| African French | |

|---|---|

| français africain | |

Officine de pharmacie privée à Abidjan, route de Bassam | |

| Region | Africa |

Native speakers | 167 million (mostly non-native speakers) (2023)[1][2][3] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (French alphabet) French Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Countries and territories

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| IETF | fr-002 |

| |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| French language |

|---|

| History |

| Grammar |

| Orthography |

| Phonology |

|

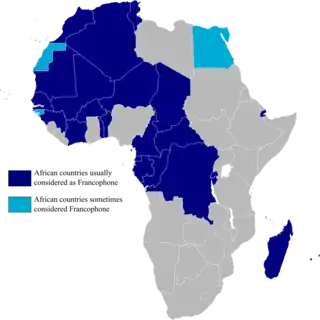

African French (French: français africain) is the generic name of the varieties of the French language spoken by an estimated 167 million people in Africa in 2023 or 51% of the French-speaking population of the world (mostly as a second language)[8][9][10] spread across 34 countries and territories.[Note 1] This includes those who speak French as a first or second language in these 34 African countries and territories (dark and light blue on the map), but it does not include French speakers living in other African countries. Africa is thus the continent with the most French speakers in the world.[11][12] French arrived in Africa as a colonial language; these African French speakers are now a large part of the Francophonie.

In Africa, French is often spoken alongside indigenous languages, but in a number of urban areas (in particular in Central Africa and in the ports located on the Gulf of Guinea) it has become a first language, such as in the region of Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire,[13] in the urban areas of Douala and Yaoundé in Cameroon or in Libreville, Gabon.

In some countries it is a first language among some classes of the population, such as in Tunisia, Morocco, Mauritania and Algeria, where French is a first language among the upper classes along with Arabic (many people in the upper classes are simultaneous bilinguals in Arabic/French), but only a second language among the general population.

In each of the francophone African countries, French is spoken with local variations in pronunciation and vocabulary.

List of countries in Africa by French proficiency

French proficiency in African countries according to the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF).[14][15]

| Countries | Total population | French speaking population | Percentage of the population that speaks French | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45,350,141 | 14,903,789 | 32.86% | 2022 | |

| 12,784,728 | 4,306,099 | 33.68% | 2022 | |

| 22,102,838 | 5,403,610 | 24.45% | 2022 | |

| 12,624,845 | 1,073,506 | 8.50% | 2022 | |

| 567,676 | 61,461 | 10.83% | 2022 | |

| 27,911,544 | 11,490,652 | 41.17% | 2022 | |

| 5,016,678 | 1,435,061 | 28.61% | 2022 | |

| 17,413,574 | 2,249,023 | 12.92% | 2022 | |

| 907,411 | 237,140 | 26.13% | 2022 | |

| 95,240,782 | 72,110,821 | 74%[16] | 2022 | |

| 5,797,801 | 3,518,464 | 60.69% | 2022 | |

| 27,742,301 | 9,324,605 | 33.61% | 2022 | |

| 1,016,098 | 508,049 | 50% | 2022 | |

| 106,156,692 | 3,204,706 | 3.02% | 2022 | |

| 1,496,673 | 432,705 | 28.91% | 2022 | |

| 2,331,532 | 1,865,225 | 80%[17] | 2023 | |

| 2,558,493 | 511,699 | 20.00% | 2022 | |

| 32,395,454 | 273,795 | 0.85% | 2022 | |

| 13,865,692 | 3,776,660 | 27.24% | 2022 | |

| 2,063,361 | 317,351 | 15.38% | 2022 | |

| 29,178,075 | 7,729,277 | 26.49% | 2022 | |

| 21,473,776 | 3,702,660 | 17.24% | 2022 | |

| 4,901,979 | 655,948 | 13.38% | 2022 | |

| 1,274,720 | 926,053 | 72.65% | 2022 | |

| 37,772,757 | 13,456,845 | 35.63% | 2022 | |

| 33,089,463 | 98,822 | 0.30% | 2022 | |

| 26,083,660 | 3,362,988 | 12.89% | 2022 | |

| 13,600,466 | 792,815 | 5.83% | 2022 | |

| 227,679 | 45,984 | 20.20% | 2022 | |

| 17,653,669 | 4,640,365 | 26.29% | 2022 | |

| 99,433 | 52,699 | 53.00% | 2022 | |

| 8,680,832 | 3,554,266 | 40.94% | 2022 | |

| 12,046,656 | 6,321,391 | 52.47% | 2022 |

Varieties

There are many different varieties of African French, but they can be broadly grouped into five categories:[18]

- the French spoken by people in West and Central Africa – spoken altogether by about 97 million people in 2018, as either a first or second language.[19]

- the French variety spoken by Maghrebis and Berbers in Northwest Africa (see Maghreb French), which has about 33 million first and second language speakers in 2018.[19]

- the French variety spoken in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, which has about 0.5 million first and second language speakers in 2018.[19]

- the French variety spoken by Creoles in the Indian Ocean (Réunion, Mauritius and Seychelles), which has around 1.75 million first and second language speakers in 2018.[19] The French spoken in this region is not to be confused with the French-based creole languages, which are also spoken in the area.

- the French varieties spoken in Eastern Africa (Madagascar, Comoros, Mayotte), which have 5.6 million first and second language speakers in 2018.[19]

All the African French varieties differ from standard French, both in terms of pronunciation and vocabulary, but the formal African French used in education, media and legal documents is based on standard French vocabulary.

_Chez_Maman_la_Joie.jpg.webp)

In the colonial period, a vernacular form of creole French known as Petit nègre ("little negro") was also present in West Africa. The term has since, however, become a pejorative term for "poorly spoken" African French.

The difficulty linguists have in describing African French comes from variations, such as the "pure" language used by many African intellectuals and writers versus the mixtures between French and African languages. For this, the term "creolization" is used, often in a pejorative way, and especially in the areas where French is on the same level with one or more local languages. According to Gabriel Manessy, "The consequences of this concurrency may vary according to the social status of the speakers, to their occupations, to their degree of acculturation and thus to the level of their French knowledge."[20]

Code-switching, or the alternation of languages within a single conversation, takes place in both Senegal and Democratic Republic of Congo, the latter having four "national" languages – Kikongo, Lingala, Ciluba and Swahili – which are in a permanent opposition to French. Code-switching has been studied since colonial times by different institutions of linguistics. One of these, located in Dakar, Senegal, already spoke of the creolization of French in 1968, naming the result "franlof": a mix of French and Wolof (the language most spoken in Senegal) which spreads by its use in urban areas and through schools, where teachers often speak Wolof in the classroom despite official instructions.[21]

The omnipresence of local languages in francophone African countries – along with insufficiencies in education – has given birth to a new linguistic concept: le petit français.[20] Le petit français is the result of a superposition of the structure of a local language with a narrowed lexical knowledge of French. The specific structures, though very different, are juxtaposed, marking the beginning of the creolization process.

Français populaire africain

In the urban areas of francophone Africa, another type of French has emerged: Français populaire africain ("Popular African French") or FPA. It is used in the entirety of sub-Saharan Africa, but especially in cities such as Abidjan, Ivory Coast; Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; Dakar, Senegal; Cotonou, Benin; and Lomé, Togo. At its emergence, it was marginalized and associated with the ghetto; Angèle Bassolé-Ouedraogo describes the reaction of the scholars:

Administration and professors do not want to hear that funny-sounding and barbarian language that seems to despise articles and distorts the sense of words. They see in it a harmful influence to the mastery of good French.[22]

However, FPA has begun to emerge as a second language among the upper class. It has also become a symbol of social acceptance.

FPA can be seen as a progressive evolution of Ivorian French. After diffusing out of Ivory Coast, it became Africanized under the influence of young Africans (often students) and cinema, drama, and dance.

FPA has its own grammatical rules and lexicon. For example, "Il ou elle peut me tuer!" or "Il ou elle peut me dja!" can either mean "This person annoys me very much (literally he or she is annoying me to death)" or "I'm dying (out of love) for him/her" depending on the circumstances. "Il ou elle commence à me plaire" signifies a feeling of exasperation (whereupon it actually means "he or she starts to appeal to me"), and friendship can be expressed with "c'est mon môgô sûr" or "c'est mon bramôgo."[22]

FPA is mainly composed of metaphors and images taken from African languages. For example, the upper social class is called "les en-haut d'en-haut" (the above from above) or "les môgôs puissants" (the powerful môgôs).

Pronunciation

Pronunciation in the many varieties of African French can be quite varied. There are nonetheless some trends among African French speakers; for instance, ⟨r⟩ tends to be pronounced as the historic alveolar trill of pre-20th Century French instead of the now standard uvular trill or 'guttural R.' The voiced velar fricative, the sound represented by ⟨غ⟩ in the Arabic word مغرب Maghrib, is another common alternative. Pronunciation of the letters ⟨d⟩, ⟨t⟩, ⟨l⟩ and ⟨l⟩ may also vary, and intonation may differ from standard French.

Abidjan French

According to some estimates, French is spoken by 75 to 99 percent of Abidjan's population,[23] either alone or alongside indigenous African languages. There are three sorts of French spoken in Abidjan. A formal French is spoken by the educated classes. Most of the population, however, speaks a colloquial form of French known as français de Treichville (after a working-class district of Abidjan) or français de Moussa (after a character in chronicles published by the magazine Ivoire Dimanche which are written in this colloquial Abidjan French). Finally, an Abidjan French slang called Nouchi has evolved from an ethnically neutral lingua franca among uneducated youth into a creole language with a distinct grammar.[24] New words often appear in Nouchi and then make their way into colloquial Abidjan French after some time.[25] As of 2012, a crowdsourced dictionary of Nouchi is being written using mobile phones.[26]

Here are some examples of words used in the African French variety spoken in Abidjan (the spelling used here conforms to French orthography, except ô which is pronounced [ɔ]):[27]

- une go is a slang word meaning a girl or a girlfriend. It is a loanword either from the Mandinka language or from English ("girl"). It is also French hip-hop slang for a girl.[28]

- un maquis is a colloquial word meaning a street-side eatery, a working-class restaurant serving African food. This word exists in standard French, but its meaning is "maquis shrubland", and by extension "guerrilla", see Maquis (World War II). It is not known exactly how this word came to mean street-side restaurant in Côte d'Ivoire.

- un bra-môgô is a slang word equivalent to "bloke" or "dude" in English. It is a loanword from the Mandinka language.

- chicotter is a word meaning to whip, to beat, or to chastise (children). It is a loanword from Portuguese where it meant "to whip (the black slaves)". It has now entered the formal language of the educated classes.

- le pia is a slang word meaning money. It comes perhaps from the standard French word pièce ("coin") or pierre ("stone"), or perhaps piastre (dollar, buck).

When speaking in a formal context, or when meeting French speakers from outside Côte d'Ivoire, Abidjan speakers would replace these local words with the French standard words une fille, un restaurant or une cantine, un copain, battre and l'argent respectively. Note that some local words are used across several African countries. For example, chicotter is attested not only in Côte d'Ivoire but also in Senegal, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad, the Central African Republic, Benin, Togo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[25]

As already mentioned, these local words range from slang to formal usage, and their use therefore varies depending on the context. In Abidjan, this is how the sentence "The girl stole my money." is constructed depending on the register:[25]

- formal Abidjan French of the educated people: La fille m'a subtilisé mon argent.

- colloquial Abidjan French (français de Moussa): Fille-là a prend mon l'argent. (in standard French, the grammatically correct sentence should be Cette fille (là) m'a pris de l'argent)

- Abidjan French slang (Nouchi): La go a momo mon pia. (Momo is an Abidjan slang word meaning "to steal")

Another unique, identifiable feature of Ivorian French is the use of the phrase n'avoir qu'à + infinitif which, translated into English, roughly means, to have only to + infinitive.[29] The phrase is often used in linguistic contexts of expressing a wish or creating hypotheticals. This original Ivorian phrase is generally used across the Ivory Coast's population; children, uneducated adults, and educated adults all using the phrase relatively equally. Often in written speech, the phrase is written as Ils non cas essayer de voir rather than Ils n'ont qu'à essayer de voir.[29]

Linguistic Characteristics

Many linguistic characteristics of Ivorian/Abidjan French differ from "standard" French found in France. Many of these linguistic evolutions are due to the influences of native African languages spoken within the Ivory Coast, making Abidjan French a distinct dialect of French.

Some of the major phonetic and phonological variations of Abidjan French, as compared to a more "typical" French, include substituting the nasal low vowel [ɑ̃] for a non-nasal [a], especially when the sound occurs at the beginning of a word as well as some difficulty with the full production of the phonemes [ʒ] and [ʃ].[30] There also exists, to a certain degree, rhythmic speaking speaking patterns in Ivorian French that are influenced by native languages.[30]

Ivorian French is also unique in its grammatical differences present in spoken speech. Some of these grammatical changes include:[30]

- omission of articles in some contexts (ex. tu veux poisson instead of the French tu veux du poisson)

- omission of prepositions in some contexts (ex. Il parti Yamoussoukro rather than Il est parti à Yamoussoukro)

- interchangeable usage of indirect & direct complements (using lui instead of le and vice versa)

- more flexible grammatical formation

Algerian French

Without being an official language, French is frequently used in government, workplaces, and education. French is the default language for work in several sectors. In a 2007 study set in the city of Mostaganem, it was shown that French and Arabic are the two functional languages of banking. Technical work (accounting, financial analysis, management) is also frequently done in French. Documents, forms, and posters are often in both French and Arabic.

The usage of French among the Algerian population is different depending on social situations. One can find:

- direct borrowings, where the lexical unit is unchanged: surtout (particularly), voiture (car)

- integrated borrowings, where the lexical unit experiences phonetic transformation: gendarme (police force), cinéma (cinema)

- code switching, where another language is spoken in addition to French in a single oration (ex: Berber/French, Arabic/French)

Beninese French

French is the only official language in Benin.

In 2014, over 4 million Beninese citizens spoke French (around 40% of the population). Fongbe is the other widely-spoken language of Benin. It is natural to hear both languages blending, either through loan words or code switching.

Few academic sources exist surrounding the particularisms of Beninese French. Nevertheless, it's evident that Beninese French has adapted the meanings of several French terms over time, such as: seconder (to have relations with a second woman, from the French second - second), doigter (to show the way, from the French doigt - finger).

Egyptian French

French is not an official language in Egypt. Nevertheless, it is widely taught. The city of Alexandria is home to the French-speaking Senghor University. For the majority of Egyptian French-speakers, French is neither a native nor a second language.

Egyptian French is notably impacted by Egyptian Arabic. Examples include:

- el-triangle (instead of le triangle, or "the triangle")

- tab, w-el-hauteur ? (instead of bon, et la hauteur ?, or "okay, and the height?")

- akhtar masan les deux plus petits côtés (instead of je choisis les deux plus petits côtés, or "I choose the two smallest sides")

In French sentences, the determinant is frequently either expressed in Arabic or omitted altogether. It is imagined that this is the result of the education-centric nature of French in Egypt; the goal for students learning French is expressing their ideas, not correctly constructing sentences. These particularities are sometimes compared to a Creole.

Kinshasa French

With more than 11 million inhabitants, Kinshasa is the largest francophone city in the world, recently passing Paris in population. It is the capital of the most populous francophone country in the world, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where an estimated 43 million people (51% of the total population) can speak French (essentially as a second language).[19][31] Contrary to Abidjan where French is the first language of a large part of the population, in Kinshasa French is only a second language, and its status of lingua franca is shared with Lingala. Kinshasa French also differs from other African French variants, for it has some Belgian French influences, due to colonization. People of different African mother tongues living in Kinshasa usually speak Lingala to communicate with each other in the street, but French is the language of businesses, administrations, schools, newspapers and televisions. French is also the predominant written language.

Due to its widespread presence in Kinshasa, French has become a local language with its own pronunciation and some local words borrowed for the most part from Lingala. Depending on their social status, some people may mix French and Lingala, or code switch between the two depending on the context. Here are examples of words particular to Kinshasa French. As in Abidjan, there exist various registers and the most educated people may frown upon the use of slangish/Lingala terms.

- cadavéré means broken, worn out, exhausted, or dead. It is a neologism on the standard French word cadavre whose meaning in standard French is "corpse". The word cadavéré has now spread to other African countries due to the popularity of Congolese music in Africa.

- makasi means strong, resistant. It is a loanword from Lingala.

- anti-nuit are sunglasses worn by partiers at night. It is a word coined locally and whose literal meaning in standard French is "anti-night". It is one of the many Kinshasa slang words related to nightlife and partying. A reveler is known locally as un ambianceur, from standard French ambiance which means atmosphere.

- casser le bic, literally "to break the Bic", means to stop going to school. Bic is colloquially used to refer to a ballpoint pen in Belgian French and Kinshasa French, but not in standard French.

- merci mingi means "thank you very much". It comes from standard French merci ("thank you") and Lingala mingi ("a lot").

- un zibolateur is a bottle opener. It comes from the Lingala verb kozibola which means "to open something that is blocked up or bottled", to which was added the standard French suffix -ateur.

- un tétanos is a rickety old taxi. In standard French tétanos means "tetanus".

- moyen tê vraiment means "absolutely impossible". It comes from moyen tê ("there's no way"), itself made up of standard French moyen ("way") and Lingala tê ("not", "no"), to which was added standard French vraiment ("really").

- avoir un bureau means to have a mistress. Il a deux bureaux doesn't mean "He has two offices", but "He has two mistresses".

- article 15 means "fend for yourself" or "find what you need by yourself".

- ça ne dérange pas means "thank you" or "you are welcome". When it means "thank you", it can offend some French speakers who are not aware of its special meaning in Kinshasa. For example, if one offers a present to a person, they will often reply ça ne dérange pas. In standard French, it means "I don't mind".

- quatre-vingt-et-un is the way Kinois say 81, quatre-vingt-un in Europe.

- compliquer quelqu'un, literally to make things "complicated" or difficult for someone. It can be anyone: Elle me complique, "She is giving me a tough time".

- une tracasserie is something someone does to make another person's life harder, and often refers to policemen or soldiers. A fine is often called a tracasserie, especially because the policemen in Kinshasa usually ask for an unpayable sum of money that requires extensive bargaining.

Linguistic Characteristics

There are many linguistic differences that occur in Kinshasa French that make it a distinct dialect of French. Similarly to many other African dialects of French, many of these linguistic aspects are influenced, either directly or indirectly, by the linguistics of the local African languages spoken. It is also essential to note grammatical differences between local Congolese languages and the French language, such as the lack of gendered nouns in the former, which result in linguistic changes when speakers of Congolese native languages speak French.[32]

Some of the phonetic characteristics of Kinshasa French include:[33]

- the posteriorization of anterior, labial vowels in French, more specifically, the posteriorization of the common French phoneme [ɥ] for [u] (ex. pronunciation of the French word cuisine [kɥizin] as couwisine [kuwizin])

- the delabialization of the phoneme [y] for the phoneme [i] (ex. pronunciation of the French term bureau [byʁo] as biro [biʁo])

- the vocalic opening of the French phoneme [œ] creating, instead, the phoneme [ɛ] (ex. pronunciation of the French word acteur [aktœʁ] as actère [aktɛʁ])

- in some cases, the denasalization of French vowels (ex. pronunciation of the French term bande [bɑ̃d] as ba-nde [band])

- the mid-nasalization of occlusive consonants that follow the nasals [n] and [m] (ex. in relationship to the example above, the French word bande [bɑ̃d] could be pronounced both as ba-nde [band] or as ban-nde with a slightly nasalized [d])

- the palatalization of French apico-dental consonants that are followed by [i] and/or [ɥ] (ex. pronunciation of the French word dix [dis] is pronounced as dzix [dzis] and, similarly, the term parti may be pronounced as partsi)

As briefly mentioned above, because many Congolese languages are ungendered languages, there is often some mixing of the French masculine and feminine articles in speakers of Kinshasa French, such as the phrase Je veux du banane rather than the "correct" French Je veux de la banane.[32]

See also

- French colonial empire

- Belgian colonial empire

- Geographical distribution of French speakers

- Camfranglais

- List of colonies and possessions of France

- Belgian Congo

- Maghreb French

- Françafrique

- Francophonie

- French-based creole languages

- French language in Minnesota

- French language in Vietnam

- French language in Cambodia

- French language in Laos

- French Polynesia

- Languages of Africa

Notes

- ↑ 29 full members of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF): Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, DR Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Niger, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Seychelles, Togo, and Tunisia.

One associate member of the OIF: Ghana.

One observer of the OIF: Mozambique.

One country not member or observer of the OIF: Algeria.

Two French territories in Africa: Réunion and Mayotte.

References

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Accueil-Francoscope

- ↑ Population Reference Bureau. "2020 World Population Data Sheet - Population mid-2020". Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Population Reference Bureau. "2020 World Population Data Sheet - Population mid-2050". Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Accueil-Francoscope

- ↑ Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF). "La langue française dans le monde" (PDF) (2019 ed.). p. 38. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ↑ Chutel, Lynsey (18 October 2018). "French is now the fifth most spoken world language and growing—thanks to Africans". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ↑ (in French) Le français à Abidjan : Pour une approche syntaxique du non-standard by Katja Ploog, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2002

- ↑ Richard Marcoux; Laurent Richard; Alexandre Wolff (March 2022). "observatoire.francophonie.org" (PDF). ODSEF. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ↑ "Qui parle français dans le monde – Organisation internationale de la Francophonie – Langue française et diversité linguistique".

- ↑ "target-survey-french-most-spoken-language-drc".

- ↑ "What Languages Are Spoken In Gabon?".

- ↑ "Is there a difference between French and African French?". African Language Solutions. 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Observatoire de la langue française de l’Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. "Estimation du nombre de francophones (2018)" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- 1 2 Manessy, Gabriel (1978). "Le français d'Afrique noire, français créole ou créole français ?" [The French of black Africa: French creole or creole French?]. Langue française (in French). 37 (1): 91–105. doi:10.3406/lfr.1978.4853. JSTOR 41557837.

- ↑ Calvet, Maurice jean; Dumont, Pierre (1969). "Le français au Sénégal : interférences du wolof dans le français des élèves sénégalais" [The French of Senegal: Wolof interference in the French of Senegalese students]. Collection IDERIC (in French). 7 (1): 71–90.

- 1 2 Bassolé-Ouedraogo, A (2007). "Le français et le français populaire africain: partenariat, cohabitation ou défiance? FPA, appartenance sociale, diversité linguistique" (PDF) (in French). Institut d'Études des Femmes, Université d'Ottawa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27.

- ↑ Marita Jabet, Lund University. "La situation multilinguistique d'Abidjan" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ Sande, Hannah (2015). "Nouchi as a Distinct Language: The Morphological Evidence" (PDF). In Kramer, Ruth; Zsiga, Elizabeth C.; Tlale Boyer, One (eds.). Selected Proceedings of the 44th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. pp. 243–253.

- 1 2 3 Bertin Mel Gnamba and Jérémie Kouadio N'Guessan. "Variétés lexicales du français en Côte d'Ivoire" (PDF) (in French). p. 65. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- ↑ "Languages: Crowd-Sourced Online Nouchi Dictionary". Rising Voices. 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ Suzanne Lafage (2002). "Le lexique français de Côte d'Ivoire" (in French). Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ "Le Dictionnaire de la Zone © Cobra le Cynique".

- 1 2 Johnson, Manda Djoa (2011). "La locution verbale n'avoir qu'à + infinitif dans le français ivoirien/La locución verbal francesa n'avoir qu'à + infinitivo en el francés marfileño" [The verbal phrase to have only with + infinitive in Ivorian French]. Thélème (in French). 26: 79–88. Gale A383852945 ProQuest 1017876369.

- 1 2 3 Baghana, Jerome; Glebova, Yana A.; Voloshina, Tatiana G.; Blazhevich, Yuliya S.; Birova, Jana (14 June 2022). "Analyzing the effect of interference on the utilization of French in ivory coast: social and linguistic aspects". Revista de Investigaciones Universidad del Quindío. 34 (S2): 13–19. doi:10.33975/riuq.vol34nS2.873. S2CID 249701668.

- ↑ Observatoire démographique et statistique de l'espace francophone (ODSEF). "Estimation des populations francophones dans le monde en 2018 - Sources et démarches méthodologiques" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- 1 2 Baghana, Jerome; Voloshina, Tatiana G.; Slobodova Novakova, Katarina (2019). "Morphological and syntactic interference in the context of Franco-Congolese bilingualism". XLinguae. 12 (3): 240–248. doi:10.18355/XL.2019.12.03.18. S2CID 199175583.

- ↑ Gombé-Apondza, Guy-Roger Cyriac (2015). "Particularités phonétiques du français dans la presse audio-visuelle de Kinshasa" [The French Phonetic particularities in the broadcast media in Kinshasa] (PDF). Synergies Afrique des Grands Lacs. 4: 101–116. ProQuest 2060963904.

External links

- LE FRANÇAIS EN AFRIQUE - Revue du Réseau des Observatoires du Français Contemporain en Afrique(in French)

- Links for Afrique francophone

- Dictionaries of various French-speaking countries

- Le Français et le Français populaire Africain: partenariat, cohabitation ou défiance? FPA, appartenance sociale, diversité linguistique (in French)

- La mondialisation, une chance pour la francophonie (in French)

- RFI - L’avenir du français passe par l’Afrique (in French)