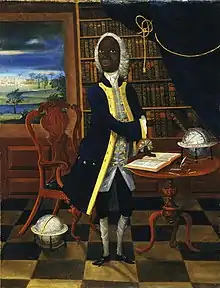

Francis Williams (c. 1690 – c. 1770) was a Jamaican scholar and poet who was one of the most notable free black people in Jamaica. Born in Kingston, Jamaica into a slaveholding family, Williams subsequently travelled to England where he officially became a British subject. After returning to Jamaica, he established a free school for free people of color in Jamaica.

Early life

Francis Williams was born c. 1690 in the English colony of Jamaica to John and Dorothy Williams, both of whom were free people of color. John had been emancipated in 1699 through the will and testament of his former enslaver.[1] The Williams family's status as free, property-owning black people set them apart from other Jamaican inhabitants, who were at the time mostly white colonists and enslaved Africans. Eventually, the Williams family property expanded to include both land and slaves. Though it was rare for black people in the 18th century to receive an education, Francis Williams and his siblings were able to afford schooling due to their father's wealth. Francis travelled to Europe, where he was reported to be in 1721.[2]: 220–221

In England

Francis was also officially made a British subject, and took the oath of citizenship in 1723.[1] Some, like Edward Long, reported that Francis Williams was the beneficiary of a social experiment devised by John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu to determine whether adequate education could lead Williams to match the intellectual achievements of his white contemporaries. This story holds that the Duke paid for Williams to attend an English grammar school and then continue at the University of Cambridge, a narrative likely originating from Montagu's relationships with Job Ben Solomon and Ignatius Sancho. However, Cambridge has no record of Williams' attendance; furthermore the Williams family's wealth could have easily supported his overseas education without the Duke's sponsorship.[3]

In Jamaica

In the 1720s, Williams returned to Jamaica, where he set up a free school for black children. In 18th-century Jamaica, most free schools were only open to the children of poor white inhabitants. Wealthy planters had bequeathed property and funds to establish foundations to educate poor white children and coloureds who could be classified as white.[4] In his school, Williams taught reading, writing, Latin and mathematics.[3] Supporters of slavery, such as Long, tried to downplay the educational accomplishments of Williams.[5] Long's History of Jamaica contains a note about the possible attribution of "Welcome, Brother Debtor", a folk tune that gained popularity in Britain during the 18th century, to Williams or to Wetenhall Wilkes.[6]

In Jamaica, Williams kept enslaved people he inherited from his father.[3] He also encountered discrimination: In 1724, a white planter named William Brodrick insulted Williams, calling him a "black dog", whereupon Williams reacted by calling Brodrick a "white dog" several times. Brodrick punched Williams, as a result of which his "mouth was bloody", but Williams retaliated, after which Brodrick's "shirt and neckcloth had been tore (sic) by the said Williams". Williams insisted that since he was a free black man, he could not be tried for assault, as would have been the case with black slaves who hit a white man, because he was defending himself.[1]

The Assembly, which comprised elected white planters, was alarmed at the success with which Williams argued his case, and how he secured the dismissal of Brodrick's attempts to prosecute him. Complaining that "Williams's behaviour is of great encouragement to the negroes of the island in general", the Assembly then decided to "bring in a bill to reduce the said Francis Williams to the state of other free negroes in this island". This legislation made it illegal for any black person in Jamaica to strike a white person, even in self-defence.[1]

Poetry

- "An Ode to George Haldane" (excerpt)

Rash councils now, with each malignant plan,

Each faction, in that evil hour began,

At your approach are in confusion fled,

Nor while you rule, shall raise their dastard head.

Alike the master and the slave shall see

Their neck reliv'd, the yoke unbound by thee.

- "Welcome, welcome Brother Debtor" (excerpt)

What was it made great Alexander

Weep at his unfriendly fate

twas because he cou'd not Wander

beyond the World's strong Prison Gate

For the World is also bounded

by the heavens and Stars above

Why should We then be confounded

Since there's nothing free but Jove.[7]

See also

- Black British elite, Williams' class in Britain

- Ignatius Sancho, another protégé of the Montagu family

- Phillis Wheatley, another early Black poet writing in English contemporaneously

References

- 1 2 3 4 Journals of the Assembly of Jamaica, Vol. 2, 19 November 1724, pp. 509–512.

- ↑ Carretta, Vincent (2003). "Who was Francis Williams?". Early American Literature. 38 (2): 213–237. doi:10.1353/eal.2003.0025. JSTOR 25057313. S2CID 162357487.

- 1 2 3 "Francis Williams – A Portrait of an Early Black Writer". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ King, Ruby, "Education in the British Caribbean: The Legacy of the Nineteenth Century". In ErrolMiller (ed.), Educational reform in the Commonwealth Caribbean, 1999, pp. 25–45.

- ↑ Gerzina, Gretchen, Black England, London: John Murray, 1995, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Long, Edward. The History of Jamaica: Or, General Survey of the Ancient and Modern State of that Island; with Reflections on Its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government, Lowndes, 1774, p. 476.

- ↑ D'Costa, Jean. "Oral Literature, Formal Literature: The Formation of Genre in Eighteenth-Century Jamaica", Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 27, no. 4: African-American Culture in the Eighteenth-Century, Summer 1994 (pp. 663–676), p. 668. JSTOR.

External links

- Ronnick, Michele Valerie. “Francis Williams: An Eighteenth-Century Tertium Quid.” Negro History Bulletin, vol. 61, no. 2, 1998, pp. 19–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24767367.

- Williams, Francis. "Carmen, or, An Ode", in Thomas W. Krise, Caribbeana: An Anthology of English Literature, 1657-1777, The University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 315–317. ISBN 978-0226453927

- Mathematicians of the African Diaspora, State University of New York at Buffalo.

- "Francis Williams, the Scholar of Jamaica". Victoria and Albert Museum.