Gabriel Guay | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 15 October 1848 La Chapelle (now part of Paris), France |

| Died | 15 September 1923 (aged 74) Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, France |

| Education | student of Jean-Léon Gerôme and Justin Lequien |

| Works | La dernière dryade (1898) |

| Awards | Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, 1892[1] |

Gabriel Guay (October 14, 1848 – September 15, 1923), whose full name was Julien Gabriel Guay, was a French painter and teacher. From 1873 he exhibited works at the annual Paris Salon. He painted portraits, and also scenes inspired by literature, mythology, the Bible, and Christian martyrdom. His reverence for nature and especially for trees, combined with his affinity for the female nude, resulted in his most distinctive and widely exhibited paintings, depicting dryads in the woods.

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

Guay was born in 1848 in a northern Parisian suburb, the village of La Chapelle; in 1859 it was incorporated into the 18th arrondissement of Paris. His parents were Jules Antoine Guay and Louise Joséphine Cottin. After his death in 1923 he was survived by his widow, Virginie Alexandrine Lequin.[2][3]

His circle of friends included the artists Édouard Debat-Ponsan, Edmond Debon, Adrien Demont, Virginie Demont-Breton, Octave Jahyer, Henri Pille, Tony Robert-Fleury, and François Thévenot;[4] the painter Edmond Yon, in whose garden at Rue Lepic, n° 59, Guay painted nature studies;[5] and the author Léon Roger-Milès, who dedicated to Guay his story "Une Vision d'Allori", which imagines a dream of the Florentine painter Cristofano Allori as a starting point for a rapturous meditation on the transcendent beauty of the female nude.[6]

The popular singer-comedian Ernest Gibert (who was to die in a spectacular accident a few weeks later)[7] entertained at an 1892 New Year's Eve party chez Guay.[8] One of Guay's paintings of a rustic farm house, in Vosges, is inscribed, "à Gibert, souvenir amical."

Career

.jpg.webp)

Guay was a student of Justin Lequien and of Jean-Léon Gerôme, from whom he learned the exacting skills of French Academic painting. In 1873, at the age of 24, he had a painting accepted for exhibition at the annual Paris Salon, the traditional starting point for the career of a French artist of the 19th century; the work was Ulysse suspendu sur le gouffre de Charybde, inspired by a passage in Homer's Odyssey.[9]

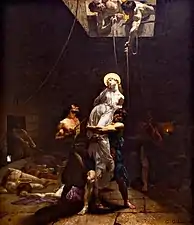

His Academic training is evident in his meticulously detailed and scrupulously finished early works which treat mythological and religious subjects, including Laton et le paysans (1877), Le Lévite d'Ephraim (1878), and Le Tullianum pendant la persécution; martyre de Sainte Pauline (1880).[9]

By 1877 some of his paintings had made their way to San Francisco, where the art dealers Snow and May sold two of his works at auction, The Anglers and A Fishing Party.[10][11] Another work by Guay created a sensation in San Francisco at the 15th Mechanics' Fair of 1880.

The Awakening showed a nude woman, life-size, lying on her side and just waking up. The figure was gracefully posed, the drawing faultless, the flesh tones soft and lucid. In short, wrote the Californian, it was "a splendid study of the female form." Even so, the moralists had reservations.…The nude in The Awakening was too realistic, "the work of a Zola." She was too contemporary, a modern-day woman, "the very embodiment of flesh, blood, and passion," portrayed after what some said was surely a night of debauchery.…Alarmed, the fair managers hung an unsightly red drapery over the offending nude as they tried to decide what to do next.…Gallery visitors, young and old, took to peeping behind the drapery [which] kept falling down, so a policeman was posted next to the painting to ensure public safety until…a vote would be taken among gallery visitors to determine whether The Awakening should stay or go. On the day of the vote…it soon became obvious that The Awakening had more admirers than adversaries. "Speaking in a general way," wrote the Chronicle the next day, "all the good-natured, sleek and healthy people appeared to be in favor of allowing the picture to remain and all the dyspeptic and melancholy ones determined to have it removed."[12]

On the day of the vote, 12,808 people bought tickets to the fair. The vote to unveil The Awakening prevailed in a landslide.[13]

Guay's interest in the female nude, often seen from the back, continued throughout his career. Farniente (Lazing), from 1911, shows a sleeping nude, and in 1912, his submission to the Salon was simply titled Nu (Nude); both images were issued as souvenir postcards, presumably acceptable for delivery in the French post.

The whereabouts of a number of his paintings are unknown. His Cosette of 1882, depicting the character from Les Misérables, is known today only from reproductions, one of which, an albumen print now at the Maison de Victor Hugo, he inscribed to the author: "A Victor Hugo, notre illustre poète national, Hommage de son grand admirateur, Gabriel Guay." His genre painting En l'absence du maître (While the Master's Away) of 1877 is also known only from reproductions, including a full-page engraving published in L'illustration: journal universel.[14]

A Fishing Party, 1876

A Fishing Party, 1876.tif.jpg.webp) En l'absence du maître, 1877

En l'absence du maître, 1877 Latone et les paysans, 1877

Latone et les paysans, 1877 Le Lévite d'Ephraïm, 1878

Le Lévite d'Ephraïm, 1878 Le Tullianum, 1880

Le Tullianum, 1880.tif.jpg.webp) Cosette, 1882

Cosette, 1882.png.webp) La mort de Jézabel, 1888

La mort de Jézabel, 1888.jpg.webp) Farniente, 1911

Farniente, 1911 Nu, 1912

Nu, 1912

At least one of his paintings is known to have been destroyed in the carnage of World War II: La mort de Jézabel, exhibited at the Salon of 1888, where it inspired the critic Henry Houssaye to write a vivid description:

On the hard slabs, at the foot of a massive square tower covered at its base with blue tiles, lies with its head in front and arms outstretched the corpse of the Queen of Israel. In Jezebel's supreme struggle with her murderers, her dark green dress of shimmering velvet was torn and half-destroyed. Her beautiful white body is naked above the belt, and her red hair spreads over the granite like a flood of molten copper. On the left, in the crepuscular twilight, a street recedes in perspective, creating a singular optical illusion. Packs of carnivorous dogs approach, mouths gaping and eyes ablaze. Despite the murder that has just been committed and despite the carnage about to occur, we are less moved by the drama than we are struck by the power of the execution and seduced by the charm of the coloring. This supple white body, with golden halftones and gray-blue shadows, still throbs with life. It stands out with surprising relief and incomparable brilliance.[15]

The painting also caught the eye of Thomas Hardy, who wrote: "At the Salon. Was arrested by the sensational picture called The Death of Jezabel...a horrible tragedy, and justly so, telling its story in a flash."[16] Hardy scholar Dennis Taylor, trying to track down the painting almost a century later, was informed by René Le Bihan, curator of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Brest, "Alas, this painting disappeared amid the annihilation of our museum in 1941, and we have no trace of it, not a photograph or engraving or drawing."[16] An image has since been located, in an issue of Firmin Javel's L'Art français from 1888.

Guay painted portraits from the beginning of his career, and after the turn of the century the majority of paintings he exhibited at the Paris Salon were portraits. Of his portraits the only example we have is his painting of an old man in a garden (perhaps Guay's grandfather[9]), at the Musée des beaux-arts de Morlaix.

Villages and farm houses

While Guay's submissions to the Salon followed the rigorous standards of Academic art, and were sometimes quite large, he also painted a series of smaller works depicting rustic villages and farm houses in locations including Brittany and the Vosges region of France. Often executed in oil on panel, presumably painted en plein air, these display a looser, almost impressionistic brushwork, and may have been made as studies, souvenirs, and gifts. They are signed but not dated, making them difficult to place in the chronology of Guay's career. However, one of the paintings is inscribed, "Vosges, village de [uncertain], à Gibert, souvenir amical." If the recipient was the singer-comedian Ernest Gibert (who was a friend of Guay), a terminus ante quem of 1893 for the painting can be established by the death of Gibert in March of that year.[7][8]

Signed and inscribed: "Vosges…à Gibert, souvenir amical", by 1893

Signed and inscribed: "Vosges…à Gibert, souvenir amical", by 1893 La pêche à la ligne

La pêche à la ligne Young girl gathering water, at Saint-Omer, Marais

Young girl gathering water, at Saint-Omer, Marais Bretonne devant le puits

Bretonne devant le puits Paysage poitevin

Paysage poitevin La petite famille

La petite famille Village street

Village street

Dryads

It was in his paintings of forests and dryads that Guay most distinctly expressed his artistic vision and most successfully struck a chord with popular taste and critical reception; "his talent was transformed in the attentive study of nature."[9] Guay was inspired by the female tree spirits of Greek mythology, and also by a centuries-old current in French literature that perceived a mystical or spiritual power in trees and lamented the felling of a tree as a kind of murder.

Guay's dryad series began with Poème des bois, which became his most widely exhibited picture. It was shown at the Paris Salon of 1889, where it received a silver medal; at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, where it received another silver medal; and at the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908 in London. The conception was simple: a number of nude women lie amid fallen leaves in an autumnal forest. An ethereal light introduces a note of the uncanny. The painting was purchased by the French State and deposited at the Musée de Draguinan. Its present location is unknown and the image is known only from reproductions.

La mort du chêne (The Death of the Oak) followed in 1891, inspired by a poem by Victor de Laprade: "When the man struck you with his cowardly ax,/O king whom the mountain yesterday carried with pride,/My soul, at the first blow, resounded with indignation,/And in the holy forest there was great mourning…"[17][18] The location of the painting is unknown.

La dernière dryade appeared in 1898. It is the best-known of Guay's works, having survived intact in the collection of the Musée des Augustins de Toulouse. The painting was inspired by a poem by Émile Blémont: "A mournful silence filled the great woods,/Once peopled with such sweet visions./Pan had just expired. 'Fall, O red leaves!/Fall!' cried the weeping Dryad in a dying voice." The faded Greek letters on the pedestal translate: "Pan, beloved of the amorous Dryads."[19] The critic Antonin Proust wrote, "The impression is so truthful, the autumn feeling is so tangible, that we can but feel grateful to M. Guay for so successfully bringing before us a thing we have so often seen."[20]

.jpg.webp) Poème des bois, 1889

Poème des bois, 1889.tif.jpg.webp) La mort du chêne, 1891

La mort du chêne, 1891.png.webp) Les grives, 1899

Les grives, 1899 Les bourreaux des bois, 1909

Les bourreaux des bois, 1909 La Couture, undated

La Couture, undated Amour! (study), undated

Amour! (study), undated

Les grives (The Thrushes) was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1899. It was shown again at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, along with Poème des bois. Here the dryads, like hungry thrushes, are entwined amid grape vines, shimmering with dew and the blood-red juice of crushed grapes ("du sang des grappes écrasées" according to the uncredited verses in the Salon program).[21] The critic Camille Le Senne praised its "rare luminous qualities" and "undeniable poetic charm."[22] The painting is now known only from poor reproductions.

Guay's dryad series culminated with Les bourreaux des bois (Executioners of the Woods), again inspired by a poem, this one very old: "Contre les bûcherons de la forêt de Gastine" (Against the Lumberjacks of the Forest of Gastine) by Pierre de Ronsard (1524-1585). (Another inspiration may have been the poem "Pour les Arbres" by François Fabié, published in 1906, which cites Ronsard and uses the phrase "les bourreaux des bois".[23]) The painting was exhibited twice at the Paris Salon, in 1909 and again in 1914, on the eve of World War I. One reviewer called it

A truly beautiful work…in which realism and poetry are intelligently combined. Loggers have cut down large trees and made a clearing in the dense forest. The victims of the ax lie on the ground. Their executioners rest seated on the tree trunks and warm themselves over a large fire. One still holds his ax between his legs…his rough face seems uneasy about the act accomplished; the others, with indifferent faces, warm themselves while smoking their pipes. On the left arrives a lumberjack bringing a bundle to stoke the fire. The flame sparkles, a bluish smoke spreads in the clearing and rises towards the sky. Look closely, and you will discover silhouettes of nymphs and fauns; they are the forest divinities for whom the poet Ronsard wept, being carried away in this cloud of smoke. Henceforth the forest will have lost its magic and mystery…M. Gabriel Guay's painting is one of the most impressive at the Salon: it commands the attention of the indifferent.[24]

The English critic Henry Heathcote Statham, perhaps noting the demonic appearance of one figure in the smoke, perceived a note of menace, saying "the woodcutters felling trees are threatened with vengeance by an apparition of nymphs."[25] The poem by Ronsard is a lament, but also calls for harsh justice: "Murderous sacrilege! If we hang a thief/For plundering booty of very little value,/How many fires, irons, deaths and distress/Do you deserve, villain, for killing our goddesses?"

Depicting women and trees, Guay could also display a sense of humor. The undated work La Couture presents a domesticated dryad; a very real woman, not naked but entirely clothed, is perched on the stump of a tree not unlike a pedestal, content to sew. The undated study Amour! depicts a nude Aphrodite in the forest, seated on a felled tree. Bald acolytes tend a wood-burning fire at her feet.

Legacy

The year after his death, the Paris Salon of 1924 acknowledged Guay's passing with a retrospective of his work at the Grand Palais.[26]

Along with painting, Guay was also a teacher, serving as a professor of drawing at the Ecole Municipale Supérieure Turgot from at least 1898 to 1912.[9][27][28] Some of his students also became students of Jean-Léon Gerôme, Guay's own mentor. After Gerôme's death in 1904, Guay carried forward the principles of Academic art into the 20th century, even as it faded from fashion, a once mighty forest felled by Impressionism.

In museums and other buildings

Guay's works in museums, listed in chronological order, include:

- Château du Roi René, Peyrolles-en-Provence, France: Latone et les paysans, 1877.

- Musée de Grenoble, France: Le Lévite d'Ephraïm, 1878.

- Museo del Palacio Vergara, Viña del Mar, Chile: Le Tullianum pendant la persécution; martyre de Sainte Pauline, 1880.

- Maison de Victor Hugo, Paris: Cosette, 1882; albumen print inscribed to Victor Hugo and signed by Guay.

- Musée des Augustins de Toulouse, France: La dernière dryade, 1898.

- Musée des beaux-arts de Morlaix, France: Un viellard assis dans un jardin (perhaps Guay's grandfather[9]), by 1899.

- Église Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles de Bagnolet, Paris: Christ donnant les clefs à Saint Pierre, by 1904.[9]

- Mairie (town hall), Bourges, France: Les bourreaux des bois, 1909.

- Mairie (town hall), Le Faouët, Morbihan, France: Paysage poitevin, undated.

References

- ↑ "N° de Notice : c-210642". leonore.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ↑ "1923, Décès, 18, page view 11/31, entry no. 3792". archives.paris.fr. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ↑ "Lequin" may be a misspelling of "Lequien," in which case she may have been related to Guay's teacher Justin Lequien.

- ↑ Nouvelles & Echos (1893): All were guests at Guay's 1892 New Year's Eve party, along with Edmond Yon and Ernest Gibert.

- ↑ Hustin, p. 19.

- ↑ Roger-Milés, pp. 81-87.

- 1 2 "Nécrologie" (1893).

- 1 2 Nouvelles & Echos (1893)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "GUAY Gabriel" (1905).

- ↑ "Gabriel Guay". northpointgallery.com. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ↑ The latter may be the painting now known as A Fishing Party on the Seine, which is signed by Guay and dated 1876.

- ↑ Hjalmarson, pp. 121-125, quoting and citing contemporary newspaper accounts.

- ↑ Gary Kamiya (March 6, 2015). "Bare majority: victory for nude art in unusual election". sfgate.com.

- ↑ L'illustration: journal universel, issue number 1816, December 15, 1877, illustration p. 380, text p. 375. The uncredited text that describes the painting is unabashedly racist.

- ↑ Houssaye, p. 45-46.

- 1 2 Taylor, p. 171

- ↑ Explication… (1891), p. 67.

- ↑ Hustin, p. 19; illustration facing page 18.

- ↑ Roschach, p. 76.

- ↑ Proust, p. 50, who quotes Blémont.

- ↑ Explication (1899), p. 88.

- ↑ Le Senne, p. 148.

- ↑ Fabié, p. 801: "Et nous, depuis Ronsard…Maudissons les bourreaux des bois..."

- ↑ Bruand, pp. 411-412.

- ↑ Statham, p. 1361.

- ↑ Escholier, p. 109.

- ↑ Keller (1898), p. 2.

- ↑ Keller (1912), p. 38.

Sources

- Bruand, L. "Tournée Forestière aux Salons de Peinture de 1914", Revue des Eaux et Forêts, vol. 53, 1914–1915, pp. 409–415.

- Escholier, Raymond. "Le Salon", Le Correspondant, July 10, 1924, pp. 103–118.

- Explication des ouvrages de peinture…des artistes vivants exposé a la Galerie des Machines le 1er Mai 1889 (catalogue of the Paris Salon), Paris: Paul Dupont,1889.

- Explication des ouvrages de peinture…des artistes vivants exposé au palais des Champs-Élysée le 1er Mai 1891 (catalogue of the Paris Salon), Paris: Paul Dupont,1891.

- Fabié, François. "Pour les Arbres", Le Correspondant, November 25, 1906, pp. 801–804.

- "GUAY Gabriel" in Le Livre d'or des peintres exposants vivants au janvier 1903, Second Edition, Paris, 1905, pp. 243–244.

- Hjalmarson, Birgitta. Artful Players: Artistic Life in Early San Francisco, Los Angeles: Balcony Press, 1999.

- Houssaye, Henry. Le Salon de 1888, Paris: Boussod, Valadon & Cie., 1888.

- Hustin A. Salon de 1891, Paris: Ludovic Baschet, 1891.

- Keller, Alfred, editor-in-chief. Le Moniteur du dessin, de l'architecture & des beaux-arts, April, 1898, p. 4 and April, 1912, p. 38.

- Le Senne, Camille. "À l'Exposition des Beaux-Arts" in Le Ménestrel: journal de musique, July 5, 1899, pp. 147–149.

- "Nécrologie", Le Ménestrel, vol. 59, no. 11, March 12, 1893, p. 88.

- Noël, Benoît and Hournon, Jean. Parisiana: la capitale des peintres au XIXème siècle, Paris : Presses Franciliennes, 2006.

- "Nouvelles & Echos", Gil Blas, January 2, 1893, p. 1.

- Proust, Antonin. Le Salon de 1898, Paris: Goupil & Cie, 1898; English translation by Henry Bacon, Goupil's Paris Salon of 1898, New York: Jean Boussod, Mansi, Jouant & Co., 1898.

- Roger-Milès, Léon. Les Heures d'une Parisienne (includes the story "Une Vision d'Allori", dedicated to Gabriel Guay, who provided the book's cover art), Paris: Flammarion, 1890.

- Roschach, Ernest. "113—La Deniére Dryade" in Catalogue des collections de peinture du Musée de Toulouse, 1922, p. 76.

- Statham, H. Heathcote. "The Salon and the Royal Academy" in The Nineteenth Century and After, London and New York, vol 75, no. 448, June 1914, pp. 1358–1370.

- Taylor, Dennis. Hardy's Poetry: 1860-1928, New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

External links

- Elégies, XXIV, Contre les bûcherons de la forêt de Gastine by Pierre de Ronsard (1524-1585), complete text of the poem that inspired Guay's painting Les bourreaux des bois (in French).

- La mort d'un chêne by Victor de Laprade (1812-1883), complete text of the poem that inspired Guay's painting La mort du chêne (in French).