| Fort Granville | |

|---|---|

| Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, USA | |

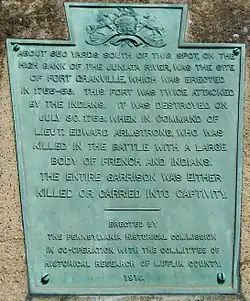

1916 state historical marker near Lewistown | |

Fort Granville Approximate location of Fort Granville in Pennsylvania | |

| Coordinates | 40°35′18″N 77°36′5.89″W / 40.58833°N 77.6016361°W |

| Type | Fort |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1756 |

| In use | January-August, 1756 |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Captain James Burd Captain Edward Ward Lieutenant Edward Armstrong † |

| Garrison | 75 men |

| Designated | 1916 |

Fort Granville was a militia stockade located in the colonial Province of Pennsylvania. Its site was about a mile from Lewistown, in what is now Granville Township, Mifflin County. Active from 1755 until 1756, the stockade briefly sheltered pioneer settlers in the Juniata River valley during the French and Indian War.[1] The fort was attacked on August 2, 1756, by a mixed force of French troops and Native Americans, mostly Lenape warriors. The fort’s garrison surrendered the strongpoint to these attackers, who celebrated their victory and destroyed the stockade.

Background

After the French victory in the Battle of the Monongahela on 9 July 1755, English settlers, who set up farms on Native American lands that they had illegally squatted on drew in hostilities from Native Americans. Native Americans who never legally ceded their land, resorted to hit-and-run tactics on the Pennsylvania frontier. The Native American tribes whose land was underhandedly sold by the Iroquois and the Province of Pennsylvania then entered in alliances with Native Americans from present-day Ohio. This led to the Franco-Indian alliance with Native American Nations who distrusted the Iroquois, the British, and Pennsylvania. The Shawnee and Delaware sought to drive settlers off of land sold out from under the Shawnee by the British and Iroquois in western Pennsylvania.[2] In late 1755, Colonel John Armstrong wrote to Governor Robert Hunter Morris: "I am of the opinion that no other means of defense than a chain of blockhouses along or near the south side of the Kittatinny Mountains from the Susquehanna to the temporary line, can secure the lives and property of the inhabitants of this country."[3]: 557 The provincial government of Pennsylvania decided that a string of forts should be constructed across the province from the Delaware Water Gap to the Maryland line.[4][5]: 186 On 17 December 1755, Capt. George Croghan was issued the order below as signed by Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Fox, Joseph Hughs, and Evan Morgan:

Sir:—You are desired to proceed to Cumberland County and fix on proper places for erecting three stockades, viz.: One back of Patterson's, one upon Kishecoquillas, and one near Sideling Hill; each of them fifty feet square, with Block House on two of the corners, and a Barracks within, capable of lodging fifty men. You are also desired to agree with some proper Person or Persons to oversee the workmen at each Place, who shall be allowed such Wages as you shall agree to give, not exceeding one Dollar per day; and the workmen shall be allowed at the rate of six Dollars per month and their Provisions, till the work is finished.[6]

Location and construction

Instead of constructing the fort at the mouth of the Kishacoquillas Creek, Croghan went up the Juniata River to a site near a spring. The exact location can no longer be determined, as the construction of the Pennsylvania Canal destroyed the spring around 1829.[6] According to historian Walter O'Meara, "This fort was an important link in the chain of strongpoints on the west side of the Susquehanna [River], commanding the point where the Juniata [River] falls through the mountains."[1] Governor Morris planned the construction of Fort Pomfret Castle, Fort Granville, Fort Shirley, and Fort Lyttleton as the westernmost line of defense of the Pennsylvania frontier.[7]: 385

Croghan began construction in December 1755, and in January 1756, the fort was named by Governor Robert Hunter Morris in honor of John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville.[7]: 383 The final construction was square, with sides measuring eighty-three paces (between 207.5 and 415 feet), with a bastion at each of the four corners. An important natural feature of the fort site was a ravine which, since the fort's slope had not been graded to form a glacis, provided cover for the enemy forces who later captured the fort.[7]: 383

In February 1756, Governor Morris described the fort to General William Shirley:

- "15 miles northeast of Fort Shirley, near the mouth of a Branch of the Juniata called Kishequokilis, a third Fort is erected, which I have called Fort Granville. This Fort commands a narrow pass...which is so circumscribed that a few men can maintain it against a much greater number, as the rocks are very High on each side, not above a gunshot assunder, and thus extended for 6 miles, and leads to a considerable settlement upon the Juniata, between Fort Granville and where that River falls into the Susquehanna."[7]: 385

Garrison and supplies

Governor Morris assigned 75 men under the command of Captain James Burd to construct the fort, however by February the garrison was reduced to 41 as detachments were sent to various locations to obtain supplies. Food and ammunition were in short supply, with Burd writing to his lieutenant on 27 February, "Write to Mr. Buchannan to send...one whole barrel of Gun poudder, letting him know that we have not one ounce in store here." On 28 March, Elisha Saltar, Commissary General, reported to Governor Morris that "Fort Granville...is so Badly stor'd with Amunition, not having three rounds per man...Great part of the Souldiers have left their posts & Come to the Inhabitants, particularly from Fort Granville." Soon after this, Captain Burd was promoted to major and transferred to the Third Battalion of the Pennsylvania Provincial Regiment, to begin construction of Fort Hunter and later Fort Halifax and Fort Augusta. Captain Edward Ward was given command of the fort. On 20 May, Ward wrote to Major Burd, "I have but 30 men to garrison This fort at present." By 3 June, there were 39 men listed in the garrison, although some of these were untrained recruits.[7]: 388–89

Two separate reports state that the fort was equipped with two swivel guns, mounted on the bastions.[7]: 389, 393

Siege and capture, 1756

In 1754, the British and Iroquois had sold lands traditionally recognized as belonging to the Shawnee. In response, the Shawnee called on Indian allies from across the Ohio Valley. Delaware and Illinois warriors, along with a small group of French soldiers, joined the Shawnee in their effort to drive off the new interlopers by attacking recently established farms.[8]

By the summer of 1756, the local settlers only left the fort when absolutely necessary due to an increase in the number of sightings of Native Americans intent on reclaiming their land. The combined Native American forces had driven most settlers in the area to Fort Granville. Assistance for the recent settlers arrived under the command of Lieutenant Edward Armstrong (brother of Colonel John Armstrong) with a militia force to protect them during the harvest. Some of this militia was sent south to Tuscarora to help the settlers there.[8]

Around 22 July, some 60 to 70 Indian warriors, including Shawnee, Delaware, and Illinois, appeared outside the fort ready for battle, but the commanding officer declined to engage in hopes they would leave. The Native Americans fired at one man and wounded him but he was able to get back into the fort with no serious injury. A short distance from the river they killed a man named Baskins, burned his house, and took his wife and children captive.[4] They also took Hugh Carrol and his family prisoners.[9]

On 30 July, Captain Edward Ward, commandant at Fort Granville, took all but 24 men out of the fort to protect settlers in Sherman's Valley, leaving Lieutenant Armstrong in command.[6] The Native Americans estimated the number of men remaining in the fort, and on 2 August 100 warriors, along with 55 Frenchmen[6][9] led by Francois Coulon de Villiers[10] (not his brother, Louis Coulon de Villiers, as is often written incorrectly) attacked the fort .[1]

About midnight, Coulon's men succeeded in setting Fort Granville on fire. In his diary account of the fort's capture, Joseph Shippen wrote that "they were putting out the Fire with Clay, having no Water in the Fort."[11] Armstrong was shot while trying to extinguish the fire, and the French commander ordered a suspension of hostilities. Several times, Coulon offered quarter to the defenders for their surrender, but Armstrong refused. He was later shot a second time and died. Shortly after Armstrong's death, Sergeant John Turner surrendered the fort by opening the gates.[9] Following orders from the French commander, Fort Granville was burnt by Captain Jacobs, leader of the Delaware participants.[12][8]

A report published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on 19 August stated:

- "The Enemy took Juniata Creek, and came under its Bank to a Gutt [ravine] (said to be about 12 Feet deep) and crept up till they came within about 30 or 40 Feet of the Fort, where the Shot from our Men could not hurt them: That into that Gutt they carried a Quantity of Pine Knots, and other combustible Matter, which they threw against the Fort, till they made a Pile and Train from the Fort to the Gutt, to which they set Fire, and by that Means the Logs of the Stockade catched, and a Hole was made, through which the Lieutenant and a Soldier were shot, and three others wounded, while they were endeavouring to extinguish the Flames: That the Enemy then called to the Besieged, and told them, they should have Quarter, if they would surrender; upon which, it is said, one John Turner immediately opened the Gates, and they took Possession of the Fort."[7]: 390

The French letter

Before leaving, the French commandant had his troops set up a flagpole with a French flag on it, and "a Shot Pouch, with a written Paper in it." The pouch containing the letter, written in French, was prominently displayed so that it would be found by any British troops sent to the fort. The letter appeared to be from a French woman, saying goodbye to her lover:

- "Don't think that ever I will have any Regard for You, & don't expect ever to get any Mercy from me, for I do not want to see You after You vex me so much...Go away, it is not expedient that you should remain here...think not that I shall cease to persecute you."[12]: 124

At least one historian believes that the letter was intended as a joke, mocking the British military.[11]

Aftermath

The captives (22 soldiers, 3 women, and 5 or 6 children) were divided, and some were taken to Fort Duquesne and then to the Lenape village of Kittanning, including Sergeant John Turner, his wife and stepsons Simon Girty, Thomas Girty, George Girty, and James Girty.[8][13]: 28 There, Captain Jacobs ordered that the sergeant be put to death.[14]: 108 They tied him to a stake and "after having heated several old gun barrels red-hot, they danced around him, and every minute or two, seared and burned his flesh... After tormenting him almost to death, they scalped him, and then held up a lad, who ended his sufferings by laying open his skull with a hatchet."[9][7]: 393 The reasons for Turner's execution are unclear. One source says that it was due to a personal feud with an Indian named Fish whom Turner had killed,[15] but a French report of Fort Granville's capture, found after the capture of Fort Duquesne in 1758, says that Turner was accused of murdering Simon Girty Sr., (Simon Girty's father) in order to marry his widow.[7]: 394 [Note 1]

One prisoner, a man named Barnhold, managed to escape and provided the first eyewitness account of the fort's capture.[7]: 391 The other captives were taken to Fort de Chartres in the Illinois country, where they were ransomed from the Indians by the French officers and local inhabitants. Escorted to New Orleans, they were then repatriated to England and eventually returned to the American colonies.[16]: 239

Analysis of the factors leading to the fort's capture focused on the lack of ammunition and the ravine which allowed French forces to approach the fort unseen. Colonel William Clapham wrote from Fort Augusta on 14 August that he was "well Assured that this Loss was entirely occasioned by a Want of Ammunition, having receiv'd a Letter two or three days ago from Colonel John Armstrong, that they had in that Fort only one Pound of Powder & fourteen Pounds of Lead." In response, Benjamin Franklin reported that the fort had "50 Pound of Powder, and 100 Weight of Lead." Captain Joseph Shippen wrote to his father, Edward Shippen III: "It was a scandalous thing to leave the Gully near Fort Granville just as Nature left it."[7]: 391–92

The French and Indian raid led to retaliation in the form of the Kittanning Expedition, led by Lieutenant Armstrong's brother, Colonel John Armstrong.[1] Thomas Girty, stepson of Sergeant John Turner, was rescued during the raid and provided additional details about the fort's capture.[7]: 393

Fort Granville was not rebuilt, as it was decided that the western line of defense was too widely spaced and difficult to supply. Plans to build Fort Pomfret Castle were scrapped and Fort Shirley and Fort Patterson were abandoned. The line of defense withdrew to Fort Augusta, Fort Hunter, and Fort Halifax.[7]: 392

Legacy

A brass plaque on a stone plinth memorializing the fort's destruction was erected in Lewistown in Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, in 1916 by the Pennsylvania Historical Commission and the Committee on Historical Research of Mifflin County.[17]

A historical marker was erected in 1947 by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.[18]

See also

External links

Notes

- ↑ Information in the French report is only slightly inconsistent with British reports. Dated 23 August 1756, it reports that 27 prisoners were taken and four of the fort's garrison were killed and scalped. It states that the attacking force consisted of 32 Native Americans and 23 French soldiers. On capturing the fort, the report says that the French found two swivel guns and 100 barrels of gunpowder, along with six months' rations.[7]: 393–94

References

- 1 2 3 4 O'Meara, Walter (1965). Guns at the Forks. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. p. 174.

- ↑ "Commerce and Conflict on the 18th-Century frontier," American Archaeology Magazine, Fall 2013, Vol. 17 No. 3

- ↑ Thomas Lynch Montgomery, ed. Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania, vol 1, Harrisburg, PA: W.S. Ray, state printer, 1916

- 1 2 Legends of America: Fort Granville, Pennsylvania, 2023

- ↑ Waddell, Louis M. "Defending the Long Perimeter: Forts on the Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. Frontier, 1755-1765.” Pennsylvania History, 62:2(1995):171-195.

- 1 2 3 4 Jordan, John Woolf (1913). A History of the Juniata Valley and Its People. New York, NY: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 247–250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hunter, William Albert. Forts on the Pennsylvania Frontier: 1753–1758, (Classic Reprint). Fb&c Limited, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Clarence M. Busch, Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania, Vol. 1, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Uriah James; Egle, William Henry (1889). History of the Early Settlement of the Juniata Valley. Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company. p. 67.

- ↑ Gilbert Din, "Francois Coulon de Villiers: More Light on an Illusive Historical Figure," Louisiana History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2000; pp. 345–357

- 1 2 James P. Myers, "The Fall of Fort Granville, 'The French Letter,' and Gallic Wit on the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1756." Pittsburgh History, vol. 79, Winter 1996-97; pp. 154-59

- 1 2 Rupp, Israel Daniel (1846). History and Topography of Northumberland, Huntingdon, Mifflin, Centre, Union, Columbia, Juniata and Clinton Counties, PA. Lancaster, PA: Gilbert Hills. p. 105.

- ↑ Butts, Edward. Simon Girty: Wilderness Warrior. Canada: Dundurn, 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Robert Walter. History of Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: Waterman, Watkins, 1883.

- ↑ Earl Nicodemus, "The Mostly True Story of Simon Girty," September 11, 2017

- ↑ "The Illinois Country, 1673-1818." in Clarence Alvord, ed. The Centennial History of Illinois, vol 1. Illinois Centennial Commission: A. C. McClurg, 1922.

- ↑ William Fischer, "Fort Granville plaque," Historical Marker Database, February 8, 2012

- ↑ William Fischer, "Fort Granville marker," Historical Marker Database, June 16, 2016