| Golden Bust of Marcus Aurelius | |

|---|---|

_-_Mus%C3%A9e_romain_d'Avenches.jpg.webp) | |

| Material | Gold |

| Weight | 3.5 lbs |

| Created | 176-180 A.D. |

| Discovered | 1939 Avenches/Aventicum |

| Present location | The Getty Villa |

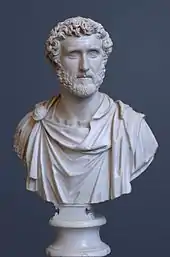

The Golden Bust of Marcus Aurelius is a golden bust of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius discovered on April 19, 1939 in Avenches, in western Switzerland. Measuring 33.5 centimetres (13.2 in) high and weighing 1.6 kilograms (3.5 lb), it is the largest known metal bust of a Roman emperor and is considered one of the most important archaeological finds in Switzerland. It is amongst six known golden busts made during the Roman Imperial Period.[1]

Discovered by chance during an excavation of the sewers of the Cigognier sanctuary in Aventicum, the bust is kept for security at the Banque cantonale vaudoise in Lausanne; a copy is on permanent display at the Roman Museum in Avenches. The original has only been exhibited a dozen times, including two exhibitions in Avenches, in 1996 and 2006. The bust is attributed to a goldsmith from the Aventicum region, although the rarity of ancient busts in precious metals prevents a clear analysis of its style.

Initially identified as the emperor Antoninus Pius, the bust is more frequently considered to represent his successor, Marcus Aurelius, in his old age. The identification of the bust, supported by the study of portraits of Roman emperors from period numismatics and emperors' busts, is not universally supported: the archaeologist Jean-Charles Balty believes that the bust represents the emperor Julian.

History

The gold bust was discovered on April 19, 1939 in Avenches by unemployed workers from Lausanne participating in an occupational program[N 1] organized by the association Pro Aventico which manages the city's ancient heritage. They were under the direction of the cantonal archaeologist Louis Bosset, the curator of the Roman Museum of Avenches Jules Bourquin and the scientific director of the site André Rais since October 21, 1938; their mission consisted mainly in revealing the outline of the building attached to the Cigognier column.[2] It was during the excavation of sewer number 1 of the site that a worker hit a metal object with his pickaxe; the bust was in a pipe, buried in silt and black earth, and was almost entirely covered with limestone. Weighing about 1.6 kilograms (3.5 lb) at the time of its discovery, the bust is the largest gold find made in Switzerland, and it was immediately registered by a notary.[3][4]

The bust was exhibited on the Cigognier site during the days following the discovery. The news spread very quickly across Switzerland, and the bust was moved to the bank every evening to prevent theft. Visitors came from all over the country to admire it, and newspapers from all over the world, such as The New York Times or The Illustrated London, wrote about it. Between August 21 and 26, 1939, the bust was exhibited in Berlin as part of the Sixth International Congress of Classical Archaeology.[5] It was loaned to the Kunsthaus in Zurich in the summer of 1939 before being sent to the Swiss National Museum for restoration. There, three plaster copies were produced for exhibitions at the Swiss National Museum, the Cantonal Monetary Museum in Lausanne, and the Roman Museum in Avenches.[6]

Before returning the bust to Avenches, the security arrangements at the Roman Museum in Avenches were evaluated at the request of the Department of Education and Religious Affairs. As they were deemed unsatisfactory, the copy was placed in the museum. The original was placed in the Banque cantonale vaudoise in Lausanne. This decision proved to be the right one, as two copies of the bust have since been stolen during burglaries, in November 1940 and July 1957.[7]

Since its loan to the Kunsthaus in Zurich, the original gold bust of Marcus Aurelius has only been exhibited on rare occasions: 1985 at the Schnütgen Museum in Cologne, 1991 at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, 1991-1992 at the History Museum in Bern, 1992 and 1996 at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire in Geneva, 1993-1997 at the Musée cantonal d'archéologie et d'histoire in Lausanne, 1995 at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, 2003-2004 at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, 2018 at the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne and 2023 at the Getty Villa in Malibu.[8][9][10] It was first shown at the Roman Museum in Avenches in 1996 for an exhibition called "Bronze and Gold", and was the centerpiece of the 2006 temporary exhibition.[8][11] A copy of the bust is part of the museum's permanent exhibition on the second floor.[12]

Place of discovery

The bust was discovered on the territory of Aventicum in the commune of Avenches. Located in the Broye-Vully District in the canton of Vaud, Avenches lies at an altitude of 478 metres (1,568 ft) on an isolated hill south of the Broye plain, 51 kilometres (32 mi) northeast of Lausanne and 29 kilometres (18 mi) southwest of Bern.[13][14] Aventicum is the ancestor of Avenches, and is located on the slopes of the Avenches hill.[14] During its heyday, in the first century AD, this Roman colony had a population of about 20,000 and was the administrative and political capital of Helvetii.[15] Aventicum is considered one of the richest archaeological sites in Switzerland and has been the subject of systematic excavations since the establishment of the Pro Aventico association in 1885.[16][15]

It was a dark time when our countryside experienced the threat and reality of invasion. The first two decades (260-280) were the most tragic: the first wave of the Alamanni invasion savagely swept across the Swiss plateau. Aventicum was ransacked. Numerous treasures buried just about everywhere as the barbarians approached bear silent but expressive witness to these savage raids.

Louis Meylan, Notre pays terre Romaine, 1929.[17]

The territory of Aventicum, which covers 228 hectares, includes a theater, bath-houses, an amphitheater and a temple.[15][18] The bust was found on the excavation site of the temple, called the "Cigognier sanctuary". A dendrochronological analysis of the foundation piles of the sanctuary dated its construction to 98 AD. While the emperor Vespasian had elevated Aventicum to the rank of colony 20 years earlier, the temple was probably built during the reign of Trajan.[19][15]

The site of Aventicum stands out among other similar archaeological sites for the presence of a large number of bronze artefacts. This has been attributed to the plundering of the city during an Alemanni invasion in the third century: many inhabitants, taken by surprise, did not have time to secure their belongings and hid them underground. Fires may have also contributed to the burial of precious objects.[20]

The name "Cigognier sanctuary" comes from a stork's nest on the only column still standing in the building. The name appeared for the first time in 1642, on an engraving by Matthäus Merian, and the nest was moved in 1978 during the restoration of the column.[19] Aventicum and Avenches take their name from the Celtic goddess Aventia (or Avencia).[21]

Manufacturing technique

Original

The bust was made from a single disk-shaped gold leaf, using the repoussé technique, although its size suggests that it could have been made from several leaves.[22][23] In 1940, the Swiss archaeologist Paul Schazmann stated that it was "[...] almost incredible that a work of this size should consist of a single sheet [...]".[22] This theory has often been questioned, but all the analyses carried out lead to the same conclusion.[24] It has not been melted either, as proven by its thinness; the bust was shaped by hammering, and its thickness varies according to the work at different points on its surface.[22][25] A tomographic analysis conducted in 2016 shows that the craftsman began his work with the narrowest part of the bust, the neck, and ended with the torso.[25] The bust is made from 92% 22-carat gold, and also contains 2-3% silver and 2-3% copper.[24][26] The bust has a total weight of 1,589.07 grams (56.053 oz) and a volume of 82.25 cubic centimetres (5.019 cu in).[25]

Copies

The first copies of the bust were produced in plaster in November 1939. The walls of these busts were 3 millimetres (0.12 in) thick, and the gilding was done with a leaf. A plaster copy dating from 1941, still on display at the Musée Monétaire Cantonal in Lausanne in 2006, was in a poor state of preservation and the red of the coating applied to the bust before gilding showed.[27]

A second series of copies was made in the 1970s in Betacryl resin. The longevity of these copies was questioned by Anne de Pury-Gysel, director of the work on the Aventicum site, because the decomposition of the busts over time created small black spots on the surface.[28] In 1992, new copies were made for the exhibition "The Gold of the Helvetians" in Zurich. Three models were created by electroplating, using a silicone mould.[29] Ten years later, the Vaud government realised that the mould was already in a state of decay. It therefore seemed crucial to produce a durable mould, so that if the original was lost, it would be possible to make copies. Walter Frei, curator at the National Museum in Zurich, is the author of this silicone 'print' made in 2003.[30]

Description

The bust is 33.5 centimetres (13.2 in) high and 29.46 centimetres (11.60 in) wide. The thickness of its wall varies between 0.24 and 1.4 millimetres (0.0094 and 0.0551 in), while its proportions are about three quarters of that of an adult male.[31][32]

The head of the bust is straight, and thus presents a symmetrical and rigid aspect not common to ancient busts, as marble busts are usually turned slightly to one side. A comparison with a bust of Marcus Aurelius kept in the Louvre Museum, especially at the eyebrows, shows that the gold bust would have been made in mirror image; its proportions are reversed from left to right.[33] The different parts of the bust are inspired by models from different periods, as shown, for example, by its narrowness, which recalls earlier works. The hair is short and wavy, a style dating from the first century AD and at odds with what is commonly known of Marcus Aurelius. The chin is slightly triangular, with a very round skull and a large forehead, whereas other statues of Marcus Aurelius present a more vertical and rectangular face.[34]

The bust represents an elderly and bearded man, with two horizontal wrinkles on the forehead and dark circles under the eyes.[35] The somber gaze of the bust projects a solemn expression that is most often found in posthumous works. The left eye is slightly higher than the right one, the nose has large nostrils and the mouth is narrow. The neck is smooth and does not show musculature or wrinkles. The body wears three layers of clothing, including a Roman cuirass with a Gorgon in the center and, on the left shoulder, a paludamentum originally held by a brooch, which has disappeared and must have been made of a precious stone.[36][35][37]

- Details of the bust[N 2]

Face

Face Gorgon and center of the cuirass

Gorgon and center of the cuirass Brooch missing from left shoulder

Brooch missing from left shoulder Profile view

Profile view Back of the head

Back of the head

At the time of its discovery, the bust presented several dents. A gash on his right cheek and a dent in the back of his head, corrected during the restoration of the bust, were probably inflicted during its excavation. Cracks in the back of the head and in the hair, a hole in the top and a torn off part under the left shoulder are of unknown origin.[35][38][39]

- Pre-discovery damage[N 2]

Fissures in the hair.

Fissures in the hair. Hole on the top of the head.

Hole on the top of the head. Part torn off under the left shoulder.

Part torn off under the left shoulder.

Interpretations

Identification

Soon after its discovery, the bust was identified as representing Antoninus Pius. Paul Schazmann, in 1940,noted a striking resemblance to Marcus Aurelius, the adopted son and heir of Antoninus.[40]

-CNG.jpg.webp)

In support to his conclusion, Schazmann concentrated his research on several Roman emperors, since gold could only be used for imperial representations at that time. He then studied the Roman coinage and ancient statues of emperors, although he knew that in the first century they did not yet have beards. Hadrian, Antoninus the Pious and Marcus Aurelius were the most likely candidates, although Hadrian was quickly discarded because of his physiognomic differences with the other two. Coins were a great help in identifying the bust; the Roman emperor was one of the few ancient figures to appear very frequently on imperial coins.[41]

The facial expression of the bust is similar to that found in reliefs of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Rome (built in 176), as well as in series of coins issued between 170 and 180.[42] Today, it is generally accepted that the bust represents Marcus Aurelius in the last years of his life. However, some differences with other known representations of Marcus Aurelius exist: apart from the different hairstyle, the top of the head is wider and lower than in other busts and in coins of the emperor. The date of production is assumed to fall between 176 and 180, but it cannot excluded that the bust is a posthumous work; a production after Marcus Aurelius' death would explain the hairstyle of the bust.[43][42][44]

This interpretatio is not unanimous.[43] In 1980, the French-Belgian archaeologist Jean-Charles Balty proposed a reinterpretation of the bust, arguing that it represents the 4th century AD Roman emperor Julian. Balty's conclusion is influenced by the statue's frontal gaze and its hairstyle.[45] Hans Jucker, a Swiss Classical Archaeologist, responded to Balty a year later by pointing out that the 'frontality' of the statue is explained by its use as the end of a staff and that the hairstyle of the bust is ultimately not similar to any known Roman emperor portrait, demonstrating local manufacture rather than a different identification. Jucker also pointed out that Julian was never depicted with wrinkles and that the way the eyes were reproduced did not match the typical style of the 4th century.[46]

According to Anne de Pury-Gysel, some commentators believe that the bust has been falsely attributed to antiquity; an alternative hypothesis dates the bust as a medieval work.[47][48] This idea probably arose from the fact that, until 1939, all the precious metal heads found dated from the Middle Ages. A certain resemblance, especially in the facial expression, to the Reliquary Bust of St. Candide in the Abbey of Saint-Maurice in Valais lends some credence to this theory, but their very different styles remove any possible doubt; ancient artists are known for their naturalistic portraits, with more realistic wrinkles and hair, while medieval portraits are generally simpler and more concerned with symbolism.[48]

Function and origin

The function of the bust cannot be defined with certainty. Since it cannot stand on its own, it was probably used mounted on a pole.[44] Three rivets made after the statue was created - one at the front, the other two on each shoulder - suggest that the pole was hidden by a cloth.[49] However, the context remains unclear; the American archaeologist Lee Ann Ricardi suggests that it was used as a war sign, but Aventicum is not known as a military town.[44][50] Another possible explanation is that the bust was used in celebrations, carried on a pole as a parade head, as depicted in a mural from the Roman villa at Meikirch, in the canton of Bern.[44][51]

The origin of the bust is often considered to be "provincial", i.e. probably from Avenches or the surrounding area.[52] Arguments in favour of this theory include its Celtic-style headdress, the fact that sources of gold were known in Helvetia in the first century AD and the existence of two goldsmiths - a father and son - in Aventicum at the same period, as attested by a funerary stele from the site.[52][53] As a result, the bust is sometimes stigmatised for its origin, often synonymous with poor quality as opposed to works from Rome itself. However, the lack of contemporary metalwork makes it impossible to determine the origin of the bust with any certainty.[52]

Reception and legacy

A copy of the bust was presented to Benito Mussolini by the head of the Department of Public Education in 1941 to thank him for his donations to the Vaud Cantonal Library. The gift was also made on behalf of the Council of State of Vaud and the Federal Council, in recognition of "the economic services that Mussolini [had just] rendered to Switzerland".[27]

In 1944, the former owner of the Cigognier plot claimed compensation for the gold bust from the Pro Aventico association. He based his claim on an easement that had remained in his name at the time of the sale and brought the case before the administrative court of the State of Vaud. Applying the Swiss Civil Code, the court declared the bust to be an "object of public interest", allowing it to become part of the State's collections.[4]

Archaeological finds of precious metals from Antiquity are rare, because most such artefacts were recycled into later works. The gold bust of Marcus Aurelius was the first ancient gold object ever found. For this reason, the local press called it "most important Roman object ever found in Switzerland".[54][55][56] It was followed in 1965 by the discovery, in Greece, of a 23-carat gold bust of Septimius Severus, and by various other artefacts, such as the head of a Roman statue in gold reused in the reliquary statue of Sainte Foy in Conques.[54][55] At 33.5 centimetres (13.2 in), the bust of Marcus Aurelius is also the largest of all Roman gold busts, larger than that of Septimius Severus by 5 centimetres (2.0 in) and of those of Licinius and Licinius II by more than 20 centimetres (7.9 in).[57]

In 2015, Swissmint issued commemorative coins to mark the 2,000th anniversary of Aventicum. The gold bust of Marcus Aurelius was chosen for the face of these coins. With a nominal value of 50 CHF, the coins are made of gold (90%) and copper (10%) and weight 11.29 grams (0.398 oz).[58][59]

References

Notes

References

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 477–493.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 21-22.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 25-26.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 29.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ "Marc-Aurèle joue les «guest stars» au Palais de Rumine". 24 heures (in French). 9 May 2018. ISSN 1424-4039. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ↑ "Trouvé à Avenches, le précieux buste antique de Marc Aurèle exposé à Los Angeles". rts.ch (in French). 2023-06-02. Retrieved 2023-06-06..

- ↑ "Aventicum - 2006 – Marc Aurèle". aventicum.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ↑ "Aventicum - Deuxième étage". aventicum.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ↑ "Avenches, la Broye-Vully, Vaud, Suisse". fr.db-city.com (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- 1 2 "Avenches (commune)". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- 1 2 3 4 "Aventicum - Histoire". aventicum.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ "Sites archéologiques visibles et invisibles". vd.ch (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ Schazmann 1940, p. 70.

- ↑ "Sanctuaire du Cigognier". Fribourg Région (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- 1 2 "Aventicum - Sanctuaire du Cigognier". aventicum.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ Schazmann 1940, p. 69-70.

- ↑ Yoland Gottraux (December 1988). "Faits historiques Avenchois" (PDF). commune-avenches.ch (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- 1 2 3 Schazmann 1940, p. 86.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 490-491.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 489.

- 1 2 3 de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 490.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel 2017, p. 36.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 41-42.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 45-47.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel 2017, p. 104.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 478.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 479.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 480.

- 1 2 3 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Schazmann 1940, p. 72.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 62.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 61.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 65-66.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 73-75.

- 1 2 Marc, Jean-Yves (2015). Theatres and Sanctuaries in the Roman World: réflexions à partir de l'exemple de Mandeure, in Agglomérations et sanctuaires. p. 296.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 Fuchs 2007, p. 313.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Jucker, Hans (1981). Marc Aurel bleibt Marc Aurel (in German). pp. 12–15.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Fuchs 2007, p. 311.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 51-53.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 93.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Suter, Peter (2004). "Meikirch, Villa romana, Gräber und Kirche [Photos de la peinture murale]". ADB Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern (in German): 100–101. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- 1 2 3 de Pury-Gysel & Brodard 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 485.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel 2017, p. 11.

- 1 2 de Pury-Gysel, Lehmann & Giumlia-Mair 2016, p. 477-478.

- ↑ "À quatre têtes". 24 Heures (in French). 1992-08-07. p. 11.

- ↑ de Pury-Gysel 2017, p. 101.

- ↑ "Le buste en or de Marc Aurèle, une découverte d'un intérêt exceptionnel" (PDF). swissmint.ch (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ↑ "50 Francs, Switzerland". en.numista.com. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

Works cited

- Balty, Jean-Charles (1980). "Le prétendu Marc-Aurèle d'Avenches". Antike Kunst (in French) (12): 57–63.

- Fuchs, Michel (2007). "Compte rendu de : Anne Hochuli-Gysel, Virginie Brodard, Marc Aurèle. L'incroyable découverte du buste en or à Avenches". Revue historique vaudoise (in French). 115: 311–314.

- de Pury-Gysel, Anne; Brodard, Virginie (2006). Marc Aurèle : l'incroyable découverte du buste en or à Avenches (in French). Avenches: Association Pro Aventico.

- de Pury-Gysel, Anne; Lehmann, Eberhard H.; Giumlia-Mair, Alessandra (2016). "The manufacturing process of the gold bust of Marcus Aurelius: evidence from neutron imaging". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 29 (29): 477–493. doi:10.1017/S1047759400072275. S2CID 113760503.

- de Pury-Gysel, Anne (2017). Die Goldbüste des Kaisers Septimius Severus (in German). Bâle: LIBRUM Publishers & Editors. ISBN 978-3-9524542-6-8.

- Riccardi, Lee Ann (2002). "Military standards, imagines, and the gold and silver imperial portraits from Aventicum, Plotinoupolis, and the Marengo treasure". Antike Kunst. 45: 86–100. ISSN 0003-5688. JSTOR 41321181. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- Schazmann, Paul (1940). "Buste en or représentant l'empereur Marc-Aurèle trouvé à Avenches en 1939". Revue suisse d'art et d'archéologie (in French) (2): 69–93.