Franklin bells (also known as lightning bells) are an early demonstration of electric charge designed to work with a Leyden jar or a Lightning rod. Franklin bells are only a qualitative indicator of electric charge and were used for simple demonstrations rather than research. The bells are an adaptation to the first device that converted electrical energy into mechanical energy in the form of continuous mechanical motion, in this case, the moving of a bell clapper back and forth between two oppositely charged bells.[1]

History

Scientific investigation of the phenomena of lightning originates with Benjamin Franklin. He accumulated analogical evidence favoring the supposition that lightning must be an electrical discharge on a large scale.[2] In the mid-18th century, lightning strikes were a serious problem for buildings and structures, causing damage and sometimes even fires. Franklin set out to understand the nature of lightning and to find ways to protect buildings from its destructive effects.[3] He began his investigations by observing how lightning strikes affected various types of buildings. He noticed that some buildings were more vulnerable to lightning strikes than others and that buildings with sharp pointed roofs were more likely to be struck than those with flat roofs. He also observed that lightning seemed to follow conductive paths, such as metal rods or wires, and that these paths could be used to divert lightning strikes away from buildings.[4]

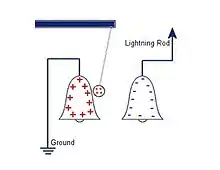

Based on these observations, Franklin developed the idea of the Lightning rod. The Lightning rod consists of a metal rod or conductor, typically made of copper or aluminum, that is mounted on the roof of a building and connected to the ground by means of a conductive wire. When lightning strikes, the rod provides a path of least resistance for the electrical charge, allowing it to be safely conducted to the ground rather than passing through the building and causing damage. The invention of the lightning rod was a significant breakthrough in the field of electrical engineering, and has saved countless buildings and lives from the destructive effects of lightning strikes.[4]

The Franklin bells were named for Benjamin Franklin, an early adopter who used it during his experimentation with electricity.[5] Its predecessor was invented by the Scottish inventor Andrew Gordon, Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Erfurt, Germany.[6] In 1742 he invented a device known as the "electric chimes", which was widely described in textbooks of electricity. Franklin made use of Gordon's idea by connecting one bell to his pointed lightning rod, attached to a chimney, and a second bell to the ground. One of his papers contains the following description:

In September 1752, I erected an iron rod to draw the lightning down into my house, in order to make some experiments on it, with two bells to give notice when the rod should be electrified. I found the bells rang sometimes when there was no lightning or thunder, but only a dark cloud over the rod; that sometimes after a flash of lightning they would suddenly stop; and at other times, when they had not rang before, they would, after a flash, suddenly begin to ring; that the electricity was sometimes very faint, so that when a small spark was obtained, another could not be got for sometime after; at other times the sparks would follow extremely quick, and once I had a continual stream from bell to bell, the size of a crow-quill. Even during the same gust there were considerable variations.[7] The frontispiece to Franklin's Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1751) shows, in the uppermost row, some of the experiments with the Leyden jar. The experiment at the extreme right demonstrates the principle of conservation of charge for the jar. The sentry-box experiment appears at the center.[8]

Through this experiment, Franklin was able to demonstrate that electricity behaves like a fluid, flowing through conductive materials and causing effects along the way. Franklin's experiment with the bells and the lightning rod was groundbreaking in its time, as it provided a clear demonstration of the nature of electricity and its properties. It helped to shape understanding of electricity as a fluid that flows through conductive materials and provided a foundation for further experiments and discoveries in the field.[9]

Franklin's experimentation with the bell setup was pivotal to discovering that electricity exists outside of lightning and thunderstorms. The bells' odd properties intrigued Franklin and fueled further hypotheses.

Design and operation

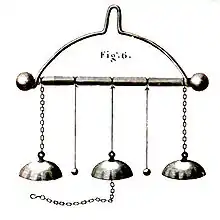

The bells consist of a metal stand with a crossbar, from which hang three bells. The outer two bells hang from conductive metal chains, while the central bell hangs from a nonconductive thread. In the spaces between these bells hang two metal clappers, small pendulums, on nonconductive threads. A short metal chain hangs from the central bell.

The system of operation of the Franklin clock considers that the electrostatic force generated by an electric field is used to move the pendulums that strike two metal bells.[10][11] The Franklin bells uses a metal rod as a lightning rod to attract current. One bell is connected to the lightning rod and the other bell is connected to the ground. A metal battering ram is suspended between the two bells by an insulated wire. The negatively charged clouds before the thunderstorm make the lightning rod negatively charged, and also make the bell connected to it negatively charged. The metal ball is attracted and crashes into the fully charged bell. When the ball hits the first bell, it will be charged with the same potential and will therefore be repelled again. Since the opposite bell is reversely charged, this will also attract the ball to it. When the ball hits the second bell, the charge is transferred and the process is repeated until the charges are balanced again.[12][13] Before the storm, the device would ring to remind Franklin, who had been obsessed with the study of lightning, urging him to chase the lightning.

Modern Impact

Benjamin Franklin's experiment with bells and a Lightning rod has remained a popular example of electric phenomena in modern times. The experiment has been adapted and updated, and is now commonly used in classrooms and demonstrations to illustrate a variety of concepts related to electricity.[1]

For instance, the experiment can be used to demonstrate the concept of electric current and how it flows through a conductor. By connecting the bells with metal wires and charging the lightning rod, students can see the flow of electric charges through the wires and observe the resulting electromagnetic effects that cause the bells to ring.[6]

The experiment can also be used to illustrate the properties of static electricity, and how it can be conducted through metal wires to create an electric current. By rubbing a balloon or other object to create a static charge, and then using the charge to activate the bells, students can see the effects of static electricity and learn how it can be harnessed and utilized.[6] The Franklin Bell is now a common electrical experiment demonstration in high school and introductory college physics courses.

See also

- Oxford Electric Bell, a set of electrostatic bells in the University of Oxford, has been ringing continuously since 1840.

- Lightning-prediction system

- Lightning rod

References

- 1 2 Krotkov, R. V.; Tuominen, M. T.; Breuer, M. L. (2001). ""Franklin's Bells" and charge transport as an undergraduate lab". American Journal of Physics. 69 (1): 50–55. Bibcode:2001AmJPh..69...50K. doi:10.1119/1.1313519. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ↑ Cohen, I. Bernard (1995). Science and The Founding Father. NORTON. p. 148. ISBN 0-393-03501-8.

- ↑ Cohen, I. Bernard (1952). "The Two Hundredth Anniversary of Benjamin Franklin's Two Lightning Experiments and the Introduction of the Lightning Rod". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 96 (3): 331–366. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 3143838.

- 1 2 Krider, E. Philip (2006). "Benjamin Franklin and lightning rods". Physics Today. 59 (1): 42–48. Bibcode:2006PhT....59a..42K. doi:10.1063/1.2180176. ISSN 0031-9228. S2CID 110623159.

- ↑ Cohen, I. Bernard (1995). Science and the founding Fathers. NORTON. p. 143. ISBN 0-393-03501-8.

- 1 2 3 Collins, Nick (2013). Electronic music. Margaret Schedel, Scott, November 26- Wilson. Cambridge. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-107-01093-2. OCLC 822560190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Franklin, Benjamin (September 1753). "From Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, September 1753". National Archives.

- ↑ Cohen, I. Bernard (1995). Science and The Founding Father. NORTON. p. 145. I

- ↑ O'Reilly, Michael Francis (1909). Makers of electricity. Internet Archive. New York : Fordham university press.

- ↑ Resnick, R., Halliday, D., Krane, K. S., Física Vol.2, 5ª ed. (CECSA México, 2004)

- ↑ Sears, F.W., Zemansky, M.W., Young, H.D., Freedman R.A.: Física Universitaria, 12ª Edición.Vol. 1 y 2. (Addison-Wesley-Longman/Pearson Education, 1980)

- ↑ S. C. Firmenich, "Franklin’s Bells: Converting Electrical Energy Into Continuous Mechanical Motion," 2021 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC), Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021, pp. 222-222, doi:10.1109/ISEC52395.2021.9763971.

- ↑ Castro-Arce, L., Isasi-S, L. F., Figueroa-N, C., Molinar-T, M. E., & Campos-G, J. C. (2015). Electric Discharge System Based on Franklin Bells. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST), 2(6), 1567. Retrieved from http://www.jmest.org/wp-content/uploads/JMESTN42350860.pdf

External links

- Ben Franklin's Lightning Bells(Franklin Institute)

- Franklin’s Bells (Gordon’s Bells) (PV Scientific Instruments)

- "Franklin’s Bells" and charge transport as an undergraduate lab (American Journal of Physics)

- Franklin's Bells (Research Media & Cybernetics)