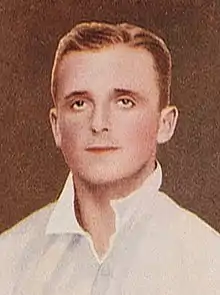

Macaulay at the third Test vs. Australia at Headingley Stadium in 1926 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | George Gibson Macaulay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 7 December 1897 Thirsk, Yorkshire, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 13 December 1940 (aged 43) Sullom Voe, Shetland Islands, Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 10.5[1] in (1.79 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm medium-fast Right-arm off spin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Bowler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 211) | 1 January 1923 v South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 22 July 1933 v West Indies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1920–1935 | Yorkshire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Cricinfo, 15 March 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

George Gibson Macaulay (7 December 1897 – 13 December 1940) was a professional English cricketer who played first-class cricket for Yorkshire County Cricket Club between 1920 and 1935. He played in eight Test matches for England from 1923 to 1933, achieving the rare feat of taking a wicket with his first ball in Test cricket. One of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1924, he took 1,838 first-class wickets at an average of 17.64 including four hat-tricks.

A leading member of the Yorkshire team which achieved a high level of success in the time he played, Macaulay was a volatile character who played aggressively. He left a job at a bank to become a professional cricketer, making his first-class debut aged 23 as a fast bowler. Meeting limited success, he altered style to deliver off spin in addition to his pace bowling. This proved so effective that he was chosen to play for England in Test matches. However, his perceived poor attitude towards the game, and an unsuccessful match in the 1926 Ashes probably prevented him playing more Tests. His form slumped following injuries in the late 1920s, but a recovery in the early 1930s led to a recall by England, although he broke down in his second match back. Another injury in 1934 made cricket difficult for him and his first-class career ended in 1935, although he continued playing club cricket until the Second World War. A pilot officer in the Royal Air Force, he died of pneumonia on active service in the Second World War.

Early life

Macaulay was born in Thirsk on 7 December 1897. His father was a well-known local cricketer, as were his uncles.[2] Macaulay was educated at Barnard Castle; in later years, he took teams of famous cricketers to play annual matches against the school eleven.[3] Upon leaving school, he worked as a bank clerk in Wakefield;[4] there, and in nearby Ossett, he played cricket and football.[5] In the First World War, Macaulay served with the Royal Field Artillery;[6] afterwards he returned to work for the same bank as before, initially in London,[4] then in Herne Bay, Kent, playing club cricket in his spare time.[2][5]

Playing career

Yorkshire debut

In 1920, Yorkshire needed to strengthen its bowling attack. Of the team's previously successful bowlers, Major Booth had been killed in the war, Alonzo Drake had died soon afterwards from illness, and George Hirst was past his best. Although Wilfred Rhodes was able to ease the shortfall by resuming his career as a frontline spin bowler, Yorkshire needed new bowlers, particularly pacemen.[2][7] Macaulay had been spotted playing club cricket by Sir Stanley Christopherson, a former Kent player.[5] Subsequently, Harry Hayley, a 19th-century Yorkshire cricketer, saw Macaulay in action and was sufficiently impressed to recommend him for a trial with the county.[2] At the beginning of the 1920 season, Macaulay played in two warm-up games for Yorkshire, taking six wickets for 52 runs in a one-day game and four for 24 and two for 19 in a two-day game.[notes 1][8] This was good enough to earn a first-class debut on 15 May 1920 against Derbyshire in the County Championship, although he only took one wicket.[8] Playing in the early part of the season, he took five wickets for 50 runs, his first five-wicket haul, against Gloucestershire, followed by six for 47 against Worcestershire.[2][8] He continued to play until the middle of June before dropping out of the team after an unsuccessful match against Surrey.[8][9] In ten first-class matches, he had taken 24 wickets at an average of 24.35,[10] and managed a top score of just 15 with the bat.[11] Wisden said he "had neither the pace nor the stamina required",[5] while it later said he tried to bowl at speeds beyond his capability. Even so, he decided to become a professional cricketer. Hirst and Rhodes persuaded him to reduce his pace and concentrate on bowling a good length while trying to spin the ball. He practised through the winter of 1920–21 to be ready for the next season.[2][3]

Bowling a mixture of medium pace and his new style of off spin,[12] Macaulay played 27 matches in 1921. After taking wickets steadily at the start of the season, in his fourth game he took six wickets for ten runs as Warwickshire were bowled out for 72. Four more wickets in the second innings gave Yorkshire a big victory and Macaulay had match figures of ten wickets for 65 runs, the first time he had taken ten wickets in a match.[8] Macaulay then came to wider public attention by taking six wickets for three runs to bowl out Derbyshire for 23 runs.[3][8] He later took ten wickets in the match against Surrey in a losing cause,[8] and in total that season he took 101 first-class wickets at an average of 17.33,[10] placing him third in the Yorkshire bowling averages.[13] With the bat, he scored 457 runs at an average of 22.59, surprising commentators with his ability.[11] This included a maiden first-class century against Nottinghamshire. His innings of 125 not out took Yorkshire from 211 for seven wickets when he came in to bat (228 for eight soon after) to a total of 438 for nine declared, a lead of 264; Yorkshire went on to a comfortable win.[2][14] His overall success in the season meant that his place in the team was secure.[2]

Macaulay improved his bowling record in 1922, taking more wickets at a lower average (133 wickets at an average of 14.67),[10] and scoring another century.[11] Helping Yorkshire to win the first of four County Championships in a row,[15] Macaulay finished second to Rhodes in the team's bowling averages.[notes 2][16] The first two matches of the season brought Macaulay figures of six for eight and five for 23 in a ten wicket win over Northamptonshire and six for 12 out of an opposition total of 78 in an innings win over Glamorgan. While he took only one wicket in the second innings, his first three innings had given him 17 wickets for 43 runs.[8] He continued to pick up wickets, but his most significant performance came in June. In front of Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) members at Lord's, he took five for 31 as Middlesex were bowled out for 138. Those watching were impressed and he was selected for the Players against the Gentlemen at the same ground in July. He took three for 97 out of a total of 430 in one of the most important matches of the season.[notes 3][2][8][18] These performances earned his selection for the MCC tour to South Africa that winter,[notes 4] although there were concerns his fitness was insufficient.[2] Statistically, Macaulay's best performance came shortly afterwards against Gloucestershire; he took seven for 47 and twelve wickets in the match.[8] Macaulay also scored 486 runs at an average of 17.35.[11]

Test debut

Macaulay played eight first-class matches in South Africa in 1922–23, taking 29 wickets at an average of 16.37.[10] His best first-class performances were six for 18 against Pretoria and eight wickets in the match against Transvaal, while he was effective in minor matches, taking five for 40 against East Rand and six for 19 against Zululand.[8] After England lost the first Test match, which Wisden attributed to a weakness in bowling, Macaulay replaced Greville Stevens and made his Test match debut for England in the second Test.[20][21][22] He took the wicket of George Hearne with his first ball. He was the fourth player to take a wicket with his maiden delivery in Test cricket.[23] In total, he took two for 19 in the first innings. In the second innings, South Africa were comfortably placed with a score of 157 for one, but four wickets fell to Macaulay while 13 runs were scored. Macaulay ended the innings with five wickets for 64.[22] Wisden commented that he bowled very finely in this match. He hit the winning run, batting at number eleven, to seal a one-wicket win for England.[22][24] He played in the remaining three Tests, finishing with 16 wickets at an average of 20.37.[25] England won the series 2–1, but the Wisden correspondent for the tour was not impressed by the English performances, noting that no really effective bowlers had emerged.[26]

With his health improved by the tour, Wisden reported that Macaulay was in excellent form for the whole of the 1923 season.[2] His performances earned him selection as one of Wisden's Cricketers of the Year. The citation praised his stamina, spin and ability to bowl on all kinds of pitches but noted that he was easily discouraged and had a negative attitude if circumstances went against him.[2] He achieved his highest season total of wickets to date, taking 166 at an average of 13.84, and came third in both the Yorkshire and national bowling averages.[11][27][28] His best performance came in the first match of the season, when he took seven wickets for 13 against Glamorgan as they were dismissed for 63.[8] Later in the season, he took a hat-trick against Warwickshire while claiming five for 42.[29] With the bat, Macaulay scored 463 runs at an average of 18.52.[11] There were no international matches that season, but Macaulay was selected for The Rest in a Test trial against England in which he took just one wicket.[notes 5][8]

In 1924, Macaulay further increased his total of wickets to 190 and lowered his bowling average to 13.23, placing him first in the national averages.[10][30][31] His batting declined as he scored 395 runs at an average of 11.96.[11] Although selected for another Test trial, Macaulay did not play in the series against the touring South African team until the third Test at Leeds, where he took one wicket in each South African innings, but was omitted from the final two Tests.[8] Despite his success in the season, he was not chosen to tour Australia with the MCC that winter, even though Maurice Tate, the leading bowler on the tour, lacked support.[12] Macaulay had been involved in controversy on the field in 1924. At the time, the Yorkshire team were notorious for their aggressive attitude while fielding.[32] In a match against Middlesex in 1924 at Sheffield, the hostility of the crowd provoked an MCC inquiry which found that Yorkshire bowler Abe Waddington had incited the spectators.[33] Further incidents followed against Surrey.[34] The editor of Wisden blamed Yorkshire's poor discipline on a small group of approximately four players. Without naming Macaulay as one of them, he noted that Lord Hawke, the Yorkshire president, believed Macaulay should have been in the team to Australia, and that "it was entirely his own fault he was not chosen".[35] It is also possible that during a match at this time, Macaulay openly criticised the captaincy and bowling of Arthur Gilligan, the England captain.[36]

Since 1923, Macaulay had run a cricket outfitters in Leeds and Wakefield with his Yorkshire team-mate Herbert Sutcliffe, borrowing £250 from his mother to help establish the business. During the winter of 1924–25, the shop became a limited company and Macaulay one of its directors.[4][37] According to Sutcliffe's biographer Alan Hill, Macaulay quickly lost interest, and the partnership was dissolved a year later, but Sutcliffe made the lone venture a success.[37] Macaulay received £900 from the outfitters upon his resignation.[4]

Mid-1920s career

Macaulay's most successful season in terms of wickets was 1925, despite a very dry summer which produced a succession of good batting pitches. He took 211 wickets at an average of 15.48, coming top of the Yorkshire averages.[10][38][39] Exactly 200 of his wickets were taken for Yorkshire—only Wilfred Rhodes and George Hirst had previously reached 200 wickets for Yorkshire, and only Bob Appleyard has done so since, as of 2013.[40] One of Macaulay's highest profile performances in 1925 came for Yorkshire against Sussex, who were chasing 263 to win the game. Just after lunch on the final day, the score was 223 for three wickets. A possibly apocryphal story suggests that Macaulay drank champagne in the interval.[40] He then delivered a spell of five wickets for eight runs in 33 balls to bowl out his opponents and finish with figures of seven for 67.[41][42] He then left the field exhausted. The cricket historian Mick Pope describes the match as a "lasting testimony to [Macaulay's] belief that no cause was ever lost".[43] Macaulay was again selected for the Players against the Gentlemen at Lord's, and took five wickets in the match.[8] With the bat, Macaulay scored 621 runs at an average of 23.88, although he only passed fifty twice.[11]

Yorkshire's reign as County Champions ended in 1926, the first season since 1921 when Yorkshire did not win the Championship.[15] Wisden noted that the Yorkshire attack, with the exception of Rhodes, was less effective than previously.[38] Macaulay bowled fewer overs and took fewer wickets at a higher bowling average; his 134 wickets, at an average of 17.78, placed him second in the Yorkshire averages.[10][44] Selected for a Test trial, he failed to take a wicket. Wisden described his performance as "lifeless",[45] while cricket writer Neville Cardus noted that he had "yet again ... fallen below his best away from the Yorkshire XI".[46] He was not chosen for the Gentlemen v Players match, never representing the Players again.[8]

Macaulay was selected for the third Test against Australia at Headingley, possibly because Arthur Carr, the England captain, expected the pitch to favour spinners. The Australians were concerned that Macaulay represented a threat to their batting, but the match did not work out in Macaulay's favour as a bowler; having been dropped at the start of play, Charlie Macartney played what Wisden called one of the best innings of his career and vigorously attacked the England bowling, achieving the rare feat of scoring a century before the lunch interval. The Australian batsman had asked his captain if he could attack Macaulay in particular, and the Yorkshire bowler suffered as Macartney quickly dominated him. Macaulay eventually had Macartney caught after hitting a short ball in the air, but it was Macaulay's only success in the innings. Macaulay conceded 123 runs in 32 overs as Australia scored 494.[47][48][49] When Macaulay came into bat from number ten in the batting order, England were 182 for eight wickets and facing defeat. He played an attacking innings of 76, hitting ten fours, in a partnership of 108 with George Geary. This began an England recovery which helped the team to escape with a draw.[47][50] Nevertheless, Macaulay did not play in the final two Tests of the series.[8] Later in the season, he took fourteen wickets for 92 runs against Gloucestershire, including eight for 43 in the second innings. These were the best bowling figures of his career that he achieved in a match.[8] Apart from his batting success in the Test match, Macaulay scored another two fifties and in the match against Somerset achieved a century.[8][11]

Decline

Over the next four seasons, Yorkshire failed to win the Championship, although they never finished lower than fourth in the table.[51] The team displayed an unaccustomed weakness in bowling, particularly after the death of Roy Kilner in 1928. The effectiveness of the main bowlers was reduced by age and injury; only Macaulay remained at something approaching his bowling peak.[52] However, his performances worsened each year. His bowling figures in the 1927 season were similar to his achievements in 1926, showing only a slight decline, but his total of wickets fell each season until 1930.[10]

In 1927, Macaulay took 130 wickets at an average of 18.26.[10] However, he suffered a foot injury in 1928, and took time to recover his best form.[53] His wicket tally fell to 120 and his average climbed to 24.37.[10] His total of wickets decreased further to 102 in 1929 and his average remained above 20. Hampered by another foot injury throughout 1930, Macaulay failed to take 100 wickets for the first time since his debut season; his average of 25.12 was the highest of his career.[notes 6][10][58] In these seasons, he was only selected for one representative match, a Test trial in 1928 in which he failed to take a wicket.[8] At the same time, his batting faded. In 1927, Macaulay scored his highest run aggregate and passed fifty six times while hitting 678 runs at an average of 25.11. He improved his batting average in 1928, accumulating 517 runs at 25.85 with four more fifties. However, after 1928, he never averaged more than 16.26 with the bat and only scored two more fifties in his career, both in 1929.[11]

End of first-class career

Return to form

From the 1931 season, Yorkshire once again dominated the County Championship, winning three consecutive trophies.[15] A large part of the success was an increase in bowling strength.[59] In 1931, Macaulay slightly increased his haul of wickets from 91 to 97, and his average dropped from 25.12 to 15.75.[10] This placed him third in the Yorkshire averages, behind Hedley Verity and Bill Bowes, who both took over 100 wickets and led a very strong bowling attack.[59][60] That season, Macaulay was awarded a benefit match against Surrey which raised £1,633,[3][61] worth approximately £82,700 in 2008.[62] At the time, this was considered a poor reward for a Yorkshire cricketer.[3] The following season, Macaulay took fewer wickets, managing 84 at an average of 19.07,[10] which placed him fifth in the Yorkshire averages.[63] He achieved his best bowling figures in first-class cricket when he took eight for 21 against the Indian touring side.[8] By now, Macaulay was a specialist spinner and had largely abandoned pace bowling; Bill Bowes and Arthur Rhodes opened the Yorkshire bowling.[64]

The 1933 season signalled a return to form for Macaulay. Wisden judged that he "recovered fully his length, spin and command over variations in pace".[40] He bowled more overs than anyone else in the team and passed 100 wickets for the first time since 1929, the tenth and final time he did so, taking 148 wickets at an average of 16.45.[10][65] Against Northamptonshire, he took seven for nine as the team was bowled out for 27. He finished the match with thirteen for 34.[8] Against Lancashire, when his match figures were twelve for 49, he took a hat-trick in a sequence of four wickets in five balls;[66] he also took twelve wickets against Leicestershire.[8] His form won a recall to the Test side after seven years. Not picked initially, a decision described by Wisden as unfair, he played in the first Test when E. W. Clark dropped out of the team before the match.[67] Macaulay took one wicket in the first innings but had figures of four for 57 in the second innings to earn approval from Wisden.[8][67] He was picked for the second Test but bowled only 14 overs before injuring his foot when fielding; he was unable to take any further part in the game.[8][68] He did not play in the third Test but was selected in festival game at Scarborough for the team selected from the MCC party which toured Australia in the previous winter. He played instead of an injured player, even though he did not take part in the tour.[69] Macaulay ended second in the Yorkshire bowling averages.[70] In its review of the season, Wisden stated that his form in the early part of the season would have placed his among the best cricketers in the world.[40]

Final seasons

Macaulay's final two seasons were affected by injury, as he was increasingly bothered by rheumatism.[71] In the 1934 season, while trying to take a catch, he injured the finger he used to spin the ball.[3] He did not appear for Yorkshire until June,[72] but went on to take 55 wickets at an average of 23.43.[10] The next season was his final one. He only played nine matches,[11] taking 22 wickets at 20.09.[10] At the end of the year, he retired from first-class cricket and Yorkshire awarded him a special grant of £250.[3] Yorkshire did have a replacement in mind; Frank Smailes was considered to be versatile enough in his bowling style to take Macaulay's place,[65] but it was not until Ellis Robinson secured a place in 1937 that a new specialist off-spinner was found.[73]

Macaulay ended his career with 1,837 first-class wickets at an average of 17.65. In eight Test matches, he took 24 of those wickets at an average of 27.58. In addition, he scored 6,055 runs at an average of 18.07 and held 373 catches.[74] He took 100 wickets in a season ten times, a record only surpassed by four others for Yorkshire, while only three other Yorkshire bowlers have taken 200 wickets in a season.[75] He also took four hat-tricks.[76]

Post-Yorkshire career

Following his retirement, Macaulay initially attempted to market a patented rheumatic medicine, but the business quickly failed. He then established an athletic outfitting shop in Leeds. This business also was unsuccessful;[4] Macaulay blamed a lack of money and competition from other businesses. Consequently, he filed for bankruptcy in 1937.[77] Macaulay accused Yorkshire of worsening his situation by withholding most of his benefit money—of the total raised, he received only £530. He believed that he was owed the balance, and continued his business under that assumption, but Yorkshire had invested the amount and he only received the interest. The matter arose in court, and when asked why he thought the money would be paid to him, Macaulay answered: "Because I had earned it".[78] He also rejected the accusation that he spent his time drinking in public houses,[78] and another that he had neglected his two failed businesses.[4] The Official Receiver found that Macaulay's complaint against Yorkshire was without justification. Macaulay suggested that he should arrange for the invested money to be paid to his creditors in his will. Macaulay secured new employment,[77] and a few days after the hearing it was announced that he would play professional cricket in Wales.[79]

Macaulay played league cricket in Wales and Lancashire until the Second World War.[3] During 1937, he was the professional at Ebbw Vale cricket club,[79] and in 1938 and 1939, he played in the Lancashire League as the professional for Todmorden, for whom he took nine wickets for 10 runs against Ramsbottom in the Worsley Cup final. Ramsbottom were bowled out for 47 to give Macaulay's team a 26-run win.[3][80][81]

When the Second World War began, Macaulay joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) Volunteer Reserve in 1940 as a Pilot Officer, and was stationed at Church Fenton, close to Barkston Ash where he lived with his wife Edith. Later in the year, he was stationed in the Shetland Islands, where he was bothered by the cold.[82] Six days after his 43rd birthday,[82] he died of pneumonia at the Sullom Voe RAF station on 13 December 1940. He was buried in Lerwick Cemetery in Shetland.[83][84]

Style and personality

As a batsman, Macaulay was reasonably good and possibly better than his statistics would suggest. He was capable of batting well in a crisis but may have been prevented from honing his batting skills by the Yorkshire leadership who wished him to focus on bowling.[5] He generally batted low down in the order after the all-rounders in the team.[85] Macaulay's fielding was also very effective. He was excellent at close range to the batsmen,[3] particularly from his own bowling.[5]

As a bowler, Macaulay fulfilled two roles. At the start of an innings, when the ball was new and hard, he opened the bowling with medium-fast deliveries that swung away from right-handed batsmen. In this style, he was very accurate and bowled a variety of deliveries to unsettle his opponents. Cricket writer R. C. Robertson-Glasgow considered him to be better than any similar bowler in the 1920s except Maurice Tate, the leading medium paced bowler in England.[12] Macaulay could vary his pace from medium to fast depending on the needs of the match situation and the type of pitch.[86] When the pitch was suitable for spinning the ball, he bowled medium-paced off breaks.[12] Wisden said that his spin made him more effective than other bowlers of his speed on a sticky wicket, a pitch which has been affected by rain, making it erratic and difficult to bat on.[2] His obituary further stated: "Under suitable conditions for using the off-break, batsmen seemed at his mercy."[3] This was because he could bowl deliveries which were almost impossible for batsmen to play without getting out, but at the same time it was very difficult to score runs against him.[3] Robertson-Glasgow wrote that "on a rain-damaged pitch he was in his glory."[12] He would make small adjustments to the positions of his fielders or bowl from different sides of the wicket, often making gestures or facial expressions as he did so. Robertson-Glasgow said that "only the best could survive the onslaught except by a miracle",[12] and described Macaulay as a great bowler.[86] The cricket writer Jim Kilburn suggested that Macaulay was "a great cricketer. He was great not so much in mathematical accomplishment ... as in cricketing character."[87]

Macaulay's bowling action was relaxed and effortless, being admired by his contemporaries.[3][86] Kilburn wrote: "His run-up was half-shambling, his steps short and his shoulders swaying, but his feet were faultlessly placed and his aim was high at the instant of delivery".[87] However, critics and team-mates more widely knew him as passionate, hostile and fiery when bowling.[6] Kilburn said that batsmen were Macaulay's "mortal enemies".[87] He knew many tricks to dismiss or unsettle them, including the tactic of bowling the ball straight at their head without pitching, which was usually considered dangerous and unfair.[88] Kilburn observed that "should the batsman survive he would be rewarded with a glare of concentrated venom calculated to stagger any but the stoutest heart ... Every scrap of his heart and soul went into every ball he bowled. He never gave up and his persistence was invariably triumphant sooner or later".[87] The Yorkshire Post, after his death, observed: "Macaulay will always be remembered for the fierceness of his enthusiasm when there was a fighting chance of victory".[89]

Macaulay displayed a temper when matters went against him.[5] Robertson-Glasgow described him as an unusual man, "fiercely independent, witty, argumentative, swift to joy and anger. He had pleasure in cracking a convention or cursing an enemy ... A cricket-bag came between him and his blazer hanging on a peg; and he'd kick it and tell it a truth or two, then laugh."[86] Bill Bowes described how, when he was bowling, he would glare and mutter under his breath; he seemed to be "filled with a devilish energy".[90] He would make sharp or biting comments, particularly if a fielder made a mistake when he was bowling and although often amusing, it could at times hurt the recipients, and his anger made his team-mates wary of him.[6][91] Yet, he could also express appreciation when a skillful batsmen hit a good shot from his bowling; the result was that his colleagues were never sure what to expect from him, even after playing with him for years.[92] Herbert Sutcliffe said he could be charming when not playing, but his wit could be sharp.[6] Robertson-Glasgow nevertheless described him as "a glorious opponent; a great cricketer; and a companion in a thousand".[12]

Notes

- ↑ Bowling figures are given in the form of six for 52; the first figure refers to how many wickets the bowler took in the innings and the second figure shows how many runs he gave away. In this case, Macaulay took six wickets and conceded 52 runs.

- ↑ The placings for Yorkshire bowling averages include only bowlers who took ten wickets or more in that season.

- ↑ As a concentration of the best talent in the country, the Gentlemen v Players matches each season served as a thorough examination of a player's ability—some players believed these games more demanding than a Test trial match.[17]

- ↑ The MCC was responsible for the administration of English cricket, including the England Test team. The England team toured under the MCC name and playing colours.[19]

- ↑ The Rest was a team which represented the rest of England, the best players not included in the Test team.

- ↑ During this period from 1927 to 1930, Macaulay's bowling figures kept him near the head of the Yorkshire bowling averages. He was top in 1927 and in the leading four for the next two seasons.[54][55][56] However, in 1930 he dropped to sixth.[57]

References

- ↑ "Answers to Correspondents". Sheffield Daily Telegraph/British Newspaper Archive. Sheffield. 27 June 1923. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Wisden – George Macaulay". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1924. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Wisden – Obituaries during the war, 1940". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1941. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Former County Cricketer: Leeds Bankruptcy Court Examination". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencier. Leeds. 13 January 1937. p. 3. Retrieved 30 September 2014. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Woodhouse, p. 306.

- 1 2 3 4 Hodgson, p. 109.

- ↑ Rogerson, Sidney (1960). Wilfred Rhodes. London: Hollis and Carter. pp. 120–21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "Player Oracle GG Macaulay". CricketArchive. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ Woodhouse, p. 305.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "First-class Bowling in Each Season by George Macaulay". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "First-class Batting and Fielding in Each Season by George Macaulay". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robertson-Glasgow, p. 136.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1921". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ "Nottinghamshire v Yorkshire in 1921". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 "County Champions 1890–present". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1922". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players in 1922". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ "MCC History". Marylebone Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ "South Africa v England 1922–23". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1924. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ "South Africa v England in 1922/23 (first Test)". CricketArchive. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 "South Africa v England in 1922/23 (second Test)". CricketArchive. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ "Wicket with first ball in career". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ "South Africa v England 1922–23". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1924. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ "Test Bowling in Each Season by George Macaulay". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ "MCC team in South Africa 1922–23". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1924. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1923". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ Woodhouse, p. 327.

- ↑ "Warwickshire v Yorkshire in 1923". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1924". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ↑ Woodhouse, p. 333.

- ↑ Hill, p. 106.

- ↑ Hill, pp. 106–07.

- ↑ Hill, p. 107.

- ↑ Pardon, Sydney (1925). "Notes by the Editor". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, p. 106. Marshall claims that the incident took place in the 1924 Lord's Test, but Macaulay did not play in that game.

- 1 2 Hill, pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 Rogerson, p. 142.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1925". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Pope, p. 166.

- ↑ "Remarkable Bowling by Macaulay". The Times. London. 19 August 1925. p. 6. Retrieved 12 June 2010. (subscription required)

- ↑ "Yorkshire v Sussex in 1925". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Pope, pp. 165–66.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1926". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ↑ Caine, Stewart (1927). "Notes by the Editor". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Cardus, Neville (1979). Play Resumed with Cardus. London: MacDonald Queen Anne Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-356-19049-8.

- 1 2 "England v Australia 1926". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1927. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Cardus, Neville (1959). "Charles Macartney and George Gunn". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Perry, Roland (2002). Bradman's best Ashes teams: Sir Donald Bradman's selection of the best ashes teams in cricket history. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. pp. 110–12. ISBN 1-74051-125-5.

- ↑ "England v Australia in 1926". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Woodhouse, pp. 344, 350, 358, 366–67.

- ↑ Woodhouse, pp. 358, 367.

- ↑ Hodgson, p. 122.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1927". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1928". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1929". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1930". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Hodgson, p. 128.

- 1 2 Woodhouse, p. 368.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1931". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Bowes, p. 72.

- ↑ Calculated using the Retail Price Index in £ at, Lawrence H. Officer. "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present". Measuringworth.com. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1932". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Hodgson, p. 132.

- 1 2 Hodgson, p. 136.

- ↑ "Lancashire v Yorkshire in 1933". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- 1 2 "England v West Indies 1933". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1934. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "England v West Indies 1933". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1934. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Scarborough Festival". The Times. London. 7 September 1933. p. 5. Retrieved 6 August 2010. (subscription required)

- ↑ "First-class Bowling for Yorkshire in 1933". CricketArchive. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Hodgson, p. 138.

- ↑ "First-Class Matches played by George Macaulay". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ Hodgson, p. 145.

- ↑ "George Macaulay". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Most wickets in a Season for Yorkshire". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "Hat-Tricks for Yorkshire". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- 1 2 "County Cricketers Benefit: Complaints Answered". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 10 February 1937. p. 13. ProQuest 484158587. (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Cricketer and his Benefit: Amount which was invested". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 13 January 1937. p. 4. ProQuest 484124388. (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Ebbw professional". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 9 February 1937. p. 4. ProQuest 484161956. (subscription required)

- ↑ Woodhouse, pp. 306–07.

- ↑ "Todmorden v Ramsbottom in 1938". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- 1 2 Pope, pp. 166–67.

- ↑ Woodhouse, p. 307.

- ↑ Swanton, p. 61.

- ↑ Marshall, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 Robertson-Glasgow, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 4 Kilburn, J. M. (17 December 1940). "George Macaulay". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. p. 2.

- ↑ Bowes, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Quoted in Pope, p. 167.

- ↑ Bowes, p. 64.

- ↑ Bowes, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Bowes, p. 81.

Bibliography

![]() Media related to George Macaulay at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Macaulay at Wikimedia Commons

- Bowes, Bill (1949). Express Deliveries. London: Stanley Paul. OCLC 643924774.

- Hill, Alan (2007). Herbert Sutcliffe: Cricket Maestro. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Stadia. ISBN 978-0-7524-4350-8.

- Hodgson, Derek (1989). The Official History of Yorkshire County Cricket Club. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-85223-274-9.

- Marshall, Michael (1987). Gentlemen and Players: Conversations with Cricketers. London: Grafton Books. ISBN 0-246-11874-1.

- Pope, Mick (2013). Headingley Ghosts: A Collection of Yorkshire Cricket Tragedies. Leeds: Scratching Shed Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9568043-9-6.

- Robertson-Glasgow, R. C. (1943). Cricket Prints: Some Batsmen and Bowlers 1920–1940. London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd. OCLC 651926233.

- Swanton, E. W. (1999). Cricketers of My Time. London: Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-99746-6.

- Woodhouse, Anthony (1989). The History of Yorkshire County Cricket Club. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7470-3408-7.