| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

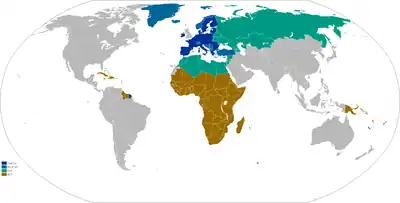

Although there has been a large degree of integration between European Union member states, foreign relations is still a largely intergovernmental matter, with the 27 states controlling their own relations to a large degree. However, with the Union holding more weight as a single entity, there are at times attempts to speak with one voice, notably on trade and energy matters. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy personifies this role.

Policy and actors

The EU's foreign relations are dealt with either through the Common Foreign and Security Policy decided by the European Council, or the economic trade negotiations handled by the European Commission. The leading EU diplomat in both areas is the High Representative Josep Borrell. The council can issue negotiating directives (not to be confused with directives, which are legal acts[1]) to the Commission giving parameters for trade negotiations.[2]

A limited amount of defence co-operation takes place within the Common Security and Defence Policy, as well as in programmes coordinated by the European Defence Agency and the Commission through the Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space . A particular element of this in the Union's foreign relations is the use of the European Peace Facility, which can finance the common costs CSDP missions in third states or assistance measures for third states.[3]

Diplomatic representation

History

The High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the EU's predecessor, opened its first mission in London in 1955, three years after non-EU countries began to accredit their missions in Brussels to the Community. The US had been a fervent supporter of the ECSC's efforts from the beginning, and Secretary of State Dean Acheson sent Jean Monnet a dispatch in the name of President Truman confirming full US diplomatic recognition of the ECSC. A US ambassador to the ECSC was accredited soon thereafter, and he headed the second overseas mission to establish diplomatic relations with the Community institutions.[4]

The number of delegates began to rise in the 1960s following the merging of the executive institutions of the three European Communities into a single Commission. Until recently some states had reservations accepting that EU delegations held the full status of a diplomatic mission. Article 20 of the Maastricht Treaty requires the Delegations and the Member States' diplomatic missions to "co-operate in ensuring that the common positions and joint actions adopted by the Council are complied with and implemented".[4]

As part of the process of establishment of the European External Action Service envisioned in the Lisbon Treaty, on 1 January 2010 all former European Commission delegations were renamed European Union delegations and by the end of the month 54 of the missions were transformed into embassy-type missions that employ greater powers than the regular delegations. These upgraded delegations have taken on the role previously carried out by the national embassies of the member state holding the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union and merged with the independent Council delegations around the world. Through this the EU delegations take on the role of co-ordinating national embassies and speaking for the EU as a whole, not just the commission.[5]

The first delegation to be upgraded was the one in Washington D.C., the new joint ambassador was João Vale de Almeida who outlined his new powers as speaking for both the Commission and Council presidents, and member states. He would be in charge where there was a common position but otherwise, on bilateral matters, he would not take over from national ambassadors. [6][7]

Locations

The EU sends its delegates generally only to the capitals of states outside the European Union and cities hosting multilateral bodies. The EU missions work separately from the work of the missions of its member states, however in some circumstances it may share resources and facilities. In Abuja it shares its premises with a number of member states.[8] Additionally to the third-state delegations and offices the European Commission maintains representation in each of the member states.[9]

Prior to the establishment of the European External Action Service by the Treaty of Lisbon there were separate delegations of the Council of the European Union to the United Nations in New York, to the African Union and to Afghanistan – in addition to the European Commission delegations there. In the course of 2010 these would be transformed into integrated European Union delegations.[10]

Member state missions

The EU member states have their own diplomatic missions, in addition to the common EU delegations. On the other hand, additionally to the third-state delegations and offices the European Commission maintains representation in each of the member states.[9] Where the EU delegations have not taken on their full Lisbon Treaty responsibilities, the national embassy of the country holding the rotating EU presidency has the role of representing the CFSP while the EU (formerly the commission) delegation speaks only for the commission.

Member state missions have certain responsibilities to national of fellow states. Consulates are obliged to support EU citizens of other states abroad if they do not have a consulate of their own state in the country. Also, if another EU state makes a request to help their citizens in an emergency then they are obliged to assist. An example would be evacuations where EU states help assist each other's citizens.[11]

No EU member state has embassy in the countries of Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados (EU delegation), Belize (EU office), Bhutan (Denmark Liaison office), Dominica, Gambia (EU office), Grenada, Guyana (EU delegation), Kiribati, Liberia (EU delegation), Liechtenstein, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa (EU office), Somalia, Solomon Islands, Swaziland (EU office), Tonga, Tuvalu, the sovereign entity Sovereign Military Order of Malta and the partially recognised countries Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic and Republic of China (Taiwan) (17 non-diplomatic offices). The European Commission also has no delegations or offices to most of them (exceptions mentioned in brackets).

The following countries host only a single Embassy of EU member state: Central African Republic (France, EU delegation), Comoros (France), Lesotho (Ireland, EU delegation), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Timor-Leste (Portugal, EU delegation), Vanuatu (France, EU delegation). The European Commission also has no delegations or offices to most of them (exceptions mentioned in brackets).

Relations

Africa and the Middle East

| Country | Formal relations began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 |

Algeria was part of many different empires and dynasties in its history before it became independent in 1962. The EU-Algeria Association Agreement of 2002, which came into force in 2005, laid the foundations for cooperation in several areas.[12] Among other things, tariffs were almost completely abolished by the end of 2020.[12] In 2017, new common objectives of the EU and Algeria were defined and adopted. Algeria is part of the Union for the Mediterranean which laid the foundation for a freetrade area for goods between the EU and all of the member countries.[13] The EU was Algeria's most important trading partner in 2019, accounting for nearly half of the country's international trade. Furthermore, the EU supports Algeria in joining the WTO since 2014.[12][14] | |

| 1988 |

In 2021 Bahrain signed, as most of the other gulf states, a Cooperation Agreement that aims to intensify cooperation with the EU on a political and economic level. Moreover, with its fellow GCC members it takes part in projects promoting diplomatic cooperation, renewable energies, economic diversification and cultural exchange.[15] In January 2021, a joint letter concerning the deterioration of the human rights situation in Bahrain was written to the European Union. The letter was undersigned by the human rights and advocacy groups from around the world, including ADHRB, Amnesty International, Freedom House, CIVICUS, PEN International, etc.[16] The EU members were demanded to address the deteriorating condition of human rights in Bahrain with the Bahraini delegation expected to visit Brussels on February 10, 2021 for an EU-Bahrain interactive human rights dialogue.[16] The letter called out the arbitrary detention of journalists for their critical work in Bahrain, unfair prosecution of defense lawyers, human rights defenders, and opposition leaders, death penalty, and mistreatment of prisoners. The European External Action Services (EEAS) acknowledged the letter on 25 January 2021.[16] | |

(Organisation) |

1988 |

The foundation of the relationship between the European Union and the Gulf region was laid in 1988, when the Gulf Cooperation Council (including Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates) signed the Cooperation Agreement with the EU. The objective of this treaty is the intensification of relations, mainly in political and economic sectors and research.[17][18][19] Today, exchange between the EU and the GCC takes place on many different levels; diplomatically, economically and culturally. The economic relations between the EU and the GCC are of crucial importance for both sides, illustrated by the fact that the EU is the second largest trading partner of the Gulf region, after China.[20][21] In 2018 the "EU-GCC Dialogue on Economic Diversification" project was established, which is supposed to strengthen economic exchange with a focus on the diversification of the gulf’s economy.[22] The European Green Deal, which could be seen as a threat to the Gulf state’s fossil fuel depended economy, has lately also been perceived as an opportunity to prepare for the post-oil era.[23] For this purpose, the UG-GCC clean energy network was founded in 2010, which is a partnership focused on increasing renewable and clean energy in both regions.[24] In 2020 the political and diplomatic partnership was renewed and intensified through the "Enhanced EU-GCC Political Dialogue, Cooperation and Outreach" treaty. On a cultural level, projects such as Erasmus+ promote cultural exchange between the regions and enable students and young people to study and research abroad.[25] |

| 2018 | ||

| 1966 |

In 2004 the Association Agreement came into effect, which laid the foundation for future cooperation between the EU and Egypt. Moreover, a free trade area was established, which the EU aims to intensify further.[26] In 2020 trade between Egypt and the EU was worth 24.5 million EUR, which makes the EU Egypt's main trading partner. Furthermore, both cooperate within the Union for the Mediterranean.[27] In 2017 the terms of the partnership were revised, due to the new European Neighborhood policy. Egypt and the EU agreed on distinct guidelines that should shape the relationship until 2020. Therein, they focused on the Egyptian "Sustainable Development Strategy – Vision 2030" and emphasized their shared values of human rights and democracy.[26] At large, the partnership focuses on the promotion of societal prosperity and justice, for example in terms of education and healthcare, as well as in regard to the protection of minority groups. Another core theme is the funding of economic development, for instance in the form of investment into renewable energies with the goal to enhance sustainability.[26] When it comes to foreign policy, the EU and Egypt seek to follow a joint agenda, which aims at stabilizing the Mediterranean region, as well as the Middle East and Africa. This includes tackling economic and political issues, such as combating radicalisation and terrorism. Furthermore, the EU intends to intensify its cooperation with the League of Arab States (LAS), which is hosted by Egypt.[26][28] | |

| Prior to 2003 the EU and Iraq had barely any political connection or cooperation, since the relation was mostly characterised by distrust. The overthrow of the Saddam Hussein regime in March 2003 however changed this; the EU now plays an increasingly active role in the Middle Eastern country.[29] In the time period between 2003 and 2018 the EU spent around 3 billion euros on financial support for Iraq. For instance, they established projects concerned with improving the trade relations and cultural ties between the EU and Iraq.[29] Furthermore, the EU is involved with providing humanitarian aid, improving the human rights situation in Iraq and supports the further development of sustainable energies and the educational system.[29]

On the other hand, the start of the Iraq war in 2003 also revealed large disunity between the EU member states concerning the United States’ military intervention in Iraq. This made a coherent and mutual foreign policy towards the situation in Iraq difficult.[29] | ||

|

Due to Iran's nuclear programme there are several sanctions in place against the country, which regulate and complicate trade. Prior to the implementation of these sanctions, the EU was the most important trading partner of Iran, although the two parties have no trade agreement. In connection with JCPOA, which was signed in 2015 and to which the EU belongs, some sanctions were eased in contrast there were stricter conditions for Iran's nuclear program. With the withdrawal of the U.S. in 2019, sanctions came into force again but some EU states partially bypassed them through the specially established INSTEX.[30] Also, the EU supports Iran in the attempt to become a WTO member.[31][32][33] | ||

| 1995 |

In 1995 Israel became a member of the EUs Southern Neighborhood. Trade between the EU and Israel is conducted on the basis of the Association Agreement, which came into effect in 2000.[34] The European Union is Israel's major trading partner.[35] In 2004 the total volume of bilateral trade (excluding diamonds) came to over €15 billion. 33% of Israel's exports went to the EU and almost 40% of its imports came from the EU. Under the Euro-Mediterranean Agreement from 2000, the EU and Israel agreed on free trade regarding industrial products.[36] The two sides have granted each other significant trade concessions for certain agricultural products, in the form of tariff reduction or elimination, either within quotas or for unlimited quantities. However, goods from Israeli settlements in the Israeli-occupied territories are not subjected to the free trade agreement, as they are not considered Israeli. In 2009, a German court solicited the European Court of Justice for a binding ruling on whether goods manufactured in Israeli settlements in the Israeli-occupied territories should fall under duty exemptions in the Association Agreement. The German government stated as its position that there can be no exemption from customs duty for "goods from the occupied territories".[37] The court, agreeing with the German government, ruled in February 2010 that settlement goods were not entitled to preferential treatment under the customs rules of the EU-Israel Association Agreement, and allowed the EU to impose import duties on settlement products.[38] In December 2009, the Council of the European Union endorsed a set of conclusions on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict which forms the basis of present EU policy.[39] It reasserted the objective of a two-state solution, and stressed that the union "will not recognise any changes to the pre-1967 borders including with regard to Jerusalem, other than those agreed by the parties." It recalled that the EU "has never recognised the annexation of East Jerusalem" and that the State of Palestine must have its capital in Jerusalem.[40] A year later, in December 2010, the Council reiterated these conclusions and announced its readiness, when appropriate, to recognise a Palestinian state, but encouraged a return to negotiations.[41] Eight of its then 27 member states had recognised the State of Palestine. In 2020 Israel was the EU’s 24th biggest trading partner and the EU was the most important trading partner of Israel.[34] | |

| 1995 | Jordan has been a member of the EUs Southern Neighborhood Programme since 1995 and in this context received 765 million euros in the period between 2014–2016.[42] A free trade agreement between Jordan and the EU entered into force in 2002.[42] The EU was Jordan's most important trading partner in 2020 and also the largest foreign investor.[42] | |

| 1988 |

Exchange and cooperation between Kuwait and the EU have intensified since July 2016, after the completion of the EEAS agreement (Cooperation Agreement with the European External Action Service). In terms of economic connections, the EU is of major importance to Kuwait and constitutes Kuwait’s third biggest trading partner.[43] | |

| In 2002, an agreement was concluded between the EU and Lebanon which guarantees free trade for certain goods.[44] The EU was Lebanon's most important trading partner in 2020.[44] Since 1999, Lebanon has been trying to join the WTO, which the EU supports.[44] Lebanon is a member of the Southern Neighborhood and the Union for the Mediterranean.[44] Moreover, the EU also supports democracy and security in Lebanon among other issues.[45] | ||

|

Libya is a member of the Southern Neighborhood, but has, unlike the other member states, no free trade agreement with the EU.[46] Libya is also not a member of the Union for the Mediterranean, but functions as an observer since 1999.[47] Prior to the 2011 Libyan civil war, the EU and Libya were negotiating a cooperation agreement which has now been frozen.[48] The EU worked to apply sanctions over the Libyan conflict, provide aid and some members participated in military action.[49] Since 2016, the EU has been working closely with the Libyan Coast Guard to regulate flight routes across the Mediterranean towards the EUs external border. Human rights organizations accuse the parties involved in this cooperation of serious crimes, including crimes against humanity.[50][51] Since 2016 the EU Global Strategy puts a special focus on the North African countries, of which Libya is often seen playing an important role for prosperity and security in the Mediterranean region.[52][53] In 2020 the EU was Libya's most important trade partner.[46] | ||

| 1960 | A free trade area between the EU and Morocco was concluded in 1996 and extended in 2019. The trade relations between Morocco and the EU are very close, in 2020 Morocco constituted the 20th most important trading partner of the EU.[54] The EU on the other hand is Morocco's most important trading partner, with over half of its imports and exports going to and coming from EU states. Furthermore, the EU was the biggest foreign investor in the country in 2020.[54] Marocco is the largest partner of all Southern Neighborhood member states, of which it has been a member since 1995.[54] | |

| 2018 | ||

| 1988 |

The relationship between the EU and Oman focuses on the energy sector and maritime security, for example in combating piracy in Africa.[55] In 2018 the Cooperation Agreement was signed, which is supposed to strengthen economic exchange, with an emphasis on controlling illegal fishing, and promoting clean energy and non-oil exports.[55][56] | |

| 1975 |

Relations between the European Union and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) were established in 1975 as part of the Euro-Arab Dialogue.[57] The EU is a member of the Quartet and is the single largest donor of foreign aid to Palestinians.[58][59] Palestine has been a member of the EU Southern Neighborhood since 1995. The EU maintains a representative office in Ramallah, accredited to the PNA.[60] The PLO's general delegation in Brussels, accredited to the EU,[61] was first established as an information and liaison bureau in September 1976.[62] Other representations are maintained in almost every European capital, many of which have been accorded full diplomatic status.[57] In western Europe, Spain was the first country granting diplomatic status to a PLO representative, followed later by Portugal, Austria, France, Italy and Greece.[63] The EU has insisted that it will not recognise any changes to the 1967 borders other than those agreed between the parties. Israel's settlement program has therefore led to some tensions, and EU states consider these settlements illegal under international law.[64][65] In July 2009, EU foreign policy chief Javier Solana called for the United Nations to recognise the Palestinian state by a set deadline even if a settlement had not been reached: "The mediator has to set the timetable. If the parties are not able to stick to it, then a solution backed by the international community should ... be put on the table. After a fixed deadline, a UN Security Council resolution ... would accept the Palestinian state as a full member of the UN, and set a calendar for implementation."[66] In 2011, the Palestinian government called on the EU to recognise the State of Palestine in a United Nations resolution scheduled for 20 September. EU member states grew divided over the issue. Some, including Spain, France and the United Kingdom, stating that they might recognise if talks did not progress, while others, including Germany and Italy, refused. Catherine Ashton said that the EU position would depend on the wording of the proposal.[67] At the end of August, Israel's defence minister Ehud Barak told Ashton that Israel was seeking to influence the wording: "It is very important that all the players come up with a text that will emphasise the quick return to negotiations, without an effort to impose pre-conditions on the sides."[68] Trade is very much affected and restricted by the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine.[69] | |

| 1988 | Generally speaking, the main sectors of cooperation between the EU and Qatar are military defense, economic exchange and energy.[18] In 2018 the 1988 agreement was renewed by Qatar and the EU through the completion of a new EEAS Cooperation Agreement which aims at intensifying political exchange and puts a focus on development and innovation.[18][70] In terms of politics and crisis handling the European Union has failed to take over a position of leverage and mediation in regional conflicts in the Gulf region and therefore the region, and especially Qatar, instead continues to focus on the US as their main partner in political and economic terms.[71] | |

| 1988 |

The first embassy of the European Union was established in Riyadh in 2004. In October 2021 a Cooperation Agreement was signed, which emphasizes the regions’ cooperation in political and technical sectors and schedules a yearly exchange meeting between senior officials.[72] The EUNIC cluster (European Union National Institutes for Culture) has been active since 2021 and supports cultural exchange. In terms of economic cooperation, the EU is of major importance, since it is, after China, Saudi Arabia’s 2nd biggest trading partner and imports Saudi Arabian oil and chemicals.[72][55] Geopolitically, Saudi Arabia does not consider the European Union to be a main player and orients itself more towards the US. An exemption of this are France and the United Kingdom, who are, for historic reasons and due to their seats in the UN Security Council, of particular importance for Saudi Arabia. Moreover, Germany is increasingly mentioned as an important partner as well.[73] Criticism about human rights violations in the country, voiced by EU member states, have complicated the diplomatic relationship, even though the criticism itself had little influence on Saudi Arabian politics.[74] | |

|

South Africa has strong cultural and historical links to the European Union (EU) (particularly through immigration from the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (a former member), Germany, France, and Greece) and the EU is South Africa's biggest investor.[75] Since the end of South Africa's apartheid, EU South African relations have flourished and they began a "Strategic Partnership" in 2007. In 1999 the two sides signed a Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) which entered into force in 2004, with some provisions being applied from 2000. The TDCA covered a wide range of issues from political cooperation, development and the establishment of a free trade area (FTA).[75] South Africa is the EU's largest trading partner in Southern Africa and has a FTA with the EU. South Africa's main exports to the EU are fuels and mining products (27%), machinery and transport equipment (18%) and other semi-manufactured goods (16%). However they are growing and becoming more diverse. European exports to South Africa are primarily machinery & transport equipment (50%), chemicals (15%) and other semi-machinery (10%).[76] | ||

| 2012 |

The EU is one of South Sudan's main partners in sectors such as trade, political relationships, peacekeeping and humanitarian aid.[77][78] It supported the country after its declaration of independence in 2011.[78] Following the outbreak of the civil war in 2013, the EU abandoned their civil mission EUAVSEC (European Union Aviation Security CSDP Mission in South Sudan) and since has not renewed it.[79] Nevertheless, the EU has supported South Sudan in many different areas since the beginning of the crisis. For instance, the EU Parliament has condemned human rights violations in the country in the context of the civil war.[79] Furthermore, the EU supports the IGAD and has provided 1 billion Euro of humanitarian aid since 2011. It supported the peace process in the country in the form of the development of the RARCSS (Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan).[78] In 2014 the EU also implemented an arms embargo targeting both Sudan and South Sudan.[79] Following the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, the EU aided the country through financial and material support.[78] | |

| 1975 | The focus of the EU's work in Sudan lies on peacekeeping, humanitarian, health and educational projects with an emphasis on supporting Sudan's democratic tranisition.[80] The EU and Sudan take part in ongoing negotiations concerning an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).[81] The Multiannual Indicative Programme (MIP) predefines humanitarian and peacekeeping work in the country between 2021 and 2027.[81] In 2022 alone, the EU supported Sudan with 40 million Euro of humanitarian aid, for instance in the form of financial assistance during the COVID-19 crisis.[82] In 2021 the EU officially condemned the military coup d'etat in Sudan and announced serious consequences targeting its financial aid.[83] Following riots in 2022, the EU, again, convicted ongoing human rights violations in the country, especially violent attacks by the military against protesters.[84] | |

| 1977 | In 1977 the foundations for relations between the EU and Syria were laid through the implementation of the Cooperation Agreement which targeted cooperation in financial and economic sectors and development. The EU-Syria Association Agreement from 1978 was supposed to further intensify exchange between the countries, but was never officially approved by the Syrian regime. In 2007 the Country Strategy Paper (CSP) was implemented, which shaped the relationship between the EU and Syria up until 2013 and focused on political, economic and social reforms. Despite the non-democratic character of the Syrian government, the EU upheld its trade relations with the state without addressing continuing human rights violations.[85]

Even though EU member states kept tolerating the Assad regime during the uprisings in March 2011, they later demanded Bashar al-Assad to step down and enable the democratisation of Syria. Following the escalation of the protests into a civil war, the EU imposed economic and military sanctions and ended its diplomatic relationships with Syria with the goal of changing the regime. The Syrian government managed to circumvent most of these sanctions by diversifying its trade relationships and importing arms from other non-EU states. In 2013 a disagreement between EU member states about whether Syrian rebel groups should be supported, resulted in relieving oppositional groups from the arm embargo.[85] The western approach towards to Syrian crisis changed in 2014 when the terror organisation ISIS gained power. The EU shifted its focus from the Assad regime towards the fight against the Islamic State due to increasing security concerns. Actions implemented by the EU included humanitarian aid and support for the rebel groups. Even though the EU states never actively took part in military actions in Syria, they supported already existing oppositional groups in Syria and the US-led coalition through financial and material assistance.[85] The US’ military cooperation with the PYD/YPG brought the EU into a difficult situation. Since Turkey recognises the PYD as a terror group, EU states were worried it could threaten their relationship to Turkey.[85] The influx of multiple million Syrian refugees into the EU, especially in 2015, led to disunion between European states concerning the allocation of the migrants.[85] In March 2021 the EU, in cooperation with the UN, approved a new aid package of 5.3 EUR billion targeted at improving the humanitarian situation in Syria and its neighbour countries. Sanctions on the Syrian government and Syrian individuals will stay in place until at least 1 June 2022.[86] | |

| 1998 |

Tunisia was the first Mediterranean country to sign an association agreement with the EU and fully implement it, enabling a free trade area, in 1998.[87] It participates in the Union for the Mediterranean and has signed a dispute mechanism agreement with the EU.[87] While the EU is of major importance for the Tunisian economy, constituting its largest trading partner in 2020, Tunisia only accounted for 0,5% of European foreign trade.[87] Furthermore, Tunisia and the EU are in constant negotiations to deepen the cooperation and relations between the countries.[87][88] | |

| 2018 | ||

| 1988 | Issues such as anti-terrorism and maritime security have become an increasingly important part of the partnership between the EU and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).[89] The country hosts secretariats of different EU projects, such as the CBRN center. In economic terms, trade between the regions adds up to 55 billion USD, which makes the EU UAE’s largest trading partner.[89] Even though the UAE uphold important diplomatic relations, specifically to France, the United Kingdom and Germany, the EU itself is often perceived as disunited, indecisive and slow-reacting. Especially the European Union’s inaction on security issues in the Middle Eastern region is often criticized by the UAE.[90] Nevertheless, Europe continues to influence the region on a cultural and educational level.[90]

In 2021 the European parliament passed a resolution condemning human rights violations by the government of the UAE and demanded the release of multiple human rights activists who had been imprisoned.[91] The Arab league subsequently questioned the EU's right to judge the political situation in Middle Eastern countries.[92] | |

|

In 2017, Federica Mogherini, the foreign minister of the European Union stirred controversy and diplomatic confusion over her statement that the trade agreements between Morocco and the EU would not be affected by the 2016 ruling by the European Court of Justice on the scope of trade with Morocco. This ruling confirmed that bilateral trade deals, such as the EU–Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement, covers only agricultural produce and fishing products originating within the internationally recognized borders of Morocco, thus explicitly excluding any product sourced from Western Sahara or its territorial waters. The international community, including the EU, unanimously rejects Morocco's territorial claim to Western Sahara.[93][94][95][96] | ||

| 1997 | The EU is currently active in Yemen in the fields of conflict resolution, development aid and humanitarian aid concerning the Yemeni Civil War, and is one of the most important donor countries in favour of Yemen.[97][98] However, there are also accusations that EU states such as Germany or France export weapons to countries that are allied with Yemen and that these weapons are also used in the Yemeni conflict.[99] | |

The Americas

| Country | Formal relations began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

The European Union relations and cooperation with Barbados are carried out both on a bilateral and a Caribbean-regional basis. Barbados is party to the Cotonou Agreement, through which As of December 2007 it is linked by an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Commission. The pact involves the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) subgroup of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP). CARIFORUM is the only part of the wider ACP-bloc that has concluded the full regional trade-pact with the European Union. There are also ongoing EU-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and EU-CARIFORUM dialogues.[100] The Mission of Barbados to the European Union is located in Brussels, while the Delegation of the European Union to Barbados and its regional neighbors is in Bridgetown. | ||

|

Canada's relationship with Europe is an outgrowth of the historic connections spawned by colonialism and mass European immigration to Canada. Canada was first settled by the French, and after 1763 was formally added to the British Empire after its capture in the Seven Years' War. The links may diminish after the United Kingdom left the EU in 2020: the UK has extremely close relations with Canada, due to its British colonial past and both being realms of the Commonwealth. Historically, Canada's relations with the UK and USA were usually given priority over relations with continental Europe. Nevertheless, Canada had existing ties with European countries through the Western alliance during the Second World War, the United Nations, and NATO before the creation of the European Economic Community. The history of Canada's relations with the EU is best documented in a series of economic agreements: In 1976 the European Economic Community (EEC) and Canada signed a Framework Agreement on Economic Co-operation, the first formal agreement of its kind between the EEC and an industrialized third country. Also in 1976 the Delegation of the European Commission to Canada opened in Ottawa. In 1990 European and Canadian leaders adopted a Declaration on Transatlantic Relations, extending the scope of their contacts and establishing regular meetings at Summit and Ministerial level. In 1996, a new Political Declaration on EU-Canada Relations was made at the Ottawa Summit, adopting a joint Action Plan identifying additional specific areas for co-operation. | ||

| Caribbean (region) | The independent countries of the Caribbean region (Namely the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) + Dominican Republic are known by the European Union as CARIFORUM (under the Lomé Convention and Cotonou Agreement). CARIFORUM makes up one of three parts of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States. CARIFORUM remains the only region of the A.C.P. to have concluded with the E.U. an Economic Partnership Agreement. Under the EPA, the E.U. maintains an active joint ACP–EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly. | |

| Latin America (region) | The Union has been developing ties with other regional bodies such as the Andean Community and Mercosur, with plans for association agreements between the EU and the two other blocs underway to help trade, research, democracy and human rights.[101][102] Chile and Mexico have an Association Agreement with the EU.

A 2.6-billion euro financial package for Latin America was also put forward[101] with 840-million euro for Central America.[103] A major forum for European relations with Latin America is the Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union Summit, a biannual meeting of heads of state and government held since 1999. | |

| Greenland is an autonomous territory of an EU member state, but lies outside of the EU, and hence although it is not part of the EU, it has strong ties to it. | ||

| 2018 | ||

| 2018 | ||

|

The European Union and the United States have held diplomatic relations since 1953.[104] The two Unions play leading roles in international political relations, and what one says matters a great deal not only to the other, but to much of the rest of the world.[105] And yet they have regularly disagreed with each other on a wide range of specific issues, as well as having often quite different political, economic, and social agendas. Understanding the relationship today means reviewing developments that predate the creation of the European Economic Community (precursor to today's European Union) Euro-American relations are primarily concerned with trade policy. The EU is a near-fully unified trade bloc and this, together with competition policy, are the primary matters of substance currently between the EU and the USA. Both are dependent upon the other's economic market and disputes affect only 2% of trade. See below for details of trade flows.[5] | ||

| 2018 | ||

Asia-Pacific

| Country | Formal relations began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| There are annual meetings between the EU and the ASEAN Plus Three. EU-ASEAN relations cover a broad range of topics, including peace and security; economic cooperation and trade; connectivity and the digital transition; sustainable development, climate change and energy; disaster preparedness; decent work; and health. At the 2022 EU-ASEAN Commemorative Summit, the EU and ASEAN signed a 2023–2027 Plan of Action, outlining the details of how this cooperation would be operationalised. Relations have sometimes been strained due to the membership of Myanmar in ASEAN.[106] Notably, in 2006 the European Union threatened to boycott an EU-ASEAN meeting when Myanmar was due to take over the presidency of ASEAN in 2006, however Myanmar eventually gave up the presidency.[107] However, in recent years this has been solved by having Myanmar participate in summits only at a technical level.[106] | ||

|

Australia and the European Union (EU) have strong historical and cultural ties. The two have solid relations and often see eye-to-eye on international issues. The EU-Australian relations are founded on a Partnership Framework, first agreed in 2008. It covers not just economic relations, but broader political issues and cooperation.[108] The EU is Australia's second largest trading partner, after China, and Australia is the EU's 17th. Australia's exports is dominated by mineral and agricultural goods. However 37% of trade is in commercial services, especially transportation and travel. EU corporations have a strong presence in Australia (approximately 2360) with an estimated turnover of €200 bn (just over 14% of total sales in Australia). These companies directly created 500,000 jobs in Australia. The EU is Australia's second largest destination of overseas investment and the EU is by far Australia's largest source of foreign investment €2.8 billion in 2009 (€11.6 billion in 2008). Trade was growing but ebbed in 2009 due to the global financial crisis.[109] A Free Trade Agreement between Australia and the EU is currently under negotiation, with conclusion expected in 2023.[110] | ||

| The EU is China's largest trading partner, and China is the EU's second largest trading partner. Most of this trade is in industrial and manufactured goods. Between 2009 and 2010 alone EU exports to China increased by 38% and China's exports to the EU increased by 31%.[111][112] However, there are sources of tension, such as human rights and the EU's arms embargo on China. Both the United States and the European Union as of 2005 have an arms embargo against the PRC, put in place in 1989 after the events of Tiananmen Square. The US and some EU members continue to support the ban but others, spearheaded by France, have been attempting to persuade the EU to lift the ban, arguing that more effective measures can be imposed, but also to improve trade relations between the PRC and certain EU states. The US strongly opposes this, and after the PRC passed an anti-secession law against Taiwan the likelihood of the ban being lifted diminished somewhat.

There have been some disputes, such as the dispute over textile imports into the EU (see below). China and the EU are increasingly seeking cooperation, for example China joined the Galileo project investing €230 million and has been buying Airbus planes in return for a construction plant to be built in China; in 2006 China placed an order for 150 planes during a visit by the French President.[113] Also, despite the arms embargo, a leaked US diplomatic cable suggested that in 2003 the EU sold China €400 million of "defence exports" and later, other military grade submarine and radar technology. Interest in closer relations started to rise as economic contacts increased and interest in a multipolar system grew. Although initially imposing an arms embargo on China after Tiananmen (see arms embargo section below), European leaders eased off China's isolation. China's growing economy became the focus for many European visitors and in turn Chinese businessmen began to make frequent trips to Europe. Europe's interest in China led to the EU becoming unusually active with China during the 1990s with high-level exchanges. EU-Chinese trade increased faster than the Chinese economy itself, tripling in ten years from US$14.3 billion in 1985 to US$45.6 billion in 1994.[114] However political and security co-operation was hampered with China seeing little chance of headway there. Europe was leading the desire for NATO expansion and intervention in Kosovo, which China opposed as it saw them as extending US influence. However, by 2001 China moderated its anti-US stance in the hopes that Europe would cancel its arms embargo but pressure from the US led to the embargo remaining in place. Due to this, China saw the EU as being too weak, divided and dependent on the US to be a significant power. Furthermore, it shared too many of the US' concerns about China's authoritarian system and threats of force over Taiwan. Even in the economic sphere, China was angered at protectionist measures against its exports to Europe and the EU's opposition to giving China the status of market economy in order to join the WTO.[114] However, economic cooperation continued, with the EU's "New Asia Strategy", the first Asia–Europe Meeting in 1996, the 1998 EU-China summit and frequent policy documents desiring closer partnerships with China. Although the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis dampened investors enthusiasm, China weathered the crisis well and continued to be a major focus of EU trade. Trade in 1993 saw a 63% increase from the previous year. China became Europe's fourth largest trading partner at this time. Even following the financial crisis in 1997, EU-Chinese trade increased by 15% in 1998.[114] | ||

| The EU and Hong Kong share values of democracy, human rights and market economics. Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office, Brussels is the official representation of Hong Kong to the European Union.[115] | ||

|

The EU and Japan share values of democracy, human rights and market economics. Both are global actors and cooperate in international fora. They also cooperate in each other's regions: Japan contributes to the reconstruction of the western Balkans and the EU supports international efforts to maintain peace in Korea and the rest of Asia.[116] The EU Japanese relationship is anchored on two documents: the Joint Declaration of 1991 and the Action Plan for EU-Japan Cooperation of 2001. There are also a range of fora between the two, including an annual summit of leaders and an inter-parliamentary body.[116] Both sides have now agreed to work towards a deep and comprehensive free trade agreement. Four agreements thus far have been signed by the two sides;[117]

Japan is the EU's 6th largest export market (3.2% in 2010 with a value of €44 billion). EU exports are primarily in machinery and transport equipment (31.3%), chemical products (14.1%) and agricultural products (11.0%). Despite a global growth in EU exports, since 2006 EU exports to Japan have been declining slightly. In 2009, due to the global financial crisis, exports saw a 14.7% drop; however in 2010 they recovered again by 21.3%. Japan is also the 6th largest source of imports to the EU (4.3% in 2010 with a value of €65 billion). Japanese exports to Europe are primarily machinery and transport equipment (66.7%). The EU is Japan's 3rd largest trading partner (11.1% of imports, 13.3% exports). Trade in commercial services were €17.2 billion from the EU to Japan and €12.7 billion from Japan to the EU.[117] The trade relationship between the two has been characterised by strong trade surpluses for Japan, though that has moderated in the 2000s. Doing business and investing in Japan can be difficult for European countries and there have been some trade disputes between the two parties. However the slowdown in the Japanese economy encouraged it to open up more to EU business and investment.[117] While working on reducing trade barriers, the main focus is on opening up investment flows.[116] | ||

|

The relations started with the 1980 European Commission–ASEAN Agreement and were developed since the formation of European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957.[118][119] In 2011, Malaysia is the European Union second largest trading partner in Southeast Asia after Singapore and the 23rd largest trading partner for the European Union in the world,[119][120] while the European Union is Malaysia's 4th largest trading partner.[121] | ||

|

New Zealand and the European Union (EU) have strong historical and cultural ties. The two have solid relations and often see eye-to-eye on international issues. The EU-New Zealand relations are founded on a Joint Declaration on Relations and Cooperation, first agreed in 2007. It covers not just economic relations, but broader political issues and cooperation.[122] The EU is New Zealand's second largest trading partner, after Australia, and New Zealand is the EU's 49th. New Zealand's exports is dominated by agricultural goods. The stock of EU foreign direct investment in New Zealand is €9.8bn and the stock of New Zealand's investment in the EU is €4.5bn.[123] A Free Trade Agreement between the EU and New Zealand is expected to be signed in early 2023.[124] | ||

| The EU accounts for 20% of Pakistani external trade with Pakistani exports to the EU amounting to €3.4 billion, mainly textiles and leather products) and EU exports to Pakistan amounting to €3.8 billion (mainly mechanical and electrical equipment, and chemical and pharmaceutical products.[125] | ||

| The European Union and the Philippines shares diplomatic, economic, cultural and political relations. The European Union has provided €3 million to the Philippines to fight poverty and €6 million for counter-terrorism against terrorist groups in the Southern Philippines. The European Union is also the third largest trading partner of the Philippines with the Philippines and The European Union importing and exporting products to each other. There are at least (estimated) 31,961 Europeans (not including Spaniards) living in the Philippines. | ||

| 2014 | ||

|

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the European Union (EU) are important trade partners: Korea is the EU's 9th largest trading partner and the EU is Korea's second largest export market. The two have signed a free trade agreement which will be provisionally applied by the end of 2011.[126] The first EU – South Korea agreement was Agreement on Co-operation and Mutual Administrative Assistance in Customs Matters (signed on 13 May 1997).[127] This agreement allows the sharing of competition policy between the two parties.[128] The second agreement, the Framework Agreement on Trade and Co-operation (enacted on 1 April 2001). The framework attempts to increase co-operation on several industries, including transport, energy, science and technology, industry, environment and culture.[128][129] In 2010, the EU and Korea signed a new framework agreement and a free trade agreement (FTA) which is the EU's first FTA with an Asian country and removes virtually all tariffs and many non-tariff barriers. On the basis of this, the EU and Korea decided in October 2010 to upgrade their relationship to a Strategic Partnership. These agreements will be provisionally in force by the end of 2011.[126] EU-Korea summits have taken place in 2002 (Copenhagen), 2004 (Hanoi) and 2006 (Helsinki) on the sidelines of ASEM meetings. In 2009, the first stand alone bilateral meeting was held in Seoul. The European Parliament delegation for relations with Korea visits the country twice a year for discussions with their Korean counterparts. Meetings at foreign minister level take place at least once a year on the sidelines of ASEAN regional form meetings, however meetings between the Korean foreign minister and the EU High Representative have occurred more frequently, for example at G20 meetings. At hoc meetings between officials occur nearly monthly.[130] Further Information: Foreign relations of South Korea#Europe.[131] | ||

| 2018 | ||

| Informal relations | ||

| 2018 | ||

| 1996 |

Europe and Central Asia

The EU does not officially recognize the Eurasian Economic Union due to its disagreements with Russia, the EAEU's largest member state.[132]

The EU regularly holds High-level Political and Security Dialogues (HLDs) with the countries of Central Asia which include Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, with Afghanistan often invited as a guest.[133] The HLDs with these states have a focus on security, and provide a formal platform to exchange views and ideas, advance collaboration and support EU involvement in the Central Asian region.[133]

An update to the 10-year-old EU-Central Asia strategy is expected to be developed by the end of 2019.[134] The new EU Central Asia Strategy was introduced at the EU-Central Asia Ministerial meeting in Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic, on 7 July 2019. Federica Mogherini also presented a set of EU funded regional programmes totaling €72 million. The new programmes cover the following sectors: sustainable energy, economic empowerment, education, and inclusive sustainable growth.[135]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU allocated more than €134 million to Central Asia as part of its "Team Europe" solidarity package. The funds were granted to strengthen the health, water and sanitation systems and address the socio-economic repercussions of the crisis.[136]

The first-ever "EU-Central Asia Economic Forum" is set to take place in 2021. The Forum will focus on innovative and sustainable approach to economic and business development, as well as green economy.[136]

The first Central Asia-EU high-level meeting took place in Astana on 27 October 2022.[137] The participants (representatives from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and the EU) issued a joint communique, embracing the steps towards the institutionalisation of the relationship between the Central Asian nations and the EU.[137]

EU Programmes in Central Asia

Border Management Programme in Central Asia

The EU launched in 2002 the BOMCA to mitigate the impacts of human trafficking, trafficking of drugs, organised crime and terrorism on EU interests and regional partners.[138]

Central Asia Drug Action Programme

The CADAP works to bolster drug policies of Central Asian states by providing assistance policy makers, industry experts, law enforcement, educators and medical staff, victims of drug abuse, the media and the general public.[139]

| Country | Formal relations began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Albania is an EU candidate since June 2014, and has applied for membership since 2009. Majority of Albanian policy especially foreign is in line with EU, relations have been very strong and warm. | ||

| Andorra co-operates with the EU, and uses the euro but is not seeking membership. | ||

| 1991 |

The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) (signed in 1996 and in force since 1999) served as the legal framework for EU-Armenia bilateral relations. Since 2004, Armenia and the other South Caucasus states have been part of the European Neighbourhood Policy, encouraging closer ties with the EU. Armenia and the EU were set to sign a free trade and Association Agreement in September 2013, however the agreement was called off by Armenia, prior to Armenia joining the Eurasian Union in 2014. Though, a revised Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) was later finalized between Armenia and the EU in November 2017.[140] Armenia also participates in the Eastern Partnership Program and the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly; which aims at forging closer political and economic integration with the EU. In April 2018, Armenia began implementing actions for launching visa liberalization dialogue for Armenian citizens travelling into the Schengen area.[141] The Delegation of the European Union to Armenia is located in Yerevan. | |

| 1991 | ||

| 1991 | Belarus has strained relations with the EU as it is the only dictatorship left on the EU's borders. | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina is a potential EU candidate that has completed an association agreement. It is one of the few countries in the western Balkans which has not yet made a formal application, however it is experiencing problems integrating its component states. It is still under partial control of the international community via the EU-appointed High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina. | ||

| 1991 | ||

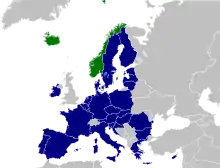

| Iceland is part of the EU market via the European Economic Area and the Schengen Area. Although previously opposed to the idea of membership, it made an application in 2009 due to its economic collapse. From 2010 to 2013 Iceland was working on its accession, when it froze the process. | ||

| 1991 | The European Union has the Enhanced Strategic Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with Kazakhstan, its first with a Central Asian country. The EU is also the largest foreign investor in Kazakhstan, representing over 50% of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Kazakhstan.[142] The EU-Kazakhstan Cooperation Council is a ministerial-level meeting.[143] | |

| Liechtenstein is part of the EU market via the European Economic Area and the Schengen Area. | ||

| 1991 | ||

| Monaco co-operates with the EU in aspects such as the Schengen Area and uses the euro. | ||

| 2006 | Montenegro is an official candidate for the EU, and has applied for EU membership on 15 December 2008. Accession negotiations started on 29 June 2012. | |

| Norway is part of the EU market via the European Economic Area and the Schengen Area. | ||

| San Marino co-operates with the EU in aspects such as the Schengen Area and uses the euro. | ||

| Serbia is an official candidate for the EU, and has applied for EU membership on 22 December 2009. Accession negotiations started on 21 January 2014. | ||

| Ambassador-level relations.[144] | ||

| Switzerland does not participate in the EEA, but does co-operate through bilateral treaties similar to the EEA and is part of the Schengen Area. | ||

| Turkey is an official candidate for the EU, and has applied for EU membership on 14 April 1987. Accession negotiations started on 3 October 2005. Full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey have been effectively suspended since 2019.

On 18 July 2023, the EU decided not to restart full membership negotiations with Turkey.[145] | ||

| 1991 | ||

| 2018 | ||

| 1992 | ||

| The Vatican, as a unique state, does not participate in most EU projects but does use the euro. |

Partly recognised states

| Country | Formal relations began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Limited recognition from 2008 | Kosovo is not recognised by all EU members and therefore cannot have official contractual relations with EU. Yet it still maintains relations with the EU and has been recognised by the EU as a country with a European perspective. | |

| None | Northern Cyprus is not recognised by the EU and is a serious dispute for Cyprus and Turkish membership. The EU is committed to Cypriot reunification. |

ACP countries

The European Union's member-states retain close links with many of their former colonies and since the Treaty of Rome there has been a relationship between the Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries in the form of ACP-EU Development Cooperation including a joint parliamentary assembly.

The EU is also a leading provider of humanitarian aid, with over 20% of aid received in the ACP coming from the EU budget or from the European Development Fund (EDF).[146]

In April 2007 the Commission offered ACP countries greater access to the EU market; tariff-free rice exports with duty- and quota-free sugar exports.[147] However this offer is being fought by France who, along with other countries, wish to dilute the offer.[148]

There are questions as to whether the special relationship between the ACP group and the European Union will be maintained after the coming to the end of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement Treaty in 2020. The ACP has begun looking into the future of the group and its relationship to the European Union. Independent think tanks such as the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) have also presented various scenarios for the future of the ACP group in itself and in relation to the European Union.[149]

The European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) aims at bringing Europe and its neighbours closer.

International organizations

The Union as a whole is increasingly representing its members in international organisations. Aside from EU-centric organisations (mentioned above) the EU, or the Community, is represented in a number of organisations:

- full rights member: the G8;,[150][151] the World Trade Organization;

- partner: the International Development Association; Pacific Islands Forum; the Pacific Community (SPC)

- dialogue member: the ASEAN Regional Forum, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

- observer: the United Nations, the Organization of American States, the Council of the Baltic Sea States; the Australia Group; the European Organization for Nuclear Research; the Food and Agriculture Organization, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the G10, the Non-Aligned Movement; Nuclear Suppliers Group; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East; and the Zangger Committee[152]

The EU is also one of part of the Quartet on the Middle East, represented by the High Representative.[153] At the UN, some officials see the EU moving towards a single seat on the UN Security Council.[154]

The European Union is expected to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights (the convention). In 2005, the leaders of the Council of Europe reiterated their desire for the EU to accede without delay to ensure consistent human rights protection across Europe. There are also concerns about consistency in case law – the European Court of Justice (the EU's supreme court) is already treating the convention as though it was part of the EU's legal system to prevent conflict between its judgements and those of the European Court of Human Rights (the court interpreting the convention). Protocol No.14 of the convention is designed to allow the EU to accede to it and the Treaty of Lisbon contains a protocol binding the EU to joining. The EU would not be subordinate to the council, but would be subject to its human rights law and external monitoring as its member states are currently. It is further proposed that the EU join as a member of the Council once it has attained its legal personality in the Treaty of Lisbon.[155][156]

Where the EU itself isn't represented, or when it is only an observer, the EU treaties places certain duties on member states;

1. Member States shall coordinate their action in international organisations and at international conferences. They shall uphold the Union's positions in such forums. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy shall organise this coordination.

In international organisations and at international conferences where not all the Member States participate, those which do take part shall uphold the Union's positions.

2. In accordance with Article 24(3), Member States represented in international organisations or international conferences where not all the Member States participate shall keep the other Member States and the High Representative informed of any matter of common interest.

Member States which are also members of the United Nations Security Council will concert and keep the other Member States and the High Representative fully informed. Member States which are members of the Security Council will, in the execution of their functions, defend the positions and the interests of the Union, without prejudice to their responsibilities under the provisions of the United Nations Charter.

When the Union has defined a position on a subject which is on the United Nations Security Council agenda, those Member States which sit on the Security Council shall request that the High Representative be invited to present the Union's position.

Foreign relations of member states

Further reading

- The Role of the EU in the South Caucasus. Articles in the Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 35-36

- Butler, Graham; Wessel, Ramses A (2022). EU External Relations Law: The Cases in Context. Oxford: Hart Publishing/Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781509939695.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union" – via Wikisource.

- ↑ TFEU Article 218(2); see Wathelet, Melchior. "ECLI:EU:C:2015:174 European Commission v Council of the European Union". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ "European Peace Facility". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- 1 2 "Taking Europe to the world: 50 years of the European Commission's External Service" (PDF).

- ↑ "EU commission 'embassies' granted new powers". euobserver.com. 21 January 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ EU envoy to US flaunts new powers, EU Observer 11 August 2010

- ↑ EU foreign ministers approve diplomatic service, EU Observer 27 July 2010

- ↑ "European Commission Delegations: Interaction with Member State Embassies". 8 December 2008. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Local offices in EU member countries". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Council delegations

- ↑ "Joint consular work to reinforce 'EU citizenship'". euobserver.com. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Algeria – Trade – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. 30 August 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ↑ Müller-Jentsch, Daniel (2005). Deeper integration and trade in services in the Euro-Mediterranean region : southern dimensions of the European Neighborhood Policy. European Commission, World Bank, World Bank/European Commission Programme on Private Participation in Mediterranean Infrastructure. Washington, DC: World Bank. ISBN 0-8213-5955-X. OCLC 56111766.

- ↑ Algeria, European Commission

- ↑ "Bahrain and the EU | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Joint Letter to the European Union Ahead of Meeting With Bahraini Delegation". Human Rights Watch. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ "Kuwait and EU". EEAS. 5 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "The European Union and Qatar | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Council of EU – Newsroom". newsroom.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "EEAS Saudi Arabia and EU". EEAS. 5 March 2022.

- ↑ "EU trade relations with Gulf region". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "EEAS Saudi Arabia and EU". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ Bianco, Cinzia (26 October 2021). "Power play: Europe's climate diplomacy in the Gulf – European Council on Foreign Relations". ECFR. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "About | EU-GCC Clean Energy Technology Network". www.eugcc-cleanergy.net. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "EEAS Saudi Arabia and EU". saudi-arabia/european-union-and-saudi-arabia_en?s=208. 5 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "EU-EGYPT PARTNERSHIP PRIORITIES 2017–2020" (PDF). 16 June 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "EU trade relations with Egypt". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Egypt, European Commission

- 1 2 3 4 Mohammed, Khogir (January 2018). "The EU Crisis Response in Iraq: Awareness, local perception and reception" (PDF). Middle East Research Institute.

- ↑ "Skirting U.S. sanctions, Europeans open new trade channel to Iran". Reuters. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "EU trade relations with Iran". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Iran – Trade – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 "EU trade relations with Israel". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "The Middle East Peace Process". European Union. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- ↑ "EURO-MEDITERRANEAN AGREEMENT" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Communities.

- ↑ "EU Eyes Exports from Israeli Settlements – Businessweek". Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "EU court strikes blow against Israeli settlers". euobserver.com. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Sadaka. "The EU and Israel" (PDF). p. 1. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ↑ Council of the European Union, "17218/09 (Presse 371)" (PDF), Press release, 2985th Council meeting on Foreign Affairs, Press Office, retrieved 2 August 2011

- ↑ Council of the European Union, "17835/10 (Presse 346)" (PDF), Press release, 3058th Council meeting on Foreign Affairs, Press Office, retrieved 2 August 2011

- 1 2 3 "EU trade relations with Jordan". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "The European Union and Kuwait | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "EU trade relations with Lebanon". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Dandashly, Assem (2022). Routledge handbook of EU-Middle East relations. Dimitris Bouris, Daniela Huber, Michelle Pace. Abingdon, Oxon. pp. 321–330. ISBN 978-1-000-47521-0. OCLC 1253437957.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 "EU trade relations with Libya". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Szabó, Kinga Tibori. LIBYA AND THE EU. Budapest: Central European University. ISBN 9638724560.

- ↑ Libya, European Commission

- ↑ Developments in Libya: an overview of the EU's response, European Commission

- ↑ "Libya/EU: Conditions remain 'hellish' as EU marks 5 years of cooperation agreements". Amnesty International. 31 January 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Italy-Libya agreement: Five years of EU-sponsored abuse in Libya and the central Mediterranean | MSF". Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ The European Union and North Africa : prospects and challenges. Adel Abdel Ghafar. Washington, D.C. 2019. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8157-3696-7. OCLC 1083152695.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe - A Global Strategy for the European Union's Foreign And Security Policy" (PDF). June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "EU trade relations with Morocco". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 "The European Union and Saudi Arabia". Archived from the original on 19 April 2022.

- ↑ "Council of EU – Newsroom". newsroom.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- 1 2 Allen, D. and Pijpers, A. (1984), p 44.

- ↑ Irish Aid (17 December 2007). "Minister Kitt pledges additional assistance for Palestinians at Paris Donor Conference". Government of Ireland. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (17 November 2009). "Too early to recognize Palestinian state: Bildt". The Local. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Office of the European Union Representative West Bank and Gaza Strip. "The Role of the Office of the European Union Representative". European Union. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Permanent Observer Mission of Palestine to the United Nations. "Palestine Embassies, Missions, Delegations Abroad". Palestine Liberation Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Allen, D.; Pijpers, A. (1984). European foreign policy-making and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 69. ISBN 978-90-247-2965-4.

- ↑ Katz, J.E. "The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)". EretzYisroel. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ "In Cairo speech, EU's Catherine Ashton very critical of Israeli policies". Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ McCarthy, Rory (1 December 2009). "East Jerusalem should be Palestinian capital, says EU draft paper". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (13 July 2009). "Israel rejects EU call for Palestinian state deadline". Hurriyet Daily News. Hurriyet Gazetecilik A.S. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (28 August 2011). "Palestinians see progress in EU stance on UN bid". France 24. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Keinon, Herb (28 August 2011). "Israel looks to influence text of PA statehood resolution". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ↑ "EU trade relations with Palestine". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Qatar and the EU". Archived from the original on 1 July 2021.

- ↑ "Qatar – Mapping European leverage in the MENA region – ECFR". ecfr.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Saudi Arabia and the EU | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ↑ Gündoğar, Sabiha Senyücel. Saudi Arabia's Relations with the EU and Its Perception of EU Policies in MENA | PODEM.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia – Mapping European leverage in the MENA region – ECFR". ecfr.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 South Africa, European External Action Service

- ↑ Bilateral relations South Africa, European Commission

- ↑ "South Sudan".

- 1 2 3 4 "The European Union and South Sudan | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 Dvornichenko, Darina; Barskyy, Vadym (June 2020). "The Eu and Responsibility to Protect: Case Studies on the Eu's Response to Mass Atrocities in Libya, South Sudan and Myanmar". InterEULawEast: Journal for the International and European Law, Economics and Market Integrations. 7 (1): 117–138. doi:10.22598/iele.2020.7.1.7. ISSN 1849-3734. S2CID 225790792.

- ↑ "International Partnerships – Sudan".

- 1 2 "The European Union and Sudan | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ↑ "Sudan". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ↑ "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on Sudan". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ↑ "Sudan: Statement by the High Representative/Vice President Josep Borrell on the latest situation | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kizilkan, Zelal Başak (2019). "Changing Policies of Turkey and the EU to the Syrian Conflict". Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi. 33 (1): 321–338.

- ↑ "Timeline – EU response to the Syrian crisis". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "EU trade relations with Tunisia". policy.trade.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Tunisia, European Commission

- 1 2 "The European Union and the United Arab Emirates | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 "UAE – Mapping European leverage in the MENA region – ECFR". ecfr.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "EU Parliament urges UAE to free imprisoned human rights activists". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ "Arab Parliament rejects EU Parliament's resolution on human rights in UAE". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters (7 February 2017). "EU to uphold Morocco farm accord despite Western Sahara ruling". Reuters. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Morocco deals don't cover Western Sahara, EU lawyer says". euobserver.com. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "The EU's Morocco problem". politico.eu. 23 December 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Dudley, Dominic. "European Court Dismisses Morocco's Claim To Western Sahara, Throwing EU Trade Deal into Doubt". forbes.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "EU-Yemen relations | EEAS Website". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ↑ Durac, Vincent (2022). Routledge handbook of EU-Middle East relations. Dimitris Bouris, Daniela Huber, Michelle Pace. Abingdon, Oxon. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-000-47521-0. OCLC 1253437957.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Made in Europe, bombed in Yemen: How the ICC could tackle the responsibility of arms exporters and government officials" (PDF).

- ↑ "European Union – EEAS (European External Action Service) | EU Relations with Barbados". Europa (web portal). 19 June 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- 1 2 EU And Latin America Seek New Ways Of Cooperation playfuls.com Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ CAN, EU to start trade talks in first quarter of 2007 xinhuanet.com

- ↑ EU to announce $1.14 bln aid program for Central America keralanext.com

- ↑ "EU-US Facts & Figures". European Union External Action. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ↑ "The European Union and the United States: Global Partners, Global Responsibilities' " (PDF). Delegation of the European Union to the United States. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- 1 2 "EU-ASEAN commemorative summit, 14 December 2022". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ Burma will not take Asean chair BBC News

- ↑ Australia, European External Action Service

- ↑ Bilateral relations Australia, European Commission

- ↑ Blenkinsop, Philip (7 December 2022). "Australia targets EU trade deal in first half of 2023 – minister". Reuters. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ Bilateral relations China, European Commission

- ↑ EU replaces US as biggest trading partner of China(09/15/06) china-embassy.org

- ↑ With big order, China gives Airbus a boost iht.com

- 1 2 3 Sutter, Robert G. (2008) Chinese Foreign Relations Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p.340-342

- ↑ Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office, Brussels Official Website, retrieved 14 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 EU-Japan: overall relationship, European External Action Service

- 1 2 3 Bilateral relations Japan, European Commission Directorate General for Trade

- ↑ "Malaysia-European Union Bilateral Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- 1 2 Christoph Marcinkowski; Ruhanas Harun; Constance Chevallier-Govers. "Malaysia and the European Union: A Partnership for the 21st Century". Centre D'Etudes Sur La Securite Internationale Et Les Cooperations Europeennes. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysia". European External Action Service. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysia-European Union Free Trade Agreement (MEUFTA)". Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Malaysia. 18 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ New Zealand, European External Action Service

- ↑ Bilateral relations New Zealand, European Commission

- ↑ "EU trade deal on track for formal signing this year". NZ Herald. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ↑ "Pakistan – Trade – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- 1 2 Republic of Korea, European External Action Service

- ↑ Bilateral relations Korea, European Commission

- 1 2 "European Commission – South Korea Briefing". European Commission. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ↑ "FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT for Trade and Cooperation between the European Community and its Member States, on the one hand, and the Republic of Korea, on the other hand" (PDF). European Commission. 30 March 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ↑ Political relations, EU delegation to Korea

- ↑ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Republic of Korea". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Korolev, Alexander S. (2023). "Political and Economic Security in Multipolar Eurasia". China and Eurasian Powers in a Multipolar World Order 2.0: Security, Diplomacy, Economy and Cyberspace. Mher Sahakyan. New York: Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-003-35258-7. OCLC 1353290533.

- 1 2 "The EU and the countries of Central Asia held their High-level Political and Security Dialogue in Ashgabat on 9 July 2018". EU External Action.

- ↑ "Central Asia, EU discuss cooperation, new strategy". Astana Calling.

- ↑ "Press corner". European Commission – European Commission.

- 1 2 "Opportunities for more cooperation discussed in the EU-Central Asia ministerial call". EEAS.

- 1 2 "Astana Hosts First Regional Central Asia-EU High-Level Meeting". The Astana Times. 27 October 2022.

- ↑ "BOMCA". Border Management Programme in Central Asia.

- ↑ "CADAP". Central Asia Drug Action Programme.