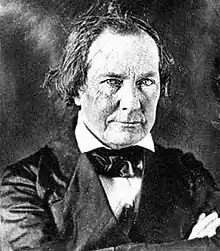

Gazaway Bugg Lamar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 2, 1798 |

| Died | October 5, 1874 (aged 76) Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Children | Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar (son) |

Gazaway Bugg Lamar (October 2, 1798 – October 5, 1874) was an American enslaver and merchant in cotton and shipping in Savannah, Georgia, and a steamboat pioneer. He was the first to use a prefabricated iron steamboat on local rivers, which was a commercial success. In 1846 he moved to New York City for business, where in 1850 he founded the Bank of the Republic on Wall Street and served as its president. He served both Southern businesses and state governments. After the start of the American Civil War, Lamar returned to Savannah, where he became active in banking and supporting the Confederate war effort in several ways. With associates, he founded the Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia, which operated blockade runners.

In December 1864, with Union General Sherman's troops approaching Savannah, Lamar took President Lincoln's loyalty oath (sometimes called the Proclamation of Amnesty) to uphold the United States constitution, in return for the promise that all his property rights would be restored. A high proportion of cotton confiscated in the city by Sherman belonged to Lamar. After the war he was arrested and held for three months in Washington, D.C., as a suspect in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

After returning to Savannah, Lamar tried to reclaim his cotton from warehouses in Georgia and Florida. He was arrested and convicted by a military court under Reconstruction of trying to take government property and bribe a government official. His sentence was commuted by President Andrew Johnson shortly before the end of his term. Lamar spent years trying to gain compensation for his confiscated cotton. In 1874, he was awarded a government settlement of almost US$580,000 (equivalent to $15,001,529 in 2022).

Early life and career

Born in 1798 near Augusta, Georgia (likely in the Sand Hills area), he was the third of twelve children of Basil Lamar and Rebecca Kelly. They were descendants of French immigrant Thomas Lamar, who settled in Maryland in 1660. Among his siblings was G. W. Lamar, who became a prominent banker in Augusta.[1] He and his family had many connections to other leaders in the South. Brothers Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus and Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar were first cousins from Georgia; the former became a judge in Georgia; the latter served as the second President of the Republic of Texas.[1]

Gazaway's father was a charter member of the Steamboat Company of Georgia. The family moved to Savannah in the 1830s. By the time of his father's death when Lamar was 29, he had become active in the shipping and factoring business in Savannah and Augusta.

Marriage and family

In 1821 he married Jane Meek Cresswell of Savannah. They had six children together. She died in 1838 in the Steamship Pulaski disaster, when one of the ship's boilers exploded and the ship sank. Some 128 persons died in the accident, including their three daughters and two of three sons, and a niece,[2] along with numerous other passengers and crew. This was in the course of a voyage from Savannah to Baltimore, Maryland. Lamar and their eldest son Charles survived the sinking.

Lamar married again, to Harriet Cazenove of Virginia. He moved with his son Charles to live with her for a year in Alexandria, Virginia, before returning with them to Savannah.[2]

Career

Lamar's business activities in Savannah included banking, ship owning, cotton factoring, insurance, and warehousing.[2] In 1834 an act was passed in the U. S. Congress allowing Lamar to "import free of duty any iron steamboat...for the purpose of making an experiment of the aptitude of iron steamboats for the navigation of shallow waters..."

In 1834 he arranged for a pre-fabricated iron steamboat to be shipped from Great Britain; it was re-assembled at a Savannah shipyard. This boat was named the SS John Randolph. It became a great commercial success as a model for use as a river steamboat, leading to development of a business. It is commemorated with an historical marker in Savannah next to the Maritime Fountain on River Street, titled SS Savannah and SS John Randolph. The SS Savannah was the first steamboat to cross the Atlantic, in 1819.[3] During this time in Savannah, Lamar sold at least one steamboat, named the Zavala, to the Republic of Texas while his cousin Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar was president of the independent nation.

By 1846 Lamar had moved with his family to New York City. He and his second wife had a total of six children together, with the youngest ones born there.[2]

In 1850, along with some associates, Lamar founded the Bank of the Republic with $1,000,000 (~$27.4 million in 2022) capital. Another investment was in Knoxville, Tennessee, where he invested in a hotel, which was renamed the Lamar House Hotel, associated with the Bijou Theater.[4]

Around this time he became worried about his eldest son, Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar, whom he had appointed to look after his business affairs in Georgia. But the younger Lamar invested in The Wanderer, a ship used to smuggle in several hundred slaves in 1858 from the Congo to Jekyll Island, in violation of US law prohibiting the Atlantic slave trade. Four hundred survived the voyage and were sold in South Carolina and Georgia. Lamar and three other men were charged with slave trading, a capital offense. None of the defendants were convicted, as there were several hung juries and mistrials. However, Lamar and three other men were later arrested after trying to break another codefendant out of jail. They all later pleaded guilty to charges of attempting to rescue their. Each of them were sentenced to 30 days in jail and fined $250.[5]

Meanwhile, in New York, Lamar had become a valued contact for Southern state governments. The city's merchants and financiers had a long history of extensive relations with Southerners. Lamar arranged loans, printed bonds and, as the war neared, buying semi-obsolete rifles from the federal arsenal for the states of Georgia and South Carolina. At the start of the Civil War, his wife Harriet was in poor health. She died soon after the end of the war.

Lamar returned to Savannah by early 1861, where he was active in banking and re-established himself in the business and social life of the city. He was known to advise "representatives of the Confederate and Georgia governments, including President Jefferson Davis, Confederate Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger, and Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown".[2]

In the Spring of 1863, Lamar and nine other men announced the forming of the Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia.[6] They sponsored blockade runners to get products out and supplies in to support the Confederacy. while the blockade runners are considered critical to the Confederate war effort, they reached a peak relatively late in the war, when the Union blockade was getting stronger. While documenting it thoroughly, historian Stephen Wise describes the blockade running, like the Confederacy, as doomed.[7]

Through the blockade runners, Lamar continued to be active in the cotton trade. When Savannah fell, it is estimated that 10% of the cotton stores seized in the city by Union General Sherman belonged to Gazaway Lamar. The government held the cotton for later sale.

Postwar years

After the war ended, Lamar was arrested and held for three months as a suspect in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. During his time, his home was plundered by federal troops. After he was allowed to return to Savannah, he worked to re-establish his business and reclaim his confiscated cotton, which was held in warehouses in Georgia and Florida. He was arrested by the military occupation of the Reconstruction era on charges of "stealing government property and trying to bribe a government official." He was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison by a military commission. President Andrew Johnson overturned his conviction in 1869.

The U. S. Supreme Court had ruled in United States v. Padelford (1869) that the oath required by President Lincoln (known as the loyalty oath) was all that was needed for Southerners to receive compensation. Lamar continued to pursue compensation for his losses of cotton. Lamar was awarded $579,343.71 (~$13.6 million in 2022) in 1874 by the US Court of Claims in a settlement by the federal government for his losses. This was reported to be the largest individual settlement of the war, but was less than he had applied for.

Six months after winning his final appeal for compensation, Lamar died in Brooklyn, New York at age 76 on October 5, 1874. His body was returned to the home of his daughter Mrs. Robert Soutter in Alexandria, Virginia, where the funeral was held. Lamar was buried in that city. By his will, Lamar instructed his heirs to continue his claim for more compensation. They did so and were awarded another $75,000 (~$950,591 in 2022) in 1919.[8]

Early in the 21st century an old, rolled-up telegraph message was found and eventually given to a museum in Charleston, South Carolina. Dated April 14, 1861, the telegram was from the Governor of South Carolina to Gazaway Bugg Lamar in New York. Part of the message is below (for the complete text see "External Links", Fort Sumter telegram):

- "Fort Sumter surrendered yesterday after we had set all on fire... F.W. Pickens"

See also

References

- 1 2 Thomas Robson Hay, "Gazaway Bugg Lamar, Confederate Banker and Business Man", The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 2 (June, 1953), pp. 89–128, via JSTOR; accessed 31 January 2018

- 1 2 3 4 5 Biographical Note: Gazaway Bugg Lamar, Records Relating to Gazaway Bugg Lamar, National Archives at College Park, Maryland; accessed 31 January 2018

- ↑ SS Savannah and SS John Randolph, Savannah Historic Marker

- ↑ Dean Novelli, "On a Corner of Gay Street: A History of the Lamar House—Bijou Theater, Knoxville, Tennessee, 1817 – 1985", in East Tennessee Historical Society Publications (now Journal of East Tennessee History), Vol. 56 (1984), pp. 3–45.

- ↑ "The Clown Prince of Slavery". The Chiseler. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ↑ Mathis, Robert Neil, Gazaway Bugg Lamar, A Southern Entrepreneur, graduate dissertation, University of Georgia, 1968

- ↑ Stephen Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, University of South Carolina Press, 1988

- ↑ Biographical/Historical Note: G. B. Lamar papers, Library Univ. of Georgia

Further reading

- Thomas Robson Hay, "Gazaway Bugg Lamar, Confederate Banker and Business Man", The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 37, No. 2 (June, 1953), pp. 89–128, via JSTOR

- "Texas Naval Ship Zavala", National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA), non-profit website

- Thomas Lamar Coughlin, Those Southern Lamars (Xlibris: 2010), ISBN 0-7388-2410-0, self-published, real life stories but does not meet WP requirements as Reliable Source

External links

- "Biographical Note: Gazaway Bugg Lamar", Records Relating to Gazaway Bugg Lamar, National Archives at College Park, Maryland

- Biographical/Historical Note: G. B. Lamar papers, Library Univ. of Georgia

- Ft. Sumter telegram, Pickens to Lamar, 14 April 1861, Post and Courier, 13 April 2011

- "Papers donated to the Georgia Historical Society offer fresh insight to prominent Savannah native", SavannahNow.com, Savannah Morning News, 8 July 2011

- "SS Savannah" and "SS John Randolph", Savannah Historic Marker

- Lincoln's Oath, Freedmen website, University of Maryland

- "Importing and Exporting Company Stock certificates"