Frederick Charles Victor Laws | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | "Daddy" |

| Born | 29 November 1887[1][2] Thetford, Norfolk, England[1] |

| Died | 27 October 1975 (aged 87)[3] |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1905–1923 1939–1946 |

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Unit | Coldstream Guards No. 1 Balloon Company No. 3 Squadron RFC Lincolnshire Regiment |

| Commands held | RAF School of Photography |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Order of the Bath Order of the British Empire Legion of Merit (USA) |

Group Captain Frederick Charles Victor Laws CB CBE (29 November 1887 – 27 October 1975), was an officer in the Royal Air Force, an aerial surveyor, and the founder and most prominent pioneer of British aerial reconnaissance.

Early military service

Laws enlisted into the Coldstream Guards on 22 February 1905, and was stationed in Egypt and Sudan until 1912. He supplemented his income by taking photographs with his Kodak Bullseye box camera and selling them to his fellow soldiers. He later applied for an assignment to the signalling section, mainly in order to obtain access to the unit's darkroom facilities, and also experimented with communicating with aircraft by heliograph.[4]

Laws returned to England in 1912, and in December "presented himself for a trade test at the headquarters of the Military Wing of the [just created] Royal Flying Corps, then located at South Farnborough." He passed and was graded air mechanic 1st class, but he "had a feeling that he knew more about the subject than did his examiner." Within months, Laws was promoted to sergeant and put in charge of the photographic section of his squadron.[5]

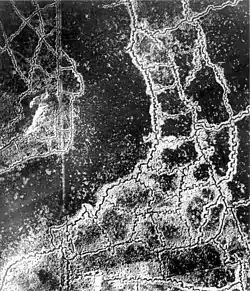

Laws was first posted to the No. 1 Balloon Company and began to take aerial photographs from the Army airship Beta. Laws discovered that vertical photos taken with 60% overlap could be used to create a stereoscopic effect when viewed in a stereoscope, thus creating a perception of depth that could aid in cartography and in intelligence derived from aerial images.[6]

Next year, Laws took similar photos from kites, Bleriot and Farman aircraft and other types just then being completed by the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. He also conducted camera experiments at the second RFC site at Salisbury Plain. As dirigibles were then allocated to the Royal Navy, Laws was chosen to help form an aerial reconnaissance unit of fixed-wing aircraft, at that time consisting in part of B.E.2 biplanes from the Royal Aircraft Factory. This No. 2 (Aeroplane) Company later became No. 3 Squadron RFC, the first heavier-than-air British unit.

First World War

Still, in 1914, the British entered into aerial reconnaissance in the First World War with no credible heavier-than-air capability. The shortage was in optics and cameras as well as aircraft and pilots. Laws and his collaborators first created the A-camera, then later the L-camera (for Laws), which became the standard British airborne camera, usually fixed on the side of the fuselage pointing down. With Lieutenant John Moore-Brabazon, another aviation pioneer, Laws built the L/B camera for special situations, introduced late in the war.[7]

Laws went to France with No. 3 Squadron RFC and organized the air reconnaissance sections.[8] In February 1915 he was posted to the Experimental Photographic Section, 1st Wing, and also qualified as an observer and pilot.[4]

On 7 November 1915, Laws was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Lincolnshire Regiment, seconded for service with the Royal Flying Corps, and appointed an Assistant Equipment Officer,[9][10] posted to the RFC School of Photography at Farnborough.[4]

On 1 June 1916 he was appointed an Equipment Officer with the temporary rank of captain,[11] and on 22 December 1916 he was appointed a Park Commander with the temporary rank of major,[12] and served at the Headquarters of the Royal Flying Corps on the Western Front until the armistice.[4]

By the end of the war, Laws was recognized as "the most experienced aerial photographic adviser in England and possibly the world."[8] On 1 January 1919 he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, in recognition of his "...valuable services rendered in connection with the War..."[13] Two weeks later, on 15 January, he married Madeleine Grace Mathews Withers at St. Michael's Church, Chester Square, London.[14]

Inter-war career

On 1 August 1919 Laws was granted a permanent commission in the RAF with the rank of major (squadron leader),[15] resigning his army commission the same day.[16] He served in the Directorate of Research at the Air Ministry from 1919 to 1923,[4] where he led the development of the F8 and F24 cameras, which became standard RAF equipment throughout the next war.[17] He was then appointed commander of the RAF School of Photography at Farnborough.[4] On 1 January 1927 he was promoted to wing commander.[18] Disappointed with the peacetime eclipse of his speciality, Laws was placed on the retired list at his own request on 1 September 1933.[19]

In 1933–34, he was expedition leader of the aerial mapping of Western Australia for the H. Hemmings company, an enormous task using two DH.84 Dragons.[7][20] He also worked for the Western Mining Corporation of Australia up to 1936, doing aerial survey work, and was a director of the camera manufacturers Williamsons from 1937 to 1939.[4]

Second World War

Laws rejoined the RAF as a wing commander at the beginning of the Second World War, and served in the Photography Section at RAF Headquarters in France until February 1940,[4] when he was appointed Deputy Director of the Directorate of Photography in the Air Ministry.[21] When his American counterpart, Colonel George Goddard, met with Laws in London, Goddard described him as "short in stature, very proper in manner, just as wary and sensitive as I might have been had he come prowling around my laboratory at Wright Field out to prove his goods were better than mine."[22]

On 1 January 1944, Laws was promoted to group captain.[23] On 19 September he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire, in recognition "...of services in planning the landings in Normandy..."[24] In October 1945 he was made an Officer of the Legion of Merit by the United States of America.[25] Laws reverted to the retired list on 12 May 1946, retaining the rank of group captain.[26]

Post-war career

In peacetime, Laws established himself as a leader in commercial air survey. He served as managing director of Fairey Air Surveys and the Photo Finish Recording Company from 1947 to 1963.[4]

Laws authored several articles and treatises on aerial photography.

References

- 1 2 Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910–1950

- ↑ 1939 England and Wales Register

- ↑ England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858–1995

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Laws, Frederick Charles Victor". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ↑ Laws (1959), p. 24.

- ↑ Aerial Photography, p.36.

- 1 2 Taylor (1972), p. 24.

- 1 2 Hernan (2007), p. 115.

- ↑ "No. 29398". The London Gazette. 10 December 1915. p. 12336.

- ↑ "Royal Flying Corps". Flight. VII (359): 869. 12 November 1915. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ↑ "No. 29653". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 July 1916. p. 6706.

- ↑ "No. 29910". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 January 1917. p. 808.

- ↑ "No. 31098". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1918. pp. 92–93.

- ↑ "Personals: Married". Flight. XI (538): 183. 6 February 1919. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ↑ "No. 31486". The London Gazette. 1 August 1919. pp. 9864–9865.

- ↑ "No. 31932". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 June 1920. p. 6325.

- ↑ Helman (1969), p. 79.

- ↑ "No. 33235". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1926. p. 9.

- ↑ "No. 33975". The London Gazette. 5 September 1933. p. 5802.

- ↑ Hernan (2007), p. 114.

- ↑ Helman (1969), p. 86.

- ↑ Goddard (1969), p. 287.

- ↑ "No. 36340". The London Gazette (Supplement). 18 January 1944. p. 403.

- ↑ "No. 36706". The London Gazette. 15 September 1944. p. 4325.

- ↑ "No. 37300". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 October 1945. pp. 4957–4958.

- ↑ "No. 37581". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 May 1946. p. 2554.

Bibliography

- Finnegan, Terrence (2007). Shooting the Front: Allied Aerial Reconnaissance and Photographic Interpretation on the Western Front, World War I. Washington, DC: National Defense Intelligence College. ISBN 978-1-93294-604-8.

- Goddard, George (1969). Overview: A Lifelong Adventure in Aerial Photography. Garden City: Doubleday.

- Helman, Grover (1969). Aerial Reconnaissance. New York: Macmillan.

- Hernan, Brian (2007). The Forgotten Flyer: The Story of Charles Snook. Kalamunda, Western Australia: Tangee Publishing. ISBN 978-0-97579-362-6.

- Laws, F. C. V. (April 1959). "Looking Back". Photogrammetric Record. 3 (13): 24–41. doi:10.1111/j.1477-9730.1959.tb01250.x.

- Laws, F. C. V. (1919). "Aërial Cameras". Photographic Journal (59): 192–195.

- Laws, F. C. V. (27 August 1942). "Air Photography in War". Flight. XLII (1757): 229–232. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Staerck, Chris, ed. (1998). Allied Photo Reconnaissance of WWII. San Diego: Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 978-1-57145-161-3.

- Taylor, John W. R. (1972). Spies in the Sky. London, UK: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-71100-404-7.