- (center) A vacuum tube with a flashed getter coating on the inner surface of the top of the tube.

- (left) The inside of a similar tube, showing the reservoir that holds the material that is evaporated to create the getter coating. During manufacture, after the tube is evacuated and sealed, an induction heater evaporates the material, which condenses on the glass.

A getter is a deposit of reactive material that is placed inside a vacuum system to complete and maintain the vacuum. When gas molecules strike the getter material, they combine with it chemically or by absorption. Thus the getter removes small amounts of gas from the evacuated space. The getter is usually a coating applied to a surface within the evacuated chamber.

A vacuum is initially created by connecting a container to a vacuum pump. After achieving a sufficient vacuum, the container can be sealed, or the vacuum pump can be left running. Getters are especially important in sealed systems, such as vacuum tubes, including cathode ray tubes (CRTs), vacuum insulating glass (or vacuum glass)[1] and vacuum insulated panels, which must maintain a vacuum for a long time. This is because the inner surfaces of the container release absorbed gases for a long time after the vacuum is established. The getter continually removes residues of a reactive gas, such as oxygen, as long as it is desorbed from a surface, or continuously penetrating in the system (tiny leaks or diffusion through a permeable material). Even in systems which are continually evacuated by a vacuum pump, getters are also used to remove residual gas, often to achieve a higher vacuum than the pump could achieve alone. Although it is often present in minute amounts and has no moving parts, a getter behaves in itself as a vacuum pump. It is an ultimate chemical sink for reactive gases.[2][3][4][5][6]

Getters cannot react with inert gases, though some getters will adsorb them in a reversible way. Also, hydrogen is usually handled by adsorption rather than by reaction.

Types

To avoid being contaminated by the atmosphere, the getter must be introduced into the vacuum system in an inactive form during assembly, and activated after evacuation. This is usually done by heat.[7] Different types of getter use different ways of doing this:

- Flashed getter

- The getter material is held inactive in a reservoir during assembly and initial evacuation, and then heated and evaporated, usually by induction heating. The vaporized getter, usually a volatile metal, instantly reacts with any residual gas, and then condenses on the cool walls of the tube in a thin coating, the getter spot or getter mirror, which continues to absorb gas. This is the most common type, used in low-power vacuum tubes.

- Non-evaporable getter (NEG)[8]

- The getter remains in solid form.

- Coating getter

- A coating applied to metal parts of the vacuum system that will be heated during use. Usually a nonvolatile metal powder sintered in a porous coating to the surface of the electrodes of power vacuum tubes, maintained at temperatures of 200 to 1200 °C during operation.

- Bulk getter

- Sheets, strips, wires, or sintered pellets of gas absorbing metals which are heated, either by mounting them on hot components or by a separate heating element. These can often be renewed or replaced.

- Getter pump or sorption pump

- In laboratory vacuum systems, the bulk NEG getter is often held in a separate vessel with its own heater, attached to the vacuum system by a valve, so that it can be replaced or renewed when saturated.[8]

- Ion getter pump

- Uses a high voltage electrode to ionize the gas molecules and drive them into the getter surface. These can achieve very low pressures and are important in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) systems.[8]

Flashed getters

Flashed getters are prepared by arranging a reservoir of volatile and reactive material inside the vacuum system. After the system has been evacuated and sealed under rough vacuum, the material is heated (usually by radio frequency induction heating). After evaporating, it deposits as a coating on the interior surfaces of the system. Flashed getters (typically made with barium) are commonly used in vacuum tubes. Most getters can be seen as a silvery metallic spot on the inside of the tube's glass envelope. Large transmission tubes and specialty systems often use more exotic getters, including aluminium, magnesium, calcium, sodium, strontium, caesium, and phosphorus.

If the getter is exposed to atmospheric air (for example, if the tube breaks or develops a leak), it turns white and becomes useless. For this reason, flashed getters are only used in sealed systems. A functioning phosphorus getter looks very much like an oxidised metal getter, although it has an iridescent pink or orange appearance which oxidised metal getters lack. Phosphorus was frequently used before metallic getters were developed.

In systems which need to be opened to air for maintenance, a titanium sublimation pump provides similar functionality to flashed getters, but can be flashed repeatedly. Alternatively, nonevaporable getters may be used.

Those unfamiliar with sealed vacuum devices, such as vacuum tubes/thermionic valves, high-pressure sodium lamps or some types of metal-halide lamps, often notice the shiny flash getter deposit and mistakenly think it is a sign of failure or degradation of the device. Contemporary high-intensity discharge lamps tend to use non-evaporable getters rather than flash getters.

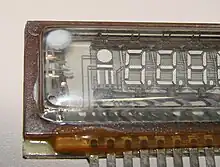

Those familiar with such devices can often make qualitative assessments as to the hardness or quality of the vacuum within by the appearance of the flash getter deposit, with a shiny deposit indicating a good vacuum. As the getter is used up, the deposit often becomes thin and translucent, particularly at the edges. It can take on a brownish-red semi-translucent appearance, which indicates poor seals or extensive use of the device at elevated temperatures. A white deposit, usually barium oxide, indicates total failure of the seal on the vacuum system, as shown in the fluorescent display module depicted above.

Activation

The typical flashed getter used in small vacuum tubes (seen in 12AX7 tube, top) consists of a ring-shaped structure made from a long strip of nickel, which is folded into a long, narrow trough, filled with a mixture of barium azide and powdered glass, and then folded into the closed ring shape. The getter is attached with its trough opening facing upward toward the glass, in the specific case depicted above.

During activation, while the bulb is still connected to the pump, an RF induction heating coil connected to a powerful RF oscillator operating in the 27 MHz or 40.68 MHz ISM band is positioned around the bulb in the plane of the ring. The coil acts as the primary of a transformer and the ring as a single shorted turn. Large RF currents flow in the ring, heating it. The coil is moved along the axis of the bulb so as not to overheat and melt the ring. As the ring is heated, the barium azide decomposes into barium vapor and nitrogen. The nitrogen is pumped out and the barium condenses on the bulb above the plane of the ring forming a mirror-like deposit with a large surface area. The powdered glass in the ring melts and entraps any particles which could otherwise escape loose inside the bulb causing later problems. The barium combines with any free gas when activated and continues to act after the bulb is sealed off from the pump. During use, the internal electrodes and other parts of the tube get hot. This can cause adsorbed gases to be released from metallic parts, such as anodes (plates), grids, or non-metallic porous parts, such as sintered ceramic parts. The gas is trapped on the large area of reactive barium on the bulb wall and removed from the tube.

Non-evaporable getters

Non-evaporable getters, which work at high temperature, generally consist of a film of a special alloy, often primarily zirconium; the requirement is that the alloy materials must form a passivation layer at room temperature which disappears when heated. Common alloys have names of the form St (Stabil) followed by a number:

- St 707 is 70% zirconium, 24.6% vanadium, and the balance iron.

- St 787 is 80.8% zirconium, 14.2% cobalt, and the balance mischmetal.

- St 101 is 84% zirconium and 16% aluminium.[9]

In tubes used in electronics, the getter material coats plates within the tube which are heated in normal operation; when getters are used within more general vacuum systems, such as in semiconductor manufacturing, they are introduced as separate pieces of equipment in the vacuum chamber, and turned on when needed. Deposited and patterned getter material is being used in microelectronics packaging to provide an ultra-high vacuum in a sealed cavity. To enhance the getter pumping capacity, the activation temperature must be maximized, considering the process limitations.[10]

It is, of course, important not to heat the getter when the system is not already in a good vacuum.

See also

References

- ↑ IGMA (FGIA) TB-2600; Vacuum Insulating Glass

- ↑ O'Hanlon, John F. (2005). A User's Guide to Vacuum Technology (3 ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 247. ISBN 0471467154.

- ↑ Danielson, Phil (2004). "How To Use Getters and Getter Pumps" (PDF). A Journal of Practical and Useful Vacuum Technology. The Vacuum Lab website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-02-09. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Mattox, Donald M. (2010). Handbook of Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) Processing (2 ed.). William Andrew. p. 625. ISBN 978-0815520382.

- ↑ Welch, Kimo M. (2001). Capture Pumping Technology. Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 0444508821.

- ↑ Bannwarth, Helmut (2006). Liquid Ring Vacuum Pumps, Compressors and Systems: Conventional and Hermetic Design. John Wiley & Sons. p. 120. ISBN 3527604723.

- ↑ Espe, Werner; Max Knoll; Marshall P. Wilder (October 1950). "Getter Materials for Electron Tubes" (PDF). Electronics. McGraw-Hill: 80–86. ISSN 0883-4989. Retrieved 21 October 2013. on Pete Miller's Tubebooks website

- 1 2 3 Jousten, Karl (2008). Handbook of Vacuum Technology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 463–474. ISBN 978-3-527-40723-1.

- ↑ "Nonevaporable getter alloys - US Patent 5961750". Archived from the original on 2012-09-11. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ↑ High-Q MEMS gyroscope

- Stokes, John W. 70 Years of Radio Tubes and Valves: A Guide for Engineers, Historians, and Collectors. Vestal Press, 1982.

- Reich, Herbert J. Principles of Electron Tubes. Understanding and Designing Simple Circuits. Audio Amateur Radio Publication, May 1995. (Reprint of 1941 original).