| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

.png.webp) |

|

Forensic palynology is a subdiscipline of palynology (the study of pollen grains, spores, etc.), that aims to prove or disprove a relationship among objects, people, and places that may pertain to both criminal and civil cases.[1] Pollen can reveal where a person or object has been, because regions of the world, countries, and even different parts of a single garden will have a distinctive pollen assemblage.[2] Pollen evidence can also reveal the season in which a particular object picked up the pollen.[3]

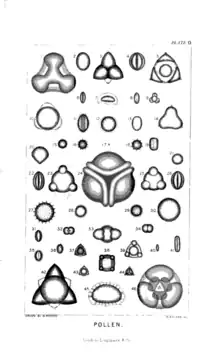

Palynology is the study of palynomorphs - microscopic structures of both animal and plant origin that are resistant to decay. This includes spermatophyte pollen, as well as spores (fungi, bryophytes, and ferns), dinoflagellates, and various other organic microorganisms - both living and fossilized.[4] There are a variety of ways in which the study of these microscopic, walled particles can be applied to criminal forensics.

In areas such as New Zealand, where the demand for this field is high, forensic palynology has been used as evidence in many different case types that range anywhere from non-violent to extremely violent crimes.[5] Pollen has been used to trace activity at mass graves in Bosnia,[6] pinpoint the scene of a crime,[5] and catch a burglar who brushed against a Hypericum bush during a crime.[7] Because pollen has distinct morphology and is relatively indestructible, it is likely to adhere to a variety of surfaces often without notice and has even become a part of ongoing research into forensic bullet coatings.[8]

Present status

Forensic Palynology is an evolving forensic science application. And is mostly utilized in countries such as New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom.[1] It is relatively "small, disparate, and fragmented" compared to the other approaches, thus, there is no thorough guide to achieve the best practice in forensic palynology.[9] Moreover, there is a limit in forensic palynologists as most skilled palynologists do not enter the forensic palynology field.[10] As becoming a Forensic Palynologist requires rigorous training and education, one must attain a Ph.D. with sufficient background in studies such as forensic science, botany, ecology, geography, and climatology.[11] Most importantly they must receive training in the field of quaternary science.[11]

Duties

In terms of criminal investigation, forensic palynologist services are requested from cases such as forgery, rape, homicide, genocide, terrorism, drug dealing, assault, and robbery.[1] It usually consist of a single individual who works with the polynomial case. Of course, the palynologist could still consult other professionals. Furthermore, the palynologist should be given significant information as there is only one person handling the analysis of the samples. Important duties to note is that they ensure that all paperwork is dated, signed, filed and archived in order to maintain good records. Forensic Palynologists usually visit the crime scene to survey the vegetation. For example, identify plants and their characteristics and qualities ( size, vigor...) and obtain plant samples to allow for analysis like ground sampling. Scrubbing, scraping, washing is essential for retrieval of palynomorphs from various materials. And utilize other methods like police photographers, cartographers, and botanists. It is vital for the Forensic Palynologist to visit the crime scene before the Crime Science Investigators (CSI) or Scenes of crime Officers (SOCOs) to avoid disturbance of environmental evidence and contamination.[9]

Advantages

Pollen and similar spores are generally less than 50 microns across, resulting in their easy and unnoticeable transportation.

Pollen grains have a variety of shapes, sizes, colors, structures, and numbers identification keys exist as a reference. Large-scale collections of pollen specimens that reside in museums and university herbaria also serve as a resource for forensic palynologists to identify and classify the samples they collect.

A sample of pollen from a crime scene can help to identify a specific plant species that may have had contact with a victim, or point to evidence that does not ecologically belong in the area. A pollen assemblage is a sample of pollen with a variety of plant species represented. Identifying those species and their relative frequency can point to a specific area or time of year. This could aid in the determination of whether the scene where the pollen was found was the primary scene or secondary scene. Pollen is made in great numbers, by a large variety of plants, and it is designed to be dispersed (either via wind, insect, or another method) throughout the immediate environment. Pollen can also be found in soil, clothing, hair, drugs, stomach contents, ropes, and rock which are places where it would be difficult for the suspect to remove because of pollen's adhesion properties.[5][4] In some cases, where the pollen of a plant is absent, fungi and fungal spores may be able to detect a plant's presence at the site.[12] There have been cases where the presence of rarely reported fungi and fungal spores have helped identify information in forensic cases.[12]

Disadvantages

One of the main disadvantages in this field is the lack of trained specialists.[4] As of 2008, there are no academic centers or training facilities for the use of pollen in forensics in the U.S.[13][4] This is crucial because of the expertise required to identify palynomorphs and to apply the data to geolocation information.[14] Many things could go wrong and invalidate any samples collected, especially if the personnel handling them is not experienced. On the subject of experience, contamination is another major problem that can invalidate the use of a sample as evidence; therefore, it is important that samples are collected early on with collection sites identified depending on the case.[15]

Limited access to international databases can also prove to be an issue when it comes time for the analyst to identify pollen evidence to a specific family or genus of plants.[16] Currently, a database from Austria called PalDat exists but there are no known databases to exist in North America.[5]

Methods

Sample Collection

Because pollen can be easily picked up by anyone, it is important that pollen samples are collected as soon as possible to prevent contamination from outside sources.[13] Samples then need to be prepared and placed on slides in order to fully be safe from contamination.[13] The process of preparing the samples and identifying them is time-consuming. When collecting a sample, it should be paired with site surveys and photos of the scene to provide context for later uses.[1] For example, if the pollen evidence is used in court, then the additional context would be useful.

Sample collection methods will vary depending on the case investigation and on the collector.[1] Due to the lack of palynologists in the forensic field, other forensic scientists that are present may have to collect the samples.[1] This raises issues in terms of the quality of the sample, since collection sites for the sample should be determined depending on the case.[1] Discussion with the investigation team is necessary in order to establish the best sampling method.[1]

When collection sites have been determined, samples can be retrieved with clean instruments and placed into tightly sealed, sterile containers.[1] Examples are "sterile zip-lock plastic bags, or screw-top plastic (in preference to glass) containers."[1] After each sample, instruments should be thoroughly cleaned or replaced to prevent contamination.[1] In cases, where collection is by hand, gloves should be used and replaced after each sample.[1] Samples should be labeled and sample history documentation should be maintained to keep track of the people who have had access to the sample.[1]

Analysis

Analyzing the samples, once the palynomorphs have been extracted, will allow for identification, which can then be used in a forensic case to relate a person or object to a crime scene, or even to determine whether the scene at which the pollen was found was the primary or the secondary scene.[13]

Samples are chemically processed with a mix of acids, sodium hydroxide, acetic anhydride with water washes in between.[12] They are then neutralized, and the extracts are stained and mounted onto slides for microscopic examination.[12] This helps in identification with the help of available reference collections to make comparisons on the pollen's characteristics.[13] The scanning electron microscope (SEM) has been used traditionally since the 1970s for primary identification of palynomorphs, but is very time-consuming, tedious, and not ideal for routine analysis.[4]

Compared to the SEM, semi-automated pollen grain imaging techniques such as Transmitted Light Microscopy (TLM), Widefield fluorescent method, and Structured illumination (Apotome) were found to have a higher speed and accuracy when it came to the identification of pollen spores.[4]

DNA Barcoding is another method used to differentiate between pollen grains by comparing their DNA sequences.[4] A pollen grain of 10 micrometers in length is required.[4] Once the sample is collected and prepared, genetic markers are placed, then the DNA is isolated, and finally the DNA is sequenced, usually through high throughout sequencing (HTS).[4] HTS is faster and less expensive than traditional methods for DNA barcoding.[4]

Case Examples

Austria, 1959

One of the earliest document cases in which pollen plays a key role took place in Austria. A man went missing, and was presumed murdered, but no body was found. The authorities had arrested a suspect, who had motive for the murder, but did not have a body or confession, and the case stalled. A search of the suspect's belongings yielded a pair of muddy boots. The mud was sampled and given to Wilhelm Klaus, at the University of Vienna's Paleobotany Department, for analysis. Dr. Klaus found modern pollen from a variety of species, including spruce, willow, and alder. He also found fossilized hickory pollen grains, from a species long extinct. There was only one area of the Danube River Valley that hosted those living plants, and had Miocene-aged rock deposits that would contain the fossilized species. When the suspect was presented with this information, he willingly confessed and lead authorities to the sites of both the murder and the body, both of which were inside the region indicated by Dr. Klaus.[5][17]

United States, 1970

The first cases that involved forensic palynology in the United States was in 1970, where Honeybee pollination studies were issued. During this time honey pollen analysis began growing as the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), insured beekeepers a higher world market price for their honey. Under the premisses that the honey was produced on USA grounds. Thus, honey samples were sent for pollen analysis, where confirmation that the honey was produced in the USA was concluded or not. Generally, most of the cases during this time involved lawsuits concerning beekeepers. For example, a Michigan beekeeper arose suspect of importing beehives from the southeastern USA that weren't inspected for mites. This led to the USDA inspecting honey samples where it was concluded that they were imported from the Southeastern region of USA. Due to that the honey contained floral types common to the Southeastern region and not found in Michigan.[18]

United Kingdom, 1993

An example concerning Forensic Palynology in the United Kingdom, took place during 1993 handled by Patricia Wiltshire.[19] Where it involved a murder case in which the body was laid on soil that preserved pollen. Wiltshire then found traces of walnut pollen in the soil and suspect's shoes, however, the walnut pollen found was unusual as there was no walnut site nearby. However, It was later discovered that a walnut tree was cut down thirty years before and the walnut pollen remained. the pollen was then analyzed and linked to the suspect in the crime scene. Thus, the walnut pollen provided a significant role solving the case.[20]

New Zealand, 2005

After a home invasion, two burglars brushed past a Hypericum bush outside of the house. One of the burglars was brought in as a suspect, but all evidence was circumstantial, and the man did not confess. Analysis of his clothes revealed the Hypericum pollen. The presence of pollen is ubiquitous, but in this case, the pollen was clumped onto the clothing (rather than dusted) and did not seem to be simply the result of air dispersal. It was ultimately concluded that "the clothes had so much Hypericum pollen on them that they had to have been in direct and intimate contact with a flowering bush."[7]

United States, 2015

A modern application of forsenic palynology occurred in 2015, in the city of Boston, Massachusetts. A body of a young female child was discovered by law enforemcent in the Boston Harbour, but no identifying features remained as the body was in the late stages of decomposition. Investigators submitted samples taken from the clothes of the victim, a blanket found with the body, as well as a small amount of recovered hair to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection directorate laboratory in Houston, Texas, for pollen analysis. The report from the submitted samples provided investigators with information they could use to identify the unknown victim.[21]

The pollen assemblage created from the submitted samples indicated the vicitm was in the north-eastern United States before her death. The individual taxa of plant species observed in the assemblage also indicated that the victim lived in, or spent much of her time in, a developed, urban environment. The assemblage also captured pollen of the Lebanese cedar tree (Cedrus libani), native to the Eastern Mediterranean region of Europe. The species of cedar observed in the assemblage was thought by investigators to most likely be from an ornamental piece in a park or other conservation area. This is when the investigators discovered individuals of the Lebanese cedar tree in the Arnold Arboretum, a public park that is a part of Harvard University.[21]

Investigators then asked around the neighborhoods surrounding the arboretum, and a tip led them to a resident who, after questioning, admitted that her boyfriend at the time had abused the child, which resulted in the child's death. The man who murdered the child was sentenced to serve a minimum of 20 years for second degree murder. The mother's involvemnt in the crime is not reported, though she served 2 years probation for accessory after a plea deal for providing information about her then boyfriend who had committed the act.[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Mildenhall, D. C.; Wiltshire, P. E. J.; Bryant, V. M. (22 November 2006). "Forensic palynology: Why do it and how it works". Forensic Science International. Forensic Palynology. 163 (3): 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.07.012. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 16920303.

- ↑ Vaughn M. Bryant. "Forensic Palynology: A New Way to Catch Crooks". Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- ↑ Robert Stackhouse (17 April 2003), "Forensics studies look to pollen", The Battalion, archived from the original on 23 April 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alotaibi, Saqer S.; Sayed, Samy M.; Alosaimi, Manal; Alharthi, Raghad; Banjar, Aseel; Abdulqader, Nosaiba; Alhamed, Reem (1 May 2020). "Pollen molecular biology: Applications in the forensic palynology and future prospects: A review". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 27 (5): 1185–1190. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.02.019. ISSN 1319-562X. PMC 7182995. PMID 32346322.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mildenhall, Dallas (2008). "Civil and criminal investigations. The use of spores and pollen". SIAK-Journal − Zeitschrift für Polizeiwissenschaft und polizeiliche Praxis (4): 35–52. doi:10.7396/2008_4_E.

- ↑ Peter Wood (9 September 2004), "Pollen helps war crime forensics", BBC News, retrieved 4 January 2010

- 1 2 D. Mildenhall (2006), "Hypericum pollen determines the presence of burglars at the scene of a crime: An example of forensic palynology", Forensic Science International, 163 (3): 231–235, doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.028, PMID 16406430

- ↑ Sermon, Paul A.; Worsley, Myles P.; Cheng, Yu; Courtney, Lee; Shinar-Bush, Verity; Ruzimuradov, Olim; Hopwood, Andy J.; Edwards, Michael R.; Gashi, Bekim; Harrison, David; Xu, Yanmeng (September 2012). "Deterring gun crime materially using forensic coatings". Forensic Science International. 221 (1–3): 131–136. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.04.021. PMID 22608265.

- 1 2 Wiltshire, Patricia E. J. (2016). "Protocols for forensic palynology". Palynology. 40 (1): 4–24. doi:10.1080/01916122.2015.1091138. ISSN 0191-6122. JSTOR 24741963. S2CID 131148113.

- ↑ Bryant, V. M. (1 January 2013), "USE OF QUATERNARY PROXIES IN FORENSIC SCIENCE | Analytical Techniques in Forensic Palynology", in Elias, Scott A.; Mock, Cary J. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science (Second Edition), Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 556–566, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53643-3.00363-0, ISBN 978-0-444-53642-6, retrieved 4 March 2022

- 1 2 Green, Elon (17 November 2015). "How Pollen Solves Crimes". The Atlantic. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Hawksworth, David L.; Wiltshire, Patricia E. J.; Webb, Judith A. (1 July 2016). "Rarely reported fungal spores and structures: An overlooked source of probative trace evidence in criminal investigations". Forensic Science International. Special Issue on the 7th European Academy of Forensic Science Conference. 264: 41–46. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.02.047. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 27017083.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bock, Jane H.; Norris, David O. (1 January 2016), Bock, Jane H.; Norris, David O. (eds.), "Chapter 10 - Additional Approaches in Forensic Plant Science", Forensic Plant Science, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 129–147, ISBN 978-0-12-801475-2, retrieved 2 March 2022

- ↑ Riley, Kimberly C.; Woodard, Jeffrey P.; Hwang, Grace M.; Punyasena, Surangi W. (1 October 2015). "Progress towards establishing collection standards for semi-automated pollen classification in forensic geo-historical location applications". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 221: 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.06.005. ISSN 0034-6667.

- ↑ Wiltshire, Patricia E. J. (2 January 2016). "Protocols for forensic palynology". Palynology. 40 (1): 4–24. doi:10.1080/01916122.2015.1091138. ISSN 0191-6122. S2CID 131148113.

- ↑ Alotaibi, Saqer S.; Sayed, Samy M.; Alosaimi, Manal; Alharthi, Raghad; Banjar, Aseel; Abdulqader, Nosaiba; Alhamed, Reem (May 2020). "Pollen molecular biology: Applications in the forensic palynology and future prospects: A review". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 27 (5): 1185–1190. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.02.019. ISSN 1319-562X. PMC 7182995. PMID 32346322.

- ↑ "Forensic Palynology: A New Way to Catch Crooks". http. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Bryant, Vaughn M.; Jones, Gretchen D. (22 November 2006). "Forensic palynology: Current status of a rarely used technique in the United States of America". Forensic Science International. Forensic Palynology. 163 (3): 183–197. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.021. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 16504436.

- ↑ Laurence, Andrew R.; Bryant, Vaughn M. (2014), "Forensic Palynology", in Bruinsma, Gerben; Weisburd, David (eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 1741–1754, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_169, ISBN 978-1-4614-5690-2, retrieved 5 March 2022

- ↑ "Forensic science: How pollen is a silent witness to solving murders". BBC News. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 Laurence, Andrew R.; Bryant, Vaughn M. (1 September 2019). "Forensic palynology and the search for geolocation: Factors for analysis and the Baby Doe case". Forensic Science International. 302: 109903. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.109903. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 31400618. S2CID 199527472.