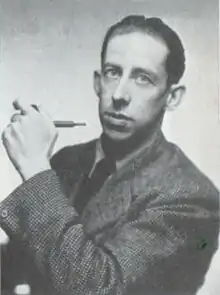

Jean-Pierre Gontran de Montaigne, vicomte de Poncins, known as Gontran De Poncins (August 19, 1900 – September 1, 1962), was a French writer and adventurer.

Life and works

Gontran de Poncins (a descendant of Michel de Montaigne) was the son of comte Bernard de Montaigne and of the countess, née Marie d'Orléans,[1] and was born on his family's nine-hundred-year-old estate in Southeast France.

Educated by clerics on the family estate until age fourteen, he followed the usual aristocratic path to military school and, finally, Saint Cyr, the French equivalent of West Point. World War I ended before he could enter the conflict, so he joined the army as a private (scandalizing his family, his widow reveals) and served with the French mission assigned to the American Army of Occupation of Germany. He grew increasingly interested in human psychology, searching, he said, for what is that helps people make their way through life. He joined the Paris École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts and painted there for six years, then entered an Italian silk concern and rose to become its manager in London.[2]

Bored with the business world, he became a freelance journalist so that he could travel, selling accounts of his experiences to newspapers and magazines.

Curiosity drew him to exotic areas throughout the world — Tahiti, New Caledonia, and, eventually (in 1938), the Canadian Arctic. What he discovered there, he believed, was a nobler way of life and, perhaps, a means of saving a fallen Western world. Initially, the lure of the Arctic for Poncins stemmed from a general disillusionment with civilization. [The trip resulted in] his popular Arctic travel narrative, Kabloona.... Although Poncins was French, the text was first published in the United States in English in 1941; the French edition followed six years later. In many ways, the book was primarily an American phenomenon. Upon his return from the Arctic, Poncins submitted well over a thousand pages of notes in French and English to an editor at Time-Life Books. The editor shaped the text into its published form, and Time-Life successfully marketed it to large American audiences. The French edition of Kabloona is a translation of the English Time-Life edition.[3]

He returned to wartime France in 1940, but rather than "shooting craps in the Maginot Line" he joined a U.S. Army paratrooper unit. He broke his leg in a bad jump and was assigned to a training unit for the duration.

"After World War II, finding his baronial estate looted, he wanted to start again, someplace far away. He sought out some of the famous lone explorers and visionaries of his day, including Teilhard de Chardin in China. It was after his last trip to China that he met up with his parents again. [They] were soon to die in their castle. He agreed to part with the estate in a financial arrangement that turned sour. He turned his back on the old aristocracy and on his childhood friends, who seemed obsessed with deer-stalking and duck-shooting parties."[4]

In 1955 he moved to the Sun Wah hotel in Cholon in South Vietnam, keeping an illustrated journal which was published as From a Chinese City (1957). "He chose Cholon, the Chinese riverbank community snuggled up to Saigon, because he suspected the ancient customs of a national culture endure longer in remote colonies than in the motherland. In effect, he was studying a bit of ancient China."[5] He spent his last years on a small estate in Provence, where his wife was from, and died in 1962.

References

- ↑ Henri Temerson, Biographies des principales personnalités françaises décédées au cours de l'an 1962 (chez l'auteur [13 bis rue Beccaria], 1962), p. 225

- ↑ About the author

- ↑ Shari Michelle Huhndorf, Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination (Cornell University Press, 2001: ISBN 0-8014-8695-5,), p. 116.

- ↑ Therizol de Poncins, the author's widow, quoted in About the author

- ↑ Product description