The flyback converter is used in both AC/DC, and DC/DC conversion with galvanic isolation between the input and any outputs. The flyback converter is a buck-boost converter with the inductor split to form a transformer, so that the voltage ratios are multiplied with an additional advantage of isolation. When driving, for example, a plasma lamp or a voltage multiplier, the rectifying diode of the boost converter is left out and the device is called a flyback transformer.

Structure and principle

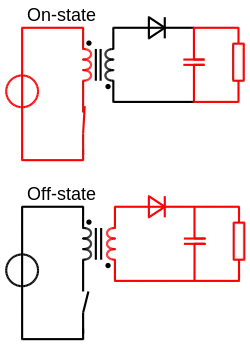

The schematic of a flyback converter can be seen in Fig. 1. It is equivalent to that of a buck-boost converter,[1] with the inductor split to form a transformer. Therefore, the operating principle of both converters is very similar:

- When the switch is closed (top of Fig. 2), the primary of the transformer is directly connected to the input voltage source. The primary current and magnetic flux in the transformer increases, storing energy in the transformer. The voltage induced in the secondary winding is negative, so the diode is reverse-biased (i.e., blocked). The output capacitor supplies energy to the output load.

- When the switch is opened (bottom of Fig. 2), the primary current and magnetic flux drops. The secondary voltage is positive, forward-biasing the diode, allowing charge carriers to flow from the transformer. The energy from the transformer core recharges the capacitor and supplies the load.

The operation of storing energy in the transformer before transferring to the output of the converter allows the topology to easily generate multiple outputs with little additional circuitry, although the output voltages have to be able to match each other through the turns ratio. Also there is a need for a controlling rail which has to be loaded before load is applied to the uncontrolled rails, this is to allow the PWM to open up and supply enough energy to the transformer.

Operations

The flyback converter is an isolated power converter. The two prevailing control schemes are voltage mode control and current mode control. In the majority of cases current mode control needs to be dominant for stability during operation. Both modes require a signal related to the output voltage. There are three common ways to generate this voltage:

1. Use an optocoupler on the secondary circuitry to send a signal to the controller.

2. Wind a separate winding on the coil and rely on the cross regulation of the design.

3. Sample the voltage amplitude on the primary side, during the discharge, referenced to the standing primary DC voltage.

The first technique, involving an optocoupler, has been used to obtain tight voltage and current regulation, whereas the second approach has been developed for cost-sensitive applications where the output does not need to be as tightly controlled, but many components including the optocoupler can be eliminated from the overall design. Also, in applications where reliability is critical, optocouplers can be detrimental to the system's MTBF (Mean Time Between Failure). The third technique, primary-side sensing, can be as accurate as the first and more economical than the second, yet requires a minimum load so that the discharge-event keeps occurring, providing the opportunities to sample the 1:N secondary voltage at the primary winding (during Tdischarge, as per Fig 3).

A variation in primary-side sensing technology is where the output voltage and current are regulated by monitoring the waveforms in the auxiliary winding used to power the control IC itself, which have improved the accuracy of both voltage and current regulation. The auxiliary primary winding is used in the same discharge phase as the remaining secondaries, but it builds a rectified voltage referenced commonly with the primary DC, hence considered on the primary side.

Previously, a measurement was taken across the whole of the flyback waveform which led to error, but it was realized that measurements at the so-called knee point (when the secondary current is zero, see Fig. 3) allow for a much more accurate measurement of the secondary side behavior. This topology is now replacing ringing choke converters (RCCs) in applications such as mobile phone chargers.

Limitations

Continuous mode has the following disadvantages, which complicate the control of the converter:

- The voltage feedback loop requires a lower bandwidth due to a right half plane zero in the response of the converter.

- The current feedback loop used in current mode control needs slope compensation in cases where the duty cycle is above 50%.

- The power switches are now turning on with positive current flow - this means that in addition to turn-off speed, the switch turn-on speed is also important for efficiency and reducing waste heat in the switching element. Active Clamp Flyback[2] is a technology that alleviates this limitation.

Discontinuous mode has the following disadvantages, which limit the efficiency of the converter:

- High RMS and peak currents in the design

- High flux excursions in the inductor

Applications

- Low-power switch-mode power supplies (cell phone charger, standby power supply in PCs)

- Low-cost multiple-output power supplies (e.g., main PC supplies <250 W ) The flyback converter is commonly used at the 50 to 100 W power range, as well as in highvoltage power supplies for televisions and computer monitors - Fundamentals of Power Electronics, Erickson & Maksimovic .

- High voltage supply for the CRT in TVs and monitors (the flyback converter is often combined with the horizontal deflection drive)

- High voltage generation (e.g., for xenon flash lamps, lasers, copiers, etc.)

- Isolated gate driver

See also

- Forward converter

- Joule thief - Minimalist switchmode converter example

References

- Billings, Keith (1999), Switchmode Power Supply Handbook (Second ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-006719-8

- ↑ The Flyback Converter - Lecture notes - ECEN4517 - Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering - University of Colorado, Boulder.

- ↑ "What Is Active Clamp Flyback". Silanna Semiconductor. 11 May 2021.