Gjura Stojana (also known as George Curtin Stanson, George Stojana, and George Stanley) (1885-1974)[1] was an American modernist painter and sculptor primarily identified with the Los Angeles-based modernist groups of the early 20th century.

Early life and move to the United States

Gjura Stojana was born in 1885.[2] Sources differ about his early life. According to the Laguna Art Museum, he was of Romani heritage, The Municipal Employee called him Serbian, and Lewis Mumford described his background as a mix of Latin and Slav.[3][4][5] Historian Edan Hughes gives his birthplace as France, while Mumford says he was born in Africa.[2][5] He moved to the United States in 1901 or 1903 and changed his name to George Curtin Stanson.[2] In 1908-09 he attended the San Francisco Art Institute and took a job writing about art for the San Francisco Chronicle.[6][2] When he was young, he traveled around Europe and Asia, which would greatly influence his work.[7]

Early career in Los Angeles and Hawaii

In 1917, he moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles. He formed a relationship with Elizabeth Rudolph, a teacher, with whom he lived at 3501 Dahlia Avenue in Los Angeles and had a child.[8] Stojana primarily produced abstract art, a style that does not try to faithfully depict reality. Abstraction was not yet popular in Los Angeles at the time, and according to friend and peer Conrad Buff, his work was not commercially successful at first so his family lived primarily on his wife's wages. Buff, who first knew Stojana as George Stanley and described him as "quite a character", praised his early work and regarded him as "the first abstractionist in Los Angeles".[9] He helped Stojana secure an exhibit at the Los Angeles Museum (which later split into the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, or LACMA, and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County), but when the show had to be pushed back by two weeks, Stojana said he would refuse to participate. Buff pled with Stojana to accept the delay for fear his "temperamental" reaction would cause the museum to think all modern painters were difficult. Stojana agreed, and then left to spend six months in Hawaii without his family.[9]

In Hawaii, he produced many works, including "Abundance", a large-scale painting which Arthur Millier described as "an expression of earthly richness painted in strong colors and massive Baroque design ... [representing] a large body of work done by Stojana in the islands".[10]

Return to Los Angeles

Stojana returned to Los Angeles in 1920, set up a home studio at 5653 La Miranda Avenue, and became involved with the local modernist art communities.[2] According to Laguna Art Museum curator Susan M. Anderson, Stojana was "omnipresent" among Los Angeles modernists, describing him as a "colorful and bohemian" and "a bridge" between the various regional modernist groups.[3] He was affiliated with the Modern Art Workers, which was founded in 1925 to exhibit work of artists that did not fit in with the most popular art trends at the time. The group also included Barbara Morgan, Buff, Mabel Alvarez, Morgan Russell, Edouard Vysekal, Henrietta Shore, Luvena Vysekal, and R. M. Schindler.[11][12] The organization held exhibitions at several Los Angeles locations, and Stojana served as president at some point in the 1920s. He was also close with photographers Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, Tina Modotti, and Johan Hagemeyer.[6][7] He was known on and off as George Stanson during this time, but changed his name back to Gjura Stojana, his birth name, in 1929.[2]

He was part of a movement which combined architecture and arts. Eleanor Lemaire, who was in charge of renovating the Bullocks Wilshire department store in downtown Los Angeles, hired him to paint a mural in the Sportswear Shop.[13] He created "Spirit of Sports" there in 1928, an Art Deco and Bauhaus-influenced fresco which incorporated plastic reliefs and wood strips.[14][6][10] Margaret Leslie Davis, author of a book about the store, described it as "an expression of action, speed and movement", praising it for its beauty.[14] While working on the piece, Stojana slept in the store.[6]

Stojana was well-traveled, and his work was frequently characterized as eclectic, combining influences of Western and Eastern artistic traditions.[5] Millier described a set of his tempera paintings as "reflecting a search for balanced movement suspended in a tranquility that reminds of the Orient".[10] A March 1923 article about Stojana by painter Francis Vreeland in Holly Leaves asked whether he was an "artist or freak, or both?". Vreeland described his affectations and personal appearance, questioning whether he might be a poseur, and wrote confusedly about the abstracted subjects in his work, which drew fans among modernists but caused "conservatives [to] shudder with horror [at] their various stages of 'ugliness, misshapenness, crudity, bad drawing and general nastiness!'" He included two quotes from Stojana: when asked why he chooses the subjects he does, Stojana responded "How do I know? I paint them"; when asked how he knows when he has finished a painting, he said "I never finish a picture -- I only complete one", which Vreeland said "might mean anything -- or nothing."[15]

Exhibitions

Going by George Curtin Stanson, Stojana exhibited at the New Mexico Museum of Art at least twice, first in 1917, the year the museum opened, and then in 1920.[16][2][17] The Art Institute of Chicago had an exhibit in 1926 combining Stojana's paintings, drawings, and woodcarvings inspired by "primitive idolmakers", alongside the work of Rene Menard and William Ritschel.[18]

He exhibited at the Los Angeles Museum several times, including exhibits in 1918, 1921, 1926, and in 1928.[12][2] The 1921 exhibition, a group show with Nick Briganti, Lawrence Murphy, Val Costello, and Edouard Vysekal, primarily featured the work he did in Hawaii.[19] The 1926 event was called the First Pan American Exhibition of Oil Paintings and included Stojana's "Bali - Ceremony of Cremation" as well as a portrait of Stojana by Clarence Hinkle.[20]

He had a solo exhibition at the California School of Fine Arts in March 1928, including his paintings and sculptures, that The Argus characterized as polarizing. While some reviewers have complimented the extent to which he integrated influences from Asian and Oceanic traditions, The Argus's editor, Jehanne Bietry Salinger, said that feature of his work could "[give] the impression, at first contact, that he is lacking in originality, that he is superficial and boldly aggressive in his faculty of adaptation" but went on to say this impression is dispelled when looking more closely to appreciate the expressive content. She described his woodcarvings, conversely, as beautiful works of original design rather than expressive."[21] The Municipal Employee described his work in the show as drawing "from sources in the South Seas, the Orient, and from his own theories of algebraic ornament, in still, rapid, and slow motion."[4] Later the same year, his work was included in a Hale Brothers Department Store traveling exhibition.[22]

Stojana's had at least four pieces, including both paintings and wood carvings, in a 1929 Stendahl Galleries exhibition alongside Buff, Edouard Vysekal, Hinkle, and Haldane Douglas. His work in the show, which occupied an entire gallery,[23] was positively received by Millier in the Los Angeles Times, who said he had "a rich gift able to turn in many directions".[10] In another write-up about the group show, Hollywood Hi-Lights said his "work never fails to provoke heated discussions among artist, critic and connoisseur alike".[24] Millier went on to say the wood carvings in the show "[gave] full play to the artist's powers of design, his feelings for the richness of life, and his matured plastic sense".[10]

In 1933 or 1934, Lewis Mumford wrote about his work at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City, praising his ability to fuse art techniques and styles from different parts of a world.[5] Mumford saw in his work Chinese-influence Picasso, Japanese-influenced Klee, and Congo-influenced Brancusi.[5]

Personal life and legacy

For most of his life, Stojana spent time in both Los Angeles and Santa Fe, New Mexico.[2] He was a member of the Archaeological Institute of America and the California Art Club.[2] His work is in collections at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County,[25] the Smithsonian Archives of American Art,[26] the Monterey Museum of Art,[27] the De Young Museum, the Museum of Archaeology in Santa Fe, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.[2]

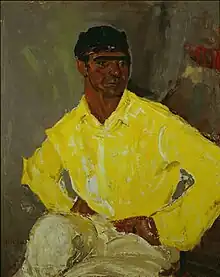

Multiple notable artists have made portraits of Stojana.[6] Mather and Weston photographed him several times in 1921 (one is at the Getty Museum, two others at the Center for Creative Photography),[28][29][30] Hagemeyer photographed him in 1930 (several of which are in a collection at the University of California Bancroft Library),[31] and Hinkle painted a portrait in 1925, which is considered one of Hinkle's best and was displayed at the Los Angeles Museum in 1927.[32][3][12]

He died in Los Angeles on September 16, 1974.[2]

References

- ↑ Hines, Thomas S. (2019). "Critic and Catalyst: Pauline Gibling Schindler (1893–1977)". Getty Research Journal. 11: 39–80. doi:10.1086/702748. ISSN 1944-8740.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hughes, Edan (2002). Artists in California, 1786-1940. Crocker Art Museum. ISBN 978-1884038082.

- 1 2 3 "Clarence Hinkle / Modern Spirit and the Group of Eight - Wall text panels from the exhibitions". tfaoi.org. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- 1 2 Hubbard, Anita Day (March 1929). "Of Interest to Women". The Municipal Employee – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mumford, Lewis (2007). Mumford on Modern Art in the 1930s. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 100–109. ISBN 9780520258082.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anderson, Susan M. "Modern Spirit: The Group of Eight & Los Angeles Art of the 1920s; essay by Susan M. Anderson - Clarence Hinkle's Portrait of Gjura Stojana and Bohemian Los Angeles". Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- 1 2 Albers, Patricia (2002). Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti. University of California Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780520235144.

- ↑ "USModernist". usmodernist.org. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- 1 2 Conrad Buff: Artist (PDF). University of California. 1968. pp. 91–95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Millier, Arthur (November 24, 1929). "Moderns and Mountains". Los Angeles Times – via Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Crosse, John (August 26, 2010). "Southern California Architectural History: Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad". Southern California Architectural History. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Blake, Janet. ""In Love with Painting" - The Life and Art of Clarence Hinkle; essay by Janet Blake". Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ↑ Crosse, John (August 26, 2010). "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad". Southern California Architectural History. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- 1 2 Davis, Margaret Leslie. "Bullocks Wilshire: The Genius Team Who Created Los Angeles' Famed Art Deco Masterpiece".

- ↑ Vreeland, Francis William (March 16, 1923). "Stanton Stojano, Artist or Freak, or Both?". Holly Leaves.

- ↑ "Dedication exhibit of Southwestern Art : Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe, November 24 to December 24, 1917". newm.ent.sirsi.net. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Exhibition of southwestern art : by a number of artists working in Santa Fe and Taos, September 1 to October 1, 1920". newm.ent.sirsi.net. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ↑ Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. 1926. p. 126.

- ↑ "Department of Fine and Applied Arts: Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Nick Briganti; Val Costello; Lawrence Murphy;… | California Revealed". californiarevealed.org. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ First Pan American Exhibition of Oil Paintings. Los Angeles Museum. 1925.

- ↑ Salinger, Jehanne Bietry (April 1928). "In San Francisco Galleries". The Argus. 3 (1): 127–128.

- ↑ Crosse, John (December 7, 2018). "Schindler-Scheyer-Eaton-Ain: A Case Study in Adobe". Southern California Architectural History. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Art and Artists". Los Angeles Times. November 24, 1929 – via Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ "Theatres / arts / doings". Hollywood Hi-Lights. February 1930 – via Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ "Seaver Center Collection Details | NHM". collections.nhm.org. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Record Stojana, Gjura | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Evening Light". Monterey Museum of Art.

- ↑ "George Stojana - Artist. (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection)". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ "eMuseum". ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ "eMuseum". ccp-emuseum.catnet.arizona.edu. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Finding Aid to the Johan Hagemeyer Photograph Collection, approximately 1908-1955". oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Clarence Hinkle, Gjura Stojana, 1925". Laguna Art Museum via YouTube. June 6, 2012.