Rio de Janeiro is on the far western part of a strip of Brazil's Atlantic coast (between a strait east to Ilha Grande, on the Costa Verde, and the Cabo Frio), close to the Tropic of Capricorn, where the shoreline is oriented east–west. Facing largely south, the city was founded on an inlet of this stretch of the coast, Guanabara Bay (Baía de Guanabara), and its entrance is marked by a point of land called Sugar Loaf (Pão de Açúcar) – a "calling card" of the city.[1]

The center (Centro), the core of Rio, lies on the plains of the western shore of Guanabara Bay. The greater portion of the city, commonly referred to as the North Zone (Zona Norte, Rio de Janeiro), extends to the northwest on plains composed of marine and continental sediments and on hills and several rocky mountains. The South Zone (Zona Sul) of the city, reaching the beaches fringing the open sea, is cut off from the center and from the North Zone by coastal mountains. These mountains and hills are offshoots of the Serra do Mar to the northwest, the ancient gneiss-granite mountain chain that forms the southern slopes of the Brazilian Highlands. The large West Zone (Zona Oeste), long cut off by the mountainous terrain, had been made more easily accessible to those on the South Zone by new roads and tunnels by the end of the 20th century.[2]

The population of the city of Rio de Janeiro, occupying an area of 1,182.3 square kilometers (456.5 sq mi),[3] is about 6,000,000.[4] The population of the greater metropolitan area is estimated at 11–13.5 million. Residents of the city are known as cariocas. The official song of Rio is "Cidade Maravilhosa", by composer André Filho.

Environment

Parks

The city has parks and ecological reserves such as the Tijuca National Park, the world's first urban forest and UNESCO Environmental Heritage and Biosphere Reserve; Pedra Branca State Park, which houses the highest point of Rio de Janeiro, the peak of Pedra Branca; the Quinta da Boa Vista complex; the Botanical Garden;[5] Rio's Zoo; Parque Lage; and the Passeio Público, the first public park in the Americas.[6] In addition the Flamengo Park is the largest landfill in the city, extending from the center to the south zone, and containing museums and monuments, in addition to much vegetation.

General environment and environmental issues

Due to the high concentration of industries in the metropolitan region, the city has faced serious problems of environmental pollution. The Guanabara Bay has lost mangrove areas and suffers from residues from domestic and industrial sewage, oils and heavy metals. Although its waters renew when they reach the sea, the bay is the final receiver of all the tributaries generated along its banks and in the basins of the many rivers and streams that flow into it. The levels of particulate matter in the air are twice as high as that recommended by the World Health Organization, in part because of the large numbers of vehicles in circulation.[7]

The waters of Sepetiba Bay are slowly following the path traced by Guanabara Bay, with sewage generated by a population of the order of 1.29 million inhabitants being released without treatment in streams or rivers. With regard to industrial pollution, highly toxic wastes, with high concentrations of heavy metals – mainly zinc and cadmium – have been dumped over the years by factories in the industrial districts of Santa Cruz, Itaguaí and Nova Iguaçu, constructed under the supervision of State policies.[8]

The Marapendi lagoon and the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon have suffered with the leniency of the authorities and the growth in the number of apartment buildings close by. The illegal discharge of sewage and the consequent deaths of alge diminished the oxygenation of the waters, causing fish mortality.[9][10]

There are, on the other hand, signs of decontamination in the lagoon made through a public-private partnership established in 2008 to ensure that the lagoon waters will eventually be suitable for bathing. The decontamination actions involve the transfer of sludge to large craters present in the lagoon itself, and the creation of a new direct and underground connection with the sea, which will contribute to increase the daily water exchange between the two environments. However, during the Olympics the lagoon hosted the rowing competitions and there were numerous concerns about potential infection resulting from human sewage.[11]

Climate

Rio has a tropical savanna climate (Aw) that closely borders a tropical monsoon climate (Am) according to the Köppen climate classification, and is often characterized by long periods of heavy rain between December and March.[12] The city experiences hot, humid summers, and warm, sunny winters. In inland areas of the city, temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) are common during the summer, though rarely for long periods, while maximum temperatures above 27 °C (81 °F) can occur on a monthly basis.

Along the coast, the breeze, blowing onshore and offshore, moderates the temperature. Because of its geographic situation, the city is often reached by cold fronts advancing from Antarctica, especially during autumn and winter, causing frequent weather changes. In summer there can be strong rains, which have, on some occasions, provoked catastrophic floods and landslides. The mountainous areas register greater rainfall since they constitute a barrier to the humid wind that comes from the Atlantic.[13] The city has had rare frosts in the past. Some areas within Rio de Janeiro state occasionally have falls of snow grains and ice pellets (popularly called granizo) and hail.[14][15][16]

Drought is very rare, albeit bound to happen occasionally given the city's strongly seasonal tropical climate. The Brazilian drought of 2014–2015, most severe in the Southeast Region and the worst in decades, affected the entire metropolitan region's water supply (a diversion from the Paraíba do Sul River to the Guandu River is a major source for the state's most populous mesoregion). There were plans to divert the Paraíba do Sul to the Sistema Cantareira (Cantareira system) during the water crisis of 2014 in order to help the critically drought-stricken Greater São Paulo area. However, availability of sufficient rainfall to supply tap water to both metropolitan areas in the future is merely speculative.[17][18][19]

Roughly in the same suburbs (Nova Iguaçu and surrounding areas, including parts of Campo Grande and Bangu) that correspond to the location of the March 2012, February–March 2013 and January 2015 pseudo-hail (granizo) falls, there was a tornado-like phenomenon in January 2011, for the first time in the region's recorded history, causing structural damage and long-lasting blackouts, but no fatalities.[20][21] The World Meteorological Organization has advised that Brazil, especially its southeastern region, must be prepared for increasingly severe weather occurrences in the near future, since events such as the catastrophic January 2011 Rio de Janeiro floods and mudslides are not an isolated phenomenon. In early May 2013, winds registering above 90 km/h (56 mph) caused blackouts in 15 neighborhoods of the city and three surrounding municipalities, and killed one person.[22] Rio saw similarly high winds (about 100 km/h (62 mph)) in January 2015.[23] The average annual minimum temperature is 21 °C (70 °F),[24] the average annual maximum temperature is 27 °C (81 °F),[25] and the average annual temperature is 24 °C (75 °F).[26] The average yearly precipitation is 1,069 mm (42.1 in).[27]

Temperature also varies according to elevation, distance from the coast, and type of vegetation or land use. During the winter, cold fronts and dawn/morning sea breezes bring mild temperatures; cold fronts, the Intertropical Convergence Zone (in the form of winds from the Amazon Forest), the strongest sea-borne winds (often from an extratropical cyclone) and summer evapotranspiration bring showers or storms. Thus the monsoon-like climate has dry and mild winters and springs, and very wet and warm summers and autumns. As a result, temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F), that may happen about year-round but are much more common during the summer, often mean the actual "feels-like" temperature is over 50 °C (122 °F), when there is little wind and the relative humidity percentage is high.[28][29][30][31]

Rio de Janeiro is second only to Cuiabá as the hottest Brazilian state capital outside Northern and Northeastern Brazil; temperatures below 14 °C (57 °F) occur yearly, while those lower than 11 °C (52 °F) happen less often. The phrase, fazer frio ("making cold", i.e. "the weather is getting cold"), usually refers to temperatures going below 21 °C (70 °F), which is possible year-round and is commonplace in mid-to-late autumn, winter and early spring nights.

Between 1961 and 1990, at the INMET (Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology) conventional station in the neighborhood of Saúde, the lowest temperature recorded was 10.1 °C (50.2 °F) in October 1977,[32] and the highest temperature recorded was 39 °C (102.2 °F) in December 1963.[33] The highest accumulated rainfall in 24 hours was 167.4 mm (6.6 in) in January 1962.[34] However, the absolute minimum temperature ever recorded at the INMET Jacarepaguá station was 3.8 °C (38.8 °F) in July 1974,[32] while the absolute maximum was 43.2 °C (110 °F) on 26 December 2012[35] in the neighborhood of the Santa Cruz station. The highest accumulated rainfall in 24 hours, 186.2 mm (7.3 in), was recorded at the Santa Teresa station in April 1967.[34] The lowest temperature ever registered in the 21st century was 8.1 °C (46.6 °F) in Vila Militar, July 2011.[36]

| Climate data for Rio de Janeiro (station of Saúde, 1961—1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 40.9 (105.6) |

41.8 (107.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

39.3 (102.7) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

42.8 (109.0) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.2 (109.8) |

43.2 (109.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 137.1 (5.40) |

130.4 (5.13) |

135.8 (5.35) |

94.9 (3.74) |

69.8 (2.75) |

42.7 (1.68) |

41.9 (1.65) |

44.5 (1.75) |

53.6 (2.11) |

86.5 (3.41) |

97.8 (3.85) |

134.2 (5.28) |

1,069.4 (42.10) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 11 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 93 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 211.9 | 201.3 | 206.4 | 181.0 | 186.3 | 175.1 | 188.6 | 184.8 | 146.2 | 152.1 | 168.5 | 179.6 | 2,181.8 |

| Source: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).[24][25][26][27][32][33][37][38][39] | |||||||||||||

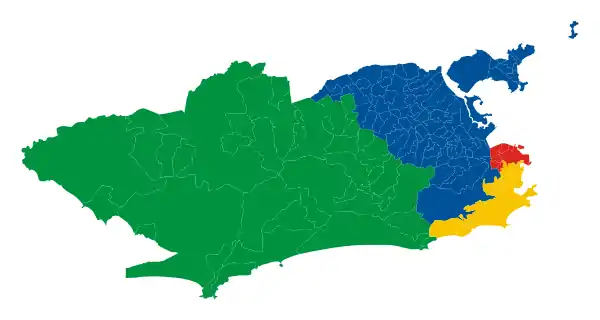

Subdivisions

|

West Zone |

North Zone |

South Zone |

Central Zone |

The city is commonly divided into the historic center (Centro); the tourist-friendly wealthier South Zone (Zona Sul); the residential less wealthy North Zone (Zona Norte); peripheries in the West Zone (Zona Oeste), among them Santa Cruz, Campo Grande and the wealthy newer Barra da Tijuca district. Rio de Janeiro is administratively divided into 33 distritos (districts) named Regiões Administrativas ("Administrative Regions") and 164 bairros (neighborhoods).[40]

Central Zone

Centro or Downtown is the historic core of the city, as well as its financial center. Sites of interest include the Paço Imperial, built during colonial times to serve as a residence for the Portuguese governors of Brazil; many historic churches, such as the Candelária Church (the former cathedral), São Jose, Santa Lucia, Nossa Senhora do Carmo, Santa Rita, São Francisco de Paula, and the monasteries of Santo Antônio and São Bento. The Centro also houses the modern concrete Rio de Janeiro Cathedral. Around the Cinelândia square, there are several landmarks of the Belle Époque of Rio, such as the Municipal Theatre and the National Library building.

Among its several museums, the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts) and the Museu Histórico Nacional (National Historical Museum) are the most important. Other important historical attractions in central Rio include its Passeio Público, an 18th-century public garden. Major streets include Avenida Rio Branco and Avenida Vargas, both constructed, in 1906 and 1942 respectively, by destroying large swaths of the colonial city. A number of colonial streets, such as Rua do Ouvidor and Uruguaiana, have long been pedestrian spaces, and the popular Saara shopping district has been pedestrianized more recently. Also located in the center is the traditional neighborhood called Lapa, an important bohemian area frequented by both townspeople and tourists.

South Zone

The South Zone of Rio de Janeiro (Zona Sul) is composed of several districts, among which are São Conrado, Leblon, Ipanema, Arpoador, Copacabana, and Leme, which compose Rio's famous Atlantic beach coastline. Other districts in the South Zone are Glória, Catete, Flamengo, Botafogo, and Urca, which border Guanabara Bay, and Santa Teresa, Cosme Velho, Laranjeiras, Humaitá, Lagoa, Jardim Botânico, and Gávea. It is the wealthiest part of the city and the best known overseas; the neighborhoods of Leblon and Ipanema, in particular, have the most expensive real estate in all of South America.

The neighborhood of Copacabana beach hosts one of the world's most spectacular New Year's Eve parties ("Reveillon"), as more than two million revelers crowd onto the sands to watch the fireworks display. From 2001, the fireworks have been launched from boats, to improve the safety of the event.[41] To the north of Leme, and at the entrance to Guanabara Bay, is the district of Urca and the Sugarloaf Mountain ('Pão de Açúcar'), whose name describes the famous mountain rising out of the sea. The summit can be reached via a two-stage cable car trip from Praia Vermelha, with the intermediate stop on Morro da Urca. It offers views of the city second only to Corcovado mountain. Hang gliding is a popular activity on the Pedra Bonita (literally, "Beautiful Rock"). After a short flight, gliders land on the Praia do Pepino (Pepino, or "cucumber", Beach) in São Conrado.

Since 1961, the Tijuca National Park (Parque Nacional da Tijuca), the largest city-surrounded urban forest and the second largest urban forest in the world, has been a National Park. The largest urban forest in the world is the Floresta da Pedra Branca (White Rock Forest), which is located in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro.[42]

The Pontifical Catholic University of Rio (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro or PUC-Rio), Brazil's top private university, is located at the edge of the forest, in the Gávea district. The 1984 film Blame It on Rio was filmed nearby, with the rental house used by the story's characters sitting at the edge of the forest on a mountain overlooking the famous beaches. In 2012, CNN elected Ipanema the best city beach in the world.[43]

North Zone

The North Zone (Zona Norte) begins at Grande Tijuca (the middle class residential and commercial bairro of Tijuca), just west of the city center, and sprawls for miles inland until Baixada Fluminense and the city's Northwest.[44] This region is home to the Maracanã stadium (located in Grande Tijuca), once the world's highest capacity football venue, able to hold nearly 199,854 people,[45] as it did for the World Cup final of 1950.

More recently its capacity has been reduced to conform with modern safety regulations and the stadium has introduced seating for all fans. Currently undergoing reconstruction, it now has the capacity for 78,838.[46] Maracanã was the site for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies and football competition of the 2007 Pan American Games; hosted the final match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, the Opening and Closing Ceremonies and the football matches of the 2016 Summer Olympics.[47]

Besides Maracanã, the North Zone of Rio also has other tourist and historical attractions, such "Nossa Senhora da Penha de França Church", the Christ the Redeemer (statue) with its stairway built into the rock bed, 'Manguinhos', the home of Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, a centenarian biomedical research institution with a main building fashioned like a Moorish palace, and the Quinta da Boa Vista, the park where the historic Imperial Palace is located. Nowadays, the palace hosts the National Museum, specializing in natural history, archeology, and ethnology.

The International Airport of Rio de Janeiro (Galeão – Antônio Carlos Jobim International Airport, named after the famous Brazilian musician Antônio Carlos Jobim), the main campus of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro at the Fundão Island, and the State University of Rio de Janeiro, in Maracanã, are also located in the Northern part of Rio. This region is also home to most of the samba schools of Rio de Janeiro such as Mangueira, Salgueiro, Império Serrano, Unidos da Tijuca, Imperatriz Leopoldinense, among others. Some of the main neighborhoods of Rio's North Zone are Alto da Boa Vista which shares the Tijuca Rainforest with the South and Southwest Zones; Tijuca, Vila Isabel, Méier, São Cristovão, Madureira, Penha, Manguinhos, Fundão, Olaria among others. Many of Rio de Janeiro's slums (favelas), are located in the North Zone.[48]

West Zone

West Zone (Zona Oeste) of Rio de Janeiro is a vaguely defined area that covers some 50% of the city's entire area, including Barra da Tijuca and Recreio dos Bandeirantes neighborhoods. The West Side of Rio has many historic sites because of the old "Royal Road of Santa Cruz" that crossed the territory in the regions of Realengo, Bangu, and Campo Grande, finishing at the Royal Palace of Santa Cruz in the Santa Cruz region. The highest peak of the city of Rio de Janeiro is the Pedra Branca Peak (Pico da Pedra Branca) inside the Pedra Branca State Park. It has an altitude of 1024m. The Pedra Branca State Park (Parque Estadual da Pedra Branca)[49] is the biggest urban state park in the world comprising 17 neighborhoods in the west side, being a "giant lung" in the city with trails,[50] waterfalls and historic constructions like an old aqueduct in the Colônia Juliano Moreira[51] in the neighborhood of Taquara and a dam in Camorim. The park has three principal entrances: the main one is in Taquara called Pau da Fome Core, another entrance is the Piraquara Core in Realengo and the last one is the Camorim Core, considered the cultural heritage of the city.

The Barra da Tijuca is an elite area of the West Zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro. It includes Barra da Tijuca, Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Vargem Grande, Vargem Pequena, Grumari, Itanhangá, Camorim and Joá. Westwards from the older zones of Rio, Barra da Tijuca is a flat complex of barrier islands of formerly undeveloped coastal land, which constantly experiences new constructions and developments. It remains an area of accelerated growth, attracting some of the richer sectors of the population as well as luxury companies. High rise flats and sprawling shopping centers give the area a far more modern feel than the crowded city center. The urban planning of the area, completed in the late 1960s, mixes zones of single-family houses with residential skyscrapers. The beaches of Barra da Tijuca are also popular with the residents from other parts of the city. One of the most famous hills in the city is the 842-meter-high (2,762-foot) Pedra da Gávea (Crow's nest Rock) bordering the South Zone. On the top of its summit is a huge rock formation resembling a sphinx-like, bearded head that is visible for many kilometers around.

Santa Cruz and Campo Grande Region have exhibited economic growth, mainly in the Campo Grande neighborhood. Industrial enterprises are being built in lower and lower middle class residential Santa Cruz, one of the largest and most populous of Rio de Janeiro's neighborhoods, most notably Ternium Brasil, a new steel mill with its own private docks on Sepetiba Bay, which is planned to be South America's largest steel works.[52] A tunnel called Túnel da Grota Funda, opened in 2012, creating a public transit facility between Barra da Tijuca and Santa Cruz, lessening travel time to the region from other areas of Rio de Janeiro.[53]

References

- ↑ "Where is Rio de Janeiro?". Riobrazilblog.com. 8 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Rio de Janeiro – History.com Articles, Video, Pictures and Facts Archived 22 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Area Territorial Official" (in Portuguese). IBGE. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑ "Estimativas para 1° de Julho de 2006" (in Portuguese). IBGE. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑ ""Cochicho da Mata" recria floresta dentro da floresta" (in Portuguese). Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. 7 October 2005. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "Parque Estadual da Pedra Branca (PEPB)". Governo do Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Instituto Nacional do Ambiente. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Afra Balazina (21 September 2007). "Estudo revela poluição elevada em seis capitais" [Study reveals high pollution levels in six capitals]. Folha Online (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ↑ "Contexto ambiental da Baía de Sepetiba" (in Portuguese). Observatório Quilombola (OQ). 2001. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ↑ Hélio Almeida (11 January 2011). "Lagoa de Marapendi sofre com poluição da água" [Marapendi Lagoon suffers with water pollution] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ Agência Brasil (18 May 2010). "Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas estará despoluída até 2014, diz secretário" [Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon will be unpolluted until 2014, says secretary]. O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "For rowers in Rio's Olympic water, it's all about avoiding the splash". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ Alvares, Clayton Alcarde; Stape, José Luiz; Sentelhas, Paulo Cesar; de Moraes Gonçalves, José Leonardo; Sparovek, Gerd (2013). "Köppen's climate classification map for Brazil". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 22 (6): 711–728. Bibcode:2013MetZe..22..711A. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507.

- ↑ "BBC Weather – Rio de Janeiro". BBC Weather. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Hail falls in Rio de Janeiro's West Zone and Baixada Fluminense" (in Portuguese). Globo News. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ "Chuvinha de granizo – Nova Iguaçu 18-2-2013" [Little hail shower – Nova Iguaçu, 18 February 2013] (in Portuguese). YouTube. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ "As hail falls, Rio enters a warning interval" (in Portuguese). G1. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Brazil drought crisis leads to rationing and tensions". The Guardian. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Brazil's worst drought in history prompts protests and blackouts". The Guardian. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Paraíba do Sul River might not have enough water to rescue São Paulo's Sistema Cantareira" (in Portuguese). G1. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Tornado is responsible for havoc in Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro" (in Portuguese). Globo. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Tornado is responsible for havoc in Nova Iguaçu" (in Portuguese). Gazeta do Povo. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ Storm with winds above 90 km/h (56 mph) kill one in Rio (in Portuguese)

- ↑ "Bangu windstorm, inside the city of Rio, achieved near-cyclone speed" (in Portuguese). G1. 3 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Mínima (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Máxima (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Média Compensada (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Precipitação Acumulada Mensal e Anual (mm)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ "Com sensação térmica de 48°C, cariocas se refugiram do calor nas praias" [Feeling like 48°C, cariocas bathe in beaches trying to escape from the heat] (in Portuguese). G1. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "Sensação térmica no Rio de Janeiro chega a 50°C nesta terça-feira" [Rio de Janeiro will be feeling like 50°C this Tuesday] (in Portuguese). Yahoo! Notícias. 25 December 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "Sensação térmica no Rio ultrapassa os 50 graus" [Rio de Janeiro's feels like is now greater than 50 celsius] (in Portuguese). Rede TV!. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "Sensação térmica no Rio chega aos 51 graus, diz pesquisa do Inpe" [Feels like in Rio gets in 51 celsius mark, according to research]. O Globo (in Portuguese). 3 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Temperatura Mínima Absoluta (°C)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet). Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Máxima Absoluta (°C)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet). Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Máximo Absoluto de Precipitação Acumulada (mm)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ "Temperatura desta quarta no Rio é recorde histórico, diz Inmet" (in Portuguese). G1 Rio de Janeiro. 26 December 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ "Record lowest temperature since 7.3 °C (45.1 °F) in 2000". Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ "Número de Dias com Precipitação Maior ou Igual a 1 mm (dias)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ "Insolação Total (horas)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ "Umidade Relativa do Ar Média Compensada (%)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ "Regiões de Planejamento (RP), Regiões Administrativas (RA) e Bairros do Município do Rio de Janeiro". Data.Rio. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ Rio Reveillon Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Engelbrecht Ferreira, Daniel Ernesto (April 2005). "Poluição afeta Pedra Branca". O Globo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑ Forgan, Duncan (23 May 2012). "World's best city beaches #2". CNNGo.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Facts about North Zone - Rio

- ↑ 1950 World Cup Final registered the largest audience at Maracanã: 199,854 people

- ↑ Maracanã Stadium

- ↑ North Zone of Rio de Janeiro

- ↑ "Reinventing Rio" Archived 17 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Alan Riding, September 2010, Smithsonian

- ↑ "Inea – Portal". www.inea.rj.gov.br. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ "[PDF] Trail Guide of Pedra Branca State".

- ↑ "Bispo do Rosário Museum, the contemporary museum of Colônia".

- ↑ "SIDERÚRGICA DO ATLÂNTICO VAI GERAR 18 MIL EMPREGOS NA ZONA OESTE". Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Topo do blog Quais serão os novos ares cariocas?". Veja Rio (in Portuguese). 19 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014.