Fort Washita | |

West barracks in 1975 | |

| |

| Location | Bryan County, Oklahoma |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Durant, Oklahoma |

| Coordinates | 34°6′13″N 96°32′54″W / 34.10361°N 96.54833°W |

| Built | 1841 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000626[1][2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | June 23, 1965 |

Fort Washita is the former United States military post and National Historic Landmark located in Durant, Oklahoma on SH 199. Established in 1842 by General (later President) Zachary Taylor to protect citizens of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations from the Plains Indians, it was later abandoned by Federal forces at the beginning of the American Civil War. Confederate troops held the post until the end of the war when they burned the remaining structures. It was never reoccupied by the United States military. After years in private hands the Oklahoma Historical Society bought the fort grounds in 1962 and restored the site. In 2017, the Chickasaw Nation purchased Fort Washita from the Oklahoma Historical Society and assumed responsibility for the site and its management. Today, Fort Washita is a tourist attraction and hosts several events throughout the year.[3] In August 2023, the Fort Washita Historic Site was placed into federal trust with the U.S. government. [4]

https://reader.mediawiremobile.com/ChickasawTimes/issues/208621/viewer

Location

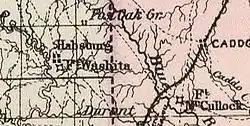

The site is located about 12 miles (19 km) northwest of the present-day town of Durant, Oklahoma, on Oklahoma State Highway 199, just north of the confluence of the Washita River with the Red River. The original fortification was a massive expanse of over seven square miles, containing far more than ninety buildings and sites.[1][5] It was not abandoned until after the end of the war, in 1865.

History

Five Civilized Tribes removed to the Indian Territory

Eager to gain access to the lands of the Five Civilized Tribes in the southern United States the Federal government passed the Indian Removal Act into law on May 26, 1830. The first of the Indians to be removed, the Choctaws, signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, effectively ceding their native lands in Mississippi and Alabama to the United States in exchange for lands in the Indian Territory. After traveling on the Choctaw Trail of Tears the Choctaws settled in the new Choctaw Nation, the southern part of the Indian Territory bordering the Red River.

The Cross Timbers, a thick line of nearly impassable trees and brush running from north to south, created an effective east–west barrier separating the flat, dry lands inhabited by the plains Indians to the west from the rolling prairies to the east where the Five Civilized Tribes were locating. These indigenous tribes included the Comanche, Wichita, Caddoes, and Kiowa. They occasionally threatened the removed tribes with raids. The Choctaws mostly settled in the eastern part of their territory since the western end was less secure against raids from the plains Indians, and they had protection from federal troops located at Fort Towson.

Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition

The first official contact between the United States and the plains Indians was during the Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition in 1834. Camp Washita, the precursor to Fort Washita, was established near the mouth of the Washita River to serve as a base of operations for the area. Two roads were cleared to the area, one from Fort Gibson to the north and one to Fort Towson to the east. Camp Washita was abandoned later that year.

Chickasaw removal

The Chickasaws were removed to the Indian Territory in 1837, paying $530,000 to the Choctaws for the right to live in their lands.[6] After removal to the Indian Territory the Chickasaws were reluctant to settle in their district, composed of the west and central area of the Choctaw lands. The area was not secure against the plains Indians, since the closest federal garrison, at Fort Towson, was too far away to protect the area effectively. In 1838 the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Territory, William Armstrong, asked the War Department to build a military post near the mouth of the Washita River to secure the area so the Chickasaws could move into their assigned territory.[7]

Captain T. A. Blake led a company of Dragoons from Fort Towson to the site of Fort Washita in late 1841.[8]

Location and construction

In response to the need to defend the removed Indians on the frontier the United States Army authorized the construction of a fort on the Choctaw lands west of Fort Towson. General Zachary Taylor, as commander of the Second Military Department in the Southwest,[9] chose the site for Fort Washita in 1842 on high ground a mile and a half east of the Washita River and 18 miles north of its junction with the Red River. At the time the Red River was the southern border of the Indian Territory with new Republic of Texas. The fort was surrounded by rolling prairie.[10] The nearest military post at this time was Fort Towson 80 miles to the east.[9]

Fort Washita sat at a strategic point on the frontier. In addition to being located near the Red and Washita rivers there existed an ancient north–south trail through the area. In the Indian Territory this route was known as the Texas Road, leading from Missouri to Texas and beyond. This route was called the old Preston Trail after it crossed into Texas on the Red River near Preston Bend at Coffee's Trading Post and later Colbert's Ferry. Fort Washita became a major junction on this road. Later the Shawnee Cattle Trail used this north–south route and, just prior to the Civil War, the Butterfield Overland Stage crossed just east of Fort Washita.

Fort Washita was connected to Fort Towson and Fort Gibson by military roads constructed earlier.[11] Later military roads connected Fort Washita with forts Arbuckle and Sill.

The Cross Timbers were located near Fort Washita, about 19 miles west of the Washita River.[12]

Construction at Fort Washita began in the spring of 1842.[9] The Chickasaw Indian Agency was built early on as a one-story log building with four rooms in a group of trees on the edge of the prairie 600 yards west of Fort Washita near the springs.[13] Construction was carried out mostly by Companies A and F of the Second Dragoons, with a temporary log barracks in 1842.[9] There were supply difficulties, since the fort was located so far on the frontier.[9] Most materials had to be taken from the area, with a few supplies being shipped from Fort Towson.

Troops from Fort Washita were ordered to protect Texas frontier from Indian attacks in 1842 so Texans could muster against a supposed invasion from Mexico.[9]

Fort Washita was almost abandoned in 1843 before it was fully occupied. General Taylor learned in March 1843 that the War Department was considering abandoning it. After Taylor testified to the fort's valuable location[9] the War Department approved the plans to occupy the fort, and the United States Army occupied the post on April 23, 1843.

Bean Starr, one of the Starr gang, died at the hospital at Fort Washita after being wounded at a shootout on the Washita River 25 miles above the fort in the Autumn of 1844.[14]

Had corral, stable area, blacksmith, farrier shops.[9]

In 1845 Fort Washita was the only frontier fort not accessible by steamboat and had to rely on the interior for its supply.[15]

The Mexican–American War

When the Mexican–American War began in May 1846 activity increased dramatically at Fort Washita. As a United States military post near Texas the fort served as a staging point for the war. Traffic on the Texas Road heading south increased during and after the war.[16] During the war years the average garrison of 150 troops increased to almost 2000 troops. During this era Fort Washita served as the site of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian Agencies. The Mexican–American War ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848.

The Chickasaws met at Boiling Springs near Fort Washita in 1846 and adopted a constitution. They met again at Boiling Springs on October 13, 1848, and created a more formal constitution, creating their own government separate from the Choctaws.[17] As the Chickasaws moved into their own country near and west of Fort Washita they increasingly needed protection from the fort against the plains Indians.

The temporary log barracks was replaced after the construction of the south barracks from limestone in 1849.

Commanded by Dixon S. Miles in late 1849 and early 1851.[18]

Major Daniel Ruggles served at Fort Washita from 1849 to 1851[19] after the Mexican–American War and eventually commanded the fort. He was popular, and the small settlement west of the fort was named Rugglesville after him.[20] It was sometimes called Rucklesville[10] and later Hatsboro.

Shortly after the Mexican–American War the 2nd Artillery Regiment, commanded by Colonel Braxton Bragg and made famous at the Battle of Buena Vista, was assigned to the fort.[21] Bragg was later a General in the Confederate Army.[9]

Moving frontier and the Gold Rush

Beginning after the discovery of gold in California in 1848 many settlers bound for California traveled through Fort Washita headed west.[22] Many emigrants to California chose a more southern route to avoid the cold winters, the snow, and cholera outbreaks that plagued the northern routes. The major obstacle to using the southern route was the indigenous plains Indians that lived along this route. Travelers gathered in large groups for protection while crossing to California. "It was customary for the emigrating parties to rendezvous at Fort Washita, where detachments would consolidate, elect their officers and make their final preparations before crossing Red River into Texas and straightening out on their long southwestern tangent to El Paso."[23] In 1850 General Arbuckle, commander at Fort Smith, ordered the establishment of a fort west of Fort Washita to aid the protection of California emigrants. This fort became Fort Arbuckle.[24]

Fort Worth was established June 6, 1849.[15] The distance between Fort Worth and Fort Washita is 120 miles.[12]

General Belknap, commander of Fort Arbuckle died on November 10, 1851, on an ambulance between Preston, Texas and Fort Washita bound for Fort Gibson to see his family. He was interred at Fort Washita.[25]

The headquarters of the Seventh Military Department was transferred to Fort Washita in 1853. With it Major T. H Holmes commanded the fort.[25] Only one light battery of artillery was assigned to the post in 1853.[26]

The west barracks was built in 1856 from native limestone.[26]

The two artillery batteries at Fort Washita were transferred to Fort Monroe, leaving on December 25, 1856.[27]

By 1858 there was an east barracks, hospital, and surgeon's quarters all built from native stone, in addition to the wooden structures. A corral and stables on the hillside southwest of the fort supported cavalry operations. Cavalry comprised the bulk of the forces assigned to Fort Washita until the 1850s when it served as a United States Army Field Artillery School.[28] Several Artillery units were assigned to the fort during this time in addition to infantry and cavalry.[29] Forts Smith, Washita, Belknap and Arbuckle were abandoned temporarily in 1858 so their troops could be sent to Utah during the Utah War.[30] The Fort closed on February 17, 1858, but was reoccupied later that year on December 29[31] after increased Comanche activity.

Fort Washita's importance as a military post waned as the frontier moved westward. The Chickasaw and Choctaw nations grew more settled and incursions by the plains Indians lessened. As the frontier moved westward new military posts were established farther west to protect the new frontier. The Army established Fort Cobb in October 1859.[32]

Many men who served at Fort Washita would go on to become famous, including Randolph B. Marcy, George McClellan, William G. Belknap[9] and Theophilus H. Holmes.

The Civil War and abandonment

Federal troops still occupied Fort Washita when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Expecting war, Colonel William Emory had concentrated all of his Federal troops from Forts Arbuckle and Cobb at Fort Washita.[33] When news of Fort Sumter reached Emory on April 16 he led his forces to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, pursued by 4000 Texas militia one day behind them.[34] Afterwards the Confederate forces seized Fort Washita. Both the Choctaw and Chickasaw were allied with the Confederacy throughout the duration of the war. During the Civil War Fort Washita saw no action, though it was an important supply depot for the Confederates in the Indian Territory.[9] It also served as military hospital.[9] Fort Washita became the headquarters of Brigadier General Douglas Cooper, who assumed command after the battle of Honey Springs.[9] Other Confederate commanders during the Civil War include General Albert Pike, served as commander of Fort Washita for a short time before establishing Fort McCulloch a few miles to the east, and General Stand Watie. Near the end of the war, Confederate forces burned the existing buildings and abandoned the post. A confederate cemetery remains to this day on the fort grounds. United States military graves were exhumed and reinterred at Fort Gibson near Muskogee, Oklahoma.

After the Civil War Fort Washita was never reoccupied by the United States military and the grounds fell into disuse. On July 1, 1870, the War Department handed over the fort grounds to the Department of the Interior. The passage of the Dawes Act in 1887 and the Atoka Agreement in 1897 divided the communal lands of the Chickasaw Nation, including Fort Washita, into allotments owned by individual Chickasaw citizens. The Colberts, a prominent Chickasaw family, received the allotment of grounds including the fort. Department of Interior turned land over to Abbie Davis Colbert and her son.[9] Charles Colbert turned the existing east barracks into a personal home and the site was used as a farm for many years. The remaining buildings were used in a farming capacity. The Colberts also used the cemetery as a family cemetery. The old west barracks continued to serve as the Colberts' household until it burned down in 1917.[26]

Douglas H. Cooper, once commander of Fort Washita and later commander of Confederate Troops in Indian Territory, continued to live at the fort after the Civil War. He died there on April 29, 1879, and was buried in the old fort cemetery in an unmarked grave.[35]

National Historic Landmark

In 1927, Dr. William Brown Morrison, a history professor at Southeastern Oklahoma State University (then Southeastern State Normal School) visited the ruins of the fort and reported that "while rapidly disintegrating and disappearing, these ruins are still very extensive and very interesting to those who may be inclined to study the history of Oklahoma in the days long gone by."[22]

In the 1960s there was a renewed interest in Oklahoma's Historical Sites. The Oklahoma Historical Society was able to determine that at the Fort Washita site there were 86 structures, 50 foundations and 2 structures still standing.[36]

Ward S. Merrick Sr. of Ardmore, Oklahoma contributed funds to the Oklahoma Historical Society for the purchase of the site from the Colbert family in 1962. At the time, William "Buck" Loper and his wife, Lela, lived in the current park headquarters. During the sale of the property to the Historical Society, the Colberts allowed the Lopers to stay until their death around 1963. They are both buried in the fort cemetery. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965[1][5] and in 1967 the Oklahoma State Legislature approved $10,000 for the reconstruction and restoration of the fort's grounds. In 1971 the Oklahoma Historical Society conducted an archeological dig and rebuilt the south barracks.

Today the Fort Washita site is home to Fort Washita Historic Site and Museum, Civil War reenactments, and a yearly Fur Trade Rendezvous.[37]

On September 26, 2010, the reconstructed South Barracks was destroyed by fire.[38]

Commanders

- James Dean, Captain, 3rd Infantry May 1834-

- George A. H. Blake, Captain, April 1842-

- Thomas Faunteroy, Major 2nd class, October 1844-

- Benjamin L Beall Captain assumed command December 1842.

- W.J. Newton, Jan 1842

- Benjamin L. Beall, Capt. Feb 1842

- Benjamin L. Beall, Brev Maj, April 1843

- W.S. Harney, Brev Colo., June 1843

- B.L. Beall, Brev Major, Jan 1844-May 1844, Mar-May 1845

- W.S. Harney, Brev Colonel (2nd Dragoons) June 1844

- Theophilus Hunter Holmes May 1851 to December 1855.[39]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Oklahoma Historical Society State Historic Preservation Office".

- ↑ "Fort Washita". Chickasaw.net. The Chickasaw Nation. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ↑ "Fort Washita". Chickasaw.net. The Chickasaw Nation. 17 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- 1 2 Joseph Scott Mendinghall (September 2, 1976). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Fort Washita (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying 9 photos, exterior and interior, from 1957 and 1975. (2.46 MB)

- ↑ "Chickasaw.tv | Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw, 1837 (also known as Treaty of Doaksville)". www.chickasaw.tv. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Gibson 1971, p. 221

- ↑ Gibson 1971, p. 222

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Rodriguez 2002, p. 349

- 1 2 Glisan 1874, p. 46

- ↑ Foreman 1925, p. 102

- 1 2 Johnston, Joseph; Randolph Marcy; William Whiting (1850). Reports of the Secretary of War: With Reconnaissances of Routes from San Antonio to El Paso. Union Office. pp. 250.

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 127

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 343

- 1 2 United States Congress (1852). Senate Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Public Documents and Executive Documents: 14th Congress, 1st Session-48th Congress, 2nd Session and Special Session. Washington, D.C. pp. 220–221.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Foreman 1925, p. 117

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 120

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 134

- ↑ Cullum 1891, p. 563

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 140

- ↑ Morrison, W. B. "A Visit to Old Fort Washita" Archived 2015-07-31 at the Wayback Machine, Chronicles of Oklahoma 7:2 (June 1929) 176

- 1 2 Morrison 1927, p. 176

- ↑ Foreman 1925, p. 112

- ↑ Foreman 1989, p. 137

- 1 2 Foreman 1989, p. 139

- 1 2 3 Sprague 2007, p. 16

- ↑ Reilly 1909, p. 495

- ↑ The Civil War Preservation Trust. "Civil War Discovery Trail"

- ↑ Oklahoma Historical Society. "Oklahoma Historical Society - Military Sites"

- ↑ Daily Southern Cross. May 4, 1858

- ↑ Morrison, W. B. "Fort Washita" Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, Chronicles of Oklahoma 2:2 (June 1927) 256

- ↑ Petersen 2007, p. 26

- ↑ Ball, p. 192

- ↑ Ball, p. 194

- ↑ "This Week in the Civil War: Douglas Hancock Cooper biography." Civil War Week. August 28, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ↑ Blackburn, Bob L. "Battle Cry for History". Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed January 7, 2022.

- ↑ Nichols, Max. "Rendezvous to show life on frontier", NewsOK, February 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Fort Washita landmark burns to the ground", KXII-TV, September 26, 2010.

- ↑ National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916; Microfilm Serial: M617; Microfilm Roll: 1387.

References

- Ball, Durwood (2001). Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-8061-3312-6.

- Cullum, George Washington (1891). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.: Nos. 1-1000. Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Foreman, Grant (June 1925). "Early Trails Through Oklahoma". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 3 (2). Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- Foreman, Grant (1989). The Five Civilized Tribes. Norman, Oklahoma, United States of America: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0923-8.

- Gibson, Arrell (1971). The Chickasaws. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1042-4.

- Glisan, Rodney (1874). Journal of Army Life. A. L. Bancroft.

- Morrison, W.B. Fort Washita. Oklahoma Historical Society (1927).

- Petersen, Paul (2007). Quantrill in Texas: The Forgotten Campaign. Cumberland House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58182-582-4.

- Reilly, James (1909). "An Artilleryman's Story". Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. 45.

- Rodriguez, Junius (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-188-X.

- Sprague, Donovin (2007). Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-4147-1.

- "THE MORMON WAR". Daily Southern Cross. May 4, 1858.

Further reading

- Adams, George R. William S. Harney U of Nebraska Press (2001) 389.

- Corbett, William P. "Rifles and Ruts: Army Road Builders in the Indian Territory," Chronicles of Oklahoma 60:294-309 (1982)

- Dyer, Brainerd. Zachary Taylor. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press (1946)

- Fowler, Jack D. "Amid Bedbugs and Drunken Seccessionists." Civil War Times Illustrated 36:44-50 (1997)

- Frazer, Robert W. Forts of the West: Military Forts and Presidios, and Posts Commonly Called Forts, West of the Mississippi River to 1898 (2d ed.; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972).

- Hart, Herbert (1964). Old forts of the Southwest. Superior Pub. Co. ISBN 9780875643151.

- Holcomb, Raymond L. The Civil War in the Western Choctaw Nation, 1861-1865. Atoka, OK: Atoka County Historical Society (1990)

- Howard, James A. II, "Fort Washita," in Early Military Forts and Posts in Oklahoma, ed. Odie B. Faulk, Kenny A. Franks, and Paul F. Lambert (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1978).

- Lewis, Kenneth E. "Fort Washita From Past to Present An Archeological Report" (1975)

- Methvin, J.J. "The Fly Leaf", Chronicles of Oklahoma 6:3 (September 1928) 14-35

- Parker, William B. Notes Taken During the Expedition Commanded by Capt. R. B. Marcy, U. S. A., Through Unexplored Texas, in the Summer and Fall of 1854 Hayes & Zell (1856) 242.

- Perrine, Fred S. "The Journal of Hugh Evans Archived 2006-09-02 at the Wayback Machine," Chronicles of Oklahoma 3:3 (September 1925) 2-215 (retrieved November 17, 2008).

- Shirk, George H. "Mail Call at Fort Washita", Chronicles of Oklahoma 33:1 (1955) 14-35

- Shirk, George H. "Peace on the Plains," Chronicles of Oklahoma 28:1 (January 1950) 2-41 (retrieved November 17, 2008).

- Official Army Register for 1851

External links

- Fort Washita - Official site at the Oklahoma Historical Society

- Fort Washita Tour Map and Guide

- Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Fort Washita

- Fort Washita Information & Video - Chickasaw.TV

- Fort Washita - history, restoration and ghosts

- Fort Washita pamphlet

- National Park Service - Soldier and Brave (Fort Washita)

- Fort Washita info, photos and video on TravelOK.com Official travel and tourism website for the State of Oklahoma

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory