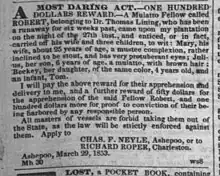

Fugitive slave advertisements in the United States, or runaway slave ads, were paid classified advertisements describing a missing person and usually offering a monetary reward for the recovery of the valuable chattel. Fugitive slave ads were a unique vernacular genre of non-fiction specific to the antebellum United States. These ads often include detailed biographical information about individual enslaved Americans including "physical and distinctive features, literacy level, specialized skills,"[1] and "if they might have been headed for another plantation where they had family, or if they took their children with them when they ran."[2]

Runaway slave ads sometimes mentioned local slave traders who had sold the slave to their owner,[3] and were occasionally placed by slave traders who had suffered a jailbreak.[4] Some ads had implied or explicit threats against "slave stealers," be they altruistic abolitionists like the "nest of infernal Quakers"[5] in Pennsylvania, or criminal kidnappers.

Harriet Beecher Stowe devoted a chapter of A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin to examining fugitive slave ads, writing "Every one of these slaves has a history, a history of woe and crime, degradation, endurance, and wrong."[6] She noted that such ads typically include descriptions of color and complexion, perceived intelligence of the slave, and scars or a clause to the effect of "no scars recollected."[6] Stowe also observed the irony of these ads appearing in newspapers with mottos like Sic semper tyrannis and "Resistance to tyrants is obedience to god."[6]

American Baptist, Dec. 20, 1852: TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD FOR A PREACHER. The following paragraph, headed "Twenty Dollars Reward," appeared in a recent number of the New Orleans Picayune: "Runaway from the plantation of the undersigned the negro man Shedrick, a preacher, 5 feet 9 inches high, about 40 years old, but looking not over 23, stumped N. E. on the breast, and having both small toes cut of. He is of a very dark complexion, with eyes small but bright, and a look quite insolent. He dresses good, and was arrested as a runaway at Donaldsonville, some three years ago. The above reward will be paid for his arrest, by addressing Messrs. Armant Brothers, St. James parish, or A. Miltenberger & Co., 30 Carondelet street." Here is a preacher who is branded on the breast and has both toes cut off—and will look insolent yet! There's depravity for you!

— Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1853

Ads describing self-emancipated slaves are a valuable primary source on the history of slavery in the United States and have been used to study the material life,[7] multilinguality,[8] and demographics of enslaved people.[9] Books by 19th-century abolitionist Theodore Weld had a "polemical effect" that was "achieved by his documentary style: a deceptively straightforward litany of fugitive slave advertisements, many of them gruesome in the details of physical abuse and mutilation."[10] Freedom on the Move is a crowdsourced archive of runaway slave ads published in the United States.[11]

Three U.S. Presidents, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson are known to have placed runaway slave ads, seeking to recapture fugitives Oney Judge, Sandy,[12] and in the case of Jackson, both "a mulatto Man Slave" in 1804, and Gilbert in 1822.[13]

Thomas Jefferson and slavery: "Run away from the subscriber..." (Virginia Gazette, 1769)

Thomas Jefferson and slavery: "Run away from the subscriber..." (Virginia Gazette, 1769).jpg.webp) George Washington and slavery: "Absconded from the household of the President of the United States..." (Pennsylvania Gazette, May 24, 1796)

George Washington and slavery: "Absconded from the household of the President of the United States..." (Pennsylvania Gazette, May 24, 1796)

See also

References

- ↑ Thomas, Heather. "Research Guides: Fugitive Slave Ads: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction". guides.loc.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ Lewis, Danny. "An Archive of Fugitive Slave Ads Sheds New Light on Lost Histories". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ "$25 Reward". The Weekly Advertiser. 1856-06-18. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ↑ "$30 Reward". The Tennessean. 1855-05-15. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ↑ "The Last of His Kind: Talk with an Old Slave-Seller Who Lags Superfluous on the Stage". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1884-05-24. p. 12. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- 1 2 3 Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). "Chapter IX: Slaves as They Are, on Testimony of Owners". A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.

- ↑ Hunt-Hurst, Patricia (1999). ""Round Homespun Coat & Pantaloons of the Same": Slave Clothing as Reflected in Fugitive Slave Advertisements in Antebellum Georgia". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 83 (4): 727–740. ISSN 0016-8297.

- ↑ Foy, Charles R. (2006). "Seeking Freedom in the Atlantic World, 1713—1783". Early American Studies. 4 (1): 46–77. ISSN 1543-4273.

- ↑ Jones, Kelly Houston (2012). ""A Rough, Saucy Set of Hands to Manage": Slave Resistance in Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 71 (1): 1–21. ISSN 0004-1823.

- ↑ Oakes, James (1986). "The Political Significance of Slave Resistance". History Workshop (22): 89–107. ISSN 0309-2984.

- ↑ "Freedom on the Move: Rediscovering the Stories of Self-Liberating People". Zinn Education Project. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ↑ Costa, Tom (2001). "What Can We Learn from a Digital Database of Runaway Slave Advertisements?". International Social Science Review. 76 (1/2): 36–43. ISSN 0278-2308.

- ↑ Hay, Robert P. (1977). ""And Ten Dollars Extra, for Every Hundred Lashes Any Person Will Give Him, to the Amount of Three Hundred": A Note on Andrew Jackson's Runaway Slave Ad of 1804 and on the Historian's Use of Evidence". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 36 (4): 468–478. ISSN 0040-3261.

Further reading

- Schafer, Judith Kelleher (February 1981). "New Orleans Slavery in 1850 as Seen in Advertisements". The Journal of Southern History. 47 (1): 33. doi:10.2307/2207055.