George Walbridge Perkins I | |

|---|---|

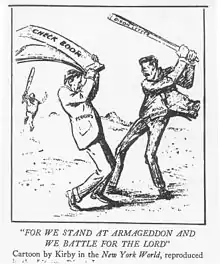

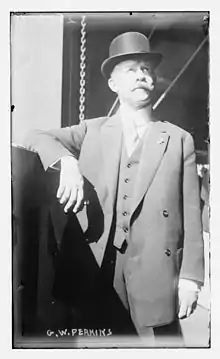

Perkins in 1914 | |

| Born | January 31, 1862 |

| Died | June 18, 1920 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx, New York |

| Children | George Walbridge Perkins Jr. |

| Signature | |

George Walbridge Perkins I (January 31, 1862 – June 18, 1920) was an American politician and businessman. He was a leader of the Progressive Movement, especially Theodore Roosevelt's presidential candidacy for the Progressive Party in 1912.

Starting as an office boy, he became a leading executive in insurance, steel, and banking and was always on the alert for new and better ways to do business. He was a top aide to financier J. P. Morgan and handled complex issues involving U.S. Steel, International Harvester, and other large corporations and insurance companies. He was vice-president of New York Life Insurance Company and a partner in J.P. Morgan & Co. He served as president of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission from its creation in 1900 to his death.

Biography

Perkins was born on January 31, 1862, in Chicago.[1]

With only a high-school education, he began work as an office boy in the Chicago office of the New York Life Insurance Company. By 1898 he had risen to the position of vice president. Perkins played an important role in the development of New York Life.

A strong believer in the Efficiency Movement, he sought out instances of waste and believed that any practice could be improved by careful analysis. For example, he noticed that the old routine of farming out territory to middlemen, who in turn appointed men who did the actual soliciting for policies, was inefficient. The local agents were underpaid and often made misrepresentations in order to get initial premiums. Perkins, starting in 1892, made the local agents and solicitors permanent employees. In 1896, he introduced an incentive with a system of benefits based on length of service and value of policies written. He opened up new insurance markets in Russia and elsewhere in Europe.

Morgan & Co.

Perkins joined J.P. Morgan & Co. in 1901 and negotiated many complex deals, especially the formation of the International Harvester Corporation, International Mercantile Marine Co., and Northern Securities Company. He also helped reorganize Morgan's United States Steel Corporation.[2]

Political career

In 1910 Perkins began to pursue Progressive Era reform causes. Perkins was an articulate exponent of the evils of competition and the advantages of cooperation in business— he believed in the Good Trust. His biographer, John A. Garraty, summarized Perkins' business philosophy as follows:

The fundamental principle of life is co-operation rather than competition... Competition is cruel, wasteful, destructive, outmoded; co-operation, inherent in any theory of a well-ordered Universe, is humane, efficient, inevitable and modern.[3]

In 1912 he helped organize Theodore Roosevelt's new Progressive party, becoming its executive secretary. At the convention, an antitrust plank was suddenly dropped, shocking reformers like Gifford Pinchot, who saw Roosevelt as a true trust-buster. They blamed Perkins, who was still on the board of U.S. Steel and remained on it until his death. Perkins's ties to big business alarmed the radical wing of the party. Roosevelt lost to the Democrat Woodrow Wilson

After 1913, he focused on New York City politics while he continued as Progressive National Chairman. In 1916 he campaigned for Charles Evans Hughes and the GOP. The result was a deep split in the new party that was never resolved. Perkins was in effective control of the party in 1913, but the Progressives fared poorly in local elections. He went public with his denunciations of antitrust programs, arguing, "The country knows that the Progressive Party believes that large business units are necessary in this day of interstate and inter-national communication and trade."[4]

Increasingly at odds with Progressives hostile to big business and humbled by the party's very poor showing in the 1914 elections, Perkins watched his Progressive Party support the Republican presidential candidate (Charles Evans Hughes) in 1916, after which the party and soon disintegrated.

On September 7, 1917, the New York State Senate rejected his nomination as Chairman of the recently-established New York State Food Control Commission.[5] On October 2, the State Senate rejected again his nomination and instead confirmed the appointment of John Mitchell, Jacob Gould Schurman and Charles A. Wieting to the Food Control Commission.[6]

As chairman of a finance committee of YMCA, he raised $200,000,000 for welfare work among American soldiers abroad.

Palisades Interstate Park Commission

In 1900, Theodore Roosevelt (then New York governor) appointed Perkins president of the newly formed Palisades Interstate Park Commission. It had been formed with the aim of stopping the destruction of the Palisades, a line of steep cliffs along the west side of the lower Hudson River, in northeast New Jersey and southern New York. Although the Palisades and the Hudson Highlands were admired for their beauty, and were featured in paintings of the Hudson River School, they were also viewed as a rich source of traprock (basalt) by quarrymen seeking to provide building material for the growth of nearby Manhattan Island. By the early 1900s, development along the lower Hudson River had begun to destroy much of the area's natural beauty. The Commission was authorized to acquire land between Fort Lee, New Jersey, and Piermont, New York; its jurisdiction was extended to Stony Point, New York, in 1906.

The Commission was expected to raise the funds needed for the acquisition of land from private sources. Needing at least $125,000, Perkins turned first to J. P. Morgan, who offered to put up the entire sum on the condition that Perkins would become a Morgan partner. Perkins agreed, with the immediate result that quarrying along the Palisades was stopped on December 24, 1900.

Then, in 1908, the State of New York announced plans to relocate Sing Sing Prison to Bear Mountain. Work was begun and in January 1909, the state purchased the 740 acre (3.0 km²) Bear Mountain tract. Conservationists, inspired by the earlier work of the Park Commission, lobbied successfully for the creation of the Highlands of the Hudson Forest Preserve. However, the prison project was continued.

Working with Union Pacific Railroad president Edward Henry Harriman and (after Harriman's death) with his widow, Mary Averell Harriman, Perkins, arranged a gift to the state of ten thousand acres (40 km²) and one million dollars from the Harrimans toward the creation of a state park. Another $1.5 million was raised from a dozen wealthy contributors including John D. Rockefeller and Morgan. New York state appropriated a matching $2.5 million. Bear Mountain-Harriman State Park became a reality in 1910 when the prison was demolished. Perkins hired Major William A. Welch as Chief Engineer, whose work for the park would achieve national influence as state and national park systems grew. The Perkins Memorial Tower at Bear Mountain State Park commemorates his work for the park; the view from the tower takes in four states and the Hudson River valley, including New York City.

Perkins died on June 18, 1920. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City.[7]

Wave Hill House

In 1903, George W. Perkins purchased Wave Hill House in Riverdale, Bronx on the East side of the Hudson. He had been accumulating properties since 1895 to create a great estate along the river, including Oliver Harriman's adjacent villa on the site of what is now Glyndor House. Perkins planned the grounds to enhance the property's beautiful river views and added greenhouses, a swimming pool, terraces and the recreational facility; rare trees and shrubs were planted on the lawns, and gardens were created to blend with the natural beauty of the Hudson highlands. The property is now Wave Hill, a public botanical garden and cultural center.

See also

References

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. XV. James T. White & Company. 1916. pp. 33–34. Retrieved December 19, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ↑ George Walbridge Perkins yourdictionary.com

- ↑ John A. Garraty, Right-hand Man: the life of George W. Perkins (1978) p. 216

- ↑ Garraty, Right-hand man: the life of George W. Perkins (1978) p 302

- ↑ "Rejects Perkins For Food Board" in NYT on September 8, 1917

- ↑ "Perkins Rejected; Mitchell Chosen" in NYT on October 3, 1917

- ↑ "George W. Perkins". New York Times. June 19, 1920. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

There will be public sorrow as there is a public loss in the untimely death of George Walbridge Perkins before he reached his sixtieth year. His career was one of devotion to the service of the State and the country.

Further reading

- Cole, Marena. "A Progressive Conservative": The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive Party Campaign of 1912" (PhD dissertation, Tufts University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2017. 10273522).

- Garraty, John A. Right Hand Man: The Life of George W. Perkins, (1960) online

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. (1946) focus on 1912

- Myles, William J., Harriman Trails, A Guide and History, The New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, New York, N.Y., 1999.