| George II გიორგი II | |

|---|---|

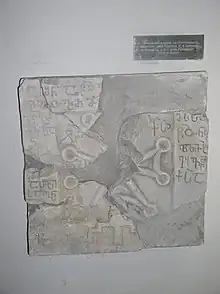

Façade stone of the Khuap church with the Georgian asomtavruli inscription probably commemorating George II | |

| King of Abkhazia | |

| Reign | 923–957 |

| Predecessor | Constantine III |

| Successor | Leon III |

| Spouse | Helen |

| Dynasty | Anchabadze (Anosid) dynasty |

| Religion | Chalcedonian |

George II (Georgian: გიორგი II, Giorgi II), of the Leonid dynasty was a king of Abkhazia from 923 to 957 AD.[upper-alpha 1] His lengthy reign is regarded as a zenith of cultural flowering and political power of his realm. Despite being independent and locally titled as a Mepe (king), he is also regarded as Exousiastes,[upper-alpha 2] the title that was addressed to him by Byzantines.

George II continued the expansionist policy of his predecessor, aiming primarily at unification of Georgia. It took him, however, some time to assume full ruling powers as his half-brother Bagrat also claimed the crown.

Life

In 923, King Constantine III of Abkhazia (r. 894–923) died, and George, then George II Abkhazia succeeded him. However, Bagrat, George's youngest brother, also claimed the crown, the latter engineered a coup with the support of a party of nobles, most importantly his father-in-law, Gurgen II of Tao (r. 918–941). The conflict lasted for nearly seven years and ended with the sudden death of Bagrat in 930. To secure the allegiance of the local nobility in central Georgia, George appointed his son Constantine as a duke/viceroy of Kartli in 923, but the latter too, revolted against him in 926. In response, George entered in Kartli and placed the rock-hewn city of Uplistsikhe under siege. He lured Constantine by treachery and had him blinded and castrated. In the same year, he installed another son, Leon (the future king Leon III), as a duke/viceroy of Kartli.

George II aided by the rebellious Kakhetian (Gardabanian clan) nobles proceeded to campaign against the Kvirike II, Prince-bishop of Kakheti. He succeeded in dispossessing Kvirike of his principality in the 930s.[2] To secure his supremacy over Kartli, George allied himself with the Georgian Bagratids of Tao-Klarjeti, and gave his daughter, Gurandukht to Gurgen Bagrationi in marriage. Soon Kvirike returned to offensive and incited rebellion in Kartli. George sent a large army under his son, Leon, but the king died amid the expedition, and Leon had to make peace with Kvirike, ending his campaign inconclusively.

Cultural life

George was also known as a promoter of Orthodox Christianity and a patron of Georgian Christian culture. He helped to establish Christianity as an official religion in Alania, winning the thanks of Constantinople.[3] In the first half of the 10th century he founded Khopa (Gudauta district) and Kiachi (Ochamchire district) cathedrals, as well as Ckhondidi cathedral (Martvili district) to counter the Greek cathedrals, and, by virtue of this, new cathedrals were a mainstay of the central state-power against external and internal enemies.

Character

The Georgian Chronicles describes him:

“He had all the virtues, courage and boldness; was faithful to God, was famous as the builder of the churches, merciful towards the poor, generous, modest, full of noble features and kind”.[4]

Quote from Byzantine patriarch Nicholas Mystikos's letter addressed to King George, written immediately after his accession on the throne.

“...You (George), an intelligent, sensible man...”[5]

18th century Georgian historian Vakhushti Bagrationi describes him:

“George was the God-Fearing and pious king, stately, bold and courageous, merciful, generous, church builder, kind to orphans and widows”.[4]

Family

George married a certain Helen:

Issue

- Constantine, Duke/Viceroy of Kartli (923–926);

- Leon III, Duke/Viceroy of Kartli (926–957); King of Abkhazia (960–969).

- Demetrius III, King of Abkhazia (969–976).

- Theodosius III, sent to Constantinople to be educated there; King of the Abkhazia (975–978).

- Bagrat, sent to Constantinople to be educated there;

- Anonymous daughter, married to Prince Shurta of Kakheti (Kvirike II's brother);

- Gurandukht, married to Prince Gurgen Bagrationi;

- Anonymous daughter, married to Abas I of Armenia.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of George II of Abkhazia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Genealogy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Cyril Toumanoff 915/916 to 959/960, while according to René Grousset, who cites Marie-Félicité Brosset, from 921 to 955.

- ↑ The term was in currency in the 10th and 11th centuries owing to the fact that, at that time, the term basileus ("king") was reserved for the Byzantine monarch only.[1]

Sources

- Marie-Félicité Brosset, Histoire de la Géorgie, et Additions IX, p. 175.

- Анчабадзе З. В., Из истории средневековой Абхазии (VI-XVII вв.), Сух., 1959;

References

- ↑ Toumanoff, Cyril (1963). Studies in Christian Caucasian history. Washington: Georgetown University Press. p. 107 n. 165.

- ↑ Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1780230306.

- ↑ Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1780230306.

- 1 2 Gamaxaria, Jemal. Beradze, T. (Tamaz) Gvancʻelaże, Tʻeimuraz, 1951- (2011). Abkhazia : from ancient times till the present days; assays [essays] from the history of Georgia. Ministry of Education and Culture of Abkhazia. ISBN 9789941039287. OCLC 1062190076.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Vinogradov, Andrey (2017). "History of Christianity in Alania Before 932" (PDF). SSRN Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2949816. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 165071247.