| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity."[1] Identified by the 2012 World Development Report as one of two key human capital endowments, health can influence an individual's ability to reach his or her full potential in society.[2] Yet while gender equality has made the most progress in areas such as education and labor force participation, health inequality between men and women continues to harm many societies to this day.

While both males and females face health disparities, women have historically experienced a disproportionate amount of health inequity. This stems from the fact that many cultural ideologies and practices have created a structured patriarchal society where women are vulnerable to abuse and mistreatment.[3] Additionally, women are typically restricted from receiving certain opportunities such as education and paid labor that can help improve their accessibility to better health care resources. Females are also frequently underrepresented or excluded from mixed-sex clinical trials and therefore subjected to physician bias in diagnosis and treatment. [3]

Definition of health disparity

Health disparity has been defined by WHO as the differences in health care received by different groups of people that are not only unnecessary and avoidable, but also unjust and prejudice.[4] The existence of health disparity implies that health equity does not exist in many parts of the world. Equity in health refers to the situation whereby every individual has a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential.[4] Overall, the term "health disparities", or "health inequalities", is widely understood as the differences in health between people who are situated in different positions in a socioeconomic hierarchy.[5]

Gender as an axis of difference

Bias against females

The social structures of many countries perpetuate the marginalization and oppression of women in the form of cultural norms and legal codes. As a result of this unequal social order, women are usually relegated into positions where they have less access and control over healthcare resources, making women more vulnerable to suffering from health problems than men. For example, women living in lower income areas have an acutely restricted protection of their health because they are less likely to have access to tertiary education and employment.[3] As a result, female life expectancy at birth, nutritional well-being, and immunity against communicable and non-communicable diseases, are often lower than those of men.[6][7]

Bias against males

While a majority of the global health gender disparities is weighted against women, there are situations in which men tend to fare poorer. One such instance is armed conflicts, where men are often the immediate victims. A study of conflicts in 13 countries from 1955 to 2002 found that 81% of all violent war deaths were male.[2] Apart from armed conflicts, areas with high incidence of violence, such as regions controlled by drug cartels, also see men experiencing higher mortality rates. This stems from social beliefs that associate ideals of masculinity with aggressive, confrontational behavior.[8] Lastly, sudden and drastic changes in economic environments and the loss of social safety nets, in particular social subsidies and food stamps, have also been linked to higher levels of alcohol consumption and psychological stress among men, leading to a spike in male mortality rates. This is because such situations often makes it harder for men to provide for their family, a task that has been long regarded as the "essence of masculinity."[9] A retrospective analyses of people infected with the common cold found that doctors underrate the symptoms of men, and are more willing to attribute symptoms and illness to women than men.[10] Women live longer than men in all countries, and across all age groups, for which reliable records exist.[11] In The United States, men are less healthy than women across all social classes. Non-white men are especially unhealthy. Men are over-represented in dangerous occupations and represent a majority of on the job deaths. Further, medical doctors provide men with less service, less advice, and spend less time with men than they do with women per medical encounter.[12]

Bias against intersex people

Another axis of health disparity is within the intersex community. Intersex, also known as disorders of sex development (DSD), is defined as "physical abnormalities of the sex organs"[13]

Intersex is often grouped into categories with the LGBT community. However, it is commonly mistaken that they are the same when they are not. Transgender persons are born with sex organs that do not match the gender they identify with, whereas intersex persons are born with sex organs or hormones that are neither clearly male nor female, often having to choose one gender to identify with.[14]

Healthcare of intersex persons is centered around what may be considered "cultural understandings of gender" or the binary system commonly used as gender.[15] Surgeries and other interventions are often used for intersex persons to attempt to physically change their body to conform with one sex. It has been debated whether or not this practice is ethical. Much of this pressure to choose one sex to conform to is socially implemented. Data suggest that children who do not have one gender to conform to may face embarrassment from peers.[16] Parents may also pressure their children to having cosmetic surgery to avoid being embarrassed themselves. Particular ethical concerns come into play when decisions are made on behalf of the child before they are old enough to consent.[17]

Intersex people can face discrimination when seeking healthcare. Laetitia Zeeman of University of Brighton, UK writes, "LGBTI people are more likely to experience health inequalities due to heteronormativity or heterosexism, minority stress, experiences of victimization and discrimination, compounded by stigma. Inequalities pertaining to LGBTI health(care) vary depending on gender, age, income and disability as well as between LGBTI groupings."[18] James Sherer of Rutgers University Medical School also found, "Many well-meaning and otherwise supportive healthcare providers feel uncomfortable when meeting an LGBT patient for the first time due to a general lack of knowledge about the community and the terminology used to discuss and describe its members. Common mistakes, such as incorrect language usage or neglecting to ask about sexual orientation and gender at all, may inadvertently alienate patients and compromise their care."[19]

Types of gender disparities

Male-female sex ratio

|

Countries with more females than males.

Countries with approximately the same number of males and females.

Countries with more males than females.

No data |

At birth, boys outnumber girls with the ratio of 105 or 106 male to 100 female children.[7] However, after conception, biology favors women. Research has shown that if men and women received similar nutrition, medical attention, and general health care, women would live longer than men.[20] This is because women, on a whole, are much more resistant to diseases and much less prone to debilitating genetic conditions.[21] However, despite medical and scientific research that shows that when given the same care as males, females tend to have better survival rates than males, the ratio of women to men in developing regions such as South Asia, West Asia, and China can be as low as 0.94, or even lower. This deviation from the natural male to female sex ratio has been described by Indian philosopher and economist Amartya Sen as the "missing women" phenomenon.[7] According to the 2012 World Development Report, the number of missing women is estimated to be about 1.5 million women per year, with a majority of the women missing in India and China.[2]

Female mortality

In many developing regions, women experience high levels of mortality.[22] Many of these deaths result from maternal mortality and HIV/AIDS infection. Although only 1,900 maternal deaths were recorded in high-income nations in 2008, India and Sub-Saharan Africa experienced a combined total of 266,000 deaths from pregnancy-related causes. In Somalia and Chad, one in every 14 women die from causes related to child birth.[2] However, some countries, such as Kenya, have made great strides by eliminating maternal and neonatal tetanus.[23]

In addition, the HIV/AIDS epidemic also contributes significantly to female mortality. The case is especially true for Sub-Saharan Africa, where women account for 60% of all adult HIV infections.[24]

Health outcome

Women tend to have poorer health outcomes than men for several reasons ranging from sustaining greater risk to diseases to experiencing higher mortality rates. In the Population Studies Center Research Report by Rachel Snow that compares the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) of both male and females, the global DALYs lost to females for sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea and chlamydia are more than ten times greater than those of the males.[25] Moreover, the female DALYs to male DALYs ratio for malnutrition-related diseases such as Iron-Deficiency Anemia are often close to 1.5, suggesting that poor nutrition impacts women at a much higher level than men.[25] Additionally, in terms of mental illnesses, women are also two to three times more likely than men to be diagnosed with depression.[26] With regards to suicidal rates, up to 80% of those who committed suicide or attempted suicide in Iran are women.[27]

In developed countries with more social and legal gender equality, overall health outcomes can disfavor men. For example, in the United States, as of 2001, men's life expectancy is 5 years lower than women's (down from 1 year in 1920), and men die at higher rates from all top 10 causes of death, especially heart disease and stroke.[28] Men die from suicide more frequently, though women more frequently have suicidal thoughts and the suicide attempt rate is the same for men and women (see Gender differences in suicide). Men may suffer from undiagnosed depression more frequently, due to gender differences in the expression of emotion.[29] American men are more likely to consume alcohol, smoke, engage in risky behaviors, and defer medical care.[30]

Incidence of melanoma has strong gender-related differences which vary by age.[31]

Women outlive men in 176 countries.[32] Data from 38 countries shows women having higher life expediencies than men for all years both at birth and at age 50. Men are more likely to die from 13 of the 15 major causes of death in the U.S. However, women are more likely to suffer from disease than men and miss work due to illness throughout life. This is called the mortality-morbidity paradox, or Health Survival paradox[33] This is explained by an excess of psychological, rather than physical, distress among women, as well as higher smoking rates among men.[34][35] Androgens also contribute to the male deficit in longevity.[36]

Access to healthcare

Women tend to have poorer access to health care resources than men. In certain regions of Africa, many women often lack access to malaria treatment as well as access to resources that could protect them against Anopheles mosquitoes during pregnancy.[37] As a result of this, pregnant women who are residing in areas with low levels of malaria transmission are still placed at two to three times higher risk than men in terms of contracting a severe malaria infection.[37] These disparities in access to healthcare are often compounded by cultural norms and expectations imposed on women. For example, certain societies forbid women from leaving their homes unaccompanied by a male relative, making it harder for women to receive healthcare services and resources when they need it most.[3]

Gender factors, such as women's status and empowerment (i.e., in education, employment, intimate partner relationships, and reproductive health), are linked with women's capacity to access and use maternal health services, a critical component of maternal health.[38] Still, family planning is typically viewed as the responsibility of women, with programs targeting women and overlooking the role of men—even though men's dominance in decision making, including contraceptive use, has significant implications for family planning[39] and access to reproductive health services.[40][41]

In order to promote equity in access to reproductive health care, health programs and services should conduct analyses to identify gender inequalities and barriers to health, and determine the programmatic implications. The analyses will help inform decisions about how to design, implement, and scale up health programs that meet the differential needs of women and men.[41][42]

Access to sexual and reproductive healthcare for men is important. Engaging men in sexual and reproductive health help to decrease their higher risk taking behaviors and increase gender equity. However, a scoping review in the Nordic countries have shown that men are facing difficulties in healthcare related to sexual and reproductive health.[43]

Causes

Cultural norms and practices

Cultural norms and practices are two of the main reasons why gender disparities in health exist and continue to persist. These cultural norms and practices often influence the roles and behaviors that men and women adopt in society. It is these gender differences between men and women, which are regarded and valued differently, that give rise to gender inequalities as they work to systematically empower one group and oppress the other. Both gender differences and gender inequalities can lead to disparities in health outcomes and access to health care. Some of the examples provided by the World Health Organization of how cultural norms can result in gender disparities in health include a woman's inability to travel alone, which can prevent them from receiving the necessary health care that they need.[44] Another societal standard is a woman's inability to insist on condom use by her spouse or sex partners, leading to a higher risk of contracting HIV.[44]

Son preference

One of the better documented cultural norms that augment gender disparities in health is the preference for sons.[45][46] In India, for instance, the 2001 census recorded only 93 girls per 100 boys. This is a sharp decline from 1961, when the number of girls per 100 boys was nearly 98.[3] In certain parts of India, such as Kangra and Rohtak the number of girls for every 100 boys can be as low as in the 70s.[47] Additionally, low female to male numbers have also been recorded in other Asian countries – most notably in China where, according to a survey in 2005, only 84 girls were born for every 100 boys. Although this was a slight increase from 81 during 2001–2004, it is still much lower than the 93 girls per 100 boys in the late 1980s.[3] The increasing number of unborn girls in the late 20th century has been attributed to technological advances that made pre-birth sex determination, also known as prenatal sex discernment, such as the ultrasound test more affordable and accessible to a wider population. This allowed parents who prefer a son to determine the sex of their unborn child during the early stages of pregnancy. By having early identification of their unborn child's sex, parents could practice sex-selective abortion, where they would abort the fetus if it was not the preferred sex, which in most cases is that of the female.[2]

Additionally, the culture of son preference also extends beyond birth in the form of preferential treatment of boys.[48] Economic benefits of having a son in countries like India also explain the preferential treatment of boys over girls. For example, in Indian culture it is the sons that provide care and economic stability to their parents as they age, so having a boy helps to ensure the futures of many Indian families.[49] This preferential care can be manifested in many ways, such as through differential provision of food resources, attention, and medical care. Data from household surveys over the past 20 years has indicated that the female disadvantage has persisted in India and may have even worsened in some other countries such as Nepal and Pakistan.[2]

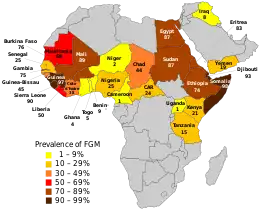

Female genital mutilation

Harmful cultural practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) also cause girls and women to face health risks. Millions of females are estimated to have undergone FGM, which involves partial or total removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. It is estimated that 92.5 million females over 10 years of age in Africa are living with the consequences of FGM. Of these, 12.5 million are girls between 10 and 14 years of age. Each year, about three million girls in Africa are subjected to FGM.[44]

Often performed by traditional practitioners using unsterile techniques and devices, FGM can have both immediate and late complications.[51][52] These include excessive bleeding, urinary tract infections, wound infection, and in the case of unsterile and reused instruments, hepatitis and HIV.[51] In the long run, scars and keloids can form, which can obstruct and damage the urinary and genital tracts.[51][52] According to a 2005 UNICEF report on FGM, it is unknown how many girls and women die from the procedure because of poor record keeping and a failure to report fatalities.[53] FGM may also complicate pregnancy and place women at a higher risk for obstetrical problems, such as prolonged labor.[51] According to a 2006 study by the WHO involving 28,393 women, neonatal mortality increases when women have experienced FGM; an additional ten to twenty babies were estimated to die per 1,000 deliveries.[54]

Psychological complications are related to cultural context. Women who undergo FGM might be emotionally affected when they move outside their traditional circles and are confronted with the view that mutilation is not the norm.[51]

Violence and abuse

Violence against women is a widespread global occurrence with serious public health implications. This is a result of social and gender bias.[55] Many societies in developing nations function on a patriarchal framework, where women are often viewed as a form of property and as socially inferior to men. This unequal standing in the social hierarchy has led women to be physically, emotionally, and sexually abused by men, both as children and adults. These abuses usually constitute some form of violence. Although children of both sexes do suffer from physical maltreatment, sexual abuse, and other forms of exploitation and violence, studies have indicated that young girls are far more likely than boys to experience sexual abuse. In a 2004 study on child abuse, 25.3% of all girls surveyed experienced some form of sexual abuse, a percentage that is three times higher than that of boys (8.7%).[56]

Such violence against women, especially sexual abuse, is increasingly being documented in areas experiencing armed conflicts. Presently, women and girls bear the brunt of social turmoil worldwide, making up an estimated 65% of the millions who are displaced and affected.[57] Some of these places which are facing such problems include Rwanda, Kosovo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[57] This comes as a result of both the general instability around the region, as well as a tactic of warfare to intimidate enemies. Often being placed in emergency and refugee settings, girls and women alike are highly vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by military combatants, security forces, and members of rival communities.[56]

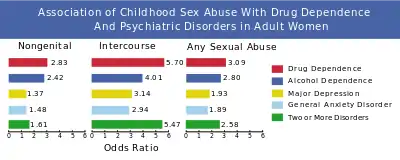

The sexual violence and abuse of both young and adult women have both short and long-term consequences, contributing significantly to a myriad of health issues into adulthood. These range from debilitating physical injuries, reproductive health issues, substance abuse, and psychological trauma. Examples of the above categories include depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol and drug use and dependence, sexually transmitted diseases, lower frequency of certain types of health screenings (such as cervical cancer),[58] and suicide attempts.[57]

Abused women often have higher rates of unplanned and problematic pregnancies, abortions, neonatal and infant health issues, sexually transmitted infections (including HIV), and mental disorders (such as depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders and eating disorders) as compared to their non-abused peers.[2] During peacetime, most violence against women is perpetrated by either male individuals whom them know or intimate male partners. An eleven-country study conducted by WHO between 2000 and 2003 found that, depending on the country, between 15% and 71% of women have experienced physical or sexual violence by a husband or partner in their lifetime, and 4% to 54% within the previous year.[59] Partner violence may also be fatal. Studies from Australia, Canada, Israel, South Africa and the United States show that between 40% and 70% of female murders were carried out by intimate partners.[60]

Other forms of violence against women include sexual harassment and abuse by authority figures (such as teachers, police officers or employers), trafficking for forced labour or sex, and traditional practices such as forced child marriages and dowry-related violence. At its most extreme, violence against women can result in female infanticide and violent death. Despite the size of the problem, many women do not report their experience of abuse and do not seek help. As a result, violence against women remains a hidden problem with great human and health care costs.[55] Worldwide men account for 79% of all victims of homicide. Homicide statistics by gender

Poverty

Poverty is another factor that facilitates the continual existence of gender disparities in health.[2] Poverty is often directly linked with poor health.[61] However, indirectly it affects factors such as lack of education, resources, and transportation that have the potential to contribute to poor health.[61] In addition to economic constraints, there are also cultural constraints that affect people's ability or likelihood to enter a medical setting. While gender disparities continue prevalent in health, the extent to which it occurs within poor communities often depends on factors like the socioeconomic state of their location, cultural differences and even age.

Children living in poverty have limited access to basic health needs overall, however gender inequalities become more apparent as children age. Research done on children under the age of five suggests that in low to middle income countries, approximately 50% of children living in poverty had access to basic health care.[62] There was also no significant difference between boys and girls in access to healthcare services, such as immunizations and treatment for prevalent diseases such as malaria for both.[62] Research focused on a wider age range, from infancy to adolescence, showed different results. It was found that in developing countries girls had more limited access to care, and if accessed they were likely to receive inferior care to that of boys.[63][64] Girls in developing countries were also found to be more likely to suffer emotional and physical abuse inflicted by their family and community.[63]

Gender inequalities in health for those living in poverty continue into adulthood. In research that excluded women's health disadvantages (childbirth, pregnancy, susceptibility to HIV, etc.) it was found that there was not a significant gender difference in diagnosis and treatment of chronic conditions.[62] In fact, women were diagnosed more, which was attributed to the fact that women had more access to healthcare due to reproductive needs, or from taking their children in for checkups.[62] By contrast, research that was inclusive of women's health disadvantages revealed that maternal health widened the gap between men and women's health. Poor women in underdeveloped countries were said to be at greater risk of disability and death.[63] The lack of resources and proper nourishment is often a cause of death, and contributes to issues of preterm birth and infant mortality, as well as a contributor to maternal mortality.[65][64] It is estimated that about 800 women die daily from maternal mortality, and most cases are preventable. However, 99% of the cases occur in poverty ridden regions that lack the resources to access prompt, as well as preventive medical care.[65]

The gendered health differences were slightly different for people living in poverty in wealthier countries. Women were reported to be more low-income than men, and more likely to forgo medical treatment due to financial circumstances.[66] In the United States the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) made it more possible for more people living in poverty to have access to healthcare, especially for women, however it is argued that the Act also promotes gender inequality because of differences in coverage.[66] Gender- specific cancer screenings, such as for prostate cancer is not covered for men, while similar screenings for women are.[66] At the same time, screenings such as counseling and other services for intimate partner violence is covered for women and not for men.[66] In European countries the results were different than those of people in the United States. While in the United States poor men had less quality healthcare than women, in European countries men had less access to healthcare. The studies revealed that people, of age 50 and over, who struggled to make ends meet (subjective poverty) were 38% more likely to decline in health than those who were considered low income or had low overall wealth.[61] However, men with subjective poverty of the same age group were 65% more likely to die than women, within a 3 to 6-year period.[61]

Healthcare system

The World Health Organization defines health systems as "all the activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health".[67] However, factors outside of healthcare systems can influence the impact healthcare systems have on the health of different demographics within a population. This is because healthcare systems are known to be influenced by social, cultural and economic frameworks. As a result, health systems are regarded as not only "producers of health and health care", but also as "purveyors of a wider set of societal norms and values," many of which are biased against women[68]

In the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network's Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2007, health systems in many countries were noted to have been unable to deliver adequately on gender equity in health. One explanation for this issue is that many healthcare systems tend to neglect the fact that men and women's health needs can be very different.[69] In the report, studies have found evidence that the healthcare system can promote gender disparities in health through the lack of gender equity in terms of the way women are regarded – as both consumers (users) and producers (carers) of health care services.[69] For instance, healthcare systems tend to regard women as objects rather than subjects, where services are often provided to women as a means of something else rather on the well-being of women.[69] In the case of reproductive health services, these services are often provided as a form of fertility control rather than as care for women's well-being.[70] Additionally, although the majority of the workforce in health care systems are female, many of the working conditions remain discriminatory towards women. Many studies have shown that women are often expected to conform to male work models that ignore their special needs, such as childcare or protection from violence.[71] This significantly reduces the ability and efficiency of female caregivers providing care to patients, particularly female ones.[72][73]

Structural gender oppression

Structural gender inequalities in the allocation of resources, such as income, education, health care, nutrition and political voice, are strongly associated with poor health and reduced well-being. Very often, such structural gender discrimination of women in many other areas has an indirect impact on women's health. For example, because women in many developing nations are less likely to be part of the formal labor market, they often lack access to job security and the benefits of social protection, including access to health care. Additionally, within the formal workforce, women often face challenges related to their lower status, where they suffer workplace discrimination and sexual harassment. Studies have shown that this expectation of having to balance the demands of paid work and work at home often give rise to work-related fatigue, infections, mental ill-health and other problems, which results in women faring poorer in health.[74]

Women's health is also put at a higher level of risk as a result of being confined to certain traditional responsibilities, such as cooking and water collection. Being confined to unpaid domestic labor not only reduces women's opportunities to education and formal job employment (both of which can indirectly contribute to better health in the long run), but also potentially expose women to higher risk of health issues. For instance, in developing regions where solid fuels are used for cooking, women are exposed to a higher level of indoor air pollution due to extended periods of cooking and preparing meals for the family. Breathing air tainted by the burning of solid fuels is estimated to be responsible for 641,000 of the 1.3 million deaths of women worldwide each year due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD).[75]

In some settings, structural gender inequity is associated with particular forms of violence, marginalization, and oppression against females. This includes violent assault by men, child sexual abuse, strict regulation of women's behavior and movement, female genital mutilation, and exploitative, forced labor.[3] Women and girls are also vulnerable to less well-documented forms of abuse or exploitation, such as human trafficking or "honor killings" for perceived behavioral transgressions and deviation of their social roles. These acts are associated with a wide range of health problems in women such as physical injuries, unwanted pregnancies, abortions, mental disorders such as depression, and anxiety, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted infections, all of which can potentially lead to premature death.[76][77]

The ability of women to utilize health care is also heavily influenced by other forms of structural gender inequalities. These include unequal restriction on one's mobility and behavior, as well as unequal control over financial resources. Many of these social gender inequalities can impact the way women's health is regarded, which can in turn determine the level of access women have to healthcare services and the extent by which households and the larger community are willing to invest in women's health issues.[69]

Other axes of oppression

Apart from gender discrimination, other axes of oppression also exist in society to further marginalize certain groups of women, especially those who are living in poverty or of minority status in which they live.[3]

Race and ethnicity

Race is a well known axis of oppression, where people of color tend to suffer more from structural violence. For people of color, race can serve as a factor, in addition to gender, that can further influence one's health negatively.[78] Studies have shown that in both high-income and low-income countries, levels of maternal mortality may be up to three times higher among women of disadvantaged ethnic groups than among white women. In a study on race and mother-death within the US, the maternal mortality rate for African Americans is close to four times higher than that of white women. Similarly in South Africa, the maternal mortality rate for black/African women and women of color is approximately 10 and 5 times greater respectively than that of white/European women.[79]

Socioeconomic status

Although women around the world share many similarities in terms of the health-impacting challenges, there are also many distinct differences that arise from their varying states of socioeconomic conditions. The type of living conditions in which women live is largely associated with not only their own socioeconomic status, but also that of their nation.[3]

At every single age category, women in high income countries tend to live longer and are less likely to suffer from ill health than and premature mortality than those in low income countries. Death rates in high-income countries are also very low among children and younger women, where most deaths occur after the age of 60 years. In low-income countries however, the death rates at young ages are much higher, with most death occurring among girls, adolescents, and younger adult women. Data from 66 developing countries show that child mortality rates among the poorest 20% of the population are almost double those in the top 20%. [80] The most striking health outcome difference between rich and poor countries is maternal mortality. Presently, an overwhelming proportion of maternal mortality is concentrated within the nations that are suffering from poverty or some other form of humanitarian crises, where 99% of the more than half a million maternal deaths every year occur. This comes from the fact that institutional structures which could protect women's health and well-being are either lacking or poorly developed in these places.[3]

The situation is similar within countries as well, where the health of both girls and women is critically affected by social and economic factors. Those who are living in poverty or of lower socioeconomic status tend to perform poorly in terms of health outcomes. In almost all countries, girls and women living in wealthier households experience lower levels of mortality and higher usage of health care services than those living in the poorer households. Such socioeconomic status-related health disparities is present in every nation around the world, including developed regions.[3]

Environmental Injustice

Environmental injustice at its core is the presence of distributional injustice including both the distribution of decision-making power as well as the distribution of environmental burden. Environmental burdens, which include water pollution, toxic chemicals, etc., can disproportionately impact the health of women.[81] Women are often left out of policy making and decisions. These injustices occur because women are generally affected by intersectionality of oppression which leads to lower incomes and less social status.[81] Root causes of these injustices is the fundamental presence of gender inequality, particularly in marginalized communities (Indigenous women, women from low-income communities, women from the Global South, etc.) that will become amplified by climate change.[82][83] These women are often reliant on natural resources for their livelihoods and, therefore, are one of the first groups of people to be severely impacted by global climate change and environmental injustice.[84] In addition, women all around the world are held responsible for providing food, water, and care to their families.[84] This has sparked a movement to make the literature, research, and teaching more gender aware in the sphere of feminism.[81]

However, women continue to face oppression in the sphere of media. CNN and Media Matters have reported that only 15% of those interviewed in the media on climate change have been women.[85] Comparatively, women make up 90% of environmental justice groups across the United States.[82] UN climate chief Christiana Figueres has publicly recognized gender disparity in environmental injustice and has pledged to put gender at the center of the Paris talks on climate change. "Women are disproportionately affected by climate change. It is increasingly evident that involving women and men in all decision-making on climate action is a significant factor in meeting the climate challenge".[86] Studies have shown that women's involvement and participation in policy leadership and decision-making has led to a greater increase in conservation and climate change mitigation efforts.

When we analyze root causes, it is clear that women experience climate change with disproportionate severity precisely because their basic rights continue to be denied in varying forms and intensities across the world.[84] Enforced gender inequality reduces women's physical and economic mobility, voice, and opportunity in many places, making them more vulnerable to mounting environmental stresses. Indigenous pregnant women and their unborn children are more vulnerable to climate change and health impacts by way of environmental injustice.[87] Indigenous women, women from low-income communities, and women from the Global South bear an even heavier burden from the impacts of climate change because of the historic and continuing impacts of colonialism, racism and inequality; and in many cases, because they are more reliant upon natural resources for their survival and/or live in areas that have poor infrastructure.[83] Drought, flooding, and unpredictable and extreme weather patterns present life or death challenges for many women, who are most often the ones responsible for providing food, water and energy for their families.[82]

Gender bias in clinical trials

Gender bias is prevalent in medical research and diagnosis. Historically, women were excluded from clinical trials, which affects research and diagnosis. Throughout clinical trials, Caucasian males were the normal test subjects and findings were then generalized to other populations.[88] Women were considered more expensive and complicated clinical trial subjects because of variable hormone levels that differ significantly from men's.[88] Specifically, pregnant women were considered an at-risk population and thus barred from participation in any clinical trials.[88]

In 1993, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published "Guidelines for the Study and Evaluation of Gender Differences in the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs", overwriting the 1977 decision to bar all pregnant women from clinical trials.[88] Through this, they recommended that women be included in clinical trials to explore differences in the sexes, specifying that the population included in clinical trials should be indicative of the population to whom the drug would be prescribed.[88] This mandated the inclusion of female participants in clinical trials sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).[88] The FDA's 1998 "Presentation of Safety and Effectiveness Data for Certain Subgroups of the Population in Investigational New Drug Application Reports and New Drug Applications" regulations mandated that drug trials prove safety and efficacy in both sexes in order to gain FDA approval and led to drugs being taken off the market due to adverse affects on women that had not been appropriately studied during clinical trials.[88] Several more recent studies determined in hindsight that many federally funded studies from 2009 included a higher percentage of female participants but did not include findings specified between males and females.[89]

In 1994, the FDA established an Office of Women's Health, which promotes that sex as a biological variable should be explicitly considered in research studies.[90] The FDA and NIH have several ongoing formal efforts to improve the study of sex differences in clinical trials, including the Critical Path Initiative, which uses biomarkers, advanced technologies, and new trial designs to better analyze subgroups.[91][92] Another initiative, Drug Trial Snapshots, offers transparency to subgroup analysis via a consumer-focused website.[88][93] However, despite such work, women are less likely to be aware of or to participate in clinical trials.[88]

Although inclusion of women in clinical trials is now mandated, there is no such mandate for use of female animal models in non-human research.[94] Typically, male models are used in non-human research and results are generalized to females.[94] This can complicate diagnosis. A 2011 review article examined sex bias in biomedical research and found that while sex bias has decreased in human clinical trials, particularly since the US National Institute of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, sex bias has increased in non-human studies.[94] Additionally, studies often fail to analyze results by sex specifically.[94] Another example of this is the thalidomide epidemic. In the late 1950s thalidomide was prescribed to pregnant women to treat morning sickness. Its use unexpectedly resulted in severe birth defects in over 10,000 children.[95] However, proper studies were not conducted to determine adverse effects in women, specifically those who are pregnant and it was determined that mice, the animal model used to test thalidomide, were less sensitive to it than humans.[96]

Gender bias in diagnosis

A 2018 literature review of 77 medical articles found gender bias in the patient-provider encounter as it related to pain. Their findings confirmed a pattern of expectations and treatment differences between men and women, "not embedded in biological differences but gendered norms."[97] For example, women with pain were viewed as "hysterical, emotional, complaining, not wanting to get better, malingerers, and fabricating the pain, as if it is all in her head."[97] Women suffering with chronic pain are often erroneously attributed psychological rather than somatic causes for their pain by physicians.[97] And in searching for the effect on pain medication given to men and women, studies determined that women received less effective pain relief, less opioid pain medication, more antidepressants, and more psychiatric referrals.[97]

Management

The Fourth World Conference on Women asserts that men and women share the same right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.[98] However, women are disadvantaged due to social, cultural, political and economic factors that directly influence their health and impede their access to health-related information and care.[3] In the 2008 World Health Report, the World Health Organization stressed that strategies to improve women's health must take full account of the underlying determinants of health, particularly gender inequality. Additionally, specific socioeconomic and cultural barriers that hamper women in protecting and improving their health must also be addressed.[99]

Gender mainstreaming

Gender mainstreaming was established as a major global strategy for the promotion of gender equality in the Beijing Platform for Action from the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.[100] Gender mainstreaming is defined by the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 1997 as follows:

"Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate aim is to achieve gender equality".[100]

Over the past few years, "gender mainstreaming" has become a preferred approach for achieving greater health parity between men and women. It stems from the recognition that while technical strategies are necessary, they are not sufficient in alleviating gender disparities in health unless the gender discrimination, bias and inequality that in organizational structures of governments and organizations – including health systems – are being challenged and addressed.[3] The gender mainstreaming approach is a response to the realisation that gender concerns must be dealt with in every aspect of policy development and programming, through systematic gender analyses and the implementation of actions that address the balance of power and the distribution of resources between women and men.[101] In order to address gender health disparities, gender mainstreaming in health employs a dual focus. First, it seeks to identify and address gender-based differences and inequalities in all health initiatives; and second, it works to implement initiatives that address women's specific health needs that are a result either of biological differences between women and men (e.g. maternal health) or of gender-based discrimination in society (e.g. gender-based violence; poor access to health services).[102]

Sweden's new public health policy, which came into force in 2003, has been identified as a key example of mainstreaming gender in health policies. According to the World Health Organization, Sweden's public health policy is designed to address not only the broader social determinants of health, but also the way in which gender is woven into the public health strategy.[102][103][104] The policy specifically highlights its commitment to address and reduce gender-based inequalities in health.[105]

Female Empowerment

The United Nations has identified the enhancement of women's involvement as way to achieve gender equality in the realm of education, work, and health.[106] This is because women play critical roles as caregivers, formally and informally, in both the household and the larger community. Within the United States, an estimated 66% of all caregivers are female, with one-third of all female caregivers taking care of two or more people[107] According to the World Health Organization, it is important that approaches and frameworks that are being implemented to address gender disparities in health acknowledge the fact that majority of the care work is provided by women.[3] A meta-analysis of 40 different women's empowerment projects found that increased female participation have led to a broad range of quality of life improvements. These improvements include increases in women's advocacy demands and organization strengths, women-centered policy and governmental changes, and improved economic conditions for lower class women.[108]

In Nepal, a community-based participatory intervention to identify local birthing problems and formulating strategies has been shown to be effective in reducing both neonatal and maternal mortality in a rural population.[109] Community-based programs in Malaysia and Sri Lanka that used well-trained midwives as front-line health workers also produced rapid declines in maternal mortality.[110]

International states of gender disparities in health

South-East Asia region[111]

Women in South-East Asia often find themselves in subordinate positions of power and dependency on their male counterparts-regarding cultural, economics, and societal relations. Because there is a limited level of control and access granted to women in this region, the capability for daughters to counteract generational biases regarding gender specific roles are highly limited. In contrast to many other industrialised countries, life expectancy is equal or shorter for women in this region, with the probability of surviving the first five years of life for women equal to or smaller than that of males.

A potential explanation as to why there are disparate difference in health status and access between genders is due to an unbalanced sex ratio-for example, the Indian subcontinent has a ratio of 770 women per 1000 men. Neglect of female children, limited or poor access to health care, sex selective abortions, and reproductive mortality are all additional reasons as to why there is a severe inequity between genders. Education and increased socioeconomical independency are projected to assist in the leveling of health-care access between the genders, but there are sociocultural circumstances and attitudes concerning the prioritization of males over females that stagnates progress. Sri Lanka has repeatedly been identified as a role model of sorts for other nations within this region, as there are minimal differences in health, educational, and employment levels between genders.

European Region[112]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) gender discrimination in relation to lack of access and provision of health in this region is supported by concrete survey data. In the European Region, 1 in 5 women have been domestic violence victims, while honour killings, female genital mutilation, and bride kidnapping still occur. Additional studies done by the WHO have found that immigrant women face a 43% higher risk of having an underweight child, 61% greater risk of having a child with congenital malformations, and 50% higher chance of perinatal mortality. In European countries, women make up the majority of those unemployed, earning an average 15% less than men while 58% were observed to be unemployed. Differences in wages are even greater in the Eastern part of the region, as represented in the comparison of wages between women (4954 US dollars) in Albania versus men (9143 US dollars.)

Eastern Mediterranean Region[113]

Access to education and employment are key elements in achieving gender equality in health. Female literacy rates in the Eastern Mediterranean were found by the WHO to fall sharply behind their male counterparts, as evident in the cases of Yemen (66:100) and Djibouti (62:100.) Further barriers other than the prioritization of providing opportunities for males, include the inability for females in this region to pursue anything more than a tertiary education because of economic constraints. Contraceptive usage and knowledge of reproductive options were found to be more present amongst women who had received higher levels of education in Egypt, the rate of contraceptive usage being 93% among those who were university-educated versus illiterate.

In regards to the influence of employment upon a woman's capability to know of and fight for equity in health care, in this region, women were found by the WHO to participate lower in the labor market than other regions (at an average of 28%.) The lowest number of women in paid employment within this region was found in Saudi Arabia and other countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), while the highest number of women with paid employment were in Morocco, Lebanon, and Yemen.

The lack of availability of health care services in this region particularly complicates matters as certain countries are already strained by ongoing conflict and war. According to WHO, the ratio of physicians per population is drastically lower in the countries Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and Djibouti, while health infrastructures are nearly nonexistent in Afghanistan. With additional complications of distance to and from medical services, the access of health care services is even more complex for women in this region as the majority are unable to afford the transportation costs or time.

Western Pacific Region[114]

Gender based division of labor in this region has been observed by the WHO as reason for the differences in health risks that the two genders are exposed to in contrast to one another. Most commonly, women of this region are engaged in insecure and informal forms of labor, therefore being unable to gain related benefits such as insurance or pension. In regards to education, the gap between male and females is relatively small in primary and secondary schools, however, there is undeniably an uneven distribution of literacy rates between the various countries within this region. According to the WHO substantial differences in literacy rates between men and women exist particularly in Papua New Guinea (55.6% for women and 63.6% for men) and Lao People's Democratic Republic (63.2% for women and 82.5% for men.)

See also

References

- ↑ World Health Organization (2006). Constitution of the World Health Organization – Basic Documents, Forty-fifth edition (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The World Bank (2012). World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development (Report). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 World Health Organization (2009). Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda (PDF) (Report). WHO Press. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- 1 2 Whitehead, M (1990). The Concepts and Principles of Equity in Health (PDF) (Report). Copenhagen: WHO, Reg. Off. Eur. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Braveman, P. (2006). "Health Disparities and Health Equity: Concepts and Measurement". Annual Review of Public Health. 27: 167–194. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. PMID 16533114.

- ↑ Vlassoff, C (March 2007). "Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 25 (1): 47–61. PMC 3013263. PMID 17615903.

- 1 2 3 Sen, Amartya (1990). "More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing". New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Márquez, Patricia (1999). The Street Is My Home: Youth and Violence in Caracas. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Brainerd, Elizabeth; Cutler, David (2005). "Autopsy on an Empire: Understanding Mortality in Russia and the Former Soviet Union". Ann Arbor, MI: William Davidson Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Sue, Kyle (2017). "The science behind 'man flu.'" (PDF). BMJ. 359: j5560. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5560. PMID 29229663. S2CID 3381640. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ↑ Austad, S.N.A; Bartke, A.A. (2016). "Sex Differences in Longevity and in Responses to Anti-Aging Interventions: A Mini-Review". Gerontology. 62 (1): 40–6. doi:10.1159/000381472. PMID 25968226.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (May 2003). "The Health of Men: Structured Inequalities and Opportunities". Am J Public Health. 93 (5): 724–731. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. PMC 1447828. PMID 12721133.

- ↑ Kraus, Cynthia (1 July 2015). "Classifying Intersex in DSM-5: Critical Reflections on Gender Dysphoria" (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 44 (5): 1147–1163. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0550-0. ISSN 1573-2800. PMID 25944182. S2CID 24390697.

- ↑ Greenberg, Julie; Herald, Marybeth; Strasser, Mark (1 January 2010). "Beyond the Binary: What Can Feminists Learn from Intersex Transgender Jurisprudence". Michigan Journal of Gender & Law. 17 (1): 13–37. ISSN 1095-8835.

- ↑ Kessler, Suzanne J. (1990). "The Medical Construction of Gender: Case Management of Intersexed Infants". Signs. 16 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1086/494643. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 3174605. S2CID 33122825.

- ↑ Newbould, Melanie (2016). "When Parents Choose Gender: Intersex, Children, and the Law". Medical Law Review. 24 (4): 474–496. doi:10.1093/medlaw/fww014. ISSN 1464-3790. PMID 28057709.

- ↑ Roen, Katrina (20 October 2004). "Intersex embodiment: when health care means maintaining binary sexes". Sexual Health. 1 (3): 127–130. doi:10.1071/SH04007. ISSN 1449-8987. PMID 16335298.

- ↑ Zeeman, Laetitia; Sherriff, Nigel; Browne, Kath; McGlynn, Nick; Mirandola, Massimo; Gios, Lorenzo; Davis, Ruth; Sanchez-Lambert, Juliette; Aujean, Sophie; Pinto, Nuno; Farinella, Francesco (1 October 2019). "A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) health and healthcare inequalities". European Journal of Public Health. 29 (5): 974–980. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky226. ISSN 1101-1262. PMC 6761838. PMID 30380045.

- ↑ Sherer, James; Levounis, Petros (2020), Marienfeld, Carla (ed.), "LGBTQIA: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual or Allied", Absolute Addiction Psychiatry Review: An Essential Board Exam Study Guide, Springer International Publishing, pp. 277–287, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33404-8_17, ISBN 978-3-030-33404-8, S2CID 216398742

- ↑ Dennerstein, L; Feldman, S; Murdaugh, C; Rossouw, J; Tennstedt, S (1977). 1997 World Congress of Gerontology: Ageing Beyond 2000 : One World One Future. Adelaide: International Association of Gerontology.

- ↑ Huang, Audrey. "X chromosomes key to sex differences in health". JAMA and Archives Journals. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Prata, Ndola; Passano, Paige; Sreenivas, Amita; Gerdts, Caitlin Elisabeth (1 March 2010). "Maternal mortality in developing countries: challenges in scaling-up priority interventions". Women's Health. 6 (2): 311–327. doi:10.2217/WHE.10.8. PMID 20187734.

- ↑ Dutta, Tapati; Agley, Jon; Lin, Hsien-Chang; Xiao, Yunyu (1 May 2021). "Gender-responsive language in the National Policy Guidelines for Immunization in Kenya and changes in prevalence of tetanus vaccination among women, 2008–09 to 2014: A mixed methods study". Women's Studies International Forum. 86: 102476. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102476. ISSN 0277-5395.

- ↑ UNAIDS (2010). "Women, Girls, and HIV" UNAIDS Factsheet 10 (Report). Geneva: UNAIDS.

- 1 2 Rachel Snow (2007). Population Studies Center Research Report 07-628: Sex, Gender and Vulnerability (PDF) (Report). Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research.

- ↑ Usten, T; Ayuso-Mateos, J; Chatterji, S; Mathers, C; Murray, C (2004). "Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000". Br J Psychiatry. 184 (5): 386–92. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.5.386. PMID 15123501.

- ↑ Mohammadi, M. R.; Ghanizadeh, A.; Rahgozart, M.; Noorbala, A. A.; Malekafzali, H.; Davidian, H.; Naghavi, H.; Soori, H.; Yazdi, S. A. (2005). "Suicidal Attempt and Psychiatric Disorders in Iran". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 35 (3): 309–316. doi:10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.309. PMID 16156491.

- ↑ "Men's Top 5 Health Concerns".

- ↑ "Men's Top 5 Health Concerns".

- ↑ "Men's Health".

- ↑ "Skin cancer".

- ↑ "Women outliving men 'everywhere', new UN health agency statistics report shows". UN News. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ↑ Austad, Kathleen E.; Fischer, Steven N. (2016). "Sex Differences in Lifespan". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 1022–1033 [1026–28]. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.019. PMC 4932837. PMID 27304504.

- ↑ Macintyre, Sally; Hunt, Kate; Sweeting, Helen (1996). "Gender differences in health: Are things really as simple as they seem?". Social Science & Medicine. 42 (4): 617–624. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00335-5. PMID 8643986.

- ↑ Case, Anne. Paxson, Christina. "Sex Differences in Morbidity and Mortality." Demography, Volume 42-Number 2, May 2005: 189–214. http://ai2-s2-pdfs.s3.amazonaws.com/8838/5ed24cb4148de6362e9ba157b3c00b51d449.pdf.

- ↑ Gems, D (2014). "Evolution of sexually dimorphic longevity in humans". Aging (Albany NY). 6 (2): 84–91. doi:10.18632/aging.100640. PMC 3969277. PMID 24566422.

- 1 2 WHO/UNICEF (2003). The Africa Malaria Report 2003 (Report). Geneva: WHO/UNICEF.

- ↑ Gill, R; Stewart, DE (2011). "Relevance of gender-sensitive policies and general health indicators to compare the status of South Asian women's health". Women's Health Issues. 21 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.003. PMID 21185987.

- ↑ Schuler, S.; Rottach, E.; Mukiri, P. (2011). "Gender Norms and Family Planning Decision-Making in Tanzania: A Qualitative Study". Journal of Public Health in Africa. 2 (2): 2. doi:10.4081/jphia.2011.e25. PMC 5345498. PMID 28299066.

- ↑ Hou, X., and N. Ma. 2011. "Empowering Women: The Effect of Women's Decision-Making Power on Reproductive Health Services Uptake—Evidence from Pakistan." World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5543.

- 1 2 Rottach, E., K. Hardee, R. Jolivet, and R. Kiesel. 2012. "Integrating Gender into the Scale-Up of Family Planning and Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health Programs." Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project.

- ↑ Rottach, E. 2013. "Approach for Promoting and Measuring Gender Equality in the Scale-Up of Family Planning and Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health Programs." Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project.

- ↑ Baroudi, Mazen; Stoor, Jon Petter; Blåhed, Hanna; Edin, Kerstin; Hurtig, Anna-Karin (2021). "Men and sexual and reproductive healthcare in the Nordic countries: A scoping review". BMJ Open. 11 (9): e052600. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052600. PMC 8487177. PMID 34593504.

- 1 2 3 "Gender, Women, and Health". WHO. Archived from the original on 10 November 2004. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Edlund, Lena (1 December 1999). "Son Preference, Sex Ratios, and Marriage Patterns". Journal of Political Economy. 107 (6, Part 1): 1275–1304. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.5921. doi:10.1086/250097. S2CID 38412584.

- ↑ Das Gupta, Monica; Zhenghua, Jiang; Bohua, Li; Zhenming, Xie; Chung, Woojin; Hwa-Ok, Bae (1 December 2003). "Why is Son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? a cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea" (PDF). Journal of Development Studies. 40 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1080/00220380412331293807. S2CID 17391227.

- ↑ John, Mary E.; Kaur, Ravinder; Palriwala, Rajni; Raju, Saraswati; Sagar, Alpana (2008). Disappearing Daughters (PDF) (Report). London, UK: ActionAid. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Arnold, Fred; Choe, Minja Kim; Roy, T.K. (1 November 1998). "Son Preference, the Family-building Process and Child Mortality in India". Population Studies. 52 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150486.

- ↑ Rosenblum, Daniel (15 July 2016). "Estimating the Private Economic Benefits of Sons Versus Daughters in India". Feminist Economics. 23 (1): 77–107. doi:10.1080/13545701.2016.1195004. ISSN 1354-5701. S2CID 156163393.

- ↑ "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Global Concern" (PDF). New York: United Nations Children's Fund. February 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abdulcadir, J; Margairaz, C; Boulvain, M; Irion, O (6 January 2011). "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting". Swiss Medical Weekly. 140: w13137. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13137. PMID 21213149.

- 1 2 Kelly, Elizabeth; Hillard, Paula J Adams (1 October 2005). "Female genital mutilation". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 17 (5): 490–494. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000183528.18728.57. PMID 16141763. S2CID 7706452.

- ↑ UNICEF (2005). Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (Report). Florence, Italy: Innocenti Digest/UNICEF.

- ↑ Banks, E; Meirik, O; Farley, T; Akande, O; Bathija, H; Ali, M (1 June 2006). "Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1835–1841. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. PMID 16753486. S2CID 1077505.

- 1 2 "Violence and injuries to/against women". WHO. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- 1 2 Ezzati, M; Lopez, A; Rodgers, A; Murray, C (2004). "Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors". Geneva: World Health Organization.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Garcia-Moreno, C; Reis, C (2005). "Overview on women's health in crises" (PDF). Health in Emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization (20).

- ↑ Dutta, Tapati (2018). "Association Between Individual and Intimate Partner Factors and Cervical Cancer Screening in Kenya". Preventing Chronic Disease. 15: E157. doi:10.5888/pcd15.180182. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 6307831. PMID 30576277.

- ↑ Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H. A. M.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C. H. (2006). "Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence". The Lancet. 368 (9543): 1260–1269. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. PMID 17027732. S2CID 18845439.

- ↑ Krug, E (2002). World report on violence and health (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 1 2 3 4 Adena, Maja; Myck, Michal (September 2014). "Poverty and transitions in health in later life". Social Science & Medicine. 116: 202–210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.045. PMID 25042393.

- 1 2 3 4 Wagner, Anita K.; Graves, Amy J.; Fan, Zhengyu; Walker, Saul; Zhang, Fang; Ross-Degnan, Dennis (March 2013). "Need for and Access to Health Care and Medicines: Are There Gender Inequities?". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57228. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857228W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057228. PMC 3591435. PMID 23505420.

- 1 2 3 Cesario, Sandra K.; Moran, Barbara (May–June 2017). "Empowering the Girl Child, Improving Global Health". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 46 (3): e65–e74. doi:10.1016/j.jogn.2016.08.014. PMID 28285003. S2CID 206336887.

- 1 2 Tyer-Viola, Lynda A.; Cesario, Sandra K. (July 2010). "Addressing Poverty, Education, and Gender Equality to Improve the Health of Women Worldwide". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 39 (5): 580–589. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01165.x. PMID 20673314.

- 1 2 Nour, N. M. (2014). "Global Women's Health: Progress toward Reducing Sex-Based Health Disparities". Clinical Chemistry. 60 (1): 147–150. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2013.213181. PMID 24046203.

- 1 2 3 4 Veith, Megan (Spring 2014). "The Continuing Gender-Health Divide: A Discussion of Free Choice, Gender Discrimination, and Gender Theory as Applied to the Affordable Care Act".

- ↑ World Health Organization (2001). World Health Report 2001 (PDF) (Report). Geneva.

- 1 2 3 4 Sen, Gita; Östlin, Piroska (2007). Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it; Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (PDF) (Report). Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network.

- ↑ Cook, R; Dickens, B; Fathalla, M (2003). Reproductive health and human rights – Integrating medicine, ethics and law. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ George, A (2007). "Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis". Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Ogden, J; Esim, S; Grown, C (2006). "Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus". Health Policy Plan. 21 (5): 333–42. doi:10.1093/heapol/czl025. PMID 16940299.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2006). World Health Report 2006 (PDF) (Report). Geneva.

- ↑ Wamala, S; Lynch, J (2002). Gender and socioeconomic inequalities in health. Lund, Studentlitteratur.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ World Health Organization (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update (PDF) (Report). Geneva.

- ↑ Campbell, J. C. (2002). "Health consequences of intimate partner violence". The Lancet. 359 (9314): 1331–1336. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. PMID 11965295. S2CID 991013.

- ↑ Plichta, S. B.; Falik, M. (2001). "Prevalence of violence and its implications for women's health". Women's Health Issues. 11 (3): 244–258. doi:10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00085-8. PMID 11336864.

- ↑ Farmer, Paul (2005). Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. California: University of California Press.

- ↑ Seager, Roni (2009). The Penguin Atlas of Women in the World, 4th Edition. New York, New York: The Penguin Group.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). World health statistics 2009 (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Karen (12 October 2016). "Bread and Roses: A Gender Perspective on Environmental Justice and Public Health". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (10): 1005. doi:10.3390/ijerph13101005. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 5086744. PMID 27754351.

- 1 2 3 Unger, Nancy C. (18 December 2008). "The Role of Gender in Environmental Justice". Environmental Justice. 1 (3): 115–120. doi:10.1089/env.2008.0523. ISSN 1939-4071.

- 1 2 Engelman, Robert. Macharia, Janet. Kollodge, Richard. (2009). UNFPA state of world population 2009 : facing a changing world : women, population and climate. United Nations Population Fund. ISBN 978-0-89714-958-7. OCLC 472226556.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 "Why Women". WECAN International. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Ivanova, Maria (23 November 2015). "COP21: Why more women need seats at the table". CNN. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ "Women 'more vulnerable to dangers of global warming than men'". The Independent. 1 November 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Health (ASH), Assistant Secretary for (17 November 2015). "Environmental Justice Strategy". HHS.gov. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mager, Natalie A. DiPietro; Liu, Katherine A. (12 March 2016). "Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications". Pharmacy Practice. 14 (1): 708. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. ISSN 1886-3655. PMC 4800017. PMID 27011778.

- ↑ Geller, Stacie E.; Koch, Abby; Pellettieri, Beth; Carnes, Molly (25 February 2011). "Inclusion, Analysis, and Reporting of Sex and Race/Ethnicity in Clinical Trials: Have We Made Progress?". Journal of Women's Health. 20 (3): 315–320. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2469. ISSN 1540-9996. PMC 3058895. PMID 21351877.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (22 January 2020). "Office of Women's Health". FDA. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Parekh, A.; Sanhai, W.; Marts, S.; Uhl, K. (1 June 2007). "Advancing women's health via FDA Critical Path Initiative". Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. 4 (2): 69–73. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2007.10.014. ISSN 1740-6749. PMID 24980844.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (8 February 2019). "Critical Path Initiative". FDA. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (5 May 2020). "Drug Trials Snapshots". FDA.

- 1 2 3 4 Beery, Annaliese K.; Zucker, Irving (1 January 2011). "Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 35 (3): 565–572. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002. ISSN 0149-7634. PMC 3008499. PMID 20620164.

- ↑ Miller, M T (1991). "Thalidomide embryopathy: a model for the study of congenital incomitant horizontal strabismus". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 89: 623–674. ISSN 0065-9533. PMC 1298636. PMID 1808819.

- ↑ Vargesson, Neil (18 October 2018). "The teratogenic effects of thalidomide on limbs". Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 44 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1177/1753193418805249. hdl:2164/11087. ISSN 1753-1934. PMID 30335598. S2CID 53019352.

- 1 2 3 4 Samulowitz, Anke; Gremyr, Ida; Eriksson, Erik; Hensing, Gunnel (2018). ""Brave Men" and "Emotional Women": A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain". Pain Research and Management. 2018: 6358624. doi:10.1155/2018/6358624. PMC 5845507. PMID 29682130.

- ↑ United Nations (1996). Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing 4–15 September 1995 (PDF) (Report). New York: United Nations. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2008). The World Health Report 2008, Primary Health Care: Now more than ever (PDF) (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- 1 2 United Nations (2002). Gender Mainstreaming: An Overview (PDF) (Report). New York: United Nations. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Ravindran, T.K.S.; Kelkar-Khambete, A. (1 April 2008). "Gender mainstreaming in health: looking back, looking forward". Global Public Health. 3 (sup1): 121–142. doi:10.1080/17441690801900761. PMID 19288347. S2CID 5215387.

- 1 2 Ravindran, TKS; Kelkar-Khambete, A (2007). Women's health policies and programmes and gender mainstreaming in health policies, programmes and within the health sector institutions. Background paper prepared for the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2007 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Ostlin, P; Diderichsen, F (2003). "Equity-oriented national strategy for public health in Sweden: A case study" (PDF). European Centre for Health Policy. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Linell, A.; Richardson, M. X.; Wamala, S. (22 January 2013). "The Swedish National Public Health Policy Report 2010". Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 41 (10 Suppl): 3–56. doi:10.1177/1403494812466989. PMID 23341365. S2CID 36416931.

- ↑ Agren, G (2003). Sweden's new public health policy: National public health objectives for Sweden (Report). Stockholm: Swedish National Institute of Public Health.

- ↑ Division for Advancement of Women, United Nations (2005). Enhancing Participation of Women in Development through an Enabling Environment for Achieving Gender Equality and the Advancement of Women, Expert Group Meeting, Bangkok, Thailand, 8 – 11 November 2005 (Report). Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ National Alliance for Caregiving in collaboration with AARP (2009). Caregiving in the U.S. 2009 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Wallerstein, N (2006). What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Health Evidence Network Report (PDF) (Report). Copenhagen: Europe, World Health Organisation. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Manandhar, Dharma S; Osrin, David; Shrestha, Bhim Prasad; Mesko, Natasha; Morrison, Joanna; Tumbahangphe, Kirti Man; Tamang, Suresh; Thapa, Sushma; Shrestha, Dej; Thapa, Bidur; Shrestha, Jyoti Raj; Wade, Angie; Borghi, Josephine; Standing, Hilary; Manandhar, Madan; de L Costello, Anthony M (1 September 2004). "Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 364 (9438): 970–979. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17021-9. PMID 15364188. S2CID 4796493.

- ↑ Pathmanathan, Indra; Liljestrand, Jerker; Martins, Jo. M.; Rajapaksa, Lalini C.; Lissner, Craig; de Silva, Amala; Selvaraju, Swarna; Singh, PrabhaJoginder (2003). "Investing in maternal health : learning from Malaysia and Sri Lanka". The World Bank, Human Development Network. Health, Nutrition, and Population Series.

- ↑ Fikree, Fariyal F; Pasha, Omrana (3 April 2004). "Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 328 (7443): 823–826. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 383384. PMID 15070642.

- ↑ "Data and statistics". www.euro.who.int. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ Rueda, Silvia (September 2012). "Health Inequalities among Older Adults in Spain: The Importance of Gender, the Socioeconomic Development of the Region of Residence, and Social Support". Women's Health Issues. 22 (5): e483–e490. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2012.07.001. ISSN 1049-3867. PMID 22944902.

- ↑ Li, Ailan (2 July 2013). "Implementing the International Health Regulations (2005) in the World Health Organization Western Pacific Region". Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 4 (3): 1–3. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2013.4.3.004. ISSN 2094-7321. PMC 3854098. PMID 24319605.

External links

- Women’s Health: Why do women feel unheard? at the NIHR Evidence website.