| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

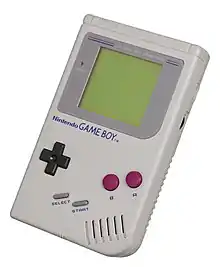

In the history of video games, the fourth generation of video game consoles, more commonly referred to as the 16-bit era, began on October 30, 1987, with the Japanese release of NEC Home Electronics' PC Engine (known as the TurboGrafx-16 in North America). Though NEC released the first console of this era, sales were mostly dominated by the rivalry between Sega and Nintendo across most markets: the Sega Mega Drive (Sega Genesis in North America) and the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES; Super Famicom in Japan). Cartridge-based handheld consoles became prominent during this time, such as the Nintendo Game Boy (1989), Atari Lynx (1989), Sega Game Gear (1990) and TurboExpress (1990).

Nintendo was able to capitalize on its success in the previous, third generation, and managed to win the largest worldwide market share in the fourth generation as well. Sega, however, was extremely successful in this generation and began a new franchise, Sonic the Hedgehog, to compete with Nintendo's Super Mario series of games. Several other companies released consoles in this generation, but none of them were widely successful. Nevertheless, there were other companies that started to take notice of the maturing video game industry and begin making plans to release consoles of their own in the future. While as with prior generations, game media still continued to be primarily provided on ROM cartridges, though the first optical disk systems, such as the Philips CD-i, were released to limited success. As games became more complex, concerns over video game violence, namely in titles such as Mortal Kombat and Night Trap, led to the eventual creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Board.

The emergence of fifth generation video game consoles, circa 1994, did not significantly diminish the popularity of fourth generation consoles for a few years. In 1996, however, there was a major drop in sales of hardware from this generation and a dwindling number of software publishers supporting fourth generation systems,[1] which together led to a drop in software sales in subsequent years. This generation ended with the discontinuation of the Neo Geo in 2004.

Differences from third generation consoles

Features that distinguish some fourth generation consoles from third generation consoles include:

- 16-bit microprocessors

- Multi-button game controllers with many buttons (3 to 8)

- Parallax scrolling of multi-layer tilemap backgrounds

- Large sprites (up to 64×64 or 16×512 pixels), 80–380 sprites on screen, 16–96 sprites per scan line

- Elaborate color, 64 to 4096 colors on screen, from palettes of 512 (9-bit) to 65,536 (16-bit) colors

- Stereo audio, with multiple channels and digital audio playback (PCM, ADPCM, streaming CD-DA audio)

- Advanced music synthesis (FM synthesis and/or wavetable sample-based synthesis)

Additionally, in specific cases, fourth generation hardware featured:

- Backgrounds with pseudo-3D scaling and rotation

- Sprites that can individually be scaled and rotated

- Flat-shaded 3D polygon graphics

- Surround sound support

- CD-ROM support via add-ons, allowing larger storage space and full motion video playback

Home systems

TurboGrafx-16

The PC Engine was the result of a collaboration between Hudson Soft and NEC and launched in Japan on October 30, 1987. It launched under the name TurboGrafx-16 in North America on August 29, 1988.

Initially, the PC Engine was quite successful in Japan, partly due to titles available on the then-new CD-ROM format. NEC released a CD add-on in 1990 and by 1992 had released a combination TurboGrafx and CD-ROM system known as the TurboDuo.

In the United States, NEC used Bonk, a head-banging caveman, as their mascot and featured him in most of the TurboGrafx advertising from 1990 to 1994. The platform was well received initially, especially in larger markets, but failed to make inroads into the smaller metropolitan areas where NEC did not have as many store representatives or as focused in-store promotion.

The TurboGrafx-16 failed to maintain its sales momentum or to make a strong impact in North America.[2] The TurboGrafx-16 and its CD combination system, the Turbo Duo, ceased manufacturing in North America by 1994, though a small amount of software continued to trickle out for the platform.

Mega Drive/Genesis

The Mega Drive was released in Japan on October 29, 1988.[3] The console was released in New York City and Los Angeles on August 14, 1989, under the name Sega Genesis, and in the rest of North America later that year.[4] It was launched in Europe and Australia on November 30, 1990, under its original name.

Sega built their marketing campaign around their new mascot Sonic the Hedgehog,[5] pushing the Genesis as the "cooler" alternative to Nintendo's console[6] and inventing the term "Blast Processing" to suggest that the Genesis was capable of handling games with faster motion than the SNES.[7] Their advertising was often directly adversarial, leading to commercials such as "Genesis does what Nintendon't" and no scream at all.[8]

When the arcade game Mortal Kombat was ported for home release on the Genesis and Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Nintendo decided to censor the game's gore, but Sega kept the content in the game, via a code entered at the start screen. Sega's version of Mortal Kombat received generally more favorable reviews in the gaming press and outsold the SNES version three to one. This also led to Congressional hearings to investigate the marketing of violent video games to children, and to the creation of the Interactive Digital Software Association and the Entertainment Software Rating Board.[9] Sega concluded that the superior sales of their version of Mortal Kombat were outweighed by the resulting loss in consumer trust, and cancelled the game's release in Spain to avoid further controversy.[10] With the new ESRB rating system in place, Nintendo reconsidered its position for the release of Mortal Kombat II, and this time became the preferred version among reviewers.[11][12] The Toy Retail Sales Tracking Service reported that during the key shopping month of November 1994, 63% of all 16-bit video game consoles sold were Sega systems.[13]

The console was never popular in Japan (being regularly outsold by the PC Engine), but still managed to sell 40 million units worldwide. By late 1995, Sega was supporting five different consoles and two add-ons, and Sega Enterprises chose to discontinue the Mega Drive in Japan to concentrate on the new Sega Saturn.[14] While this made perfect sense for the Japanese market, it was disastrous in North America: the market for Genesis games was much larger than for the Saturn, but Sega was left without the inventory or software to meet demand.[15]

Super NES

Nintendo executives were initially reluctant to design a new system, but as the market transitioned to the newer hardware, Nintendo saw the erosion of the commanding market share it had built up with the Nintendo Entertainment System.[16] Nintendo's fourth-generation console, the Super Famicom, was released in Japan on November 21, 1990; Nintendo's initial shipment of 300,000 units sold out within hours.[17] The machine reached North America as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System on August 23, 1991,[cn 1] and Europe and Australia in April 1992.

Despite stiff competition from the Mega Drive/Genesis console, the Super NES eventually took the top selling position, selling 49.10 million units worldwide,[24] and would remain popular well into the fifth generation of consoles.[25] Nintendo's market position was defined by their machine's increased video and sound capabilities,[26] including exclusive first-party franchise titles such as F-Zero, Super Mario World, Star Fox, Super Mario Kart, Donkey Kong Country, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Super Metroid.

Compact Disc Interactive (CD-i)

The CD-i format was announced in the late 1980s, with the first machines compatible with the format being released in 1991. The Philips CD-i's main selling point was that it was more than a game machine and could be used for multimedia needs. Due to an agreement between Nintendo and Philips about an abortive CD add-on for the SNES (which eventually evolved into Sony's PlayStation), Philips also had rights to use some of Nintendo's franchises. The CD-i was a commercial failure and was discontinued in 1998,[27] selling only 1 million units worldwide despite several partnerships and multiple versions of the device, some made by other manufacturers.

Neo Geo

Released by SNK in 1990, the Neo Geo was a home console version of the major arcade platform. Compared to its console competition, the Neo Geo had much better graphics and sound, however the prohibitively expensive launch price of US$649.99 and games often retailing at over $250 made the console only accessible to a niche market. A less expensive version, retailing for $399.99, did not include a memory card, pack-in game or extra joystick.

Add-ons

Nintendo, NEC and Sega also competed with hardware peripherals for their consoles in this generation. NEC was the first with the release of the TurboGrafx CD system in 1990. Retailing for $399.99 at release, the CD add-on was not a popular purchase, but was largely responsible for the platform's success in Japan.[28] The Sega CD was released with an unusually high price tag ($300 at its release) and a limited library of games. A unique add-on for the Sega console was Sega Channel, a subscription-based service (a form of online gaming delivery) hosted by local television providers. It required hardware that plugged into a cable line and the Genesis.

Nintendo also made two attempts with the Satellaview and the Super Game Boy. The Satellaview was a satellite service released only in Japan and the Super Game Boy was an adapter for the SNES that allowed Game Boy games to be displayed on a TV in color. Nintendo, working along with Sony, also had plans to create a CD-ROM drive for the SNES (plans that resulted in a prototype version of the Sony PlayStation), but eventually decided not to go through with that project, opting to team up with Philips in the development of the add-on instead (contrary to popular belief, the CD-i was largely unrelated to the project).

.jpg.webp) PC Engine CoreGrafx II with Super CD-ROM2

PC Engine CoreGrafx II with Super CD-ROM2

European importing

The fourth generation was also the era when the act of buying imported US games became more established in Europe, and regular stores began to carry them. The PAL region has a refresh rate of 50 Hz (compared with 60 Hz for NTSC) and a vertical resolution of 625 interlaced lines (576 effective), compared with 525/480 for NTSC. Because the simulation speed of contemporary game systems was directly linked to the output frame rate, which was in turn synchronized with the TV's refresh rate, this meant that the game would run more slowly on a PAL television. The smaller number of vertical lines in the NTSC signal would also lead to black bars appearing on the top and bottom of a PAL television. Developers often had a hard time converting games designed for the American and Japanese NTSC standard to the European and Australian PAL standard. Companies such as Konami, with large budgets and a healthy following in Europe and Australia, readily optimized several games (such as the International Superstar Soccer series) for this audience, while most smaller developers did not.

Also, few RPGs were released in Europe because the market for the genre was not as large as in Japan or North America, and the increasing amount of time and money required for translation as RPGs became more text-heavy, in addition to the usual need to convert the games to the PAL standard, often made localizing the games to Europe a high-cost venture with little potential payoff.[29][30] As a result, RPG releases in Europe were largely limited to games which had previously been localized for North America, thus reducing the amount of translation required.[30]

Popular US games imported at this time included Final Fantasy IV (known in the US as Final Fantasy II), Final Fantasy VI (known in the US as Final Fantasy III), Secret of Mana, Street Fighter II, Chrono Trigger, and Super Mario RPG. Secret of Mana and Street Fighter II would eventually receive official release in Europe, whilst Final Fantasy IV, Final Fantasy VI, Chrono Trigger and Super Mario RPG would be released in Europe years later on other consoles or formats outside of this generation.

Comparison

| Name | PC-Engine/TurboGrafx-16 | Mega Drive/Genesis | Super Famicom/Super Nintendo | Neo Geo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | NEC | Sega | Nintendo | SNK |

| Image(s) |    |

|

|

|

| Launch prices (USD) | US$199.99 (equivalent to $472 in 2022) | US$189.99 (equivalent to $449 in 2022) | US$199.99 (equivalent to $430 in 2022) | US$649.99 (Gold version) (equivalent to $1,397 in 2022)

US$399.99 (Silver version) (equivalent to $859 in 2022) |

| Release date | ||||

| Media |

|

| ||

| Best-selling games | Bonk's Adventure[32] | Sonic the Hedgehog (15 million)[33] | Super Mario World, 20 million (as of June 25, 2007)[34] | Samurai Shodown |

| Backward compatibility | N/A | Master System (using Power Base Converter) | Nintendo Entertainment System (unlicensed, using Super 8)

Game Boy (using Super Game Boy) |

N/A |

| Accessories (retail) |

|

|

|

|

| CPU |

|

32X Add-on:

|

|

|

| GPU |

|

Upgrades: |

|

|

| Sound chip(s) |

32X Add-on: |

Sony APU (Audio Processing Unit)

|

Yamaha YM2610 | |

| RAM |

Upgrades:

|

Upgrades: |

Enhancement chips: |

|

| Video |

Upgrades:

|

Upgrades:

|

Enhancement chips:

|

|

| Audio | Stereo audio with:

Upgrades:

|

Stereo audio with:

|

Stereo audio with: |

CD-supported consoles

| Name | CD-ROM²/TurboGrafx-CD | CD-i | Sega CD/Mega-CD | PC Engine Duo/TurboDuo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | NEC | Philips | Sega | NEC |

| Console |  .jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

| Launch prices (USD) | US$399.99 (equivalent to $896 in 2022) | US$799 (equivalent to $1,717 in 2022) | US$299 (equivalent to $642 in 2022) | US$299.99 (equivalent to $626 in 2022) |

| Release date | ||||

| Accessories (retail) |

|

|

|

|

| CPU |

Hudson Soft HuC6280A (based on 8-bit 65SC02) |

Philips SCC68070 @ 15.5 MHz |

Motorola 68000 @ 12.5 MHz (2.19 MIPS)[36] |

Hudson Soft HuC6280A (based on 8-bit 65SC02) |

| GPU |

|

Philips SCC66470, MCD 212 |

Sega ASIC coprocessor[62] |

|

| Sound chip(s) |

MCD 221, ADPCM eight channel sound |

|||

| RAM |

Super CD-ROM²:

Upgrades: |

1 MB RAM |

CD BackUp Ram Carts:

|

|

| Audio |

|

Stereo audio with:

|

Stereo audio with:

|

Other consoles

Commodore CDTV

Commodore CDTV

Released in 1991 Wondermega, Victor RG-M1 Model

Wondermega, Victor RG-M1 Model

Sega Genesis and CD combo released in 1992.

Redesigned for a North American release as X'Eye in September 1994. Wondermega, Victor RG-M2 Model

Wondermega, Victor RG-M2 Model

Released in Japan on 1993 Sega Pico

Sega Pico

Released in 1993

Super A'Can

Super A'Can

Released in Taiwan on October 25, 1995

Worldwide sales standings

| Console | Firm | Units sold |

|---|---|---|

| Super Nintendo Entertainment System | Nintendo | 49.1 million[76] |

| Sega Mega Drive/Genesis | Sega | 35.25 million[cn 3] |

| PC Engine/TurboGrafx-16 | NEC | 10 million[82] |

| Sega CD | Sega | 2.765 million[83] |

| PC Engine CD-ROM² | NEC | 1.92 million[84] |

| Neo Geo AES | SNK | 1.18 million[cn 4] |

| Philips CD-i | Philips | 1 million[87] |

| Sega 32X | Sega | 800,000[88] |

| Neo Geo CD | SNK | 570,000[86] |

Handheld systems

The first handheld game console released in the fourth generation was the Game Boy, on April 21, 1989. It went on to dominate handheld sales by an extremely large margin, despite featuring an 8-bit microprocessor and a low-contrast, unlit monochrome screen while all three of its leading competitors had color. Three major franchises made their debut on the Game Boy: Tetris, the Game Boy's killer application; Pokémon; and Kirby. With some design (Game Boy Pocket, Game Boy Light) and hardware (Game Boy Color) changes, it continued in production in some form until 2008, enjoying a better than 18-year run.

The Atari Lynx included hardware-accelerated color graphics, a backlight, and the ability to link up to sixteen units together in an early example of network play when its competitors could only link 2 or 4 consoles (or none at all),[89] but its comparatively short battery life (approximately 4.5 hours on a set of alkaline cells, versus 35 hours for the Game Boy), high price, and weak games library made it one of the worst-selling handheld game systems of all time, with less than 500,000 units sold.[90][91]

The third major handheld of the fourth generation was the Game Gear. It featured graphics capabilities roughly comparable to the Master System (better colours, but lower resolution), a ready made games library by using the "Master-Gear" adaptor to play cartridges from the older console, and the opportunity to be converted into a portable TV using a cheap tuner adaptor, but it also suffered some of the same shortcomings as the Lynx. While it sold more than twenty times as many units as the Lynx, its bulky design – slightly larger than even the original Game Boy; relatively poor battery life – only a little better than the Lynx; and later arrival in the marketplace – competing for sales amongst the remaining buyers who did not already have a Game Boy – hampered its overall popularity despite being more closely competitive to the Nintendo in terms of price and breadth of software library.[92] Sega eventually retired the Game Gear in 1997, a year before Nintendo released the first examples of the Game Boy Color, to focus on the Nomad and non-portable console products.

Other handheld consoles released during the fourth generation included the TurboExpress, a handheld version of the TurboGrafx-16 released by NEC in 1990, and the Game Boy Pocket, an improved model of the Game Boy released about two years before the debut of the Game Boy Color. While the TurboExpress was another early pioneer of color handheld gaming technology and had the added benefit of using the same game cartridges or 'HuCards' as the TurboGrafx16, it had even worse battery life than the Lynx and Game Gear – about three hours on six contemporary AA batteries – selling only 1.5 million units.[91]

List of handheld consoles

| Console | Game Boy / Game Boy Pocket / Game Boy Light | Atari Lynx | Game Gear | PC Engine GT / TurboExpress / PC Engine LT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Nintendo | Atari | Sega | NEC |

| Image |    |

|

|

|

| Launch price | US$189.99 (equivalent to $449 in 2022[95]) | US$299.99 (equivalent to $645 in 2022[95])[97] | ||

| Release date | ||||

| Units sold | 118.69 million,[99] including Game Boy Color units[100] | 500,000[91] | 11 million[91] | 1.5 million[91] |

| Media | Cartridge | Cartridge | Cartridge | Datacard |

| Best-selling games | RoadBlasters | Sonic the Hedgehog 2 | Bonk's Adventure | |

| Backward compatibility | — (Original cartridges compatible with later models) | — | Master System (using Cartridge Adapter) | TurboGrafx-16 (HuCard only) |

| CPU | Sharp LR35902 4.19 MHz |

|

Zilog Z80 3.5 MHz |

HuC6280A (modified 65SC02) 1.79 or 7.16 MHz |

| Memory |

|

64 KB DRAM |

|

|

| Video |

|

|

|

|

| Audio | Stereo audio (using headphones), with:

|

Stereo audio with:

|

Stereo audio (using headphones), with:

|

Stereo audio (using headphones), with:

|

Other handheld game consoles

.jpg.webp)

CD-i Intelligent Discman IVO

CD-i Intelligent Discman IVO

Released in 1991 Watara Supervision

Watara Supervision

Released in 1992 Mega Duck/Cougar Boy

Mega Duck/Cougar Boy

Released in 1993

Software

Milestone titles

- Chrono Trigger (SNES) by Square is frequently listed among the greatest video games of all time.[105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112]

- Dragon Quest V and VI (SFC) by Chunsoft, Heartbeat, and Enix were released on the Japanese Super Famicom, as well as remakes of the first three games originally released for the NES and a dungeon crawler spin-off: Torneko's Great Adventure, which started Chun Soft's popular Fushigi no Dungeon series.

- Donkey Kong Country (SNES) by Rare and Nintendo turned the tide of the console war in favor of Nintendo and became the best-selling game since Super Mario Bros. 3, largely due to its impressive graphics.[113]

- FIFA International Soccer (Genesis, SNES) by Extended Play Productions and EA Sports has been described as one of the most influential sports games ever made.[114]

- Garou: Mark of the Wolves (Arcade, Neo Geo AES) by SNK is considered one of the best fighting games, as well as the "swan song" of the generation. receiving praise for its hand-drawn graphics, and the game's tight and streamlined control scheme.[115]

- Gunstar Heroes (Genesis) by Treasure and Sega is considered one of the best action games of the generation.[116]

- John Madden Football (1990) (Genesis, SNES) by Park Place Productions and EA Sports played an important role in the early success of both the Genesis console and Electronic Arts.[117]

- Super Metroid (SNES) by Nintendo Research & Development 1 and Nintendo is still regarded by many gaming organizations as one of the "best games of all time."[118]

- Mortal Kombat (Arcade, Genesis, SNES) by Midway Games garnered heated controversy over its violent themes, with the uncensored Genesis version outselling the SNES version by nearly three-to-one, ultimately leading to a U.S. Congressional hearing and the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Board.[119]

- NHLPA Hockey '93 (Genesis, SNES) by Park Place Productions and EA Sports is considered one of the most outstanding sports games ever made.[120][121]

- Phantasy Star II (Genesis) by Sega Consumer Development Division 2 and Sega has been cited as one of the best and most influential console RPGs.[122][123][124]

- Secret of Mana (SNES) by Square reintroduced the Seiken Densetsu series, originally conceived as a Final Fantasy spin-off, to Europe and North America.

- Sonic the Hedgehog (Genesis) by Sonic Team and Sega was Sega's bid to compete head-to head with Nintendo's Mario franchise, played a critical role in the success of the Genesis, and received widespread critical acclaim as one of the greatest games ever made, kickstarting a successful franchise.[125]

- Street Fighter II (Arcade, Genesis, SNES, PC Engine) by Capcom was the second game in the series to produce a lasting fanbase and set many of the trends seen in fighting games today, most notably its colorful selection of playable fighters from different countries across the globe.[126] As of 2008, it is Capcom's best-selling consumer game of all time.[127]

- Streets of Rage 2 (Genesis) by Sega AM7 and Sega is considered the best beat 'em up of the generation.[128]

- Super Monaco GP (Arcade, Genesis) by Sega set a new standard for realism in console racing games.[129]

- Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island (SNES) by Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development (Nintendo EAD) and Nintendo is considered perhaps the finest 2D platformer.[130]

- The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (SNES) by Nintendo EAD and Nintendo courted popularity that was larger than that of its predecessors on the NES.[131][132] It was one of the few action-adventures to be released early in the SNES's lifecycle. Zelda II on the NES had been mostly action-based and was side-scrolling, while A Link to the Past drew more inspiration from the original Zelda game with its top-down adventure format.[133][134][135][136]

- Thunder Force IV (Genesis) by Technosoft is considered one of the best shooters on the Genesis, receiving praise for its graphics, including the vertical and parallax scrolling for illustrating the immense environments.

- Ys Book I & II (TurboGrafx) by Nihon Falcom was among the first video games mass released on CD-ROM, when released in Japan in 1989 and in North America in 1990. In addition to receiving praise for its story and gameplay, the game pioneered several technical features, such as voice acting, animated cut scenes, and pre-recorded soundtracks, which would become industry standards later in the decade.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 According to Stephen Kent's The Ultimate History of Video Games, the official launch date was September 9.[18] Newspaper and magazine articles from late 1991 report that the first shipments were in stores in some regions on August 23,[19][20] while it arrived in other regions at a later date.[21] Many modern online sources (circa 2005 and later) report August 13.[22][23]

- ↑ Mega Drive games use the Z80 as a sound controller. The Power Base Converter effectively turns the Mega Drive into a Master System, giving control to the Z80 and leaving the 68000 dormant.

- ↑ 30.75 million sold by Sega worldwide as of June 1996.[77][78] 1.5 million projected by Majesco Entertainment of the Genesis 3 in 1998.[79] 3 million sold by Tectoy in Brazil as of 2012.[80][81]

- ↑ 1 million in Japan.[85] 180,000 overseas.[86]

References

- ↑ "16-Bit's Final Hurrah". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 88. Ziff Davis. November 1996. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Sartori, Paul (April 2, 2013). "TurboGrafx-16: the console that time forgot (and why it's worth re-discovering)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2017 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ↑ Console Database Staff. "Sega Mega Drive Console Information". Console Database. Console Database/Dale Hansen. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 404–405. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 424–431. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 434, 448–449. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ "The Essential 50 Part 28: Sonic the Hedgehog". www.1up.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 405. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (July 29, 2009). "July 29, 1994: Videogame Makers Propose Ratings Board to Congress". Wired. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "International Outlook". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 53. Sendai Publishing. December 1993. p. 90.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 461–480. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Ray Barnholt (August 4, 2006). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the Super NES". 1UP.com. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Semrad, Ed (March 1994). "Sega Sets the Pace for 1994!". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 56. Sendai Publishing. p. 6.

- ↑ "History of the Sega Mega Drive - Sega Retro". segaretro.org. June 18, 2021. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 508, 531. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 413–414. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ "Why Super Nintendo Is the Reason You're Still Playing Video Games". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ Kent (2001), p. 434. Kent states September 1 was planned but later rescheduled to September 9.

- ↑ Campbell, Ron (August 27, 1991). "Super Nintendo sells quickly at OC outlets". The Orange County Register.

Last weekend, months after video-game addicts started calling, Dave Adams finally was able to sell them what they craved: Super Nintendo. Adams, manager of Babbages in South Coast Plaza, got 32 of the $199.95 systems Friday.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - ↑ "Super Nintendo It's Here!!!". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 28. Sendai Publishing Group. November 1991. p. 162.

The Long awaited Super NES is finally available to the U.S. gaming public. The first few pieces of this unit hit the store shelves on August 23, 1991. Nintendo, however, released the first production run without any heavy fanfare or spectacular announcements.

- ↑ "New products put more zip into the video-game market". Chicago Sun-Times. August 27, 1991. Archived from the original (abstract) on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

On Friday, area Toys R Us stores [...] were expecting Super NES, with a suggested retail price of $199.95, any day, said Brad Grafton, assistant inventory control manager for Toys R Us.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - ↑ Ray Barnholt (August 4, 2006). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the Super NES". 1UP.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Super Nintendo Entertainment System". N-Sider.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. January 27, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Allen, Danny (December 22, 2006). "A Brief History of Game Consoles, as Seen in Old TV Ads". PC World. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- ↑ Jeremy Parish (September 6, 2005). "PS1 10th Anniversary retrospective". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- ↑ Blake Snow (July 30, 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 8, 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ↑ Nutt, Christian (September 12, 2014). "Stalled engine: The TurboGrafx-16 turns 25". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Nintendo Ultra 64: The Launch of the Decade?". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 2. November 1995. pp. 107–8.

- 1 2 "Preview: Shining the Holy Ark". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 19. May 1997. p. 33.

- ↑ Santulli, Joe (2005). Digital Press Collectors Guide. USA: Digital Press. ISBN 978-0-9709807-0-0.

- ↑ "Bonk's Adventure Virtual Console Review - Wii Review at IGN". Wii.ign.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ Sonic the Hedgehog GameTap Retrospective Pt. 3/4. Event occurs at 1:21. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021.

- ↑ Edge (June 25, 2007). "The Nintendo Years". Next-Gen.biz. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "CD BackUp RAM Cart". Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ludovic Drolez. "Lud's Open Source Corner". Archived from the original on March 9, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Renesas Technology and Hitachi Announce Development of SH-2A 32-Bit RISC CPUCore for High-Performance Embedded Sysytems" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 MacDonald, Charles (August 10, 2000). "Sega Genesis VDP documentation". Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ↑ "SSP1601" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Sega-16 – Sega's SVP Chip: The Road Not Taken?". Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Sega 32x Graphics". Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "SNES Graphics Information". Archived from the original on December 15, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Datasheet ersinelektronik.com Archived February 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Capcom Cx4 – Hitachi HG51B169 in SNES Development". Super Nintendo Development Wiki. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "A Super FX FAQ". Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 MacDonald, Charles. "Neo*Geo MVS Hardware Notes". Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ↑ "GPU". Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Category:Chips". Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Mame/Sn76496.c at master · mamedev/Mame · GitHub". GitHub. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Mega Drive PCB revisions – Sega Retro". Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Sega Genesis hardware notes". March 18, 2014. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014.

- ↑ "notaz's SVP doc". Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- 1 2 MacDonald, Charles (February 28, 2002). "TurboGrafx-16 Hardware Notes". Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ↑ "Street Fighter II CE Comparison Backgrounds Main". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Video Games, Cheats, Guides, Codes, Reviews – GamesRadar". Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "TASVideos". Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "How to program the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive". Archived from the original on January 22, 2005. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Charles MacDonald. "Sega Master System VDP documentation". Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- 1 2 "Sega Programming FAQ October 18, 1995, Sixth Edition – Final". Archived from the original on January 22, 2005. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sega Genesis vs Super Nintendo - www.gamepilgrimage.com". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sega 32X Technical Specifications". Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Sega CD programming FAQ". December 6, 1998. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ↑ "JAMMAPARTS.COM – Sega CD Detailed Technical Specifications". Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Technical Specifications". Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ↑ "DMA". Segaretro+. March 13, 2017. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Game Pilgrimage". Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Unit service manual gamesx.com Archived May 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Aly James. "FM-Drive 2612 VST User Manual 1.2" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- 1 2 "YM2610". Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Arcade Card Pro". PC-Engine dev. March 16, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Sega CD - www.segaretro.org". Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ↑ "OKI Semiconductor MSM5205" (PDF). console5.com. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ↑ "MSM5205". Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Archived October 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "MSM5205". Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Super NES". Classic Systems. Nintendo. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Yearly market report". Famitsu Weekly (in Japanese) (392): 8. June 21, 1996.

- ↑ Zackariasson, Peter; Wilson, Timothy L.; Ernkvist, Mirko (2012). "Console Hardware: The Development of Nintendo Wii". The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-80383-1.

- ↑ "Majesco Sales – Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ↑ Théo Azevedo (July 30, 2012). "Vinte anos depois, Master System e Mega Drive vendem 150 mil unidades por ano no Brasil" (in Portuguese). UOL. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

Base instalada: 5 milhões de Master System; 3 milhões de Mega Drive

- ↑ Sponsel, Sebastian (November 16, 2015). "Interview: Stefano Arnhold (Tectoy)". Sega-16. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Blake Snow (July 30, 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 8, 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Finance & Business". Screen Digest. March 1995. pp. 56–62. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ↑ "Weekly Famitsu Express". Famitsu (in Japanese). Vol. 11, no. 392. June 21, 1996. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ↑ "Hardware Totals". Game Data Library. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- 1 2 "Tokyorama". Consoles + (in French). No. 73. February 1998. pp. 46–7. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Consoles +, Archived November 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Stuart, Keith (2014). Sega Mega Drive Collected Works. Read-Only Memory. ISBN 9780957576810.

Finally with regards the launch of the 32X Shinobu Toyoda of Sega of America recalls, "We had an inventory problem. Behind the scenes, Nakayama wanted us to sell a million units in the US in the first year. Kalinske and I said we could only sell 600,000. We shook hands on a compromise - 800,000. At the end of the year we had managed to shift 600,000 as estimated, so ended up with 200,000 units in our warehouse, which we had to sell to retailers at a steep discount to get rid of the inventory."

- ↑ "The Atari Lynx". ataritimes.com. 2006. Archived from the original on August 10, 2006. Retrieved August 20, 2006.

- ↑ Beuscher, Dave. "allgame ( Atari Lynx > Overview )". Allgame. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

One drawback to the Lynx system is its power consumption. It requires 6 AA batteries, which allow four to five hours of game play. The Nintendo Game Boy provides close to 35 hours use before new batteries are necessary.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blake Snow (July 30, 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Handhelds of All Time". GamePro.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ Bauscher, Dave. "allgame ( Sega Game Gear > Overview )". Allgame. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

While this feature is not included on the Game Boy it does provide a disadvantage – the Game Gear requires 6 AA batteries that only last up to six hours. The Nintendo Game Boy only requires 4 AA batteries and is capable of providing up to 35 hours of play.

- ↑ "Game Boy History". Nintendo. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ↑ Douglas C. McGill (June 5, 1989). "Now, Video Game Players Can Take Show on the Road". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ↑ AU = 1850-1901: McLean, I.W. (1999), Consumer Prices and Expenditure Patterns in Australia 1850–1914. Australian Economic History Review, 39: 1-28 (taken W6 series from Table A1, which represents the average inflation in all of Australian colonies). For later years, calculated using the pre-decimal inflation calculator provided by the Reserve Bank of Australia for each year, input: £94 8s (94.40 Australian pounds in decimal values), start year: 1901.

- ↑ Melanson, Donald (March 3, 2006). "A Brief History of Handheld Video Games". Engadget. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ "PC-Engine". pc-engine. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. April 26, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Game Boy". A Brief History of Game Console Warfare. BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Did you know?". Nintendo. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Japan Platinum Game Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ↑ "US Platinum Videogame Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on April 21, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ↑ Gamate Archive Archived May 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Video Game Gazette. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ↑ IGN staff (2006). "The Top 100 Games Ever". IGN. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ IGN staff (2007). "The Top 100 Games Ever". IGN. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ IGN staff (2008). "IGN Top 100 Games 2008 – 2 Chrono Trigger". IGN. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ GameSpot editorial team, ed. (April 17, 2006). "The Greatest Games of All Time". GameSpot. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Campbell, Colin (March 3, 2006). "Japan Votes on All Time Top 100". Edge. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Ashcraft, Brian (March 6, 2008). "Dengeki Readers Say Fav 2007 Game, Fav of All Time". Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "The 100 best games of all time". GamesRadar. April 20, 2012. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. p. 497. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (October 9, 2006). "SOMETIMES THE BEST". Sad Sam's Place. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ↑ GameSpot Staff (December 2001). "GameSpot's Best and Worst of 2001: Best Fighting Game Winner". GameSpot. Archived from the original on April 13, 2002.

- ↑ Thomas, Lucas (December 11, 2006). "Gunstar Heroes Virtual Console Review". IGN. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 407–410. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ "100 Games Of All Time". gamers.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2003. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 466–80. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ↑ Semrad, Steve (February 2, 2006). "The Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Kaiser, Rowan (July 22, 2011). "RPG Pillars: Phantasy Star II". GamePro. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Kasavin, Greg. "The Greatest Games of All Time: Phantasy Star II – Features at GameSpot". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 18, 2005. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Time Machine: Phantasy Star". ComputerAndVideoGames.com. January 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 428–431. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ "Street Fighter II: The World Warrior (Game) – Giant Bomb". www.giantbomb.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ↑ "CAPCOM – Platinum Titles". Archived from the original on December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Thomas, Lucas M. (May 30, 2007). "Streets of Rage 2 Review: The definitive console brawler". IGN. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Super Monaco GP – Sega Megadrive – Mean Machines review". Meanmachinesmag.co.uk. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ Harris, Craig (September 24, 2002). "Yoshi's Island: Super Mario Advance 3". IGN.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Legend of Zelda—A link to the Past". Ludogo. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

- ↑ Gouskos, Carrie (March 14, 2006). "The Greatest Games of All-Time: The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ Nintendo (April 13, 1992). The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (SNES). Nintendo.

- ↑ Nintendo (December 2, 2002). The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past & Four Swords (Game Boy Advance). Nintendo.

- ↑ Arakawa, M. (1992). The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past Nintendo Player's Strategy Guide. Nintendo. ASIN B000AMPXNM.

- ↑ Stratton, Bryan (December 10, 2002). The Legend of Zelda — A Link to the Past. Prima Games. ISBN 0-7615-4118-7.