| Freedom Monument Brīvības piemineklis | |

|---|---|

| Riga Monument Agency Rīgas Pieminekļu aģentūra | |

| |

| For Heroes killed in action during the Latvian War of Independence | |

| Unveiled | November 18, 1935 |

| Location | 56°57′5″N 24°6′47″E / 56.95139°N 24.11306°E in Riga, Latvia |

| Designed by | Kārlis Zāle |

TĒVZEMEI UN BRĪVĪBAI | |

The Freedom Monument (Latvian: Brīvības piemineklis)[lower-alpha 1] is a monument located in Riga, Latvia, honouring soldiers killed during the Latvian War of Independence (1918–1920). It is considered an important symbol of the freedom, independence, and sovereignty of Latvia.[1] Unveiled in 1935, the 42-metre (138 ft) high monument of granite, travertine, and copper often serves as the focal point of public gatherings and official ceremonies in Riga.

The sculptures and bas-reliefs of the monument, arranged in thirteen groups, depict Latvian culture and history. The core of the monument is composed of tetragonal shapes on top of each other, decreasing in size towards the top, completed by a 19-metre (62 ft) high travertine column bearing the copper figure of Liberty lifting three gilded stars. The concept for the monument first emerged in the early 1920s when the Latvian Prime Minister, Zigfrīds Anna Meierovics, ordered rules to be drawn up for a contest for designs of a "memorial column". After several contests the monument was finally built at the beginning of the 1930s according to the scheme "Mirdzi kā zvaigzne!" ("Shine like a star!") submitted by Latvian sculptor Kārlis Zāle. Construction works were financed by private donations.

Following the Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940, Latvia was annexed by the Soviet Union and the Freedom Monument was considered for demolition, but no such move was carried out. Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina is sometimes credited for rescuing the monument, because she considered it to be of high artistic value. In 1963, when the issue of demolition was raised again, it was dismissed by Soviet authorities as the destruction of the monument would have caused deep indignation and tension in society. During the Soviet era, it remained a symbol of national independence to the general public. Indeed, on 14 June 1987, about 5,000 people gathered at the monument to lay flowers. This rally renewed the national independence movement, which culminated three years later in the re-establishment of Latvian sovereignty after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The female figure at the top of the Freedom Monument is affectionately called Milda,[2] because, according to Lithuanian author Arvydas Juozaitis, the model for the sculpture was a Lithuanian woman Milda Jasikienė, who lived in Riga.[3][4] However, the Riga Monument Agency says there are no historical records supporting this claim.[5]

Design

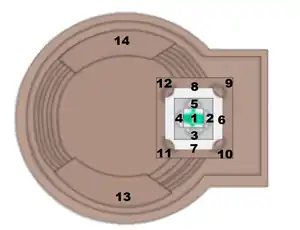

The sculptures and bas-reliefs of the Freedom Monument, arranged in thirteen groups, depict Latvian culture and history.[6] The core of the monument is composed of tetragonal shapes on top of each other, decreasing in size towards the top. A red granite staircase of ten steps, 1.8 meters (5.9 ft) in height, winds around the base of the monument between two travertine reliefs 1.7 meters (5.6 ft) high and 4.5 meters (15 ft) wide, "Latvian riflemen" (13; Latvian: Latvju strēlnieki) and "Latvian people: the Singers" (14; Latvian: Latvju tauta – dziedātāja), which decorate its 3 meters (9.8 ft) thick sides.[1] Two additional steps form a round platform, which is 28 meters (92 ft) in diameter, on which the whole monument stands. At the front of the monument this platform forms a rectangle, which is used for ceremonial proposes. The base of the monument, also made of red granite, is formed by two rectangular blocks: the lower one is a monolithic 3.5 meters (11 ft) high, 9.2 meters (30 ft) wide and 11 meters (36 ft) long, while the smaller upper block is 3.5 meters (11 ft) high, 8.5 meters (28 ft) wide and 10 meters (33 ft) long and has round niches in its corners, each containing a sculptural group of three figures. Its sides are also paneled with travertine.[7]

On the front of the monument, in between the groups "Work" (10; depicting a fisherman, a craftsman and a farmer, who stands in the middle holding a scythe decorated with oak leaves and acorns to symbolize strength and manhood) and "Guards of the Fatherland" (9; depicting an ancient Latvian warrior standing between two kneeling modern soldiers), a dedication by the Latvian writer Kārlis Skalbe is inscribed on one of the travertine panels: For Fatherland and Freedom (6; Latvian: Tēvzemei un Brīvībai).[1] On the sides the travertine panels bear two reliefs: "1905" (7; Latvian: 1905.gads in reference to the Russian Revolution of 1905), and "The Battle against the Bermontians on the Iron Bridge" (8; Latvian: Cīņa pret bermontiešiem uz Dzelzs tilta, referring to the decisive battle in Riga during the Latvian War of Independence). On the back of the monument are another two sculptural groups: "Family" (12; Latvian: Ģimene) (a mother standing between her two children) and "Scholars" (11; Latvian: Gara darbinieki (a Baltic "pagan" priest, holding a crooked stick standing between figures of modern scientist and writer).[1] On the red granite base there is yet another rectangular block, 6 meters (20 ft) high and wide, and 7.5 meters (25 ft) long, encircled by four 5.5–6 meters (18–20 ft) high gray granite sculptural groups: "Latvia" (2; Latvian: Latvija), "Lāčplēsis" (3; English: Bear-Slayer, an epic Latvian folk hero), "Vaidelotis" (5; a Baltic "pagan" priest) and "Chain breakers" (4; Latvian: Važu rāvēji) (three chained men trying to break free from their chains).[7]

The topmost block serves also as the foundation for the 19 meters (62 ft) high monolithic travertine column, which is 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) by 3 meters (9.8 ft) at the base. To the front and rear a line of glass runs along the middle of the column.[7] The column is topped by a copper figure of Liberty (1), which is 9 meters (30 ft) tall and in the form of a woman holding three gilded stars, symbolizing the constitutional districts of Latvia: Vidzeme, Latgale and Courland.[8] The whole monument is built around a frame of reinforced concrete and was originally fastened together with lead, bronze cables and lime mortar.[7] However, some of the original materials were replaced with polyurethane filler during restoration.[9] There is a room inside the Monument, accessed through a door in its rear side, which contains a staircase leading upwards in the Monument that is used for electrical installation and to provide access to the sewerage. The room cannot be accessed by the public and is used mainly as storage, however it has been proposed that the room could be redesigned forming a small exhibition, which would be used to introduce foreign officials visiting Latvia with the history of the Monument after the flower-laying ceremony.[10]

Location

The monument is located in the center of Riga on Brīvības bulvāris (Freedom Boulevard), near the old town of Riga.[8] In 1990 a section of the street around the monument, about 200 meters (660 ft) long, between Rainis and Aspazija boulevards, was pedestrianized, forming a plaza. Part of it includes a bridge over the city's canal, once a part of the city's fortification system, which was demolished in the 19th century to build the modern boulevard district.[11] The canal is 3.2 kilometers (2.0 mi) long and surrounded by parkland for half of its length.[6] The earth from the demolition of the fortifications was gathered in the park and now forms an artificial hill with a cascade of waterfalls to the north of the monument.[1] The Boulevard district east of the park is the location of several embassies and institutions, of which the closest to the Freedom Monument are the German and French embassies, the University of Latvia and Riga State Gymnasium No.1.[12]

Situated in the park near the monument to the south is the National Opera House with a flower garden and a fountain in front of it.[13] Opposite the opera house on the western part of plaza near the old town, is a small café and the Laima clock. The clock was set up in 1924, and in 1936 it was decorated with an advertisement for the Latvian confectionery brand "Laima", from which it took its name; it is a popular meeting spot.[14]

Originally it was planned that an elliptical plaza would be built around the foot of the monument, enclosed by a granite wall 1.6 meters (5.2 ft) high, with benches placed inside it, while a hedge of thujas was to be planted around the outside. This project was however not carried out in the 1930s. The idea was reconsidered in the 1980s but shelved again.[1]

Construction

The idea of building a memorial to honour soldiers killed in action during the Latvian War of Independence first emerged in the early 1920s. On 27 July 1922, the Prime Minister of Latvia, Zigfrīds Anna Meierovics, ordered rules to be drawn up for a contest for designs of a "memorial column". The winner of this contest was a scheme proposing a column 27 meters (89 ft) tall with reliefs of the official symbols of Latvia and bas-reliefs of Krišjānis Barons and Atis Kronvalds. It was later rejected after a protest from 57 artists.[1] In October 1923, a new contest was announced, using for the first time the term "Freedom Monument". The contest ended with two winners, and a new closed contest was announced in March 1925, but, due to disagreement within the jury, there was no result.[1]

Finally in October 1929, the last contest was announced. The winner was the design "Shine like a star!" (Latvian: "Mirdzi kā zvaigzne!") by sculptor Kārlis Zāle, who had had success in the previous contests as well. After minor corrections made by the author and supervising architect Ernests Štālbergs, construction began on 18 November 1931.[1] Financed by private donations, the monument was erected by the entrance to the old town, in the same place where the previous central monument of Riga, a bronze equestrian statue of Tsar Peter the Great of Russia had stood from 1910 until the outbreak of World War I.[15] It was calculated in 1935, the year when the monument was unveiled, that in four years of construction 308,000 man-hours were required to work the stone materials alone: 130 years would have been required if one person were to carry out the work using the most advanced equipment of the time. The total weight of materials used was about 2,500 tons: such a quantity of materials would have required about 200 freight cars if transported by railway.[7]

Restoration

The monument is endangered by the climate (which has caused damage by frost and rain) and by air pollution.[16] Although in 1990 the area around the monument was pedestrianized, there are still three streets carrying traffic around it.[1] High concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide have been recorded near the monument, which in combination with water cause corrosion of the fabric of the monument.[16] In addition, water has caused cracking of the reinforced concrete core and rusting of its steel reinforcements and the fastenings of the monument, which also have been worn out by constant vibrations caused by traffic.[9] The porous travertine has gradually crumbled over time and its pores have filled with soot and particles of sand, causing it to blacken and providing a habitat for small organisms, such as moss and lichens.[16] Irregular maintenance and the unskillful performance of restoration work have also contributed to the weathering of the monument. To prevent its further decay some of the fastenings were replaced with polyurethane filler and water repellent was applied to the monument during the restoration in 2001. It was also determined that maintenance should be carried out every 2 years.[9]

The monument was restored twice during the Soviet era (1962 and 1980–1981). In keeping with tradition the restorations and maintenance after the renewal of Latvia's independence are financed partly by private donations. The monument underwent major restoration in 1998–2001.[1] During this restoration the statue of Liberty and its stars were cleaned, restored and gilded anew.[17] The monument was formally re-opened on July 24, 2001.[18] The staircase, column, base and inside of the monument were restored, and the stone materials were cleaned and re-sealed. The supports of the monument were fixed to prevent subsidence. Although the restorers said at the time that the monument would withstand a hundred years without another major restoration, it was discovered a few years later that the gilding of the stars was damaged, due to the restoration technique used. The stars were restored again during maintenance and restoration in 2006; however, this restoration was rushed and there is no warranty of its quality.[19]

As of 2016 the monument is regularly monitored and its lower part is cleaned and covered with a protective coating every five years. It is planned to carry out cleaning and restoration of entire monument in 2017.[20]

Guard of honour

The guard of honour was present from the unveiling of the monument until 1940, when it was removed shortly after the occupation of Latvia.[1] It was renewed on 11 November 1992.[1] The guards are soldiers of The Guard of Honour Company of the Staff Battalion of the National Armed Forces (Latvian: Nacionālo Bruņoto spēku Štāba bataljona Goda sardzes rota).[21] The guard is not required to be on duty in bad weather conditions and if the temperatures are below −10 °C (14 °F) or above 25 °C (77 °F).[22][23] The guards work in two weekly shifts, with three or four pairs of guards taking over from each other hourly in a ceremony commanded by the chief of the guard.[22][23] Besides them there also are two watchmen in each shift, who look out for the safety of the guards of honour.[23]

Normally the guard changes every hour between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. After an hour on watch the guards have two hours free that they spend in their rooms at the Ministry of Defence.[23] Since September 2004 the guards also patrol every half hour during their watch: they march off from the base of the monument and march twice along each side of it and then return to their posts.[24] The guards are required to be at least 1.82 meters (6.0 ft) tall and in good health, as they are required to stand without moving for half an hour.[21][22]

Political significance

After the end of World War II, there were plans to demolish the monument, although little written evidence is available to historians and research is largely based on oral testimony.[15] On September 29, 1949 (although according to oral testimony, the issue was first raised as early as October 1944) the Council of People's Commissars of the Latvian SSR proposed the restoration of the statue of Tsar Peter the Great of Russia. While they did not expressly call for the demolition of the Freedom Monument, the only way to restore the statue to its original position would have been to tear down the monument. The result of the debate is unrecorded, but since the monument still stands the proposition was presumably rejected.[15] The Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina (1889–1953; designer of the monumental sculpture Worker and Kolkhoz Woman) is sometimes credited with the rescue of the monument, although there is no written evidence to support the fact.[25] According to her son, she took part in a meeting where the fate of the monument was discussed, at which her opinion, as reported by her son, was that the monument was of very high artistic value and that its demolition might hurt the most sacred feelings of the Latvian people.[15]

The Freedom Monument remained, but its symbolism was reinterpreted by the Soviet authorities. The three stars were said to stand for the three Baltic "republics" of the USSR – Latvian SSR, Lithuanian SSR, and Estonian SSR – held aloft by "Mother Russia", and the monument was said to have been erected after World War II as a "sign of popular gratitude" toward the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for the "liberation" of the three countries.[7][15] In the middle of 1963, when the issue of demolition was raised again, it was decided that the destruction of a structure of such artistic and historic value, the building of which had been funded by donations of the residents of Latvia, would only cause deep indignation, which in turn would cause tension in society.[15] Over time the misinterpretation of symbolism also was toned down and by 1988 the monument was said, with somewhat more accuracy, to have been built to "celebrate the liberation from bondage of the autocracy of the tsar and German barons", although withholding the fact that the Bolshevik Red Army and the Red Latvian Riflemen were also adversaries in the Latvian War of Independence.[1][13]

Despite the Soviet government's efforts, on 14 June 1987, about 5,000 people rallied to commemorate the victims of Soviet deportations.[1] This event, organized by the human rights group Helsinki-86, was the first time after the Soviet occupation that the flower-laying ceremony took place, as the practice was banned by the Soviet authorities.[1][26] In response the Soviet government organized a bicycle race at the monument at the time when the ceremony was planned to take place. Helsinki-86 organized another flower-laying ceremony on August 23 in the same year to commemorate the anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, at which the crowd was dispersed using jets of water.[27] Yet the independence movement grew in size, amounting in some events to more than half a million participants (about one quarter of Latvia's population) and three years later, on 4 May 1990, the re-establishment of the independence of Latvia was declared.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Since the re-establishment of independence the monument has become a focal point for a variety of events. One of these – on March 16, the commemoration day of veterans of the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS, who fought the Soviet Union during World War II – has caused controversy.[29] The date was first celebrated by Latvians in exile before being brought to Latvia in 1990 and for a short time (1998–2000) was the official remembrance day.[29][30] In 1998 the event drew the attention of the foreign mass media and in the following year the Russian government condemned the event as a "glorification of Nazism".[31] The event evolved into a political conflict between Latvians and Russians, posing a threat to public safety.[17][32]

The Latvian government took a number of steps in order to try to bring the situation under control, and in 2006 not only were the events planned by right wing organizations not approved, but the monument was fenced off, according to an announcement by Riga city council, for restoration.[17][33] The monument was indeed restored in 2006, but this statement was later questioned, as politicians named various other reasons for the change of date, the enclosed area was much larger than needed for restoration, and the weather appeared inappropriate for restoration work.[34] Therefore, the government was criticized by the Latvian press for being unable to ensure public safety and freedom of speech. The unapproved events took place despite the ban.[33] On November 23, 2006, the law requiring the approval of the authorities for public gatherings was ruled unconstitutional.[35] In the future years the government mobilized the police force to guard the neighborhood of the monument and the events were relatively peaceful.[36][37]

See also

Notes

- ↑ pronounced [ˈbriːviːbas ˈpiɛmineklis]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 (in Latvian) "Latvijas Enciklopēdija" (I sējums) Rīga 2002 SIA "Valērija Belokoņa izdevniecība" ISBN 9984-9482-1-8

- ↑ Kalnins, Ojars (August 16, 2001). "More than just a monument". The Baltic Times.

- ↑ Juozaitis, Arvydas (November 22, 2011). "Tėvynė ir Laisvė" (in Lithuanian). Alkas.lt.

- ↑ ARVĪDS JOZAITIS, Rīga - cita civilizācija (Ryga - niekieno civilizacija)

- ↑ Rudzīte, Arita (November 19, 2015). "Brīvības piemineklis – sadzīvisku sīkumu un nozīmīgu notikumu liecinieks jau 80 gadus" (in Latvian). aprinkis.lv.

- 1 2 http://www.vecriga.info/, retrieved on 2007-05-30

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brīvības Piemineklis, by Jānis Siliņš, Riga : Brīvības Pieminekļa Komitejas Izdevums (The Freedom Monument Committee), 1935, retrieved on 2007-02-07

- 1 2 Statue of Liberty, retrieved: 2007-02-07

- 1 2 3 New Materials for Conservation of Stone Monuments in Latvia Archived 2006-10-18 at the Wayback Machine by Inese Sidraba, Centre for Conservation and Restoration of Stone Materials, Institute of Silicate Materials, Riga Technical University

- ↑ (in Latvian) Iecere atvērt Brīvības pieminekļa iekštelpu Tvnet.lv (LNT) 2008-02-20, retrieved on 2008-02-20

- ↑ (in Latvian) Rīga 1860–1917 Rīga 1978 Zinātne (No ISBN)

- ↑ (in Latvian) Map at rigatourism.com Archived 2007-06-23 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 2007-06-03

- 1 2 (in Latvian) Enciklopēdija "Rīga" Rīga 1988 Galvenā enciklopēdiju redakcija (No ISBN)

- ↑ (in Latvian) "Laimas" pulkstenim veiks kosmētisko remontu Archived 2007-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 2007-04-20

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 (in Latvian) Brīvības pieminekli uzspridzināt, Pēteri I vietā ... Archived 2007-08-22 at the Wayback Machine Apollo.lv (Latvijas Avīze) 2006-05-05, retrieved on 2007-02-17

- 1 2 3 Environmental Influences on Cultural Heritage of Latvia Archived 2006-10-17 at the Wayback Machine by G. Mezinskis, L. Krage & M. Dzenis, Faculty of Materials Science and Applied Chemistry, Riga Technical University

- 1 2 3 (in Latvian) Brīvības pieminekļa atjaunošanas darbus sāks pirmdien Delfi.lv (Leta) 2006-03-10, retrieved on 2007-05-11

- ↑ (in Latvian) Brīvības pieminekļa atklāšanā skanēs Zigmara Liepiņa kantāte Delfi.lv (BNS) 2001-06-21, retrieved on 2007-02-15

- ↑ (in Latvian) Apzeltī bez garantijas Vietas.lv (Neatkarīga) 2006-04-20, retrieved on 2007-05-11

- ↑ "Kas noticis ar Brīvības pieminekļa Lāčplēsi?" (in Latvian). tvnet. 11 June 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- 1 2 (in Latvian) Bruņoto spēku seja Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Dialogi.lv 2004-11-17, retrieved: 2007-03-09

- 1 2 3 (in Latvian) Brīvības simbola sargs staburags.lv 2004-11-15, retrieved: 2007-03-09

- 1 2 3 4 (in Latvian) Dienests kā atbildīgs un interesants darbs bdaugava.lv 2006-11-16, retrieved: 2007-03-09

- ↑ (in Latvian) Godasardze pie Brīvības pieminekļa veiks ceremoniālu patrulēšanu apollo.lv (BBI) 2004-09-20, retrieved 2007-03-09

- ↑ "rigacase.com". Archived from the original on 2007-06-03. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ↑ George Bush: NATO will defend freedom worldwide Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Regnum News Agency, 2006-11-29, retrieved: 2007-02-07

- ↑ (in Latvian) "Helsinki – 86" rīkotās akcijas 1987. gadā Archived 2007-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved: 2007-03-19

- ↑ (in Latvian) Lūzums. No milicijas līdz policijai by Jānis Vahers, Ilona Bērziņa Nordik, 2006 ISBN 9984-792-16-1 "Lasītava". Archived from the original on 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- 1 2 (in Latvian) 16. marts Latviešu leģiona vēstures kontekstā by Antonijs Zunda, professor of Latvian University Archived 2007-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 2006-03-16

- ↑ (in Latvian) Law "On holidays and remembrance days" with amendments, retrieved: 2007-05-10

- ↑ "Appeal of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of Russian Federation 'To the members of the Saeima of the Republic of Latvia in connection with the organisation in Riga of the march of the veterans of the Latvian legion of SS', N 3788-II GD". pravo.gov.ru (in Russian). March 18, 1999. Retrieved March 16, 2006.

- ↑ (in Latvian) Provokācija pie Brīvības pieminekļa Archived 2007-03-17 at the Wayback Machine Archived press coverage regarding 2005-03-16 (Neatkarīgā; Diena; Latvijas Avīze), retrieved on 2007-05-10

- 1 2 (in Latvian) Latvijas jaunāko laiku vēsturē ierakstīta jauna 16. marta lappuse Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Archived press coverage regarding 2006-03-16 (Neatkarīgā; Diena; Latvijas Vēstnesis; Latvijas Avīze; Nedēļa), retrieved on 2007-03-17

- ↑ (in Latvian) Brīvības pieminekļa koka mētelītis Politika.lv 2006-03-14, retrieved 2007-03-18

- ↑ "Constitutional Court's judgment in case 2006-03-0106" (PDF). Constitutional Court of the Republic of Latvia. November 23, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ↑ (in Latvian) Policija Rīgas centrā gatavojas 16.marta pasākumiem Delfi.lv 2007-03-16, retrieved: 2007-03-19

- ↑ (in Latvian) Leģionāru piemiņas pasākums noritējis bez starpgadījumiem Delfi.lv 2008-03-16, retrieved: 2008-03-16