This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Galician language.

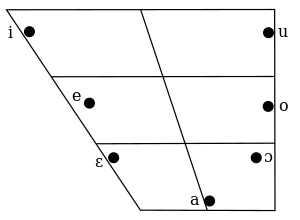

Vowels

Galician has seven vowel phonemes, which are represented by five letters in writing. Similar vowels are found under stress in standard Catalan and Italian. It is likely that this 7-vowel system was even more widespread in the early stages of Romance languages.

| Phoneme (IPA) | Grapheme | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| /a/ | a | nada |

| /e/ | e | tres |

| /ɛ/ | ferro | |

| /i/ | i | min |

| /o/ | o | bonito |

| /ɔ/ | home | |

| /u/ | u | rúa |

Some characteristics of the vocalic system:

- In Galician the vocalic system is reduced to five vowels in post-tonic syllables, and to just three in final unstressed position: [ɪ, ʊ, ɐ] (which can instead be transcribed as [e̝, o̝, a̝]).[1] In some cases, vowels from the final unstressed set appear in other positions, as e.g. in the word termonuclear [ˌtɛɾmʊnukleˈaɾ], because the prefix termo- is pronounced [ˈtɛɾmʊ].[2][3]

- Unstressed close-mid vowels and open-mid vowels (/e ~ ɛ/ and /o ~ ɔ/) can occur in complementary distribution (e.g. ovella [oˈβeɟɐ] 'sheep' / omitir [ɔmiˈtiɾ] 'to omit' and pequeno [peˈkenʊ] 'little, small' / emitir [ɛmiˈtiɾ] 'to emit'), with a few minimal pairs like botar [boˈtaɾ] 'to throw' vs. botar [bɔˈtaɾ] 'to jump'.[4] In pretonic syllables, close-/open-mid vowels are kept in derived words and compounds (e.g. c[ɔ]rd- > corda [ˈkɔɾðɐ] 'string' → cordeiro [kɔɾˈðejɾʊ] 'string-maker'—which contrasts with cordeiro [koɾˈðejɾʊ] 'lamb').[4]

- The distribution of stressed close-mid vowels (/e/, /o/) and open-mid vowels (/ɛ/, /ɔ/) are as follows:[5]

- Vowels with graphic accents are usually open-mid, such as vén [bɛŋ], só [s̺ɔ], póla [ˈpɔlɐ], óso [ˈɔs̺ʊ], présa [ˈpɾɛs̺ɐ].

- Nouns ending in -el or -ol and their plural forms have open-mid vowels, such as papel [paˈpɛl] 'paper' or caracol [kaɾaˈkɔl] 'snail'.

- Second-person singular and third-person present indicative forms of second conjugation verbs (-er) with the thematic vowel /e/ or /u/ have open-mid vowels, while all remaining verb forms maintain close-mid vowels:

- bebo [ˈbeβʊ], bebes [ˈbɛβɪs̺], bebe [ˈbɛβɪ], beben [ˈbɛβɪŋ]

- como [ˈkomʊ], comes [ˈkɔmɪs̺], come [ˈkɔmɪ], comen [ˈkɔmɪŋ]

- Second-person singular and third-person present indicative forms of third conjugation verbs (-ir) with the thematic vowel /e/ or /u/ have open-mid vowels, while all remaining verb forms maintain close vowels:

- sirvo [ˈs̺iɾβʊ], serves [ˈs̺ɛɾβɪs̺], serve [ˈs̺ɛɾβɪ], serven [ˈs̺ɛɾβɪŋ]

- fuxo [ˈfuʃʊ], foxes [ˈfɔʃɪs̺], foxe [ˈfɔʃɪ], foxen [ˈfɔʃɪŋ]

- Certain verb forms derived from irregular preterite forms have open-mid vowels:

- preterite indicative: coubeches [kowˈβɛt͡ʃɪs̺], coubemos [kowˈβɛmʊs̺], coubestes [kowˈβɛs̺tɪs̺], couberon [kowˈβɛɾʊŋ]

- pluperfect: eu/el coubera [kowˈβɛɾɐ], couberas [kowˈβɛɾɐs̺], couberan [kowˈβɛɾɐŋ]

- preterite subjunctive: eu/el coubese [kowˈβɛs̺ɪ], coubeses [kowˈβɛs̺ɪs̺], coubesen [kowˈβɛs̺ɪŋ]

- future subjunctive: eu/el couber [kowˈβɛɾ], couberes [kowˈβɛɾɪs̺], coubermos [kowˈβɛɾmʊs̺], couberdes [kowˈβɛɾðɪs̺], couberen [kowˈβɛɾɪŋ]

- The letter names e [ˈɛ], efe [ˈɛfɪ], ele [ˈɛlɪ], eme [ˈɛmɪ], ene [ˈɛnɪ], eñe [ˈɛɲɪ], erre [ˈɛrɪ], ese [ˈɛs̺ɪ], o [ˈɔ] have open-mid vowels, while the remaining letter names have close-mid vowels.

- Close-mid vowels:

- verb forms of first conjugation verbs with a thematic mid vowel followed by -i- or palatal x, ch, ll, ñ (deitar, axexar, pechar, tellar, empeñar, coxear)

- verb forms of first conjugation verbs ending in -ear or -oar (voar)

- verbs forms derived from the irregular preterite form of ser and ir (fomos, fora, fose, for)

- verbs forms derived from regular preterite forms (collemos, collera, collese, coller)

- infinitives of second conjugation verbs (coller, pór)

- the majority of words ending in -és (coruñés, vigués, montañés)

- the diphthong ou (touro, tesouro)

- nouns ending in -edo, -ello, -eo, -eza, ón, -or, -oso (medo, cortello, feo, grandeza, corazón, matador, fermoso)

- Of the seven vocalic phonemes of the tonic and pretonic syllables, only /a/ has a set of different renderings (allophones), forced by its context:[6]

- All dialectal forms of Galician but Ancarese, spoken in the Ancares valley in León, have lost the phonemic quality of mediaeval nasal vowels. Nevertheless, any vowel is nasalized in contact with a nasal consonant.[8]

- The vocalic system of Galician language is heavily influenced by metaphony. Regressive metaphony is produced either by a final /a/, which tend to open medium vowels, or by a final /o/, which can have the reverse effect. As a result, metaphony affects most notably words with gender opposition: sogro [ˈsoɣɾʊ] ('father-in-law') vs. sogra [ˈsɔɣɾɐ] ('mother-in-law').[9] On the other hand, vowel harmony, triggered by /i/ or /u/, has had a large part in the evolution and dialectal diversification of the language.

- Diphthongs

Galician language possesses a large set of falling diphthongs:

| falling | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [aj] | caixa | 'box' | [aw] | autor | 'author' |

| [ɛj] | papeis | 'papers' | [ɛw] | deu | 'he/she gave' |

| [ej] | queixo | 'cheese' | [ew] | bateu | 'he/she hit' |

| [ɔj] | bocoi | 'barrel' | |||

| [oj] | loita | 'fight' | [ow] | pouco | 'little' |

There are also a certain number of rising diphthongs, but they are not characteristic of the language and tend to be pronounced as hiatus.[10]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||

| Plosive/Affricate | p | b | t | d | tʃ | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | θ | s | ʃ | ||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Phoneme (IPA) | Main allophones[11][12] | Graphemes | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /b/ | [b], [β̞] | b, v | bebo [ˈbeβ̞ʊ] '(I) drink', alba [ˈalβ̞ɐ] 'sunrise', vaca [ˈbakɐ] 'cow', cova [ˈkɔβ̞ɐ] 'cave' |

| /θ/ | [θ] (dialectal [s]) | z, c | macio [ˈmaθjʊ] 'soft', cruz [ˈkɾuθ] 'cross' |

| /tʃ/ | [tʃ] | ch | chamar [tʃaˈmaɾ] 'to call', achar [aˈtʃaɾ] 'to find' |

| /d/ | [d], [ð̞] | d | vida [ˈbið̞ɐ] 'life', cadro [ˈkað̞ɾʊ] 'frame' |

| /f/ | [f] | f | feltro [ˈfɛltɾʊ] 'filter', freixo [ˈfɾejʃʊ] 'ash-tree' |

| /ɡ/ | [ɡ], [ɣ] (dialectal [ħ]) | g, gu | fungo [ˈfuŋɡʊ] 'fungus', guerra [ˈɡɛrɐ] 'war', o gato [ʊ ˈɣatʊ] 'the cat' |

| /ɟ/ | [ɟ], [ʝ˕], [ɟʝ] | ll, i | mollado [moˈɟað̞ʊ] 'wet' |

| /k/ | [k] | c, qu | casa [ˈkasɐ] 'house', querer [keˈɾeɾ] 'to want' |

| /l/ | [l] | l | lúa [ˈluɐ] 'moon', algo [ˈalɣʊ] 'something', mel [ˈmɛl] 'honey' |

| /m/ | [m], [ŋ][13] | m | memoria [meˈmɔɾjɐ] 'memory', campo [ˈkampʊ] 'field', álbum [ˈalβuŋ] |

| /n/ | [n], [m], [ŋ][13] | n | niño [ˈniɲʊ] 'nest', onte [ˈɔntɪ] 'yesterday', conversar [kombeɾˈsaɾ] 'to talk', irmán [iɾˈmaŋ] 'brother' |

| /ɲ/ | [ɲ][13] | ñ | mañá [maˈɲa] 'morning' |

| /ŋ/ | [ŋ][13] | nh | algunha [alˈɣuŋɐ] 'some' |

| /p/ | [p] | p | carpa [ˈkaɾpɐ] 'carp' |

| /ɾ/ | [ɾ] | r | hora [ˈɔɾɐ] 'hour', coller [koˈʎeɾ] 'to grab' |

| /r/ | [r] | r, rr | rato [ˈratʊ] 'mouse', carro [ˈkarʊ] 'cart' |

| /s/ | [s̺, z̺] (dialectal [s̻, z̻])[14] | s | selo [ˈs̺elʊ] 'seal, stamp', cousa [ˈkows̺ɐ] 'thing', mesmo [ˈmɛz̺mʊ] 'same' |

| /t/ | [t] | t | trato [ˈtɾatʊ] 'deal' |

| /ʃ/ | [ʃ] | x[15] | xente [ˈʃentɪ] 'people', muxica [muˈʃikɐ] 'ash-fly' |

Voiced plosives (/ɡ/, /d/ and /b/) are lenited (weakened) to approximants or fricatives in all instances, except after a pause or a nasal consonant; e.g. un gato 'a cat' is pronounced [uŋ ˈɡatʊ], whilst o gato 'the cat' is pronounced [ʊ ˈɣatʊ].

During the modern period, Galician consonants have undergone significant sound changes that closely parallel the evolution of Spanish consonants, including the following changes that neutralized the opposition of voiced fricatives / voiceless fricatives:

- /z/ > /s/;

- /dz/ > /ts/ > [s] in western dialects, or [θ] in eastern and central dialects;

- /ʒ/ > /ʃ/;

For a comparison, see Differences between Spanish and Portuguese: Sibilants. Additionally, during the 17th and 18th centuries the western and central dialects of Galician developed a voiceless fricative pronunciation of /ɡ/ (a phenomenon called gheada). This may be glottal [h], pharyngeal [ħ], uvular [χ], or velar [x].[16]

The distribution of the two rhotics /r/ and /ɾ/ closely parallels that of Spanish. Between vowels, the two contrast (e.g. mirra [ˈmirɐ] 'myrrh' vs. mira [ˈmiɾɐ] 'look'), but they are otherwise in complementary distribution. [ɾ] appears in the onset, except in word-initial position (rato), after /l/, /n/, and /s/ (honra, Israel), where [r] is used.

As in Spanish, /ɟ/ derives from historical /ʎ/ (yeísmo) and from syllable-initial /j/. In some dialects, it lenites to approximant [ʝ˕] in the same environments where /b, d, ɡ/ lenite. It may also be realized as [ɟʝ] where it derives from /j/. The realization [ʎ] remains in select older speakers in isolated regions.[12]

References

- ↑ E.g. by Regueira (2010)

- ↑ Regueira (2010:13–14, 21)

- ↑ Freixeiro Mato (2006:112)

- 1 2 Freixeiro Mato (2006:94–98)

- ↑ "Pautas para diferenciar as vogais abertas das pechadas". Manuel Antón Mosteiro. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ↑ Freixeiro Mato (2006:72–73)

- ↑ "Dicionario de pronuncia da lingua galega: á". Ilg.usc.es. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ Sampson (1999:207–214)

- ↑ Freixeiro Mato (2006:87)

- ↑ Freixeiro Mato (2006:123)

- ↑ Freixeiro Mato (2006:136–188)

- 1 2 Martínez-Gil (2022), pp. 900–902.

- 1 2 3 4 The phonemes /m/, /n/, /ɲ/ and /ŋ/ coalesce in implosive position as the archiphoneme /N/, which, phonetically, is usually [ŋ]. Cf. Freixeiro Mato (2006:175–176)

- ↑ Regueira (1996:82)

- ↑ x can stand also for [ks]

- ↑ Regueira (1996:120)

Bibliography

- Freixeiro Mato, Xosé Ramón (2006), Gramática da lingua galega (I). Fonética e fonoloxía (in Galician), Vigo: A Nosa Terra, ISBN 978-84-8341-060-8

- Martínez-Gil, Fernando (2022), "Galician", in Gabriel, Christoph; Gess, Randall; Meisenburg, Trudel (eds.), Manual of Romance Phonetics and Phonology, Berlin: De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-054835-8

- Regueira, Xosé Luís (1996), "Galician", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 26 (2): 119–122, doi:10.1017/s0025100300006162

- Regueira, Xosé Luís (2010), Dicionario de pronuncia da lingua galega (PDF), A Coruña: Real Academia Galega, ISBN 978-84-87987-77-9

- Sampson, Rodney (1999), Nasal vowel evolution in Romance, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, ISBN 978-0-19-823848-5