Franklin Sousley | |

|---|---|

Sousley in 1944 | |

| Born | September 19, 1925 Hill Top, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | March 21, 1945 (aged 19) Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, Japanese Empire † |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1944–1945 |

| Rank | Private First Class |

| Unit | 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Purple Heart Medal Combat Action Ribbon |

Franklin Runyon Sousley (September 19, 1925 – March 21, 1945) was a United States Marine who was killed in action during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. He was one of the six marines who raised the second of two U.S. flags on top of Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945, as shown in the iconic photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.

The first flag raised and flown over the mountain at the south end of Iwo Jima was regarded to be too small to be seen by the thousands of Marines fighting on the other side of Iwo Jima, so it was replaced on the same day by a larger one. Although there were photographs taken of the first flag flying on Mount Suribachi after it was captured, there was no single photograph taken of Marines raising the flag. The second flag raising became famous and took precedence over the first flag raising after the photograph of it appeared worldwide in newspapers. The second flag raising was also filmed in color.[2]

The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, was modeled after the historic photograph of six Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima.

Early life

Sousley was born in Hill Top, Kentucky, the second child born to Merle Duke Sousley (1899–1934) and Goldie Mitchell (November 9, 1904 – March 14, 1988). When he was two years old, his five-year-old brother, Malcolm Brooks Sousley (November 24, 1923 – May 30, 1928), died due to appendicitis. Franklin attended a two-room schoolhouse in nearby Elizaville, and attended Fleming County High School in nearby Flemingsburg from ninth to twelfth grade. His younger brother Julian was born in May 1933, and his father died due to diabetes complications a year later, at age 35. At only nine years old, Franklin was the sole male-figure in the family, and assisted his mother in raising Julian. Sousley graduated from Fleming High School in May 1943, and resided in Dayton, Ohio as a worker in a refrigerator factory.

World War II

U.S. Marine Corps

Sousley received his draft notice, and chose to join the United States Marine Corps on January 5, 1944. He was sent to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, California. On March 15, he joined E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, Fifth Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California. In September, the 5th Division was sent to Hawaii for more training to prepare for the invasion of Iwo Jima. On November 22, he was promoted to private first class.[3]

Battle of Iwo Jima

Private First Class Sousley landed with his unit at the southeast end of Iwo Jima near Mount Suribachi which was the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines objective on February 19, 1945, and fought in the battle for the capture of the island.

First flag-raising

On the morning of February 23, Lieutenant Colonel Chandler W. Johnson, commander of the Second Battalion, 28th Marines, ordered E Company's executive officer, First Lieutenant Harold Schrier, to take a platoon-size patrol up 556-foot high Mount Suribachi to seize and occupy the crest, and if possible, raise the battalion's flag to signal the summit was secure. E Company's Commander Captain Dave Severance assembled the remainder of his Third Platoon and members from the battalion to form a 40-man patrol. At 8:30 a.m., the patrol started climbing the volcano. When the patrol reached the rim of the crater a brief firefight developed. Once they overcame the Japanese they secured the summit. A Japanese steel pipe was found for use as a flagpole and the flag was attached to it. The flag was then raised by Lt. Schrier, Platoon Sergeant Ernest Thomas, Sergeant Henry Hansen,[4] and Corporal Charles Lindberg at approximately 10:30 a.m.[5] Seeing the national colors flying caused loud cheering with some gunfire from the Marines, sailors, and Coast Guardsmen on the beach below and from the men on the ships near and docked at the beach. The men at, around, and holding the flagstaff were photographed several times by Staff Sgt. Louis R. Lowery, a photographer with Leatherneck magazine who accompanied the patrol up the mountain. Platoon Sgt. Thomas was killed on Iwo Jima on March 3, and Sgt. Hansen was killed on March 1

Second flag-raising

Lt. Col. Johnson decided that a larger flag should be taken up and flown on Mount Suribachi after he determined that the battalion's flag was too small to be seen by the thousands of Marines fighting on the other side of the mountain. Around noon, Marine Sergeant Michael Strank, a squad leader of Second Platoon, Easy Company, was ordered by his Company Commander Captain Dave Severance, to take three Marines from his rifle squad and raise a larger flag on top of Mount Suribachi. Sgt. Strank chose Corporal Harlon Block, Private First Class Ira Hayes, and Pfc. Sousley. On the way up the four Marines took telephone communication wire (or supplies). Private First Class Rene Gagnon, the Second Battalion's runner (messenger) for Easy Company, was ordered by Lt. Col. Johnson to take the replacement flag up the mountain and return with the first flag.

Once on top, Sgt. Strank ordered Pfc. Hayes and Pfc. Sousley to find a steel pipe to attach the replacement flag unto. A Japanese iron pipe was found and the flag attached to it. As Sgt. Strank and his three Marines were about to raise the flagstaff, he yelled out to two nearby Marines to help them raise the heavy flagstaff. Under Lt. Schrier's orders, Sgt. Strank, Cpl. Block (incorrectly identified as Sgt. Hansen until January 1947), Pfc. Hayes, Pfc. Sousley, Private First Class Harold Schultz,[6] and Private First Class Harold Keller[7] raised the second flag at approximately 1 p.m. as the first flagstaff was lowered. Pfc. Schultz and Pfc. Keller were both members of Lt. Schrier's patrol. Due to the high winds on Mount Suribachi, Navy Corpsman John Bradley helped some Marines make the flagstaff stay vertical. Afterwards, rocks were added to the bottom of the flagstaff which was then stabilized by three guy-ropes. The second raising was immortalized by the black-and-white photograph of the flag raising by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press; On June 23, 2016, Harold Keller was identified as Sousley in the photo and Sousley was identified as Navy Corpsman John Bradley in the photo (Bradley was no longer determined to be in the photo).[6] Marine photographer Sergeant Bill Genaust also filmed the second flag raising in color.[2]

On March 14, another American flag was officially raised up a flagpole by two Marines under the orders of Lt. Gen. Holland Smith during a ceremony at the V Amphibious Corps command post on the other side of Mount Suribachi where the 3rd Marine Division troops were located. The flag flying on the summit of Mount Suribachi since February 23 was taken down. On March 26, 1945, the island was considered secure and the battle of Iwo Jima was officially ended. The 28th Marines left Iwo Jima on March 27 and returned to Hawaii to the 5th Marine Division training camp. Lt. Col. Johnson was killed on Iwo Jima on March 2, Sgt. Genaust was killed on March 4, Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block were killed on March 1, and Pfc. Sousley was killed on March 21.

Death

On March 20, 1945, the Marine Corps was ordered by President Franklin Roosevelt to send the flag raisers in Rosenthal's photo after the battle to Washington D.C. as a public morale factor and to participate in a much needed war bond selling tour.[8] Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block were killed on March 1. Pfc. Sousley was killed on March 21. The book Flags of Our Fathers (2000) by James Bradley (son of Navy corpsman John Bradley who accompanied the 40-man patrol up the mountain), says Pfc. Sousley was shot in the back by a Japanese sniper as he was walking down an open road which was a known area of enemy sniper fire, and speculated that he lost his focus or thought the Japanese had stopped firing. According to the book, a fellow Marine saw Sousley lying on the ground and asked, "How bad are you hit?" Sousley's last words were, "Not bad, I can't feel a thing." He then died of his injuries. However, Rene Gagnon, who knew Sousley personally for several months and saw Sousley the day he was killed, had signed an affidavit for the Marine Corps reporting that Sousley was killed instantly.

Pfc. Sousley's body was buried at the 5th Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima, on March 25, 1945. A service was held there in the morning of March 26 by the division's surviving Marines, which included Ira Hayes and other members of Sousley's platoon and company before they departed Iwo Jima the next day. Sousley's remains were reinterred on May 8, 1948,[1] in Elizaville Cemetery in Fleming County, Kentucky.

Marine Corps War Memorial

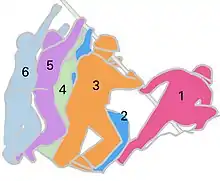

#1, Cpl. Harlon Block (KIA)

#2, Pfc. Harold Keller

#3, Pfc. Franklin Sousley (KIA)

#4, Sgt. Michael Strank (KIA)

#5, Pfc. Harold Schultz

#6, Pfc. Ira Hayes

The Marine Corps War Memorial (also known as the Iwo Jima Memorial) in Arlington, Virginia, was dedicated on November 10, 1954.[9] The monument was sculpted by Felix de Weldon from the image of the second flag raising on Mount Suribachi. Due to some incorrect identifications of the second flag raisers, Sousley is depicted as the third instead of the fifth 32-foot (9.8 M) bronze statue from the bottom of the flagstaff since June 13, 2016 (Harold Schultz is depicted as the fifth bronze statue).[6] The Memorial was turned over to the National Park Service in 1955.

During the dedication, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sat upfront with Vice President Richard Nixon, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Anderson, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Orme Lewis, and General Lemuel C. Shepherd, the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps.[10] Ira Hayes, one of the three surviving flag raisers depicted on the monument was also seated upfront with John Bradley (incorrectly identified as a flag raiser until June 2016),[6][11] Rene Gagnon (incorrectly identified as a flag raiser until October 2019),[12] Mrs. Goldie Price (Mother of Franklin Sousley), Mrs. Martha Strank, and Mrs. Ada Belle Block.[11] Those giving remarks at the dedication included Robert Anderson, Chairman of Day; Colonel J.W. Moreau, U.S. Marine Corps (Retired), President, Marine Corps War Memorial Foundation; General Shepherd, who presented the memorial to the American people; Felix de Weldon; and Richard Nixon, who gave the dedication address.[13][10] Inscribed on the memorial are the following words:

- In Honor And Memory Of The Men of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775

Portrayal in film

In the 1961 film The Outsider, starring Tony Curtis as Ira Hayes, the fictional character James B. Sorenson (Hayes's Marine buddy in the movie), portrayed by actor James Franciscus, was a composite based primarily on Franklin Sousley.

In the 2006 film Flags of Our Fathers, about the six flag raisers on Iwo Jima, Franklin Sousley was portrayed by actor Joseph Michael Cross. The film is based on the 2000 book of the same title.

Military awards

Sousley's military decorations and awards:

| Purple Heart Medal | Combat Action Ribbon[14] | Navy Presidential Unit Citation |

| American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one 3⁄16" bronze star | World War II Victory Medal |

Note: The Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal required 4 years service during the World War II time period.

Honors

There is a small Franklin Sousley memorial in the Fleming County Public Library, in Flemingsburg, Kentucky. Additionally in Flemingsburg, there is the Franklin Sousley Museum located at Camp Sousley.[15]

The VA medical center in Lexington, Kentucky was renamed for Franklin R. Sousley in 2018.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Marine Corps University > Research > Marine Corps History Division > People > Who's Who in Marine Corps History > Scannell - Upshur > Private First Class Franklin Runyon Sousley".

- 1 2 3 You Tube, Smithsonian Channel, 2008 Documentary (Genaust films) "Shooting Iwo Jima" Retrieved March 14, 2020

- ↑ "Marine Corps University > Research > Marine Corps History Division > People > Who's Who in Marine Corps History > Scannell - Upshur > Private First Class Franklin Runyon Sousley".

- ↑ Rural Florida Living. CBS Radio interview by Dan Pryor with flag raiser Ernest "Boots" Thomas on February 25, 1945 aboard the USS Eldorado (AGC-11): "Three of us actually raised the flag"

- ↑ Brown, Rodney (2019). Iwo Jima Monuments, The Untold Story. War Museum. ISBN 978-1-7334294-3-6. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- ↑ "Marines correct 74-year-old Iwo Jima error". NBC News.

- ↑ The Mighty Seventh War Loan: "Keep Him Flying || Bucknell University". Archived from the original on 2013-04-06. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- ↑ The Marine Corps War Memorial Marine Barracks Washington, D.C.

- 1 2 Brown, Rodney (2019). Iwo Jima Monuments, The Untold Story. War Museum. ISBN 978-1-7334294-3-6. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- 1 2 "Memorial honoring Marines dedicated". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 1.

- ↑ "Marines correct 74-year-old Iwo Jima error". NBC News.

- ↑ "Marine monument seen as symbol of hopes, dreams". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 2.

- ↑ Combat Action Ribbon (1969): Retroactive from December 7, 1941: Public Law 106-65, October 5, 1999, 113 STAT 508, Sec. 564

- ↑ "Camp Sousley | In Honor of Franklin Sousley". campsousley.com. Retrieved 2018-03-06.