Gilan province

استان گیلان | |

|---|---|

| |

Location of Gilan province in Iran | |

| Coordinates: 37°26′N 49°33′E / 37.433°N 49.550°E | |

| Country | Iran |

| Region | Region 3 |

| Capital | Rasht |

| Counties | 17 |

| Government | |

| • Governor-general | Asadollah Abbasi |

| • MPs of Assembly of Experts | 1 Ahmad Parvaei Rik 2 Reza Ramezani Gilani 3 Seyed Ali Hosseini Ashkevari 4 Zaynolabideen Ghorbani |

| • Representative of the Supreme Leader | Rasool Falahati |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14,042 km2 (5,422 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,530,696 |

| • Density | 180/km2 (470/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+03:30 (IRST) |

| Area code | 013 |

| ISO 3166 code | IR-01 |

| Main language(s) | Gilaki Talyshi |

| HDI (2017) | 0.805[2] very high · 11th |

| Others(s) | Persian[3] Azeri[4][5][6][7][8][9] |

| Website | www |

Gilan Province (Persian: استان گیلان, Ostān-e Gīlan)[10] is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It lies along the Caspian Sea, in Iran's Region 3, west of the province of Mazandaran, east of the province of Ardabil, and north of the provinces of Zanjan and Qazvin.[11] It borders Azerbaijan (Astara District) in the north.

The northern section of the province is part of the territory of South (Iranian) Talysh. At the center of the province is the city of Rasht, the capital of Gilan. Other cities include Astaneh-ye Ashrafiyeh, Astara, Fuman, Hashtpar, Lahijan, Langarud, Masuleh, Manjil, Rudbar, Rudsar, Shaft, Siahkal, and Sowme'eh Sara. The main port is Bandar-e Anzali, formerly known as Bandar-e Pahlavi.

At the 2006 census, the province was home to 2,381,063 people in 669,221 households.[12] The following census in 2011 counted 2,480,874 in 777,316 households.[13] By the time the latest census was conducted in 2016, the population of Gilan had risen to 2,530,696 people in 851,382 households.[1]

History

Paleolithic

Early humans were present at Gilan since Lower Paleolithic. Darband Cave is the earliest known human habitation site in Gilan province; it is located in a deep tributary canyon of the Siah Varud and contains evidence for the earliest prehistoric human cave occupation during the Lower Paleolithic in Iran.

Stone artifacts and animal fossils were discovered by a group of Iranian archaeologists that dates back to the late Chibanian.[14] Yarshalman is a Middle Paleolithic shelter that was probably occupied by Neanderthals about 40,000 to 70,000 years ago.[14] Later Paleolithic sites in Gilan are Chapalak Cave[15] and Khalvasht shelter.[16]

Early history

It seems that the Gelae, or Gilites, entered the region south of the Caspian coast and west of the Amardos River (now called the Sefid-Rud) in the second or first century BCE, Pliny identifies them with the Cadusii who were living there previously. It is more likely that they were a separate people, had come from the region of Dagestan, and taken the place of the Kadusii. That the native inhabitants of Gilan have some originating roots in the Caucasus is supported by genetics and language, as the Y-DNA of Gilaks most closely resemble that of Georgians and other South Caucasus peoples, while their mtDNA closely resembles other Iranian groups.[17] Their languages shares typologic features with the languages of the Caucasus.[18]

Medieval history

Gilan province was the place of origin of the Ziyarid dynasty and Buyid dynasty in the mid-10th century. Previously, the people of the province had a prominent position during the Sassanid dynasty through the 7th century, so that their political power extended to Mesopotamia.

The first recorded encounter between Gilak and Deylamite warlords and invading Muslim armies was at the Battle of Jalula in 637 AD. Deylamite commander Muta led an army of Gils, Deylamites, Persians and people of the Rey region. Muta was killed in the battle, and his defeated army managed to retreat in an orderly manner.

However, this appears to have been a Pyrrhic victory for the Arabs, since they did not pursue their opponents. Muslim Arabs never managed to conquer Gilan as they did with other provinces in Iran. Gilanis and Deylamites successfully repulsed all Arab attempts to occupy their land or to convert them to Islam.

In fact, it was the Deylamites under the Buyid king Mu'izz al-Dawla who finally shifted the balance of power by conquering Baghdad in 945. Mu'izz al-Dawla, however, allowed the Abbasid caliphs to remain in comfortable, secluded captivity in their palaces.[19]

The Church of the East began evangelizing Gilan in the 780s, when a metropolitan bishopric was established under Shubhalishoʿ.[20] In the 9th and 10th centuries AD, Deylamites and later Gilanis gradually converted to Zaydi Shiʿism.

Several Deylamite commanders and soldiers of fortune who were active in the military theaters of Iran and Mesopotamia were openly Zoroastrian (for example, Asfar Shiruyeh a warlord in central Iran, and Makan, son of Kaki, the warlord of Rey) or were suspected of harboring pro-Zoroastrian (for example Mardavij) sentiments. Muslim chronicles of Varangian (Rus', pre-Russian Norsemen) invasions of the littoral Caspian region in the 9th century record Deylamites as non-Muslim. These chronicles also show that the Deylamites were the only warriors in the Caspian region who could fight the fearsome Varangian Vikings as equals. Deylamite mercenaries served as far away as Egypt, al-Andalus, and in the Khazar Kingdom.

The Buyids established the most successful of the Deylamite dynasties of Iran.

_4.jpg.webp)

In the 9th–11th century AD, there were repeated military raids undertaken by the Rus' between 864 and 1041 on the Caspian Sea shores of Iran, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan as part of the Caspian expeditions of the Rus'.[21] Initially, the Rus' appeared in Serkland in the 9th century traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves. The first small-scale raids took place in the late 9th and early 10th century. The Rus' undertook the first large-scale expedition in 913; having arrived on 500 ships, they pillaged the westernmost parts of Gorgan as well as Gilan and Mazandaran, taking slaves and goods.

The Turkish invasions of the 10th and 11th centuries CE, which saw the rise of Ghaznavid and Seljuk dynasties, put an end to Deylamite states in Iran. From the 11th century CE to the rise of Safavids, Gilan was ruled by local rulers who paid tribute to the dominant power south of the Alborz range but ruled independently.

In 1307 the Ilkhan Öljeitü conquered the region.[22] This was the first time the region came under the rule of the Mongols after the Ilkhanid Mongols and their Georgian allies failed to do it in the late 1270s.[23] After 1336, the region seemed to be independent again.

Before the introduction of silk production (date unknown but a pillar of the economy by the 15th century AD), Gilan was a poor province. There were no permanent trade routes linking Gilan to Persia. There was a small trade in smoked fish and wood products. It seems that the city of Qazvin was initially a fortress-town against marauding bands of Deylamites, another sign that the economy of the province did not produce enough on its own to support its population. This changed with the introduction of the silk worm in the late Middle Ages.

Early modern and modern history

Gilan recognized twice, for brief periods, the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire without rendering tribute to the Sublime Porte, in 1534 and 1591.[24]

The Safavid emperor, Shah Abbas I ended the rule of Khan Ahmad Khan (the last semi-independent ruler of Gilan) and annexed the province directly to his empire. From this point onward, rulers of Gilan were appointed by the Persian Shah. In the Safavid era, Gilan was settled by large numbers of Georgians, Circassians, Armenians, and other peoples of the Caucasus whose descendants still live or linger across Gilan. Most of these Georgians and Circassians are assimilated into the mainstream Gilaks. The history of Georgian settlement is described by Iskandar Beg Munshi, the author of the 17th century Tarikh-e Alam-Ara-ye Abbasi, and the Circassian settlements by Pietro Della Valle, among other authors.[25]

The Safavid empire became weak towards the end of the 17th century CE. By the early 18th century, the once-mighty empire was in the grips of civil war and uprisings. The ambitious Peter I of Russia (Peter the Great) sent a force that captured Gilan and many of the Iranian territories in the North Caucasus, Transcaucasia, as well as other territories in northern mainland Iran, through the Russo-Persian War (1722-1723) and the resulting Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1723).[26] Gilan and its capital of Rasht, which was conquered between late 1722 and late March 1723, stayed in Russian possession for about ten years.[27]

Qajars established a central government in Persia (Iran) in the late 18th century CE. They lost a series of wars to Russia (Russo-Persian Wars 1804–1813 and 1826–28), resulting in an enormous gain of influence by the Russian Empire in the Caspian region, which would last up to 1946. The Gilanian cities of Rasht and Anzali were all but occupied and settled by Russians and Russian forces. Most major cities in the region had Russian schools and significant traces of Russian culture can be found today in Rasht. Russian class was mandatory in schools and the significant increase of Russian influence in the region lasted until 1946 and had a major impact on Iranian history, as it directly led to the Persian Constitutional Revolution.

Gilan was a major producer of silk beginning in the 15th century CE. As a result, it was one of the wealthiest provinces in Iran. Safavid annexation in the 16th century was at least partially motivated by this revenue stream. The silk trade, though not the production, was a monopoly of the Crown and the single most important source of trade revenue for the imperial treasury. As early as the 16th century and until the mid 19th century, Gilan was the major exporter of silk in Asia. The Shah farmed out this trade to Greek and Armenian merchants and, in return, received a handsome portion of the proceeds.

In the mid-19th century, a fatal epidemic among the silk worms paralyzed Gilan's economy, causing widespread economic distress. Gilan's budding industrialists and merchants were increasingly dissatisfied with the weak and ineffective rule of the Qajars. Re-orientation of Gilan's agriculture and industry from silk to production of rice and the introduction of tea plantations were a partial answer to the decline of silk in the province.

After World War I, Gilan came to be ruled independently of the central government of Tehran and concern arose that the province might permanently separate. Before the war, Gilanis had played an important role in the Constitutional Revolution of Iran. Sepahdar-e Tonekaboni (Rashti) was a prominent figure in the early years of the revolution and was instrumental in defeating Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar.

In the late 1910s, many Gilanis gathered under the leadership of Mirza Kuchik Khan, who became the most prominent revolutionary leader in northern Iran in this period. Khan's movement, known as the Jangal movement of Gilan, had sent an armed brigade to Tehran that helped depose the Qajar ruler Mohammad Ali Shah. However, the revolution did not progress the way the constitutionalists had strived for, and Iran came to face much internal unrest and foreign intervention, particularly from the British and Russian empires.

During and several years after the Bolshevik Revolution, the region saw another massive influx of Russian settlers (the so-called White émigrées). Many of the descendants of these refugees are in the region. During the same period, Anzali served as the main trading port between Iran and Europe.

The Jangalis are glorified in Iranian history and effectively secured Gilan and Mazandaran against foreign invasions. However, in 1920 British forces invaded Bandar-e Anzali, while being pursued by the Bolsheviks. In the midst of this conflict, the Jangalis entered into an alliance with the Bolsheviks against the British. This culminated in the establishment of the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic (commonly known as the Socialist Republic of Gilan), which lasted from June 1920 until September 1921.

In February 1921 the Soviets withdrew their support for the Jangali government of Gilan and signed the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship (1921) with the central government of Tehran. The Jangalis continued to struggle against the central government until their final defeat in September 1921 when control of Gilan returned to Tehran.

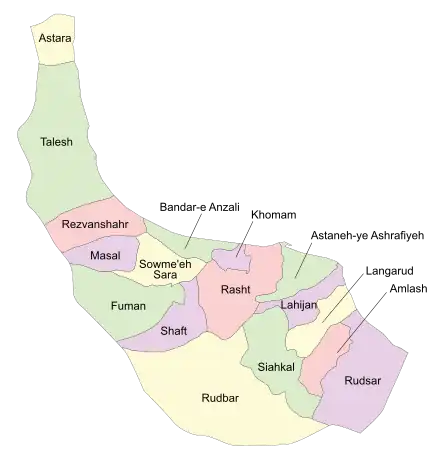

Administrative divisions

| Administrative Divisions | 2006[12] | 2011[13] | 2016[1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amlash County | 46,108 | 44,261 | 43,225 |

| Astaneh-ye Ashrafiyeh County | 107,801 | 105,526 | 108,130 |

| Astara County | 79,416 | 86,757 | 91,257 |

| Bandar-e Anzali County | 130,851 | 138,004 | 139,016 |

| Fuman County | 96,788 | 93,737 | 92,310 |

| Khomam County1 | — | — | — |

| Lahijan County | 161,491 | 168,829 | 167,544 |

| Langarud County | 133,133 | 137,272 | 140,686 |

| Masal County | 47,648 | 52,496 | 52,649 |

| Rasht County | 847,680 | 918,445 | 956,971 |

| Rezvanshahr County | 64,193 | 66,909 | 69,865 |

| Rudbar County | 101,884 | 100,943 | 94,720 |

| Rudsar County | 144,576 | 144,366 | 147,399 |

| Shaft County | 63,375 | 58,543 | 54,226 |

| Siahkal County | 46,991 | 47,096 | 46,975 |

| Sowme'eh Sara County | 129,629 | 127,757 | 125,074 |

| Talesh County | 179,499 | 189,933 | 200,649 |

| Total | 2,381,063 | 2,480,874 | 2,530,696 |

| 1Separated from Rasht County | |||

Cities

According to the 2016 census, 1,598,765 people (over 63% of the population of Gilan province) live in the following cities: Ahmadsargurab 2,128, Amlash 15,444, Asalem 10,720, Astaneh-ye Ashrafiyeh 44,941, Astara 51,579, Bandar-e Anzali 118,564, Barehsar 1,612, Bazar Jomeh 5,729, Chaboksar 8,224, Chaf and Chamkhaleh 8,840, Chubar 5,554, Deylaman 1,729, Fuman 35,841, Gurab Zarmikh 4,840, Hashtpar 54,178, Haviq, 4,261, Jirandeh 2,320, Kelachay 12,379, Khomam 20,897, Khoshk-e Bijar 7,245, Kiashahr 14,022, Kuchesfahan 10,026, Kumeleh 6,457, Lahijan 101,073, Langarud 79,445, Lasht-e Nesha 10,539, Lavandevil 11,235, Lisar 3,647, Lowshan 13,032, Luleman 7,426, Maklavan 1,635, Manjilabad 15,630, Marjaghal 6,735, Masal 17,901, Masuleh 393, Otaqvar 1,938, Pareh Sar 8,016, Rahimabad 10,571, Rankuh 2,154, Rasht 679,995, Rezvanshahr 19,519, Rostamabad 13,746, Rudbar 10,504, Rudboneh 3,441, Rudsar 37,998, Sangar 12,583, Shaft 8,184, Shalman 5,102, Siahkal 19,924, Sowme'eh Sara 47,083, Tutkabon 1,510, and Vajargah 4,537.[1]

Geography and climate

.jpg.webp)

Gilan has a humid subtropical climate with, by a large margin, the heaviest rainfall in Iran: reaching as high as 1,900 millimetres (75 in) in the southwestern coast and generally around 1,400 millimetres (55 in). Rasht, the capital of the province, is known internationally as the "City of Silver Rains" and in Iran as the "City of Rain".

Rainfall is heaviest between September and December because the onshore winds from the Siberian High are strongest, but it occurs throughout the year though least abundantly from April to August. Humidity is very high because of the marshy character of the coastal plains and can reach 90 percent in summer for wet bulb temperatures of over 26 °C (79 °F). The Alborz range provides further diversity to the land in addition to the Caspian coasts.

The coastline is cooler and attracts large numbers of domestic and international tourists. Large parts of the province are mountainous, green and forested. The coastal plain along the Caspian Sea is similar to that of Mazandaran and mainly used for rice paddies. Due to successive cultivation and selection of rice by farmers, several cultivars including Gerdeh, Hashemi, Hasani, and Gharib have been bred.[28]

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

Gilaks form the majority of the population, while Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Talysh and Persians are significant minorities in the province. Gilaks live in most of the cities and villages in the province, except Astara and Hashtpar counties.

The city and county of Astara are inhabited by majority Azerbaijanis.

There are four groups of Kurds in the province with different origins. Amarlou in Rasht and Rudbar (Districts of Ammarlu, Deylaman, and Raḥmatabad), Reshvand in Rasht, Jalalvand in Langroud, and Kormanj in Hashtpar.[29]

In Talysh county (Hashtpar), the majority are Talysh, and Azerbaijanis make up a significant portion of the population. There are also Kurdish-speaking Gormanj in Talysh county who are immigrants from Khalkhal of Ardabil province.

Persians are concentrated in the city of Rasht and are divided into immigrants from Tehran and other central Iranian cities, and the local Gilak people who have adopted the Persian language and became Persianized.[29]

The Gilaki language is a Caspian language, and a member of the northwestern Iranian language branch, spoken in Iran's Gilan, Mazandaran and Qazvin provinces.[30][31] Gilaki is one of the main languages spoken in the province of Gilan and is divided into three dialects: Western Gilaki, Eastern Gilaki, and Galeshi (in the mountains of Gilan and Mazandaran).[32] The western and eastern dialects are separated by the Sefid Roud.[33]

Although Gilaki is the most widely spoken language in Gilan, the Talysh language is also spoken in the province. There are only two cities in Gilan where Talyshi is exclusively spoken: Masal and Masoleh (although other cities speak Talyshi alongside Gilaki) while Talyshi is spoken mostly in the city of Astara, Hashtpar and surrounding towns.

The Kurdish language is used by Kurds who have moved to the Amarlu region.[34][35][36][37]

Persian[38] is also spoken in the province of Gilan as it is Iran's official language, requiring everyone to know Persian.

Heritage language data as of 2022:[39]

Mother tongue data as of 2022:[39]

Notable people

- Abdul Qadir Gilani

- Ebrahim Pourdavoud

- Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi Gilani, founder of Sharif University of Technology

- Ardeshir Mohassess, cartoonist

- Mirza Kuchek Khan, founder of Constitutionalist movement of Gilan

- Arsen Minasian

- Hazin Lahiji, poet

- Mohammad Taghi Bahjat Foumani, Twelver Shi'a Marja

- Ataollah Salehi

- Mahmoud Behzad

- Majid Samii, brain surgeon in Germany

- Fazlollah Reza, second head of Sharif University of Technology

- Mohammad Moin, prominent Iranian scholar of Persian literature and Iranology

- Houman Seyyedi

- Mahmoud Namjoo

- Alireza Jahanbakhsh, football player

- Jalal Hosseini, football player

- Hushang Ebtehaj, contemporary poet

- Mardavij, former king of Iran

- Khosrow Golsorkhi, journalist, poet, and communist activist

- Anoushiravan Rohani, pianist and composer

- Shardad Rohani, composer, violinist/pianist, and conductor

- Shahin Najafi, musician, singer, songwriter and political activist

Colleges and universities

- Gilan University of Medical Sciences

- Institute of Higher Education for Academic Jihad of Rasht

- Islamic Azad University of Bandar Anzali

- Islamic Azad University of Astara

- Islamic Azad University of Lahijan

- Islamic Azad University of Talesh

- Islamic Azad University of Rasht

- Payam-e-Noor University – Talesh

- Technical & Vocational Training Organization of Gilan

- University of Guilan

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Archived from the original (Excel) on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ↑ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Guilan Government Province website Archived 30 June 2011 at archive.today

- ↑ library Great Encyclopedia of Islam – Astara

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica:Manjil Archived 17 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "تالشی و تاتی بازمانده زبان ماد / بخش دوم". Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "شهر رضوانشهر". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "TalesHan.com". taleshan.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ↑ "「2022卡塔尔」世界杯买球赛平台". Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Archived 19 December 2012 at archive.today University of Guilán

- ↑ "همشهری آنلاین-استانهای کشور به ۵ منطقه تقسیم شدند (Provinces were divided into 5 regions)". Hamshahri Online (in Persian). 22 June 2014 [1 Tir 1393, Jalaali]. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006)". AMAR (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011)" (Excel). Iran Data Portal (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. p. 01. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- 1 2 Biglari, F., V. Jahani 2011 The Pleistocene Human Settlement in Gilan, Southwest Caspian Sea: Recent Research, Eurasian Prehistory 8 (1-2): 3-28

- ↑ Falahian Y. 2006a. Evidence of Neolithic occupation at Chapalak near Nodeh-e Farab, Journal of Gilan Culture, Nos. 25-26, pp. 8-12

- ↑ Biglari, F., and H. Abdi (2003) Discovery of Two Probable Late Paleolithic Sites at Amarlou, The Gilan Province, Caspian Basin, In T. Ohtsu, J.Nokandeh, and K. Yamauchi (eds), Preliminary Report of the Iran-Japan Joint Archaeological Expedition to Gilan, First Season, 2001, pp. 92-96, ICHO, Tehran, and MECC, Tokyo.

- ↑ Nasidze, Ivan; Quinque, Dominique; Rahmani, Manijeh; Alemohamad, Seyed Ali; Stoneking, Mark (2006). "Concomitant Replacement of Language and mtDNA in South Caspian Populations of Iran". Current Biology. 16 (7): 668–673. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.021. PMID 16581511. S2CID 7883334.

- ↑ The Tati language group in the sociolinguistic context of Northwestern Iran and Transcaucasia, D. Stilo, pages 137–185

- ↑ http://original.britannica.com/eb/article-22885/Iraq#147477.hook

- ↑ David Wilmshurst (2011), The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East, East and West Publishing, p. 166.

- ↑ Logan (1992), p. 201

- ↑ Charles Melville – "The Ilkhan Öljeitü's conquest of Gilan (1307): rumour and reality", in R. Amitai Preiss & D.O. Morgan (eds), The Mongol empire and its legacy, Leiden 1999, pp. 73–125

- ↑ "Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods, Armenian History, Turkish History, Mongol History, Georgian History, Armeno-Turcica". Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ Donald Edgar Pitcher (1968). An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire: From Earliest Times to the End of the Sixteenth Century. Brill Archive. p. 132. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018.

- ↑ Pietro Della Valle, Viaggi, 3 vols. in 4 parts, Rome, 1658–63; tr. J. Pinkerton as Travels in Persia, London, 1811.

- ↑ William Bayne Fisher, P. Avery, G. R. G. Hambly, C. Melville. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 7 Cambridge University Press, 10 okt. 1991 ISBN 0521200954 p 321

- ↑ The Caucasus in the System of International Relations: The Turkmanchay Treaty Was Signed 180 Years Ago Научная библиотека КиберЛенинка Archived 29 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine p 142

- ↑ Pazuki, Arman & Sohani, Mehdi (2013). "Phenotypic evaluation of scutellum-derived calluses in 'Indica' rice cultivars". Acta Agriculturae Slovenica. 101 (2): 239–247. doi:10.2478/acas-2013-0020.

- 1 2 "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ↑ ^ Coon, "Iran:Demography and Ethnography" in Encyclopedia of Islam, Volume IV, E.J. Brill, pp. 10,8. Excerpt: "The Lurs speak an aberrant form of Archaic Persian" See maps also on page 10 for distribution of Persian languages and dialect

- ↑ Kathryn M. Coughlin, "Muslim cultures today: a reference guide", Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. p. 89: "...Iranians speak Persian or a Persian dialect such as Gilaki or Mazandarani."

- ↑ "Gilaki".

- ↑ Leipzig, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. "Former Dept. of Linguistics – Northwest Iranian Project". eva.mpg.de. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ↑ Mirrazavi, Firouzeh (29 June 2014). "Gilan Province". Masjed.ir. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020.

- ↑ "A Paradise: Gilan, North of Iran". Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ↑ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ↑ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ↑ "پرتال استان گيلان – جمعيت و نيروي انساني". Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Language distribution: Gilan Province". 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

External links

- Guilan.net

- Association of Guilan Supporters Official website (in Persian only)

- Gilan entry in the Encyclopædia Iranica

- "A first detailed language map of Gilan Province, Iran" (PDF). Hamideh Poshtvan, Carleton University.

- Gilan University of Medical Sciences Health Information Center (in English)

- Gilan Cultural Heritage Organization (An excellent source of info in Persian)

- Masouleh Village Official website (inaccessible to English readers)

- Shapour Bahrami, Masouleh, Iran, Photo Set, flickr.

- Gilan Province Office of Tourism

- Houchang E. Chehabi (ed.). "Regional Studies: Gilan". Bibliographia Iranica. USA: Iranian Studies Group at MIT. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2017. (Bibliography)

- Gilan Province Department of Education (in Persian)

- Two Gilani folk-songs sung by Shusha Guppy in the 1970s: The Rain, Darling Leila.

- Āhā Bugu (Oh, say it!), a Gilaki folk-song: Video on YouTube (4 min 54 sec).

- Pazuki, Arman & Sohani, Mehdi (2013). "Phenotypic evaluation of scutellum-derived calluses in 'Indica' rice cultivars". Acta Agriculturae Slovenica. 101 (2): 239–247. doi:10.2478/acas-2013-0020.

- Hamid-Reza Hosseini, Rural Heritage, in Persian, Jadid Online, 17 November 2008, .

A shortened version in English with the title Gilan's Rural Geritage Museum, Jadid Online, 22 January 2009: .

A slide show of Gilan's Rural Heritage Museum with English subtitles, Jadid Online, 22 January 2009: (5 min 41 sec). - Mohammad-Taqi Pourahmad Jacktaji, Gilan Midsummer Nowruz, in English, Jadid Online, 1 October 2009, (in Persian: ).

An audio slideshow with English subtitles: (4 min 38 sec).