The French Restoration style was predominantly Neoclassicism, though it also showed the beginnings of Romanticism in music and literature. The term describes the arts, architecture, and decorative arts of the Bourbon Restoration period (1814–1830), during the reign of Louis XVIII and Charles X from the fall of Napoleon to the July Revolution of 1830 and the beginning of the reign of Louis-Philippe.

Architecture and design

Public buildings and monuments

La Madeleine, changed from a temple of glory to Napoleon's army back to a church–

La Madeleine, changed from a temple of glory to Napoleon's army back to a church– The Chapelle expiatoire by Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1826)

The Chapelle expiatoire by Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1826) Mass in the Chapelle expiatoire designed by Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine

Mass in the Chapelle expiatoire designed by Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine Old Paris Bourse, or stock market (1826)

Old Paris Bourse, or stock market (1826)

To commemorate the memory of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette and to expiate the crime of their execution, King Louis XVIII built the Chapelle expiatoire by Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine on the site of the small cemetery of the Madeleine, where their remains (now in the Basilica of Saint-Denis) had been hastily buried following their execution. It was completed and dedicated in 1826.

The royal government restored the symbols of the old regime, but continued the construction of most of the monuments and urban projects begun by Napoleon. The church of La Madeleine, begun under Louis XVI, had been turned by Napoleon into the Temple of Glory (1807). It was now turned back to its original purpose, as the Royal church of La Madeleine. All of the public buildings and churches of the Restoration were built in a relentlessly neoclassical style. Work resumed, slowly, on the unfinished Arc de Triomphe, begun by Napoleon. At the end of the reign of Louis XVIII, the government decided to transform it from a monument to the victories of Napoleon into a monument celebrating the victory of the Duke of Angôuleme over the Spanish revolutionaries who had overthrown their Bourbon king. A new inscription was planned: "To the Army of the Pyrenees" but the inscription had not been carved and the work was still not finished when the regime was toppled in 1830. [1]

The Canal Saint-Martin was finished in 1822, and the building of the Bourse de Paris, or stock market, designed and begun by Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart from 1808 to 1813, was modified and completed by Éloi Labarre in 1826. New storehouses for grain near the Arsenal, new slaughterhouses, and new markets were finished. Three new suspension bridges were built over the Seine; the Pont d'Archeveché, the Pont des Invalides and footbridge of the Grève. All three were rebuilt later in the century.

Religious architecture

The church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1823–36) by Louis-Hippolyte Lebas;

The church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1823–36) by Louis-Hippolyte Lebas; The church of Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle (1828–30), by Étienne-Hippolyte Godde

The church of Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle (1828–30), by Étienne-Hippolyte Godde Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (1824–44) by Jacques Ignace Hittorff

Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (1824–44) by Jacques Ignace Hittorff

Several new churches were begun during the Restoration to replace those destroyed during the Revolution. A battle took place between architects who wanted a neo-Gothic style, modeled after Notre-Dame, or the Neoclassical style, modeled after the basilicas of ancient Rome. The battle was won by a majority of neoclassicists on the Commission of Public Buildings, who dominated until 1850. Jean Chalgrin had designed Saint-Philippe de Role before the Revolution in a neoclassical style; it was completed (1823–30) by Étienne-Hippolyte Godde. Godde also completed Chalgrin's project for Saint-Pierre-du-Gros-Caillou {1822–29), and built the neoclassic basilicas of Notre-Dame-du-Bonne Nouvelle ((1823–30) and Saint-Denys-du-Saint-Sacrament (1826–35). [2] Other notable neoclassical architects of the Restoration included Louis-Hippolyte Lebas, who built Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1823–36); (1823–30); and Jacques Ignace Hittorff, who built the church of Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (1824–44). Hittorff went on to along a brilliant career in the reigns of Louis Philippe and Napoleon III, designing the new plan of the Place de la Concorde and constructing the Gare du Nord railway station (1861–66). [3]

Commercial architecture - the shopping gallery

A new form of commercial architecture had appeared at the end of the 18th century; the passage, or shopping gallery, a row of shops along a narrow street covered by a glass roof. They were made possible by improved technologies of glass and cast iron, and were popular since few Paris streets had sidewalks and pedestrians had to compete with wagons, carts, animals and crowds of people. The first indoor shopping gallery in Paris had opened at the Palais-Royal in 1786; rows of shops, along with cafes and the first restaurants, were located under the arcade around the garden. It was followed by the passage Feydau in 1790–91, the passage du Caire in 1799, and the Passage des Panoramas in 1800.[4] In 1834 the architect Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine carried the idea a step further, covering an entire courtyard of the Palais-Royal, the Galerie d'Orleans, with a glass skylight. The gallery remained covered until 1935. It was the ancestor of the glass skylights of the Paris department stores of the later 19th century. [5]

Residential architecture

During the Restoration, and particularly after the coronation of King Charles X in 1824. New residential neighborhoods were built on the Right Bank in Paris, as the city grew to the north and west. Between 1824 and 1826, a time of economic prosperity, the quarters of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Europe, Beaugrenelle and Passy were all laid out and construction began. The width of lots grew larger; from six to eight meters wide for a single house to between twelve and twenty meters for a residential building. The typical new residential building was four to five stories high, with an attic roof sloping forty-five degrees, broken by five to seven windows. The decoration was largely adapted from that of the Rue de Rivoli; horizontal rather than vertical orders, and simpler decoration. The windows were larger and occupied a larger portion of the façades. Decoration was provided by ornamental iron shutters and then wrought-iron balconies. Variations of this model were the standard on Paris boulevards until the Second Empire.[6]

The hôtel particular, or large private house of the Restoration, usually was built in a neoclassical style, based on Greek architecture or the style of Palladio, particularly in the new residential quarters of Nouvelle Athenes and the Square d'Orleans on Rue Taibout (9th arrondissement), a private residential square (1829–35) in the English neoclassical style designed by Edward Cresy. Residents of the square included George Sand and Frédéric Chopin. Some of the houses in the new quarters in the 8th arrondissement, particularly the quarter of François I, begun in 1822, were made in a more picturesque style, a combination of the Renaissance and classical style, called the Troubadour style. This marked the beginning of the movement away from uniform neoclassicism toward eclectic residential architecture.[6]

Interior Design and Furniture

Decoration of the Chateau de Dampierre

Decoration of the Chateau de Dampierre Musée Charles X, Salle 2, at the Louvre

Musée Charles X, Salle 2, at the Louvre.jpg.webp) Decoration of the Musée Charles X, the Louvre

Decoration of the Musée Charles X, the Louvre.jpg.webp) Decoration in the Musée Charles X, the Louvre

Decoration in the Musée Charles X, the Louvre.jpg.webp) Cabinet of Auguste Comte, with Voltaire armchair and gondola chairs

Cabinet of Auguste Comte, with Voltaire armchair and gondola chairs The Voltaire armchair, a popular form introduced during the Restoration

The Voltaire armchair, a popular form introduced during the Restoration

The decorative style of the French Restoration borrowed from both the geometry of the neoclassical style era, and the overload of decoration of the Louis XIV style, along with the color of Renaissance. One of the best examples is the Charles X museum within the Louvre, a suite of rooms that was created for, among other purposes, the Salon of artists that was held there annually. The ceilings were divided into compartments filled with paintings and lavishly decorated with corniches, columns and pilasters. The neo-Gothic also began to appear in interior decoration during the 1820, particularly in the design of galleries and salons with arches and arched windows and rose windows modeled after those in gothic cathedrals. Another feature of the French restoration was polychromy, the use of bright colors in the decorations, either with colored stone, glass, or paintings. Ceilings were particularly lavish, with hemicycles, cupolas, pendants, and vaults, often filled with decorative paintings. [7]

Another good example of the French Restoration style of design is the interior of the Chapelle expiatoire. While the layout of the building and architecture is sober and perfectly Greco-Roman neoclassicism, the inside of the dome is decorated with rosettes, and there is an abundance of high-relief sculpted decoration in bands below the cornices and between the columns supporting the dome, including stylized Maltese crosses, fleur-de-lis and roses. The floor also has elaborate polychrome decoration in stone with the same motifs. [8]

With the downfall of Napoleon, those aristocrats who had fled France during the Revolution began to return; they found their furniture had largely been confiscated and sold during the Revolution, and they had little money to buy lavish new furniture. The new King, Louis XVIII, liked the Empire style, so that style remained in place, with slightly rounded lines, and the removal of the Napoleonic symbols and ornaments,[9] After the death of Louis XVIII in 1824, the new King, his brother Charles X, allotted an indemnity to aristocrats whose belongings had been confiscated during the Revolution, and the luxury furniture industry began to revive. Interest began to develop in older styles, particularly Gothic and Renaissance, especially after the creation of a museum of French monuments during the Revolution, but the gothic revival movement did not become really strong until after the publication in 1831 of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo (1831).[10]

Ornament of gilded bronze became rarer; most ornament was marquetry inlay, either light wood into dark, or dark wood into light; often in form of very elaborate floral designs, under the influence of the Duchesse de Berry. Under Charles X, the á la Cathédral or Cathedral chair became popular, with a back resembling the form of a Gothic stained glass window.[11] The Gothic rose also became a popular decoration on furniture, along with stylized palmettes and other floral designs. Comfort was another consideration in the design of new chairs. The Voltaire armchair, with sabre-curved front legs, a high curving padded back and padded armrests, became popular.[12] It took its name from a popular illustration of portrait of Voltaire, made about 1820, which showed him seated in s similar armchair.[13]

Painting

The Grand Odalisque by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1814)

The Grand Odalisque by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1814) Coronation of Charles X of France by François Gérard (c. 1827) Fine Arts Museum of Chartres

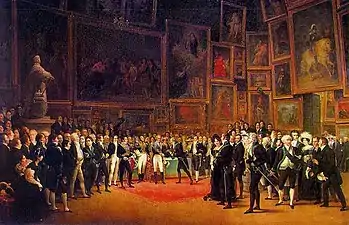

Coronation of Charles X of France by François Gérard (c. 1827) Fine Arts Museum of Chartres Charles X presents awards to artists at the 1824 Salon in the Louvre, by François Joseph Heim

Charles X presents awards to artists at the 1824 Salon in the Louvre, by François Joseph Heim.jpg.webp) The Raft of the Medusa by Jean Louis Théodore Géricault (1818–1819), the Louvre

The Raft of the Medusa by Jean Louis Théodore Géricault (1818–1819), the Louvre Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix (1830), the Louvre

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix (1830), the Louvre

The Restoration saw the beginning of the long battle between neoclassicism and romanticism in painting and other domains of art. Jacques-Louis David, the dominant neoclassical painter during the reign of Napoleon, went into exile in Belgium; however, other prominent students of David remained in Paris, and continued the style, simply changing the subject matter. They included François Gérard, who painted the coronation of King Charles X in 1827, following almost exactly the composition used by David in his coronation painting of the Emperor Napoleon.[14] Other former pupils of David included Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), and the most prominent of all, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, (1780-1867), who painted his famous Grand Odalisque in the year that Napoleon first went into exile.[15]

The new generation of neoclassicists, led by Ingres and Gérard, largely ignored the idea of a classicism based on Ancient Roman and Greek values, and concentrated instead on the perfection of the depiction of human body, by its lines, composition and color.[16] During the Restoration, Ingres was commissioned to paint a mural for the ceiling of the Salle Clarac of the Louvre, called Apothéose de Homer. Completed in 1827, it brought together all of the famous artists of history, attending the crowning of Homer by an angel. Ingres also surpassed all of his contemporaries of the period as a portrait painter. In 1819 Ingres painted Roger rescuing Angelique, inspired by St. George slaying a dragon, in an almost surrealistic setting. Here Ingres' style foreshadowed the drama of Gustave Moreau Other painters who often followed the more delicate and sensual version of neoclassicism included Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1758–1821), and the portraitist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.[17]

An entirely different approach to painting was taken by Jean Louis Théodore Géricault with his painting The Raft of the Meduse (1818–1819), depicting the true story of the survivors of a shipwreck, gathered on a raft, appealing for help to a far distant ship. Géricault had meticulously studied anatomy to make the dead bodies on the raft more realistic. The painting was bitterly attacked by many critics and defended by many others, including the poet Baudelaire and the painter Horace Vernet. Géricault returned to the theme in 1821-24, with "The Tempest" or "The shipwreck" a painting of a corpse washed ashore on beach during storm. (1821–24), illustrating graphically again how humans were powerless against nature. In 1822–23, Gericault painted La Folle, a portrait of a madwoman in a Paris asylum with a distant, hopeless stare. His school of painting became known a "theatrical romanticism".[18]

Eugène Delacroix was another major painter of "theatrical romanticism" who emerged during the Restoration. As a young painter, he was particularly impressed by the works of Rubens in the Louvre, by the drawings of Goya, and the paintings of Constable. After traveling to England, where he met Constable, he returned to Paris and became friends with Stendhal, Balzac and Victor Hugo. At the Paris Salon of 1827, he showed nine paintings. The following year, he presented The Death of Sardanapale. In the fall of 1830, shortly after the July Revolution, which toppled King Charles X, he painted Liberty Leading the People, which was presented at the 1831 Salon, and became one of the icons of French art.[19]

Sculpture

Peace riding a chariot, atop Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel by FrançoisJoseph Bosio (1828)

Peace riding a chariot, atop Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel by FrançoisJoseph Bosio (1828) Hyacinth, by François Joseph Bosio (1817) Louvre

Hyacinth, by François Joseph Bosio (1817) Louvre Hercules fighting Acheloos transformed into a snake by François Joseph Bosio (1826) Louvre

Hercules fighting Acheloos transformed into a snake by François Joseph Bosio (1826) Louvre Louis XVI by François Joseph Bosio

Louis XVI by François Joseph Bosio.jpg.webp) Equestrian statue of Louis XIV in Place des Victoires

Equestrian statue of Louis XIV in Place des Victoires Bust of the Marquis de Lafayette by David d'Angers (1828)

Bust of the Marquis de Lafayette by David d'Angers (1828)

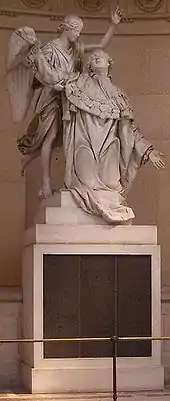

The most prominent French sculptor of the Restoration was François Joseph Bosio (1768-1845). Born in Monaco, he received a scholarship from the Prince of Monaco to study in Paris, under Augustin Pajou. During the Empire of Napoleon, he sculpted some of the plaques on the column in Place Vendôme, and made numerous portrait busts of the Emperor's family. During the restoration, he became the royal sculptor to the King, and made both portrait busts and sculptors in the classical-romantic style. He made the central statue Louis XVI for the Expiatory Chapel, called Apotheosis of Louis XVI or Louis XVI called to immortality, supported by an angel. In 1828 he completed a new work of sculpture for the top of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel at the Louvre. A chariot and horse sculpture, taken by Napoleon from St Mark's Basilica in Venice, had originally been placed atop the arch, but it had been returned to Venice after Napoleon's downfall. The Bourbons commissioned Bosio to make a new work, Peace guiding a Chariot, to commemorate the Bourbon Restoration. Bosio was also commissioned to replace the equestrian statue of Louis XIV which had been the centerpiece of Place des Victoires, which had been destroyed during the Revolution. His new version, twelve meters high, was installed in 1828.

Another notable French sculptor of the period was Pierre Jean David 1788–1856), who called himself David d'Angers, to distinguish himself from his teacher, Jacques Louis David. He worked in the studio of Jacques Louis David beginning in 1809. Then, between 1811 and 1816 he studied at the French Academy in Rome, where he became familiar with the works of Canova, the great Italian master of romanticism. However, he turned his own work toward classicism, illustrating the patriotic and moral virtues. He made busts or statues of many notable statesmen, including the Marquis de Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson and Goethe. In 1830, he began working on his best-known work, the frieze over the entrance of the Pantheon, titled The Country recognizes its great men, which he completed in 1837. [20]

Another notable sculptor who began his career during the Restoration was François Rude, (1784–1847), He moved to Paris from Dijon in 1805 to study with Pierre Cartellier. In 1811 he won the Prix de Rome, but he was a confirmed Bonapartist, and after the downfall of Napoleon, he went into exile in Belgium, where he had success as a portrait sculptor. He did not return until 1827. Between 1833 and 1836, he made the celebrated sculptures, called Les Marseillaise, which decorate the Arc de Triomphe.

Literature and theater

Drawing of Honoré de Balzac in the 1820s

Drawing of Honoré de Balzac in the 1820s.png.webp) Alexandre Dumas by Achille Devéria (1829)

Alexandre Dumas by Achille Devéria (1829) Victor Hugo in 1829, by Achille Devéria (1829)

Victor Hugo in 1829, by Achille Devéria (1829)

The Bourbon restoration saw the rise of romanticism to the position of the dominant movement in French literature. The earliest prominent romantic was François-René de Chateaubriand, an essayist and diplomat. He began the Restoration as a committed defender of the Catholic faith and royalist, but gradually moved into the liberal opposition and became a fervent supporter of freedom of speech. Other prominent romantic writers of the period included the poet and politician Alphonse de Lamartine, Gérard de Nerval, Alfred de Musset, Théophile Gautier, and Prosper Mérimée.[21]

Despite limitations on press freedom, Paris editors published the first works of some of France's most famous writers. Honoré de Balzac moved to Paris in 1814, studied at the University of Paris, wrote his first play in 1820, and published his first novel, Les Chouans, in 1829. Alexandre Dumas moved to Paris in 1822, and found a position working for the future King, Louis-Philippe, at the Palais-Royal. In 1829, At the age of 27, he published his first play, Henri III and his Courts. Stendhal, a pioneer of literary realism, published his first novel, The Red and the Black, in 1830.[22]

The young Victor Hugo declared that he wanted to be "Chateaubriand or nothing". His first book of poems, published in 1822 when he was twenty years old, earned him a royal prize from Louis XVIII. His second book of poems in 1826 established him as one of France's leading poets. He wrote his first plays, Cromwell and Hernani in 1827 and 1830, and his first short novel, The Last Days of a Condemned Man, in 1829. The premiere of the ultra-romantic play Hernani caused a riot in the audience, on the eve of the fall of the Bourbon Monarchy,[23]

Music

The restoration of the monarchy with the coronation of Louis XVIII brought an end to the era of gigantic outdoor celebrations with patriotic music of the Revolution and the Empire of Napoleon. Instead, music returned to the salons of the old aristocracy, who returned from exile, and the new aristocracy created under Napoleon Bonaparte. The Music Conservatory in Paris was renamed the Royal School of Music, and the King commissioned the Italian-born Luigi Cherubini, newly named music director of the chapel of the Tuileries Palace, to write a requiem mass for Louis XVI, as well as a coronation mass for himself. The composer Gaspare Spontini was named director of royal music. A royal institution of religious music was also established in 1825, to perform early masterpieces of French religious music by Clément Janequin and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, which had been banned during the Revolution and ignored under Napoleon I.[24]

Carl Maria von Weber (1825)

Carl Maria von Weber (1825) Portrait of Luigi Cherubini by Ingres (1842)

Portrait of Luigi Cherubini by Ingres (1842) Set for The Siege of Corinth by Gioachino Rossini (1826)

Set for The Siege of Corinth by Gioachino Rossini (1826) Lithograph of Gioachino Rossini in 1829

Lithograph of Gioachino Rossini in 1829

The composers most performed in the part of the period were the work of composers of the pre-revolutionary period, Gluck, Sacchini and Spontini, but new composers soon appeared, including Carl Maria von Weber, who arrived from Germany, and staged a highly-successful French version of the first romantic German opera, Der Freischütz, or The Marksman, in 1824.[24]

The most successful musical theater of the period was the Théâtre-Italien, which performed in the Salle Favert in Paris; it produced the a series of operas by the most famous composer of the period, Gioachino Rossini, including The Barber of Seville in 1819. Rossini moved to Paris in 1824, and was named Director of Music and Staging at the Théâtre-Italien. Only Italian works were presented, always in Italian. Rossini became the most prominent figure of the Paris musical world, writing the music for the coronation of Charles X in 1824.

In 1820, a Bonapartist assassinated the Duke du Berry at the Paris opera house on rue de Richelieu. King Louis XVIII ordered the immediate closing, and then the demolition, of the Opera House. The Opera moved to the Salle Le Peletier, where it remained for fifty years. This theater was the scene of the birth of the first French grand opera, and the first romantic opera, with the premier of La Muette de Portici by Auber in July 1829. The theme of this opera, the rebellion of the people of Naples against Spanish rule, was particularly romantic and revolutionary. A performance of the opera in Brussels in 1830 led to riots, followed by a real revolution. Wagner attended a performance and wrote, "it was something entirely new; no one had seen a subject of an opera so current; it was the first true musical drama in five acts entirely provided with all the elements of tragedy, and notable also for its tragic ending."[24]

The Paris opera continued to astonish its audiences with new musical and visual effects. For the opera The Last Days of Pompeii by Giovanni Pacini, the opera employed the scientist and inventor Louis Daguerre to create optical illusions on a screen simulating dancing flames and the waves of the sea.[24]

To satisfy the demands of Paris opera-goers for truly grand opera, Rossini was commissioned to write the Le siège de Corinthe and then William Tell. This last work, which premiered at the Pelletier opera house on August 3, 1829, despite its famed overture, disappointed the critics, who criticized its excessive length, weak story, and lack of action. The criticism stung Rossini, and, at the age of thirty-seven, he retired from writing operas.[25]

The musical salons of the aristocracy had a working-class counterpart in Paris during the Restoration; the goguette, musical clubs formed by Paris workers, craftsmen, and employees. There were goguettes of both men and women. They usually met once a week, often in the back room of a cabaret, where they would enthusiastically sing popular, comic, and sentimental songs. During the Restoration, songs were also an important form of political expression. The poet and songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger became famous for his songs ridiculing the aristocracy, the established church and the ultra-conservative parliament. He was imprisoned twice for his songs, in 1821 and 1828, which only added to his fame. His supporters around France sent foie gras, fine cheeses and wines to him in prison. The celebrated Paris police chief Eugène François Vidocq sent his men to infiltrate the goguettes and arrest those who sang songs ridiculing the monarch.[26]

Notes and citations

- ↑ Héron de Villefosse 1959, p. 313.

- ↑ Texier 2012, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Sarmant 2012, p. 163.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, p. 36.

- ↑ Texier 2012, pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 Texier 2012, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 182.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 186.

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, pg. 96-97

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, pg. 96-97

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, (2006) pg. 98

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, (2006) pg. 98

- ↑ Storck, Justin, Le Dictionnaire pratique de menuiserie, ébénisterie, charpente,

- ↑ Toman, Neoclassicism et Romanticism (2007), page 377

- ↑ Toman, Neoclassicism et Romanticism (2007), page 377

- ↑ Toman, Neoclassicism et Romanticism (2007), page 382

- ↑ Toman, (2007), page 390–96

- ↑ Toman, (2007), page 411-412

- ↑ Toman, (2007), page 408-409

- ↑ Toman 2007, p. 298.

- ↑ Petit Larousse de l'histoire de France (2004), pages 361-364

- ↑ Petit Larousse de l'histoire de France (2004), pages 361-364

- ↑ Petit Larousse de l'histoire de France (2004), pages 361-364

- 1 2 3 4 Vila 2006, p. 126.

- ↑ Vila 2006, p. 133.

- ↑ Vila 2006, p. 128.

Bibliography

- De Morant, Henry (1970). Histoire des arts décoratifs. Librarie Hacahette.

- Droguet, Anne (2004). Les Styles Transition et Louis XVI. Les Editions de l'Amateur. ISBN 2-85917-406-0.

- Ducher, Robert (1988), Caractéristique des Styles, Paris: Flammarion, ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221--07862-4.

- Héron de Villefosse, René (1959). Histoire de Paris. Bernard Grasset.

- Prina, Francesca; Demartini, Elena (2006). Petite encylopédie de l'architecture. Paris: Solar. ISBN 2-263-04096-X.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Les styles en architecture. Dunod. ISBN 978-2-10-070689-1.

- Renault, Christophe (2006), Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, Paris: Gisserot, ISBN 978-2-877-4746-58

- Riley, Noël (2004), Grammaire des Arts Décoratifs de la Renaissance au Post-Modernisme, Flammarion, ISBN 978-2-080-1132-76

- Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-755-803303.

- Texier, Simon (2012), Paris- Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours, Paris: Parigramme, ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Toman, Rolf (2007). Neoclassicicsm et Romantisme- Architecture, Sculpture, Peinture, Dessin (in French). Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8331-3557-6.

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.

- Vila, Marie Christine (2006). Paris Musique- Huit Siècles d'histoire. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-419-3.