.jpg.webp)

The geology of the Canary Islands is dominated by volcanic rock. The Canary Islands and some seamounts to the north-east form the Canary Volcanic Province whose volcanic history started about 70 million years ago.[1] The Canary Islands region is still volcanically active. The most recent volcanic eruption on land occurred in 2021[2] and the most recent underwater eruption was in 2011-12.[1]

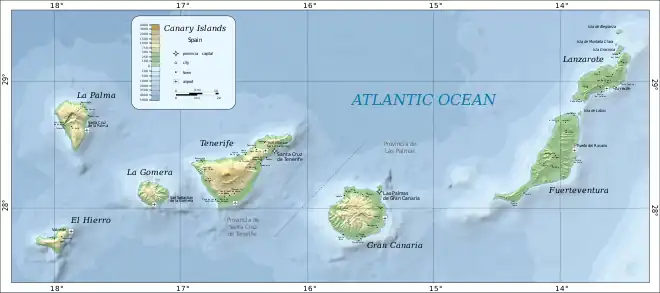

The Canary Islands are a 450 km (280 mi) long, east-west trending, archipelago of volcanic islands in the North Atlantic Ocean, 100–500 km (62–311 mi) off the coast of Northwest Africa.[3] The islands are located on the African tectonic plate. The Canary Islands are an example of intraplate volcanism because they are located far (more than 600 km (370 mi)) from the edges of the African Plate.[4]

From east to west, the main islands are Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Gomera, La Palma, and El Hierro.[Note 1] There are also several minor islands and islets. The seven main Canary Islands originated as separate submarine seamount volcanoes on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, which is 1,000–4,000 m (3,300–13,100 ft) deep in the Canarian region.

Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are parts of a single volcanic ridge called the Canary Ridge. These two present-day islands were a single island in the past. Part of the ridge has been submerged and now Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are separate islands, separated by an 11 km (6.8 mi) wide, 40 m (130 ft) deep strait of ocean water.[6]

Volcanic activity has occurred during the last 11,700 years on all of the main islands except La Gomera.[7]

Regional setting

Volcanic activity in the Canary Volcanic Province started about 70 Ma (million years ago), occurring at numerous seamounts and the Savage Islands, across an area of the ocean floor up to 400 km north of the Canary Islands. The northernmost of this group of seamounts, Lars seamount (about 380 km north of Lanzarote), has been dated to 68 Ma. The seamounts are progressively younger southwestwards towards Lanzarote.[8]

The Canary Islands are built upon one the oldest regions of Earth's oceanic crust (147 to 175 Ma), part of the slow-moving African Plate in the continental rise section of northwest Africa's passive continental margin.[9][10] The oceanic lithosphere is about 60 km thick at the central Canary Islands and about 100 km thick at the western islands.[11]

Two seamounts, Las Hijas (southwest of El Hierro) and El Hijo de Tenerife (about 200,000 years old, located between Gran Canaria and Tenerife) may eventually (in the next 500,000 years) form new islands by future eruptions adding more lava flows to their volcanic edifices.[12]

Growth stages

Volcanic oceanic islands, such as the Canary Islands, form in deep parts of the oceans. This type of island forms by a sequence of development stages:[13]

- (1) submarine (seamount) stage

- (2) shield-building stage

- (3) declining stage (La Palma and El Hierro)

- (4) erosion stage (La Gomera)

- (5) rejuvenation/post-erosional stage (Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Gran Canaria and Tenerife).[13]

The Canary Islands differ from some other volcanic oceanic islands, such as the Hawaiian Islands, in several ways – for example, the Canary Islands have stratovolcanoes, compression structures and a lack of subsidence.[13]

The seven main Canary Islands originated as separate submarine seamount volcanoes on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Each seamount, built up by the eruption of many lava flows, eventually became an island. Subaerial volcanic eruptions continued on each island. Fissure eruptions dominated on Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, resulting in relatively subdued topography with heights below 1,000 m (3,300 ft). The other islands are much more rugged and mountainous. In the case of Tenerife, the volcanic edifice of Teide rises about 7,500 m (24,600 ft) above the ocean floor (about 3,780 m (12,400 ft) underwater and 3,715 m (12,188 ft) above sea level).[14][15]

The volume of volcanic rock that has build up the Canary Islands to thousands of metres above the ocean floor is about 124,600 km3; 96% of this lava is hidden below sea level and only 4% (4,940 km3) is above sea level.[16] The western islands have more of their volume (7%) above sea level than do the eastern islands (2%).[16]

Age

The age of the oldest subaerially-erupted lavas on each island decreases from east to west along the island chain: Lanzarote-Fuerteventura (20.2 Ma), Gran Canaria (14.6 Ma), Tenerife (11.9 Ma), La Gomera (9.4 Ma), La Palma (1.7 Ma) and El Hierro (1.1 Ma).[17][4]

Rock types

Volcanic rock types found on the Canary Islands are typical of oceanic islands. The volcanic rocks include alkali basalts, basanites, phonolites, trachytes, nephelinites, trachyandesites, tephrites and rhyolites.[13][7]

Outcrops of plutonic rocks (for example, syenites, gabbros and pyroxenites) occur on Fuerteventura,[18] La Gomera and La Palma. Apart from some islands of Cape Verde (another island group in the Atlantic Ocean, about 1,400 km (870 mi) south-west of the Canary Islands), Fuerteventura is the only oceanic island known to have outcrops of carbonatite.[19]

Volcanic landforms

Examples of the following types of volcanic landforms occur in the Canary Islands: shield volcano, stratovolcano, collapse caldera, erosion caldera, cinder cone, coulee, scoria cone, tuff cone, tuff ring, maar, lava flow, lava flow field, dyke, volcanic plug.[20]

Origins of volcanism

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the volcanism of the Canary Islands.[21] Two hypotheses have received the most attention from geologists:

- The volcanism is related to crustal fractures extending from the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

- The volcanism is caused by the African Plate moving slowly over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle.

Currently, a hotspot is the explanation accepted by most geologists who study the Canary Islands.[22][23]

Evidence in favour of a hotspot origin for Canarian volcanism includes the age progression in the arcuate Canary Volcanic Province occurring in the same direction and at the same rate as in the neighbouring arcuate Madeira Volcanic Province (about 450 km farther north). This is consistent with the African Plate rotating at about 12 mm per year.[24]

Seismic tomography has revealed the existence of a region of hot rock extending from the surface, down through the oceanic lithosphere to a depth of at least 1,000 km in the upper mantle.[25]

Volcanic eruption distribution

Seventy-five confirmed volcanic eruptions have occurred in the Canary Islands in the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years of Earth's geological history).[26] Sixteen of these eruptions have been during the Modern Era of European history (that is, after c.1480).[26] Therefore, in the last 500 years, volcanic eruptions have occurred, on average, every 30 to 35 years.[27] However, in the Modern Era, the repose period between infrequent eruptions at each volcano has been highly variable (26 to 237 years for Cumbre Vieja on La Palma; 1 to 212 years for Tenerife), making reliable prediction of future eruptions unlikely.[28][26]

| Island | Holocene (last 11,700 years) | Modern Era (since c. 1480) | Modern Era eruption dates | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanzarote | 4 | 2 | 1730–1736, 1824 | [29] | |

| Fuerteventura | 0 | 0 | —— | No specific confirmed Holocene eruptions but they are inferred to have occurred (based on the freshness of lava and volcanic landforms) | [30] |

| Gran Canaria | 11 | 0 | —— | [31] | |

| Tenerife | 42 | 5 | 1492, 1704–1705, 1706, 1798, 1909 | [32] | |

| La Gomera | 0 | 0 | —— | [27] | |

| La Palma | 14 | 8 | 1481(±11), 1585, 1646, 1677–1678, 1712, 1949, 1971, 2021 | [33] | |

| El Hierro | 4 | 1 | 2011–2012 | [34] |

Lanzarote

Volcanic activity at Lanzarote started during the Oligocene Epoch at 28 Ma.[35] For about the first 12 million years, the lava pile of a submarine seamount built up from the 2,500 m deep sea floor.[36] Then, in the Miocene Epoch, from 15.6 Ma to 12 Ma, the Los Ajaches subaerial shield volcano grew as an island on top of the seamount, in an area corresponding to present-day southern Lanzarote.[37] Between 10.2 Ma and 3.8 Ma, volcanic activity was focussed about 35 km to the northeast, forming a second shield volcanic island called Famara.[38] Between Los Ajaches and Famara volcanoes, a central volcanic edifice was also active from 6.6 to 6.1 Ma.[39] The edifices gradually merged to form a single island, Lanzarote, at about 4 Ma.[40] From 3.9 Ma to 2.7 Ma, volcanic activity paused and the island was eroded.[41] Today, although the lavas of Los Ajaches volcano are now mostly covered by calcrete,[42] the eroded remains of the two shield volcanoes are preserved in southern and northern Lanzarote respectively, with small outcrops of the central edifice occurring between them. At about 2.7 Ma, in the late Pliocene Epoch, the rejuvenation stage began. It produced much less lava than the earlier shield stage, mainly at the Montaña Roja and Montaña Bermeja volcanoes in southern Lanzarote.[41] Then, throughout the subsequent Pleistocene and Holocene epochs, the rejuvenation volcanism has continued and has been dominated by strombolian-style eruptions of lava from sets of volcanic cones aligned along numerous NE-SW fissures in the central part of Lanzarote.[43] Geologically recent examples of rejuvenation stage volcanism include eruptions at Montaña Corona (about 21,000 years ago), Timanfaya (1730-1736) and Tao/Nuevo del Fuego/Tinguatón (1824).[44][45][46]

The Timanfaya eruption (1730–1736) erupted more than one billion cubic metres (1 km3) of lava, and a large volume of pyroclastic tephra, from more than 30 volcanic vents along a 14 km-long fissure in western Lanzarote. The lava flows covered one quarter of the island (an area of about 225 km2) with some of the flows reaching about 50 m in thickness. It is the largest Modern Era eruption in the Canary Islands, and the third largest eruption of basaltic lava on Earth in historical times.[47][48][49][50][51]

Almost all the volcanic rocks of Lanzarote are basaltic.[52]

Earthquakes

The seismicity of the Canary Islands is low. Earthquakes that occur on or near the Canary Islands are linked to volcanism and tectonism. Most earthquakes in the region have had an intensity of VI or less on the Modified Mercalli Scale. The Timanfaya eruptions on Lanzarote in 1730, however, were accompanied by earthquakes with intensities of up to X on the same scale.[53]

From 1975 to November 2023, 168 earthquakes of magnitude 2.5 or larger, with epicentres on or close to the Canary Islands, have been recorded; the largest of these earthquakes had a moment magnitude of 5.4 and an intensity of VII and occurred on the ocean floor about 28 km west of El Hierro in 2013.[54]

In 2004, an earthquake swarm occurred on Tenerife, which raised concern that a volcanic eruption may have been about to occur but no such eruption followed the swarm.[55][56]

Earthquake swarms, due to the underground movement of molten magma, were detected before and during the volcanic eruptions of 2011-2012 and 2021.

In the week before the 2021 eruption on La Palma, a swarm of more than 22,000 earthquakes occurred, with mbLg magnitudes up to about 3.5. The epicentres of successive earthquakes migrated upwards as magma rose slowly to the surface.[57][58][59] During the eruption, larger earthquakes were detected, for example an earthquake of mbLg magnitude 4.3 occurred 35 km below the surface.[60]

See also

Further reading

- Carracedo, Juan Carlos; Day, Simon (1 January 2002). The Canary Islands (Classic Geology in Europe). Terra Books. ISBN 978-1903544075.

Notes

- ↑ Since 2018, La Graciosa has been officially designated "la octava isla canaria habitada"[5] (the eighth inhabited island of the Canary Islands), in effect the eighth "main island". This is only a political and social designation. La Graciosa continues to be a geologically minor island of the Canary Islands, associated with its much larger neighbour Lanzarote.

References

- 1 2 Carracedo, J.C.; Troll, V.R.; Zaczek, K.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Soler, V.; Deegan, F.M. (2015) The 2011–2012 submarine eruption off El Hierro, Canary Islands: New lessons in oceanic island growth and volcanic crisis management, Earth-Science Reviews, volume 150, pages 168–200, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.06.007

- ↑ "Lava shoots up from volcano on La Palma in Spanish Canary Islands". Reuters. 2021-09-19. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ↑ Schmincke, H.U. and Sumita, M. (1998) Volcanic Evolution of Gran Canaria reconstructed from Apron Sediments: Synthesis of VICAP Project Drilling in Weaver, P.P.E., Schmincke, H.U., Firth, J.V., and Duffield, W. (editors) (1998) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, volume 157

- 1 2 Carracedo, Juan Carlos; Troll, Valentin R. (2021-01-01), "North-East Atlantic Islands: The Macaronesian Archipelagos", in Alderton, David; Elias, Scott A. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Geology (Second Edition), Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 674–699, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102908-4.00027-8, ISBN 978-0-08-102909-1, S2CID 226588940, retrieved 2021-03-16

- ↑ "El Senado reconoce a La Graciosa como la octava isla canaria habitada". El País (in Spanish). 26 June 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) The Geology of the Canary Islands, Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, page 532

- 1 2 Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) “Volcanoes of Europe”, Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 101

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) "The Geology of the Canary Islands", Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, page 9

- ↑ Lang, N.P., Lang, K.T., Camodeca, B.M. (2012) "A geology-focused virtual field trip to Tenerife, Spain", Geological Society of America Special Paper 492, pages 323-334, doi: 10.1130/2012.2492(23)

- ↑ Vera, J.A. (editor) (2004) "Geologia de Espana", Madrid, SGE-IGME (in Spanish) page 637

- ↑ Schmincke, H.U. and Sumita, M. (1998) "Volcanic Evolution of Gran Canaria reconstructed from Apron Sediments: Synthesis of VICAP Project Drilling" in Weaver, P.P.E., Schmincke, H.-U., Firth, J.V., and Duffield, W. (editors) (1998) "Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results", volume 157.

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) "The Geology of the Canary Islands", Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, pages 9-11

- 1 2 3 4 Viñuela, J.M. (2007). "The Canary Islands Hot Spot" (PDF). www.mantleplumes.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J.C. Canary Islands, Geology in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) Encyclopedia of Islands, page 134

- ↑ Martínez-García, E. Spain in Moores, E.M. and Fairbridge, R. (editors) (1997) Encyclopedia of European and Asian Regional Geology, London, Chapman and Hall, ISBN 0-412740-400, page 680

- 1 2 Paris, R. (2002) "Rythmes de noconstruction et de destruction des édifices volcaniques de point chaud : I'exemple des lIes Canaries (Espagne)", Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne - Universidad de Las Palmas - Laboratoire de Géographie Physique CNRS, Doctoral Thesis, page 15, table 1 (in French)

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C and Troll, V.R. (editors) (2013) “Teide Volcano:Geology and Eruptions of a Highly Differentiated Oceanic Stratovolcano”, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-642-25892-3, Page 24

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J.C. Canary Islands, Geology in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) Encyclopedia of Islands, page 140

- ↑ Bell, K.; Tilton, G.R. (2002). "Probing The Mantle: The Story From Carbonatites". Eos. 83 (25): 273–280. doi:10.1029/2002EO000190. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20.

- ↑ Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) Volcanoes of Europe. Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 100

- ↑ Vonlanthen, P.; Kunze, K.; Burlini, L.; Grobety, B. (2006). "Seismic properties of the upper mantle beneath Lanzarote (Canary Islands): Model predictions based on texture measurements by EBSD". Tectonophysics. 428: 65–85. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.09.005.

- ↑ Yepes, J.A. (2007). "The Canary Islands Topobathymetric Relief Map - Aspect Of The Sea Bed And Geology" (PDF). Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO). Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Weis, F.A.; Skogby, H.; Troll, V.R.; Deegan, F.M.; Dahren, B. (2015). "Magmatic water contents determined through clinopyroxene: Examples from the Western Canary Islands, Spain". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 16 (7): 2127–2146. doi:10.1002/2015GC005800. hdl:10553/72171. S2CID 128390629.

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J-C. "Canary Islands, Geology" in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) "Encyclopedia of Islands", page 142

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) "The Geology of the Canary Islands", Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, pages 15-16

- 1 2 3 Spain Volcanoes – Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 26 November 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcanolist_countries.cfm?country=Spain

- 1 2 Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) "Volcanoes of Europe", Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 101

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J.C. "Canary Islands, Geology" in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) "Encyclopedia of Islands", page 135

- ↑ Lanzarote - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383060

- ↑ Fuerteventura - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383050

- ↑ Gran Canaria - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383040

- ↑ Tenerife - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383030

- ↑ La Palma - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383010

- ↑ Hierro - Eruption history ; Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, retrieved 08 Nov 2023; https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=383020

- ↑ Hansen Machin, A. and Perez Torrado, F. (2005) "The Island and it's Territory: Volcanism in Lanzarote", Sixth International Conference on Geomorphology, Field Trip Guide C-1, page 6

- ↑ Becerril, L. et al. (2017) "Assessing qualitative long-term volcanic hazards at Lanzarote Island (Canary Islands)", Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., volume 17, pages 1145–1157, doi=10.5194/nhess-17-1145-2017

- ↑ Coello et al. (1992) "Evolution of the eastern volcanic ridge of the Canary Islands based on new K-Ar data", Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, volume 53, pages 251-274

- ↑ Hansen Machin, A. and Perez Torrado, F. (2005) "The Island and it's Territory: Volcanism in Lanzarote", Sixth International Conference on Geomorphology, Field Trip Guide C-1, page 7

- ↑ Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME) Cartográfica de Canarias (GRAFCAN) (2015) "Descripción de las Unidades Geológicas de Lanzarote" for "Mapa Geológico de Canarias", Instituto Geológico y Minero de España; Madrid, Spain: 2015. Gobierno de Canarias, CARTOGRAF, FEDER, Programa MAC 2007–2013, 1992–1994, page 2

- ↑ Hansen Machin, A. and Perez Torrado, F. (2005) "The Island and it's Territory: Volcanism in Lanzarote", Sixth International Conference on Geomorphology, Field Trip Guide C-1, page 8

- 1 2 Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME) Cartográfica de Canarias (GRAFCAN) (2015) "Descripción de las Unidades Geológicas de Lanzarote" for "Mapa Geológico de Canarias", Instituto Geológico y Minero de España; Madrid, Spain: 2015. Gobierno de Canarias, CARTOGRAF, FEDER, Programa MAC 2007–2013, 1992–1994, page 3

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Day, S. (2002) “Canary Islands”, Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-07-6, page 58

- ↑ Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME) Cartográfica de Canarias (GRAFCAN) (2015) "Descripción de las Unidades Geológicas de Lanzarote" for "Mapa Geológico de Canarias", Instituto Geológico y Minero de España; Madrid, Spain: 2015. Gobierno de Canarias, CARTOGRAF, FEDER, Programa MAC 2007–2013, 1992–1994, pages 3 and 4

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Day, S. (2002) “Canary Islands”, Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-07-6, pages 1–11, 57

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J-C. “Canary Islands, Geology” in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) “Encyclopedia of Islands”, page 140

- ↑ Lanzarote and Chinijo Archipelago Geopark http://www.geoparquelanzarote.org/geologia/

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) "The Geology of the Canary Islands", Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, page 486

- ↑ Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J-C. "Canary Islands, Geology" in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) "Encyclopedia of Islands", page 140

- ↑ Carracedo J.C. and Perez Torrado, F.J. "Cenozoic Volcanism in the Canary Islands: Canarian geochronology, stratigraphy and evolution: an overview" in Gibbons, W. and Moreno, T. (editors) (2002) "Geology of Spain", London, The Geological Society, ISBN 1-86239-110-6, page 463

- ↑ Schmincke, H.U. and Sumita, M. (1998) "Volcanic Evolution of Gran Canaria reconstructed from Apron Sediments: Synthesis of VICAP Project Drilling" in Weaver, P.P.E., Schmincke, H.-U., Firth, J.V., and Duffield, W. (editors) (1998) "Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results", volume 157

- ↑ Padilla, G. et al. (2010) "Diffuse CO2 Emission from Timanfaya Volcano, Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain", Cities on Volcanoes - Conference 6 - Abstracts

- ↑ Mitchell-Thomé, Raoul C. (1976) "Geology of the Middle Atlantic Islands", Berlin, Gebrueder Borntraeger, ISBN 3-443-11012-6, pages 170 and 174

- ↑ González de Vallejoa, L.I.; Tsigé, M.; Cabrera, L. (2005). "Paleoliquefaction features on Tenerife (Canary Islands) in Holocene sand deposits". Engineering Geology. 76 (3–4): 179–190. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2004.07.006.

- ↑ Earthquakes of the Canary Islands 1975–2023 – USGS Earthquake Catalog retrieved on 26 November 2023.

- ↑ Domínguez Cerdeña, I.; del Fresno, C.; Rivera, L. (2011) "New insight on the increasing seismicity during Tenerife's 2004 volcanic reactivation", Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, volume 206, issues 1-2, pages 15-29, doi=10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.005

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C.; Troll, V.R.; Zaczek, K.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Soler, V.; Deegan, F.M. (2015) "The 2011–2012 submarine eruption off El Hierro, Canary Islands: New lessons in oceanic island growth and volcanic crisis management", Earth-Science Reviews, volume 150, pages 168–200, DOI=10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.06.007

- ↑ Suarez, Borja (2021-09-19). "Lava shoots up from volcano on La Palma in Spain's Canary Islands". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ "La Palma Update: The intensity of earthquakes has increased". Canarian Weekly. 19 September 2021. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ↑ "Noticias e informe mensual de vigilancia volcánica" (in Spanish). Instituto Geográfico Nacional. 2 October 2021.

- ↑ "La Palma registra un terremoto de 4,3: el más intenso desde el inicio de la actividad volcánica". rtve.es (in Spanish). 7 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.