Joaquim da Silva Rabelo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 August 1779 |

| Died | 13 January 1825 (aged 45) Recife, Empire of Brazil |

Frei Joaquim do Amor Divino Rabelo, the religious name of Joaquim da Silva Rabelo (August 20, 1779 – January 13, 1825),[1] commonly known as Frei Caneca (English: Friar Mug), was a Brazilian religious leader, politician, and journalist. He was involved in multiple revolts in Northeastern Brazil during the early 19th century.[2] He acted as the main leader on the Pernambuco Revolt. As a journalist, he founded and edited Typhis Pernambucano, a weekly journal used on the Confederation of the Equator.

Evaldo Cabral de Mello described him as: "The man in the history of Brazil that embodied the quintessential nativist sentiment was curiously a Lusitanian 'jus sanguinis'."

Early life

Frei Caneca was the oldest son of Portuguese parents. His father, Domingos da Silva Rabelo, was a cooper from whom he got his nickname. His mother, Francisca Maria Alexandrina de Siqueira, was the cousin of a Carmelite nun. The family resided in Recife, more precisely in Fora-de-Portas, today known as Comunidade do Pilar, built during the Dutch Brazil era.

He became a novice at the Carmo and took the Religious habit in 1796 and professed the next year.

Career

He was ordained into the Carmelite Order in 1801, with the necessary apostolic dispensation of age 22, and created the Seminário de Olinda. He was authorized to attend the courses that the Order had not offered. He attended the seminary and oratorians libraries in Recife. In 1803 he was designated to teach rhetoric and geometry at his convent. Later he taught rational and moral philosophy.

At some point, "his interest goes beyond the walls of the cloister, as indicated by its provision in public chair geometry of Alagoas region". It remained there a short time, given the prospect of appointment to the same chair in Recife, which failed to materialize by the Pernambuco Revolt of 1817.

Caneca shared liberal and republican ideas, and attended the Academia do Paraíso, one of the meeting places of those who, influenced by the American and French revolutions, conspired against Portuguese rule.

Participation in revolts

.jpg.webp)

Movement in Pernambuco and prison in Bahia

Caneca's first foray into political life was during the Pernambuco Revolt when Pernambuco and other nearby provinces rebelled against the Portuguese royal court, which had relocated to Brazil during the Peninsular War. They felt that the government was ignoring the sugar-producing north in favor of the coffee-producing south, which was closer to the capital Rio de Janeiro.[3]

The revolt proclaimed a Republic and organized the first independent government in the region. No reference to his participation survived: "In the opening events of sedition on March 6, as the formation of the provisional government. Thus it is that the list of voters who chose him, not in his name. His presence only detects the last weeks of existence of the regime, to monitor the republican army, which marched to the south of the province, in order to face the troops of the Count of Arcos, at which, according to the indictment, would have exercised captain of guerrillas." He was the adviser to Republican South Army, which was commanded by colonel Suassuna.

After the rebellion was put down, he was imprisoned in Salvador for four years. During that time, he dedicated himself to the drafting of the Portuguese Grammar.

Return to Pernambuco

Pardoned[4] in 1821, in the context of the constitutionalist movement in Portugal, Frei Caneca returned to Pernambuco and resumed political activities. During his trip, he came to be held in a gaol of Campina Grande. In 1821 he was involved in the so-called movement of Goiana, a second emancipationist movement that proclaimed adherence to the Lisbon Cortes with the support of the main owners of the north woods and cotton provincial support. An army of rural militias and frontline troops marched against Recife, without occupying the city. The goianistas failed to find substantial support in the southern forest. The "Beberibe Convention" consecrated in September the status quo, predicting that Recife and Goiana would continue to operate in the areas under their control, pending the decision of the Courts. These determined the election of a provisional board that became the first self-government of the province in October 1821.

The governing board of Gervásio Pires

Frei Caneca supported the formation of the first Board of Governors of Pernambuco, chaired by a trader, Gervásio Pires Ferreira, who appointed him to the public chair of geometry in Recife. It was a very Recifean board, where the power came from the clergy, the urban strata, trade, the armed forces and the liberal professions – the defeated forces in 1817. Gervásio was the dominant figure of a government that wanted consensus. He was the leader of a Portuguese trade sector that was already nationalized by residence, by birth, and by family ties to the land.

In 1822 Frei Caneca, who enthusiastically supported the Board, wrote the "Dissertation on what is meant by country citizen and duties to this with the same country". He wanted to give theoretical formulation to one of the main objectives of Gervásio, which was to reconcile the Portuguese trade in the province with the new order. His main thesis was that the Portuguese domiciled in the ground and connected to it by family ties and interests should be considered as Pernambuco's main interest.

Evaldo Cabral de Mello stated, "The Cortes of Lisbon, on one hand, and the regency of Dom Pedro, on the other, embodied in terms of 1817 aspirations, equally legitimate options, although incomplete and contradictory. On one hand, the Sovereign Congress offered a liberal regime, under a constitutional monarchy, though, from February 1822, was clear in Brazil that they would charge the price of not pure and simple restoration of the commercial monopoly, it was impossible to resurrect but a preferential system for trade and Portuguese navigation. In turn, the regency of Rio promised freedom of trade and independence but with the expected bill of building an authoritarian regime based in south-central (region of Brazil)."

The government of Gervásio tried to gain time, waiting for a situation that would protect both options without entirely ruling out the separation from both Lisbon and Rio. The Board will be anathematized Varnhagen Jose Honorio Rodrigues, accused of lack of national feeling, their defense was made by Barbosa Lima Sobrinho).

Under the pressure of a military riot, the joint Gervásio Pires Ferreira was coerced to join the cause of Rio de Janeiro and ended up deposed by a military uprising, forming a so-called "Yokels Government" in October 1822.

The Board of Yokels

On September 23, 1822, the so-called "Board of Yokels" was elected, which replaced the Gervasiana Board. This government lasted until December 1823. It was dominated by representatives of large landed property. elected members of the Board were President Afonso de Albuquerque Maranhao, Secretary Jose Mariano de Albuquerque and members Francisco Pais Barreto, squire Cape; Francisco de Paula Gomes dos Santos, Manuel Inacio Bezerra de Melo, Francisco de Paula Cavalcanti de Albuquerque and João Nepomuceno Carneiro da Cunha.

This led Frei Caneca to join the fray. His polemic with José Fernandes Gama and his nephew, Judge Bernardo José da Gama, conspiracy leaders criticized Gervásio, writing "Pythia Letters to Daman". 'Pedrosada' was a failed attempt to overthrow the Board of Yokels. Afterwards, the Gamas tried to recover in court and denounced what they called the Republican faction of the province, drawing up a list of suspects that included Frei Caneca.

Brother Mug sided with the opposition without fighting it, but he preferred to engage against the group in Rio de Janeiro, which intended to dictate the fate of the province. Frei Caneca even pronounced a gratitude prayer on the occasion of the thanksgiving ceremony in the Church of the Holy Body, by Pedro I acclamation as emperor. Only from the constitution of Manuel de Carvalho Pais de Andrade government that seven months after the inauguration proclaim the Confederation of Ecuador, there were signs of close collaboration of Frei Caneca with power, but also in the form of journalistic activity and, sporadically, giving his opinion on some of the big decisions that the government should take.

The first of his letters went out March 17, 1823, shortly after the 'Pedrosada'. It was published in the Mail of Rio de Janeiro, a periodical property of João Soares Lisboa, who participated in the Confederation of the Equator, and died on September 30, 1824, wounded in combat during his escape through the interior of Pernambuco next to Brother Mug and other companions. Pedro da Silva Pedroso, or Pedrosa, was the governor of arms of the province that retraced the Pais Barreto alliance that toppled Gervásio, without which could depose him, for his support of Gama, in court.

Frei Caneca never fought the Board of Yokels. He preferred to focus on the Pernambuco faction of the Court, endorsing the personnel policy of the emperor, be it under Jose Bonifácio, or under his successors.

As for the Pedrosada, the established wanton that pronounced Pedrosa and Paula Gomes and José Fernandes Gama members of the government, and due to the imperial protection none of them were to be punished. Divided and demoralized, the Board of Yokels dragged a sad resistance until December 1823 when he resigned. Faced by the opposition of the old gervasistas around the mayor of Manuel de Carvalho Andrade, Navy Parent, and Cipriano Barata, who had returned from Lisbon Cortes; and the pressures of Rio de Janeiro, which required Pernambuco monthly amounts of the king's time and further two million, equivalent to shipments to Portugal after the departure of the king.

The Confederation of the Equator

He and others soon grew frustrated with the constitution of the newly formed Empire of Brazil,[5][6] which limited autonomy in the provinces, and returned to secessionist politics, this time becoming a leader in the Confederation of the Equator by providing much of its intellectual support.[5][7] In addition, he published Typhis Pernambucano, a pro-Confederation newspaper critical of Pedro I and the imperial government from 1823 to 1824.[8]

It is essential to know the political and provincial context of Brother Mug political works, the situation in which they lived Pernambuco and the other provinces to understand the movement that represented the Confederation of Ecuador - muffled under "the weight of Saquarema's tradition in Brazilian historiography Independence", that is, which Evaldo Cabral de Mello called "the historiography of Rio de Janeiro state court and its epigones in the Republic" claiming for the three great provinces of the Southeast the role of builders of nationality. The revolutionary Pernambuco cycle cannot, of course, be considered separatists – but the presumption of separatism was the result of the gap occurred between the emancipation process in the Southeast and Northeast. In Rio, says Cabral de Mello, "The Independence began as a dispute between absolutists and liberals around the United Kingdom of Portugal organization and even then not cogitated separation Portugal, only to preserve the status acquired by Brazil within the Lusitanian empire. The situation was very different in the Northeast, where independence has started with a dispute between colony and metropolis, with the difference that the latter was no longer in Lisbon but in Rio de Janeiro ..."

In 1823 during the movement known as 'Pedrosada', Brother Mug I wrote "The Hunter" and "Pythia Letters to Daman". Says Cabral de Mello, page 29 of the cited work: "In the euphoria that followed the liberal revolution of the Kingdom, the expectations of reducing the burden of taxes in trade and agriculture were not lower than the rest of Brazil. They were perhaps larger, since the installation of the court in 1808, Pernambuco was burdened with new taxes for including the public lighting of Rio, promptly revoked by Gervásio's Board. ... The state of bankruptcy that had reduced Banco do Brasil with the return of King John VI and the establishment of provincial boards had severely limited the action of the Court, which had only the customs resources and province of Rio de Janeiro time the other provinces also denied resources. Thus, the north accession to the emperor was above all a matter of urgent financial, coffee not as profitable at the mid-30s, so the main line of the tax revenue which had to come from sugar and cotton, products predominantly northerners."

He took part with Cipriano Barata, as one of the leaders in the Ecuadorian Confederation, republican and separatist movement. His arguments are not directed against the emperor but against what he considered the authoritarian drift of Jose Bonifacio. After September 7, "the intensification of the fight between Jose Bonifacio and the liberals of the Court had led to censorship of the press, with the closure of newspapers and the attack on the director of the Malagueta, and the arrest of more than 300 individuals, the same who had beaten for independence since the departure of John VI". There were other dissatisfaction reasons: requirements of Rio de Janeiro state treasury, the draft constitution published by the Correio Brasiliense in September 1822, the creation of the Swiss battalion, the foundation of the Apostolate, the institution of Imperial Cruise Order, seen as "the club of servile aristocrats".

Evaldo Cabral de Mello believes it would be more appropriate instead of Pernambuco republicanism, consider itself autonomous."The Revolution project was ancient in Pernambuco" later comment on the judge of Appeals that dismissed the motion. There was "a reinterpretation of provincial history in the light of revolutionary modernity represented by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution". For Brother Mug and the Autonomous Party, punished by Republican failure in 1817, "the provincial autonomy had priority over the form of government". They would be ready to enter into a commitment to the Rio, which in exchange for acceptance of the monarchical regime, would give ample relief to provinces. There would be no reason to reject the monarchy, since authentically constitutional and since preserved the franchises. Reading the newspaper, Cipriano Barata, "The Sentinel of Liberty", denied the charges of republicanism.

In 1824 Frei Caneca became one of the advisers of Manuel de Carvalho Pais de Andrade, opining against recognizing Francisco Pais Barreto, the squire of the Cabo, as president of Pernambuco. He opined the Alagoas invasion, in order to eradicate the counter-revolutionary forces squire of Cabo; and against the oath of the Constitution bestowed by D. Pedro I. Says Evaldo Cabral de Mello that "Brother Mug underestimated the means at the disposal of Rio Court, overestimating the other hand, the local will of resistance to Rio's despotism."

D. Pedro I suspended constitutional guarantees in the province, punishing it territorially, amputating the district of San Francisco, on which was the left bank of the river San Francisco, now incorporated into the territory of Bahia. Recife underwent naval blockade, this time by Admiral Cochrane, who bombarded the city. Pernambuco was invaded from the south by the troops of Brigadier Lima e Silva. Since the sugarcane owners in the south woods remained neutral, his troops easily occupied Recife on September 12, 1824.

Again defeated, he took refuge with a part of his troops in the countryside and fled north towards Ceará. During this flight, he started writing the "Route".

The Typhis Pernambucano

On December 25, 1823, circulated the first issue of "Typhis Pernambucano" newspaper that would be the trench of Brother Mug until the settlement of the Confederacy. It states that is considered guilty of the situation of the Portuguese party in Rio and the ministry had happened to José Bonifácio. The dissolution of the Assembly took Pernambuco by surprise but "from July 2 onwards the history of Confederation became the narrative of defeat."

Prison and death

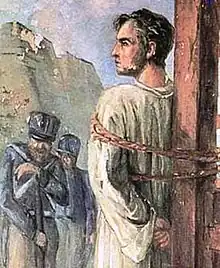

After the defeat of the Confederation, he was arrested by imperial troops on November 29[9] for his participation as Secretary of the armed rebellion and also as its spiritual director. He was incarcerated in Recife. On December 18, 1824, there was established a military commission under the chairmanship of Colonel Francisco de Lima e Silva (father of the future Duke of Caxias) to conduct the trial on the charges of sedition and rebellion against the imperial orders of his Imperial majesty. With full power to judge and condemn summarily, the accused was sentenced to death by hanging. The convict himself described his trial:

On the 20th, I was brought before the assassin court of commission, whose members were General Francisco de Lima e Silva, president, judge-rapporteur, Thomas Xavier Garcia de Almeida, and other members, Colonel engineering Salvador Jose Maciel, the Lieutenant Colonel hunters Francisco Vicente Souto, Colonel hunters Manuel Antonio Leitao Flag, the Earl of Escragnolle, that was my questioner.[10]

On December 18 he was tried by a military commission, found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging. In court documents, Frei Caneca was indicted as one of the rebellion's leaders and for writing incendiary papers. The two other leaders were Stinho Bezerra Cavalcanti, captain of grenadiers and commander of the 4th Battalion Gunners Henriques, and Francisco de Souza Rangel.

Altogether the execution involved eleven confederates, including three in Rio de Janeiro. The first was Brother Mug, who charged with sedition and rebellion.

On January 13, 1825, was set up the hanging of the show before the walls of the Fort of Five Points. Stripped of religious habit, i.e. "without the orders in the Rosary church, the sacred canons form" still having three executioners who refused to hang him. The Military Commission ordered his death by firing squad ("since it can not be hanged for disobedience of the executioners"),[1][2] attached to one of the gallows rods, by a platoon under the command of the same official. His body was placed near one of the gates of the Carmelite church in the center of Recife, being collected by religious and buried in place until now unidentified.

The wall against which the cleric was shot, next to the Five Points Fort, still stands. The site is marked by a bust and an allusive plaque placed by the Archaeological Institute, History and Geography Pernambucano in 1917. The iconography of Brother Mug, the best-known work is the public "Execution Frei Caneca", by Murillo La Greca.

In culture

The poet and writer João Cabral de Melo Neto described in verses, in 1984, the last day of Frei Caneca, in his work The Friar's Way (Auto do Frade).[11] His brother, the historian Evaldo Cabral de Mello, was the organizer and wrote the introduction to the book "Frei Joaquim do Amor Divino Caneca Coleção Formadores do Brasil", Editora 34, Ltda, 2001 entitled "Brother Mug or Another Independence" (Frei Caneca ou an Outra Independência). As for the other players, says Evaldo Cabral de Mello, Manuel de Carvalho took refuge on board an English frigate, going to live in London, where only return after the abdication to restart a political career that would take him to the presidency of Pernambuco and Senate Empire. The poet Natividade Saldanha, secretary of the Board, is sought asylum in Venezuela and then in Bogota, where he practiced law and died in 1830.

See also

Citations

- 1 2 "Frei Caneca - Biografia - UOL Educação". Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- 1 2 Homero do Rêgo Barros, Frei Caneca: herói e mártir republicano (1983), 8 pages

- ↑ "Revolução Pernambucana de 1817 - Brasil Escola". Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ↑ Nossa História. Year 3 issue 35. São Paulo: Vera Cruz, 2006, p.44

- 1 2 Enciclopédia Barsa. Volume 5: Camarão, Rep. Unida do – Contravenção. Rio de Janeiro: Encyclopædia Britannica do Brasil, 1987, p.464

- ↑ Vainfas, Ronaldo. Dicionário do Brasil Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2002, p.161

- ↑ Dohlnikoff, Miriam. Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX. São Paulo: Globo, 2005, p.56

- ↑ "Empire of Exceptions: The Making of Modern Brazil". History Today. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ↑ Lustosa, Isabel. D. Pedro I. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007, p. 176

- ↑ "Itinerário", in: Frei Joaquim do Amor Divino Caneca. Coleção Formadores do Brasil, 1994. p. 604. A mesma obra reproduz os autos do processo (pp. 607 ff.).

- ↑ Süssekind, Flora. Stepping Into Prose, World Literature Today, vol.33 no.4 (autumn 1992.) JSTOR.