2255 soldiers, 120 horses, 8 cannons;

- Bobich brigade: 28. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 820 soldiers), 44. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 930 soldiers), 47. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 840 soldiers), 1. six-pounder cavalry battery (64 soldiers, 107 horses, 8 cannons) = 2654 soldiers, 107 horses, 8 cannons;

2. division;

- Artillery of the division: 1/2 twelve-pounder battery (87 soldiers, 60 horses, 4 cannons), 4. six-pounder infantry battery (74 soldiers, 108 horses, 8 cannons) = 161 soldiers, 168 horses, 12 cannons;

- Cavalry led by Major General József Nagysándor: Colonel and 1. Major class of the 8. (Coburg) Hussar Regiment (4 companies: 442 soldiers, 442 horses).

III. corps

- Cavalry: 2 (Hannover) Hussar Regiment (4 companies: 440 soldiers, 440 horses), 3 (Ferdinand d'Este) Hussar Regiment (3 companies: 352 soldiers, 352 horses), Polish uhlans (1 company: 82 soldiers, 82 horses), 3. six-pounder cavalry battery (123 soldiers, 96 horses, 6 cannons) = 1399 soldiers, 1372 horses, 6 cannons;

Center

Major General János Damjanich

I. corps;

2. Kazinczy division;

- Bátori-Sulcz brigade: 19. Honvéd battalion (4 companies: 226 soldiers), sappers (2 companies: 206 soldiers) = 432 soldiers;

- Zákó brigade: 34. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 790 soldiers);

III. corps;

1. (Knezić) division;

- Kiss brigade: 9. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 738 soldiers), 1. battalion of the 34. (Prince of Prussia) infantry regiment (4 companies: 401 soldiers), 3. battalion of the 34. (Prince of Prussia) infantry regiment (6 companies: 636 soldiers), 5. six-pounder cavalry battery (153 soldiers, 117 horses, 8 cannons) = 1928 soldiers, 117 horses, 8 cannons;

- Kökényesi brigade: 3. battalion of the 52. (Franz Karl) infantry regiment (6 companies: 795 soldiers), 65. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 837 soldiers), Selmec jägers (1 company: 93 soldiers), sappers (4 companies: 376 soldiers),1/2 Congreve rocket battery (36 soldiers, 12 horses, 2 rocket launching racks) = 2137 soldiers, 12 horses, 2 rocket launching racks;

2. (Wysocki) division;

- Czillich brigade: 3. battalion of the 60. (Wasa) infantry regiment (6 companies: 701 soldiers), 42. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 649 soldiers), Polish Legion (6 companies: 510 soldiers), 4. six-pounder infantry battery (151 soldiers, 108 horses, 8 cannons) = 2011 soldiers, 108 horses, 8 cannons;

- Leiningen brigade: 3. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 865 soldiers), 19. battalion of the 60. (Schwarzenberg) infantry regiment (6 companies: 651 soldiers), 7. six-pounder infantry battery (118 soldiers, 73 horses, 6 cannons) = 1634 soldiers, 73 horses, 6 cannons;

Detached units of the VIII. corps

Major General Richard Guyon: 64. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 1022 soldiers), 57. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 1208 soldiers) = 2230 soldiers;

Right wing

Major General Artúr Görgei

I. corps;

2. Kazinczy division;

- Bátori-Sulcz brigade: 17. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 844 soldiers), sappers (2 companies: 206 soldiers), 3. battalion of the 39. infantry regiment (6 companies: 580 soldiers), 1. twelve-pounder 1/2 battery (87 soldiers, 60 horses, 4 cannons) = 1511 soldiers, 60 horses, 4 cannons;

- Cavalry: 1 (Imperial) Hussar Regiment (8 companies: 840 soldiers, 840 horses), unknown Hussar Regiment (1/2 companies: ? soldiers, ? horses), Polish uhlans (1 company: 82 soldiers, 82 horses), unknown half battery from the I. corps (? soldiers, ? horses, 3-4 cannons) = 2351+? soldiers, 900+? horses, 7-8 cannons;

Detached units of the VIII. corps

Major General Richard Guyon: 70. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 1045 soldiers), 71. Honvéd battalion (6 companies: 974 soldiers) = 2019 soldiers;

Units of unknown dislocation

Cavalry of the I. corps: 13 (Hunyadi) Hussar Regiment (2 companies: 212 soldiers, 212 horses), 14 (Lehel) Hussar Regiment (2 companies: 168 soldiers, 168 horses) = 280 soldiers, 380 horses;

Cavalry of the III. corps: 2 (Hannover) Hussar Regiment (4 companies: 400 soldiers, 400 horses), 3 (Ferdinand d'Este) Hussar Regiment (1 company: 117 soldiers, 117 horses) = 517 soldiers, 517 horses;

Disposition:

Left flank: 36 infantry companies, 12 cavalry companies, 30 cannons = 6469-? soldiers, 1276 horses with saddles, 491-? horses for wagon or cannon traction, 30 cannons;

Center: 75 infantry companies, 24 cannons = 11162 soldiers, 310 horses for wagon or cannon traction, 24 cannons;

Right flank: 24 infantry companies, 8 1/2 cavalry companies, 8 cannons = 4370+? soldiers, 840+? horses with saddles, 60 horses for wagon or cannon traction, 8 cannons;

Units of unknown dislocation: , 10 1/2 cavalry companies = 897-? soldiers, 897 horses with saddles.

Total: 22,898 soldiers, 3013 horses with saddles, 861 horses for wagon or cannon traction, 62 cannons. [26]

The Austrian army

I. corps

- 85 infantry battalions, 22 cavalry companies = 13,489 soldiers, 2997 horses, 54 cannons;

II. corps;

- 77 infantry battalions, 19 cavalry companies = 12,088 soldiers, 2709 horses, 45 cannons;

III. corps;

- Lederer division: 44 infantry battalions, 2 cavalry companies = 7910 soldiers, 322 horses, 9 cannons;

Total: 33,487 soldiers, 3013 horses with saddles, 6028 horses for wagon or cannon traction, 108 cannons.[2]

Battle

During the night of 25/26 April, at 2 o'clock[21] in the morning, the Hungarian I, III, and VIII corps (this latter being the garrison of the fortress) crossed the Danube on the raft bridge they had constructed and launched a dawn attack against the enemy entrenchments around the fortress on the south bank of the river.[27] First the Knezić division of the III. corps and the Zákó brigade of the I. corps crossed the Danube on the raft bridge (made a few days earlier) in the Star Trench (Csillagsánc), then the Kiss brigade occupied the trenches nr. 7. and 8. close to Nagyigmánd. Then General Knezić sent 34. Honvéd battalion of the Zákó brigade and a part of the 3. battalion of the 52. infantry regiment, from his division, to reinforce the Kiss brigade.[28] The Wysocki division, which arrived now on the battlefield became the center of the Hungarian order of battle. On the left wing, the Dipold and Bobich brigades crossed at 5:00 a.m. the Danube and attacked Ószőny.[29] The cavalry brigade led by General Nagysándor, reinforced by four companies of the 8. Hussar Regiment, belonging to the I. corps, was sent by General Damjanich towards Ószőny, to ensure contact with the troops from the Hungarian left wing.[28]

After occupying the 7. and 8. trenches, Kiss's brigade turned west, and occupied Monostor (in German Sandberg), probably together with the trenches nr. 4., 5., 6.,[28] capturing the enemy siege artillery, destroying the Hohenlohe battalion which was defending it, and capturing 4 officers and 350 men.[30] However, after this, the Austrian 2. jäger battalion attacked the Kiss brigade, recapturing the trenches, but the Honvéd battalions, coming from the Hadi-Island (today Erzsébet sziget/Alžbetin Ostrov/Elisabeth island on the Southern part of the city, today part of Slovakia), led by General Richard Guyon,[lower-alpha 2]

attacked them from the flank, and returned the Monostor trenches to the Hungarians.[32] Hearing the sound of harsh clashes from the direction of Monostor, Knezić sent the 19. Honvéd battalion of the Zákó brigade to occupy Újszőny. The Honvéd battalion in question, occupied, in a heavy fight, Monostor, together with one of the trenches nr. 9. or the 10.[lower-alpha 3] The Sulcz and the Zákó brigades (which formed the Kazinczy division) remained behind to defend the newly occupied trenches and to support the right wing. The soldiers of the 34. Honvéd battalion installed themselves in the trenches nr. 7 and 8, the 19. Honvéd battalion the 9. or the 10., while the right wing was reinforced by the 17. Honvéd battalion, the 3. battalion of the 39. infantry regiment and two sapper companies of the Bátori-Sulcz brigade.[29] Klapka detached an infantry battery and a twelve-pounder battery of the Kazinczy division, and sent them to reinforce the flanks of the army. The infantry battery and half of the twelve-pounder battery were sent to the left flank, while the other half of the latter to the right flank.[29]

Lederer's Imperial brigade conducted a fighting withdrawal to allow the heavy siege artillery and ammunition stock to retreat behind the Concó creek.[20] After being pushed out of the trenches, the Austrian brigade retreated to the heights south of Monostor, where, reinforced by the 2. jäger battalion and other reinforcements, they tried to hold this position, but then they retreated behind the Concó creek, trying to establish here a strong defensive position.[20]

On the left wing, the attack of the Dipold brigade against Ószőny started a little later than it was planned: the day began to dawn. Thanks to this, the Austrian Liebler brigade noticed this and retreated toward Mocsa, but its rearguard, formed by two Deutschmeister companies, after being cut from the rest of the brigade by two Hungarian Coburg hussar companies, they surrendered without a fight.[20]

At 6 o'clock, the commander-in-chief Hungarian army, General Artúr Görgei arrived on the battlefield and ordered his troops to continue the advance. He commanded the right wing advancing in the Ács, forest, while the left wing led by General György Klapka advanced between Mocsa and Ószőny.[34] Sensing that the Honvéd battalions under the command of General Knezić, which were fighting for the trenches southwest from Komárom, were the most exposed to the enemy's attacks, and knowing that because of the Austrian siege fortifications for which they fought, made impossible the use of artillery and cavalry, Görgei went, with half of a battery and half of a Hussar company, diverted from the troops which were still crossing the bridges and marching towards the battlefield, towards Monostor.[35] From Monostor, Görgei sent the half battery and the half Hussar company towards Ács, to divert the enemy's attention, which was pressuring the Hungarian center, towards the right flank.[35] Then he sent the 17. Honvéd battalion and the 3. battalion of the 39. infantry regiment from the Bátori-Sulcz brigade to take a position in the trenches of Monostor. Then he sent two companies of the 17. Honvéd battalion in the vineyards beyond Monostor, and when they were attacked by Austrian troops, he sent another two companies to support them.[35] These companies successfully repulsed the enemy attacks until, they run out of bullets, so Görgey called them back inside the trenches, where they replenished their ammunition, then he sent them back in the vineyard.[35] Shortly, the 8 companies of the I. Hussar regiment's 8 companies and a half battery led by colonel István Mesterházy, and two battalions of the VIII. corps (probably the 70. and 71 battalions) arrived, and thanks to this Görgei saw the chance to advance, with their help, to the main road leading to Ács, and to threaten the Austrian's retreat route.[35] Now with the four Honvéd battalions, the hussar regiment, and the two half batteries at his disposal, Görgei led the attack against the Ács woods: the northern section was stormed by the 17. Honvéd battalion, against the southern section, were sent the 70. and 71. Honvéd battalions, and east to this the cavalry and the two half batteries pushed forward against the Austrian cavalry, while the 3. battalion of the 39. infantry regiment represented the reserve under Görgei's personal command.[36]

At this point, Simunich was on the verge of suffering a heavy defeat, but he was saved by the intervention of the Imperial II Corps and then the III Corps. These had retreated from Buda and Pest,[34] as ordered by Welden five days before, after the battle of Nagysalló. Until the arrival of the III. corps the Hungarian and the imperial forces had been roughly equal (around 14,000 troops of the Hungarian I and III Corps against similar numbers from Simunich's besieging army),[37] but the addition of Schlik's III Corps created a 2:1 superiority for the Austrians.[38]

At this moment the situation was as follows: on the right wing the Hungarian Kiss brigade, reinforced by the 70. and 71. battalions from the VIII. corps was advancing towards the Ács wood[20] faced the Lederer brigade under the command of Lieutenant General Balthasar von Simunich; in the center, on the heights south and southeast of the Monostor trenches the Bátori-Sulcz brigade, face to face with the bulk of the II. and III. Austrian corps; behind the Kiss and Bátori-Sulcz stood the Kökényessy brigade; on the left wing along the road to Mocsa, stretching to Ószőny was the Dipold brigade facing the Austrian Liebler brigade. The bulk of the Hungarian cavalry, led by General Nagysándor, was on the second line behind the center, four of its companies helping the Dipold brigade. The Austrian Montenuovo cavalry brigade was heading from Kocs to Mocsa towards Nagysándor's hussars. The rest of Klapka's and Damjanich's corps, together with a part of the VIII. corps was waiting at the Danube bridgehead, while the VII. corps was heading towards Komárom from the northwest, on the left bank of the Danube, but they will not arrive until the end of the battle.[20] At this moment Görgei, to continue his successful advance towards Ács, summoned those troops from the Danube bridgehead, which were not used by Damjanich, depriving the left wing under Klapka, who had only one brigade (Dipold brigade) at his disposal, of any reinforcements.[20]

After Klapka's troops, covered by the fortress artillery, had advanced to Ószőny, pushing back Liebler's brigade, but the latter, waiting until the fire of his artillery caused the Hungarians to stop,[20] then, with the help of Franz Schlik’s cavalry, launched a counterattack.[34] This made the Hungarians retreat in the so-called Star Fort of Komárom, but when it came within range of the Hungarian guns from the fortress of Komárom, the cannonade from these caused heavy losses to the Liebler brigade, forcing it to fall back to its initial position.[34] Liebler's brigade's retreat was pursued towards Nagyigmánd by two regiments of Hungarian hussars led by Major General József Nagysándor, supported by the 47th Honvéd battalion and a 12-pounder battery.[34]

Schlik, the commander of III Corps, the senior commander, took overall command of the Imperial army, and at noon he ordered a general attack.[34] His plan was not to take back the Austrian trenches and to push back the Hungarians back in their starting positions behind the walls of Komárom, but to ease the retreat of the siege corps, together with their siege equipment towards Vienna.[20]

On the left wing, Nagysándor's 16 hussar companies and the uhlans of the Polish Legion companies, which pursued the Liebler brigade, advanced on the Ószőny-Nagyigmánd road, wanting to attack Schlik's troops from the right and back.[20] Schlik sent against them the concentrated cavalry of Lieutenant General Franz Liechtenstein, the Nicholas dragoons, and the Civalart uhlans, supported by a Congreve rocket battery. The two cavalry masses clashed southeast from the Csém grange.[20] In the first attack participated from the Austrian side, the Kisslinger dragoon brigade and the rocket battery, while from the Hungarian side the 2. and 3. hussar regiments and the Polish uhlans, at the end of which the hussars, also attacked by the cannons of the Austrian artillery, were forced to retreat. Now the second line of the Hungarian cavalry, represented by the 3. Hussar regiment, led by Colonel Kászonyi, intending to stop at least the pursuit of the Kisslinger brigade, charged, being joined also by the hussars of the first line, which earlier retreated, but now regrouped themselves along the Mocsa-Ács road, but at this moment the Austrian Montenuovo cavalry brigade appeared from the direction of Mocsa, and attacked with the greatest vigor the hussars on their right flank, causing them to rout.[20] The Austrian cavalry then attacked the 47. Honvéd battalion, scattering them, almost capturing the twelve-pounder battery. Luckily the 26. Honvéd battalion led by Major Beöthy came to their rescue, first firing several times, then carrying out a bayonet charge against the enemy cavalry, saving the 47. Honvéd battalion from their hopeless situation, and when Klapka ordered the Hungarian cannoneers near to them to shoot in the Austrian cavalry, Kisslinger was forced to retreat his order a retreat to his tired riders.[20]

With this the Hungarians managed to halt the powerful imperial advance on their left wing, so the battle here continued as an artillery duel until they ran out of cannonballs.[39] One of the adjutants of the Hungarian headquarters, Kálmán Rochlitz, wrote in his memoirs: "Our field artillery ran out of ammunition so that when I went to one of the batteries of I corps, I saw with my own eyes how our artillerymen picked up from the ground the cannon balls fired at us [by the enemy], wadded them with rags made of clothes ripped from the dead bodies of the fallen [soldiers], and in this way, they loaded them into the gun barrels on top of the loose gunpowder they had put in first [in the cannon tubes]."[40]

In the center, no serious combats happened until the two Austrian corps arrived from the direction of Buda. The cause of this was that Damjanich, after agreeing with Görgei, to advance, with a part of the troops from the Danube bridgehead to reinforce the Bátori-Sulcz brigade, faced in front of him, a terrain, which was very accidented and filled with the siege trenches of the Austrians, which made the advance of the cavalry and artillery almost impossible, so, to enable this, they had to be filled with earth.[20] When Damjanich, around 9:00 a.m., finally arrived on the battlefield, he saw in front of him, between Herkály and Csém, the newly arrived Austrian troops under the leadership of General Schlik, fully deployed, and ready for the battle.[20] And when Damjanich started the deployment of his troops, the Austrian artillery unleashed a harsh cannonade against the Hungarians, causing them losses and difficulties.[20] But when the Hungarians finished their deployment, they managed to stabilize the situation,[20] although the center under Damjanich's command was attacked from two sides by the numerically superior imperial II and III Corps.[41] The fight in the center continued as an artillery duel.[20]

According to Schlik's orders, Simunich ordered Lederer to advance again in the Ács woods, and attack Görgei's 4 battalions and 10 cavalry companies.[20] Because he did not expect any serious attack from the direction of Ács, Görgei sent only a few units to hold the Ács forest, deploying the bulk of his troops on the heights southeast to the forest.[20] When the Lederer brigade entered again in the forest, the Hungarian units were pushed out of it, so Görgei sent the 9., 17., 19, and 65 Honvéd battalions, together with the 3. battalions of the 19. and 60. infantry regiments, to recapture the forest, but although they achieved temporary successes, they had to retreat because they were not enough coordinated.[20]

On the right wing, during another attack of the troops of Görgei, when they approached the Ács forest at 600-750 paces, he received a report from Damjanich, who commanded the center, that Simunich's corps received considerable reinforcements, the cavalry under Nagysándor was pushed back, and Klapka retreats on the left flank, so he understood that he has no other choice, but to start the retreat gradually towards the Monostor trenches, and to hold them at all cost.[36] Görgei also started to feel the Austrian pressure in the substantial increase of the Austrian artillery shootings, right at the moment when 6 of his 8 batteries run out of ammunition.[36] Görgei's battalions in the Ács forest were subjected to ever-increasing pressure from the ever-increasing number of imperials, who appeared in this place in greater and greater numbers because General Franz Schlik had already given the order to retreat to the west after the battle, preventing the Hungarian commander from achieving success here.[34] Being informed that the Austrian center started to push the severely outnumbered Damjanich with its infantry and also because of the VII. corps did not arrive on the battlefield, around 1:00 p.m., Görgei decided to give the order to all his troops to retreat behind the imperial siege trenches around Komárom, captured by his troops at the beginning of the battle, and wait for reinforcements.[41] Schlik, after achieving his purpose to secure the retreat of the Simunich siege corps and a part of its artillery and ammunition (as mentioned earlier, the Hungarians captured 7 siege mortars), ordered to his infantry and cavalry to pull back, and continued an artillery duel with the Hungarians until 3:00 p.m., when the ammunition ended on both sides, then started the march towards the western border of Hungary.[20]

So the battle effectively ended at 1 p.m.[41] At sunrise Görgei had sent an order which was reiterated at 9 o'clock by his chief of staff Colonel József Bayer to Lieutenant-Colonel Ernő Poeltenberg, (the new commander of VII corps, in place of General András Gáspár, who had gone on leave not long before) to come quickly to Komárom from where VII Corps was stationed at Perbete Perbete.[40] Poeltenberg came as fast as he could, but his troops’ movements were slowed by the fact that the roads were flooded because of the spring rains, and when they reached the north bank of the Danube, the raft bridge improvised by Görgei's sappers had almost collapsed and had to be strengthened before they could finish crossing to the south bank.[41] So Poeltenberg's two Hussar regiments and cavalry batteries only reached the battlefield at 3 o'clock when the battle was already over,[41] while the infantry divisions did not arrive until evening. They set off that night towards Győr, to pursue the enemy and to occupy that very important city.[38]

After the arrival of Schlik's III Corps, Görgei, who before the battle had thought that his army would only face Simunich's siege corps, now expected the whole imperial main army to attack him. He, therefore, decided to face the foe from within the siege trenches with the fortress behind him, the latter still having enough ammunition (while his field artillery and the captured siege artillery had run out, as mentioned above), with which he hoped to withstand such a powerful attack.[40] He did not know that Welden had sent Jelačić's corps to southern Hungary[38] to help the Serbian insurgents, Austrian allies who were in a grave situation after the victories of the Hungarian armies led by Mór Perczel and Józef Bem,[19] and had sent II Corps to Sopron through Veszprém and Pápa.[38]

The imperial army used its final attack only to pin the Hungarians to cover their withdrawal towards Pozsony and Vienna and avoid heavy losses during their retreat. The Hungarian hussars still pursued, but on their tired horses were unable to achieve any significant result.[41] Schlik ordered the imperial troops to move towards Győr from Ács along the road which they had secured during the battle, to arrive near the border safely.[42] Besides their casualties in dead, wounded and prisoners, they lost 7 siege cannons and mortars, a huge amount of food and ammunition, and all of their tentage.[43]

The outcome of the battle

In the 21st volume of József Bánlaky's monumental Military History of the Hungarian Nation (A magyar nemzet hadtörténete), although he does not make an explicit judgement about the result of the battle, by quoting Görgei's report to the Hungarian government in which the Hungarian commander calls a victory, albeit without comment, Bánlaky's tacitly accepts Görgei's opinion.[20] In his book about Görgei's military career, László Pusztaszeri speaks about the "failure to achieve a decisive victory",[38] showing that he tends to regards this battle as a victory but not a decisive one. In an article in the Hungarian historical magazine Rubicon, Tamás Tarján also considers this battle a Hungarian victory.[44] Róbert Hermann's opinion is that, although the Hungarian army accomplishing its immediate tactical purpose of relieving the very important fortress, the Battle of Komárom on 26 April 1849 can be viewed rather as an indecisive battle, because the imperial plan beforehand was to abandon the siege anyway and to retreat towards Pozsony and Vienna; thus the Hungarians did not impose their will on the enemy, but just forced them to retreat a few days earlier than planned.[41] The Hungarian plan to surround and destroy the imperial force failed because of the arrival and attack of Schlik's III Corps. But the loss of much of the siege artillery, and of a whole grenadier division,[41] a huge amount of food, ammunition, 7 heavy siege cannons and mortars, and the whole military tent camp, all captured by the Hungarians, was a hard blow for the imperial commanders.[43]

Aftermath

The first Battle of Komárom practically ended the Spring Campaign, achieving its main purposes: the relief of Komárom and the expulsion from Hungary of the main imperial armies.[45] The major success of the royal-imperial Austrian army was that it was able to retreat to the Rába river, close to the western border of Hungary, without being surrounded by Görgei's army, and without taking heavy losses.[45]

The Hungarian National Defense Committee was the interim government of Hungary, created after the free Hungarian government led by Lajos Batthyány, resigned on 2 October 1848. The emperor and King of Hungary, Ferdinand I of Austria) had refused to recognize the new government. As a response to the Olmütz of 4 March 1849, which abolished the Hungarian Constitution, and to the April laws, which deposed Hungary from all of its liberties and degraded it to a simple Austrian province, and seeing the great victories of the Hungarian National Army as an opportunity to respond to the Austrian constitution, on 14 April 1849 Hungary declared its total independence from the Habsburg Empire,[46] As a result of this declaration of independence, on 2 May the new Hungarian Government was established under the leadership of Bertalan Szemere, in which Görgei became Minister of War, and his election was of course a consequence of his victories on the battlefield.[45]

After the relief of Komárom from the imperial siege, and the retreat of the Habsburg forces to the Hungarian border, the Hungarian army had two choices as to where to continue its advance.[47] One was to march on Pozsony and Vienna, in order to finally force the enemy to fight on his own ground; the other was to return eastwards and take Buda Castle which was held by a strong imperial garrison of 5,000 men commanded by Heinrich Hentzi. Although the first choice seemed very attractive, it would have been nearly impossible for it to succeed. While the Hungarian army gathered before Komárom had fewer than 27,000 soldiers, the imperial army waiting for them around Pozsony and Vienna was more than 50,000 strong, so it was twice the size of Görgei's force. Furthermore, the Hungarian army was short of ammunition.[47] On the other hand, capturing Buda castle seemed more achievable at that moment, and besides it was also very important in many respects. It could be achieved with the available Hungarian forces; a strong imperial garrison in the middle of the country represented a serious threat if the main Hungarian army wanted to move towards Vienna, because attacks from the castle could have cut the Hungarian supply lines, so it needed to be besieged by a significant force in order to prevent such sorties; furthermore, the presence of Jelačić's corps in southern Hungary made the Hungarian commanders think that the Croatian ban could advance towards Buda at any moment to relieve it, cutting Hungary in two.[47] So the Hungarian staff understood that without taking the Buda Castle, the main army could not conduct a campaign towards Vienna without putting the country in grave danger. Beside the military arguments in favor of the siege of Buda, there were political ones as well. After the declaration of the independence of Hungary, the Hungarian parliament wanted to convince foreign states to acknowledge Hungary's independence, and knew there was more chance of achieving this after total liberation of their capital city, Buda-Pest; and the capital city also included Buda castle.[47] So the council of war held on 29 April 1849 decided to besiege Buda Castle, and only after the arrival of Hungarian reinforcements from southern Hungary would they start an offensive against Vienna to force the empire to sue for peace and to recognize the independence of Hungary.[47]

From an imperial officer captured in the battle, Görgei learned that the intervention of the Russian army against the Hungarian revolution was imminent.[48] The Austrian government, seeing that they could not crush the Hungarian revolution by themselves with only their allies from among the nationalities within Hungary, decided to start discussions with the tsar about a Russian intervention at the end of March. The official Austrian request for intervention was then sent on 21 April.[49] The Austrian government asked only for a few tens of thousands of Russian troops under imperial leadership, but Tzar Nicholas I of Russia decided to send 200,000 soldiers, and to hold another 80,000 in readiness to enter Hungary if needed. This meant that he was prepared to send one quarter of Russia's military power to Hungary.[49] This huge army, together with the 170,000 soldiers of the Habsburgs, and the several tens of thousands of Serbian, Romanian and Croatian nationality troops fighting against only 170,000 Hungarian soldiers, represented an invincible force[49] So amidst the joy at the liberation of much of Hungary, and after the victories of the Spring Campaign, the Hungarians began to feel concerned about the imminent Russian attack.

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The division here has no leader, because its commander, Colonel Károly Knezić led the rest of the division on the center.

- ↑ Historian Róbert Hermann argues that Guyon did not participate in this battle, and Klapka in whose memoirs he is presented as the leader of this attack, is wrong.[31]

- ↑ Historian Róbert Hermann mentions that it is not very clear which trench was occupied by the Honvéd battalion led by Major János Nyeregjártó, and it could be also the trench nr. 10.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), pp. 1000-1001

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann 2004, pp. 252.

- 1 2 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, p. 270.

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2001, p. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, p. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 233–236.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, p. 284.

- 1 2 Hermann 2001, p. 285.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, p. 290.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, p. 287.

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2004, p. 243.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, p. 301.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, p. 291.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 289.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 290.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hermann 2001, pp. 291.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Bánlaky József: A magyar nemzet hadtörténete XXI, A komáromi csata (1849. április 26-án) Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. 2001

- 1 2 3 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 330.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 291–292.

- 1 2 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 329.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 328–329.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 326–329.

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), pp. 998-1002

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 248.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), p. 987

- 1 2 3 Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), p. 988

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), pp. 988-989

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), p. 989

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), pp. 987-988

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hermann 2004, pp. 249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), p. 991

- 1 2 3 Hermann Róbert: A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4), p. 992

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 331.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 334.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 332.

- 1 2 3 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 333.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hermann 2004, pp. 250.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 334–335.

- 1 2 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 335.

- ↑ Tarján Tamás, 1849. április 26. A komáromi csata, Rubicon

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2001, pp. 295.

- ↑ Hermann 1996, pp. 306–307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hermann 2013, pp. 27.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 337.

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2013, pp. 43.

Sources

- Hermann, Róbert, ed. (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története ("The history of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont Kiadó. p. 464. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Bánlaky, József (2001). A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme ("The Military History of the Hungarian Nation) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Arcanum Adatbázis.

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 ("Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Independence 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. p. 430. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc hadtörténete ("Military History of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. p. 424. ISBN 963-9376-21-3.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2010), "A magyar hadsereg az 1849. április 26-i komáromi csatában" (PDF), Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 2010 (volume 123, nr. 4) (in Hungarian)

- Hermann, Róbert (2013). Nagy csaták. 16. A magyar függetlenségi háború ("Great Battles. 16. The Hungarian Freedom War") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Duna Könyvklub. p. 88. ISBN 978-615-5129-00-1.

- Pusztaszeri, László (1984). Görgey Artúr a szabadságharcban ("Artúr Görgey in the War of Independence") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. p. 784. ISBN 963-14-0194-4.

- Tarján, Tamás, "1849. április 26. A komáromi csata", Rubicon