| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

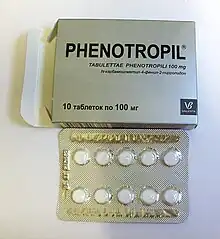

| Trade names | Phenotropil; Carphedon |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets) |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% |

| Metabolism | None |

| Onset of action | 20-40 minutes |

| Elimination half-life | 3–5 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (~40%), bile and perspiration (~60%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.214.874 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

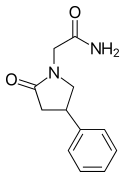

| Formula | C12H14N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 218.256 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Boiling point | 486.4 °C (907.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Phenylpiracetam (INN: fonturacetam,[1] brand names Phenotropil Фенотропил, Carphedon), is a phenylated analog of the drug piracetam. It was developed in 1983 as a medication for Soviet Cosmonauts to treat the prolonged stresses of working in space. Phenylpiracetam was created at the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Biomedical Problems in an effort led by psychopharmacologist Valentina Ivanovna Akhapkina (Валентина Ивановна Ахапкина).[2] In Russia it is now available as a prescription drug. Research on animals has indicated that phenylpiracetam may have anti-amnesic, antidepressant, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and memory enhancement effects.[3][4]

Human research

Phenylpiracetam is typically prescribed as a general stimulant or to increase tolerance to extreme temperatures and stress.[5]

A few small clinical studies have shown possible links between prescription of phenylpiracetam and improvement in a number of encephalopathic conditions, including lesions of cerebral blood pathways, traumatic brain injury and certain types of glioma.[6]

Phenylpiracetam has been researched for the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[7]

Clinical trials were conducted at the Serbsky State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. The Serbsky Center, Moscow Institute of Psychiatry, and Russian Center of Vegetative Pathology are reported to have confirmed the effectiveness of Phenylpiracetam(Phenytropil) describing the following effects: improvement of regional blood flow in ischemic regions of the brain, reduction of depressive and anxiety disorders, increase the resistance of brain tissue to hypoxia and toxic effects, improving concentration and mental activity, a psychoactivating(sic) effect, increase in the threshold of pain sensitivity, improvement in the quality of sleep, and an anticonvulsant action, though with the side effect of an anorexic effect in extended use.[2]

Animal Model Research

Phenylpiracetam has been shown to reverse the depressant effects of the benzodiazepine diazepam, increases operant behavior, inhibits post-rotational nystagmus, prevents retrograde amnesia, and has anticonvulsant properties in animal models.[3][8][9]

In Wistar rats with gravitational cerebral ischemia, Phenylpiracetam reduced the extent of neuralgic deficiency manifestations, retained the locomotor, research, and memory functions, increased the survival rate, and lead to the favoring of local cerebral flow restoration upon the occlusion of carotid arteries to a greater extent than did piracetam.[10]

Operant behavior

In tests against a control, Sprague-Dawley rats given free access to less-preferred rat chow and trained to operate a lever repeatedly to obtain preferred rat chow performed additional work when given methylphenidate, d-amphetamine, and phenylpiracetam. Rats administered 100 mg/kg phenylpiracetam performed, on average, 375% more work than rats given placebo, and consumed little non-preferred rat chow. In comparison, rats administered 1mg/kg d-amphetamine or 10 mg/kg methylphenidate performed, on average, 150% and 170% more work respectively, and consumed half as much non-preferred rat chow.

Present data show that (R)-phenylpiracetam increases motivation, i.e., the work load, which animals are willing to perform to obtain more rewarding food. At the same time consumption of freely available normal food does not increase. Generally this indicates that (R)-phenylpiracetam increase motivation [...] The effect of (R)-phenylpiracetam is much stronger than that of methylphenidate and amphetamine.[11]

Pharmacology

Phenylpiracetam binds to α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mouse brain cortex with IC50 = 5.86 μM.[8]

Experiments performed on Sprague-Dawley rats in a European patent for using Phenylpiracetam to treat sleep disorders showed an increase in extracellular dopamine levels after administration. The patent asserts discovery of phenylpiracetam's action as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor[11] as its basis.

The peculiarity of this invention compared to former treatment approaches for treating sleep disorders is the so far unknown therapeutic efficacy of (R)-phenylpiracetam, which is presumably based at least in part on the newly identified activity of (R)-phenylpiracetam as the dopamine re-uptake inhibitor

Both enantiomers of phenylpiracetam have been described in peer-reviewed research as dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibitors in rodents, confirming the patent claim.[12][13] Their action at the noradrenaline transporter vary: the R enantiomer acts as a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (thus, an NDRI) with 11-fold lower affinity to NET than to DAT, while the S enantiomer has no such effect.[13]

History

Pilot-cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov described being issued and using Phenylpiracetam, as well as it being included in the Soyuz spacecraft's standard emergency medical kit, during his 197-days working in space aboard the Mir space station. He reported "the drug acts as the equalizer of the whole organism, "tidying it up", completely excluding impulsiveness and irritability inevitable in the stressful conditions of space flight."[2]

Availability

While not prescribed as a pharmaceutical in the West, in Russia it was available as a prescription medicine under the name Phenotropil. It was discontinued in April 2017 due to licensing issues.[14]

Phenylpiracetam is not scheduled by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.[15]

Athlete doping

Phenylpiracetam has been shown to possess a stimulant action in animal models and thus appears on the list of stimulants banned for in-competition use by the World Anti-Doping Agency. This list is applicable in all Olympic sports.[16][11]

See also

- Doping in sport

- Methylphenylpiracetam, a methylated analog

- Phenylpiracetam hydrazide

- Phensuximide, a succinimide analog

- Racetams

- Phenibut, also included in cosmonaut medical kits

References

- ↑ "WHO Drug Information, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2010" (PDF). p. 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Фенотропил: закономерное лидерство" [Phenotropil: natural leadership]. Medi.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Malykh AG, Sadaie MR (February 2010). "Piracetam and piracetam-like drugs: from basic science to novel clinical applications to CNS disorders". Drugs. 70 (3): 287–312. doi:10.2165/11319230-000000000-00000. PMID 20166767. S2CID 12176745.

- ↑ Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Grinberga S, Vorona M, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (November 2011). "Investigation into stereoselective pharmacological activity of phenotropil". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 109 (5): 407–412. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00742.x. PMID 21689376.

- ↑ Kim S, Park JH, Myung SW, Lho DS (November 1999). "Determination of carphedon in human urine by solid-phase microextraction using capillary gas chromatography with nitrogen-phosphorus detection". The Analyst. 124 (11): 1559–1562. Bibcode:1999Ana...124.1559K. doi:10.1039/a906027h. PMID 10746314.

- ↑ Savchenko AI, Zakharova NS, Stepanov IN (2005). "[The phenotropil treatment of the consequences of brain organic lesions]". Zhurnal Nevrologii I Psikhiatrii Imeni S.S. Korsakova. 105 (12): 22–26. PMID 16447562.

- ↑ WO application 2014005721, Russ H, Dekundy A, Danysz W, "Use of (r)-phenylpiracetam for the treatment of parkinson's disease", published 2014-01-09, assigned to Merz Pharma GmbH & Co. KGaA

- 1 2 Firstova YY, Abaimov DA, Kapitsa IG, Voronina TA, Kovalev GI (2011). "The effects of scopolamine and the nootropic drug phenotropil on rat brain neurotransmitter receptors during testing of the conditioned passive avoidance task". Neurochemical Journal. 28 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1134/S1819712411020048. S2CID 5845024.

- ↑ Bobkov I, Morozov IS, Glozman OM, Nerobkova LN, Zhmurenko LA (April 1983). "[Pharmacological characteristics of a new phenyl analog of piracetam--4-phenylpiracetam]". Biulleten' Eksperimental'noi Biologii I Meditsiny. 95 (4): 50–53. PMID 6403074.

- ↑ Tiurenkov IN, Bagmetov MN, Epishina VV (2007). "[Comparative evaluation of the neuroprotective activity of phenotropil and piracetam in laboratory animals with experimental cerebral ischemia]". Eksperimental'naia i Klinicheskaia Farmakologiia. 70 (2): 24–29. PMID 17523446.

- 1 2 3 EP application 20140000021, "Use of (r)-phenylpiracetam for the treatment of sleep disorders", published 2015-07-08, assigned to Merz Pharma GmbH and Co KGaA

- ↑ Zvejniece L, Zvejniece B, Videja M, Stelfa G, Vavers E, Grinberga S, et al. (October 2020). "Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activity of DAT inhibitor R-phenylpiracetam in experimental models of inflammation in male mice". Inflammopharmacology. 28 (5): 1283–1292. doi:10.1007/s10787-020-00705-7. PMID 32279140. S2CID 215731963.

- 1 2 Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Vavers E, Makrecka-Kuka M, Makarova E, Liepins V, et al. (September 2017). "S-phenylpiracetam, a selective DAT inhibitor, reduces body weight gain without influencing locomotor activity". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 160: 21–29. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2017.07.009. PMID 28743458. S2CID 13658335.

- ↑ "В России прекращено производство популярного ноотропного препарата" [The production of a popular nootropic drug has been discontinued in Russia]. NEWS.MEDICINE (in Russian). 2018-01-03. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018.

- ↑ "List of Controlled Substances" (PDF). Division Control Division. Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). January 2017. p. 6.