| Fort Hampton | |

|---|---|

| Athens, Alabama in United States | |

Historical marker for Fort Hampton | |

Fort Hampton  Fort Hampton | |

| Coordinates | 34°48′23″N 87°11′55″W / 34.80639°N 87.19861°W |

| Type | Log buildings |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Controlled by | Private |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Site occupied by private home |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1810 |

| Built by | United States Army |

| In use | 1810–1817 |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 |

Fort Hampton was a collection of log buildings and stables built in present-day Limestone County, Alabama, on a hill near the Elk River. It was named for Brigadier General Wade Hampton by Alexander Smyth, and once complete in the winter of 1810 both men visited the site.[1][2] The fort was originally built to deter Americans from settling in Chickasaw territory, then was garrisoned during the War of 1812.[1] Later, it was used for United States governmental functions prior to being abandoned.

History

Background

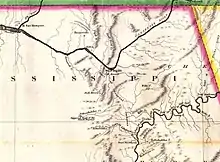

Immediately prior to contact with Europeans, the area that became Alabama was occupied by multiple groups of Native Americans, including the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw. As American settlement expanded west, Native American tribal territory and alliances evolved due to increased contact with the new settlers. Prior to being controlled by the newly formed United States, the current area of Limestone County was claimed at times by the Chickasaw, Cherokee, or the British. After defeating the Shawnee (who had previously occupied the territory in the early 1700s), the Chickasaw gained control of the Tennessee Valley in northwest Alabama.[3] In 1806, the Cherokee sold their claim on Limestone County, north of the Tennessee River, but the Chickasaw retained their rights to the land, causing a boundary to be created to separate Chickasaw land from land available for purchase and settlement.[4]

The first Anglo settlers in North Alabama are believed to have arrived via flatboats on the Tennessee River from East Tennessee. Other settlers came from Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, and followed established Native American trading paths. Many of these early settlers were drawn to the area by the easy access to navigable waterways and fertile soil that afforded ample areas for growing cotton.[5] Some of these settlers ignored previously established boundary lines and settled on land claimed by the Chickasaw. The Chickasaw (through the family of George Colbert) petitioned the United States to stop illegal settling of their land, and in response, the United States ordered these settlers to leave the area. In 1809, Colonel Return J. Meigs Sr. and a company of thirty soldiers marched from Kingston, Tennessee, and forced settlers to move out of Chickasaw territory.[6] Even so, many settlers did not leave or soon returned, and Meigs suggested a permanent military presence would be required to prevent them from returning again. This resulted in the construction of Fort Hampton by the United States Army in the fall of 1810.[7]

Construction

In 1810, Brigadier General Wade Hampton ordered Major John Fuller and one hundred and four men (two companies) of the Regiment of Riflemen to march from Cantonment Washington to the Elk River region of North Alabama. After a forty-eight day march in the middle of the summer, the soldiers arrived at the site of Fort Hampton without any tools, tents or other supplies, their barge of supplies delayed.[2]

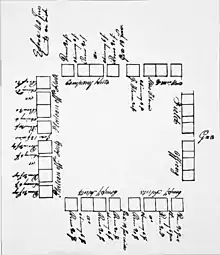

Fort Hampton was built on a hill southeast of the Elk River in what is now Limestone County, Alabama. This location was chosen due to its close proximity to the intruding settlements and to Melton's Bluff, a nearby community where it was originally intended to be built. [8] Initially, the fort only consisted of a collection of log cabins, a brickyard and stables and had no fortifications or armory.[2][9] The fort also had no prominent forms of defense due to its designed nature as a diplomatic establishment.[10] Eventually, a central courtyard surrounded by thirty-two log cabins was constructed.[11] In 1812, it was made defensive, enclosed, blockaded and cannons were placed outside.[8]

Military use

After construction, Fort Hampton was used as a base from which soldiers performed various duties, mostly road building, but also patrols and protection of Chickasaw property.[12] The primary role of the troops was to keep settlers off Chickasaw lands, and as part of this process they burned the cabins of numerous early inhabitants of Limestone and Lauderdale counties.[13]

Fort Hampton was initially garrisoned by a company of soldiers from the newly organized Regiment of Riflemen under Major John Fuller, but he was soon arrested and relieved of duty and Colonel Robert Purdy of the 7th United States Infantry assumed command.[2] The Regiment at the fort consisted of one hundred riflemen, Colonel Smyth, who assumed command when Purdy returned to his post, Captains George W. Sevier (son of John Sevier) and James McDonald, and Major Fuller until early 1811.[8] Colonel John Williams of the 39th Infantry Regiment was also stationed at Fort Hampton for a time.[14]

Sam Houston was stationed at Fort Hampton after joining the United States Army in 1813.[15] His brother Robert was the commanding officer of the 8th Infantry at the fort from 1816 until the fort was abandoned in 1817.[16]

In a letter to Major General John Alexander Cocke in October 1813, Andrew Jackson warned of a possible impending Creek attack on Fort Hampton and Huntsville. In response, Jackson ordered General John Coffee to reinforce the militia at Huntsville and Captain McClellan and his troops at Fort Hampton.[17] The attack never occurred, and after temporarily staying at Fort Hampton, Coffee proceeded to the Black Warrior River valley to scout out hostile Creeks and burn any villages his troops found.[18]

When Jackson began offensives against Pensacola and New Orleans, David Holmes, governor of Mississippi Territory, ordered soldiers and supplies from Fort Hampton to be sent to Jackson's forces.[19] When these forces left, militia Captain John Allen's men occupied Fort Hampton for almost an entire year. In addition to his military service, Allen served as a subagent for the Chickasaw.[20] Allen's men performed their duty without initially being paid, but were compensated within two years of their service.[21]

The 1st Regiment of West Tennessee Volunteer Mounted Gunmen were briefly stationed at Fort Hampton en route to New Orleans in the winter of 1814.[22]

In August 1816, the 8th Infantry Regiment of the United States was stationed at Fort Hampton under the direction of Robert Butler, Andrew Jackson’s Adjutant General of the 7th Military District of the South.[23]

Postwar

After the Chickasaw sold the territory surrounding Fort Hampton to the United States, the presence of U.S. troops was no longer needed and the military post at the fort was disbanded. Troops were sent to begin construction of the northern portion of the Jackson military road.[23]

Some of the buildings of Fort Hampton were still standing in 1821, but most were believed to have been moved from the original site.[24] Fort Hampton was then used as a court site for Elk County, Mississippi Territory and Limestone County, Alabama Territory.[25]

A community of the same name developed around Fort Hampton and a post office operated under that name from 1861 to 1872.[26] The Improved Order of Red Men and Independent Order of Good Templars both had lodges in Fort Hampton.[27][28]

Present

The original site of Fort Hampton is now occupied by a private residence. A historical marker was placed by the Limestone County Historical Society on the shoulder of U.S. Route 72 in the 1970s.[29]

The site was excavated by a team from the University of West Florida in 2013. The fort site was positively identified and some artifacts related to the fort's military use were recovered.[30]

References

- 1 2 Harris 1977, pp. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Cole & Hoksbergen 2020, pp. 3.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 20.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 22.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 24.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 25.

- 1 2 3 Cole & Hoksbergen 2020, pp. 5.

- ↑ Roberts 2020, pp. 103.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 98.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 30.

- ↑ Cole & Hoksbergen 2020, pp. 6.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Roberts 2020, pp. 115.

- ↑ Lester 1883, pp. 21.

- ↑ Cole & Hoksbergen 2020, pp. 7.

- ↑ Jackson 1926, pp. 332.

- ↑ Weir 2016, pp. 210.

- ↑ Holmes 1927, pp. 44.

- ↑ "Signers – Allen, John L." Indian Land Tenure Foundation Initiative Treaty Signers Project. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ↑ Roberts 2020, pp. 117.

- ↑ Kanon, Tom. "Regimental Histories of Tennessee Units During the War of 1812". Tennessee State Library and Archives. State of Tennessee. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- 1 2 Cole & Hoksbergen 2020, pp. 8.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 41.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 33.

- ↑ "Limestone County". Jim Forte Postal History. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Lindsay, Conley & Litchman 1893, pp. 439.

- ↑ Spencer 1870, pp. 10.

- ↑ "The Big Dig: Limestone Native to Discuss the Real Fort Hampton". The News Courier. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ↑ Chandler 2014, pp. 45.

Sources

- Chandler, Tonya Johnson (2014). An Archaeological and Historical Study of Fort Hampton, Limestone County, Alabama (1809–1816) (PDF) (MA). University of West Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Cole, Mark; Hoksbergen, Ben (2020). "Fort Hampton the Riflemen and the Mississippi Territory Frontier 1808-1817".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Harris, W. Stuart (1977). Dead Towns of Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1125-4.

- Holmes, David (1927) [Composed 7 September 1814]. Bassett, John Spencer (ed.). Correspondence of Andrew Jackson. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Jackson, Andrew (1926) [Composed 10 October 1813]. Bassett, John Spencer (ed.). Correspondence of Andrew Jackson. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Lester, Charles Edwards (1883). Life and Achievements of Sam Houston: Hero and Statesman. New York, New York: Hurst.

- Lindsay, George W.; Conley, Charles C.; Litchman, Charles H. (1893). Official History of the Improved Order of Red Men. Boston, Massachusetts: Fraternity Publishing Company.

- Roberts, Frances Cabaniss (2020). The Founding of Alabama: Background and Formative Period in the Great Bend and Madison County. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-2043-0.

- Spencer, J. A. (1870). Journal of Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Session of the Right Worthy Grand Lodge of North America. Cleveland, Ohio: Grand Lodge.

- Weir, Howard (2016). A Paradise of Blood: The Creek War of 1813–14. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-270-1.