| Government Palace House of Pizarro | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neobaroque |

| Town or city | Lima |

| Country | Peru |

| Construction started | 1535 (first construction) 24 August 1937 (latest renovation) |

| Client | Government of Peru |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Most recent renovations: Claude Antoine Sahut Laurent (France); Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski (Poland) |

The Government Palace (Spanish: Palacio de Gobierno), also known as the House of Pizarro, is the seat of the executive branch of the Peruvian government, and the official residence of the president of Peru.[1] The palace is a stately government building, occupying the northern side of the Plaza Mayor in Peru's capital city, Lima. Set on the Rímac River, the palace occupies the site of a very large huaca ("revered object") that incorporated a shrine to Taulichusco, the last kuraka (indigenous governor) of Lima.

The first Government Palace was built by Francisco Pizarro, governor of New Castile, in 1535. When the Viceroyalty of Peru was established in 1542, it became the viceroy's residence and seat of government. The most recent alterations to the building were completed in the 1930s, under the direction of President Oscar R. Benavides during his second term of office. The chief architects were Claude Antoine Sahut Laurent and Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski.

A number of ceremonial guard units of the Peruvian Armed Forces are stationed at the palace, and participate in the daily Changing of the Guard ceremony and other official duties.

Architecture

The current Government Palace building dates largely from the 1920s. It is representative of the Neo-Plateresque style characteristic of Lima from the 1920s to the 1940s. The coat of arms of Pizarro is displayed on the main portico of the building, at Palacio Street, which was designed and built by the French architect Claude Antoine Sahut Laurent (1883–1932).

The Polish architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski designed the building's facade in 1938. Inspired by the Neo-Baroque style, it looks onto the main square, the Plaza Mayor, or Plaza de Armas, of Lima.

Interior

The palace has several formal rooms looking out onto a courtyard garden. The palace has several inner courtyards, and halls and rooms named for notable figures in Peruvian history.

The Presidential Office (Despacho Presidencial) is named in honor of Colonel Francisco Bolognesi. The Agreements Room is named for Admiral Miguel Grau. The Ministers' Council Room is named after Air Force Captain José A. Quiñones Gonzáles. The Ambassadors' Room (Salón de Embajadores) has recently been renamed in honor of the inspector of the guards Mariano Santos Mateo. Among the reception rooms is the Golden Hall, which has a fine collection of paintings. The building also contains elegant living quarters which serve as the official residence of the president of the republic.

Jorge Basadre Room

Previously called the Eléspuru and Choquehuanca Hall (Hall Eléspuru y Choquehuanca), the Jorge Basadre Room (Salón Jorge Basadre) is in the Spanish Renaissance style and dates from the 1920s. It features marble columns and rounded arches showing Moorish architectural influence. The hall is illuminated by four large windows, and the floor is Italian marble mosaic. Two presidential carriages, used on official occasions until 1974, are displayed in this room.

The room may be entered through from a door to the palace on Palacio Street. Its original name paid tribute to the soldiers who died defending the building here during the attack on 29 May 1909 during the first presidency of Augusto B. Leguía, whose bust is displayed beneath a portrait of Pedro Fernández de Castro, Count of Lemos by an unknown 17th century artist.[2]

Sevillian Patio

This internal courtyard, dating from the 1920s, features glazed tiles made in Seville, Spain. Each set displays the coat of arms of Peru, of Lima, and Pizarro. It is accessed through the rooms of the presidential residence.[3]

One legend says that Pizarro himself planted and took care of a fig tree here that is supposedly alive today.[4] According to the Peruvian historian Raúl Porras Barrenechea, the fig tree was "not mentioned by any chronicler of the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries until it was invented by some valet from the palace, urged by tips".[5]

Golden Hall

Dating from the 1920s, the Golden Hall (Salón Dorado) is the largest and grandest of the Government Palace. It is the main reception hall, and is where ministers take their oath of office and ambassadors present their credentials to the president.

Inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles in France, the room is the work of the French architect Claude Antoine Sahut Laurent. The walls feature tall mirrors and relief work in gold leaf. The vaulted ceiling is decorated with gilded relief work featuring both indigenous and European motifs. The furnishings are in the style of Louis XIV; four bronze and crystal chandeliers hang from the ceiling. The room contains two matching marble tables, and an old clock topped with a small statue of Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, who was victorious at the Battle of St. Quentin in 1557. In the central part of the hall is a marble dais and balustrade, framed by two double columns with gilded bronze capitals, each carved from a single block of pink marble.[6]

Túpac Amaru II Room

This room dates from the 1920s. The Túpac Amaru II Room (Salón Túpac Amaru), renamed from the Pizarro Room in the 1970s during the presidency of Juan Velasco Alvarado, is furnished in the Neo-Colonial style. A central rotunda features a wooden cupola with a stained glass lamp at its highest point. The room features four sculptures by Mateu, an artist of French origin, representing the seasons, and plaster reliefs by Daniel Casafranca representing the Incas. The large portrait of Peruvian rebel Túpac Amaru II hanging over the carved wooden fireplace replaced in 1972 the portrait of Pizarro that hung in this room. On display is a throne that was a gift of the Japanese Emperor Akihito to Peru. This was the first official dining hall of the Government Palace, and could seat 172 people.

This is the room from which the president addresses the nation. It is also used for press conferences, meetings and, occasionally, as a dining room.[7]

Peace Room

This room is named to commemorate the signing of a peace treaty between Honduras and El Salvador on 30 October 1980. The president of Peru, José Bustamante y Rivero, acted as mediator.[8]

Designed by Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, the Peace Room (Spanish: Salón de la Paz) is also known as the great dining hall of the Government Palace (Spanish: Gran Comedor). It is one of the largest rooms in the palace, with a seating capacity of 250. The room is colonial in style, and features carved wooden beams and two balconies where chamber orchestras can perform. From the ceiling hangs a quartz crystal chandelier made in Bohemia, weighing some 2,000 kg (4,400 lb). Also of note are the length of the table and the leather backs of the carved chairs, stamped in gold with Pizarro's shield. The chairs are upholstered in different colors for men and women. Paintings by Abraham Brueghel (Flemish, 17th century) and Girolamo Cenatiempo (Italian, 18th century) hang in this room.[9]

Admiral Miguel Grau Room

A painting of the naval hero, Admiral Miguel Grau, hangs in this room, which was previously called the Agreements Room.

The room also contains a dark wood fireplace, decorated with a maquette of the turret ship Huáscar, built for Peru in Britain in the 1860s.

Ambassadors' Room

The Ambassadors' Room (Salón de Embajadores) bears its name because it is the room where ambassadors deliver credentials to the president. Its wooden and bronze decor is in the Louis XIV style, and its furniture is Regency.

Great Hall and presidential residence

The Grand Entrance (Puerta de Honor) of the Government Palace leads into the two-level Great Hall (Gran Hall). Above the door hangs a painting of Francisco Pizarro by Daniel Hernández. This painting hung in the Pizarro Room until 1972. The hall is lined with Roman-style columns, decoration in bronze leaf and painted stucco relief. The marble floor displays indigenous motifs. The staircase at the end of the hall is framed by two busts of the Liberators of Peru Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, sculpted by Peruvian artist Luís Agurto. The busts in the gallery of important figures in Latin American history were made by sculptor Miguel Bacca Rossi. Above the stairwell, a domed ceiling features Art Nouveau-inspired stained glass. The white stucco-decorated gallery on the second level of the Great Hall gives access to the office of the Council of Ministers (Consejo de Ministros).[3]

The living quarters of the president and their family in the Government Palace, dating from 1838, are accessed through the Great Hall. The residential quarters feature several important rooms, and the Seville Patio.[3]

History

New Castile

Francisco Pizarro, appointed Governor of New Castile in 1529, founded the city of Lima as his capital in 1535 and built his palace on its Plaza Mayor in 1536. The original house was a two-story adobe structure, built on the Castilian model with two large courtyards for troops and stables. It stood on the site of a large huaca ("revered object") where Taulichusco, last kuraka, or indigenous ruler, of the Rimac Valley during that period, had lived until Pizarro's conquest of the area. Present-day Lima is built over the location of more than 300 sacred huaca sites, of which this was one of the most important.[10]

The building served as the head office of Pizarro's administration. On Sunday 26 June 1541, thirteen supporters of Diego de Almagro II, whose father Diego de Almagro had been executed in 1538 by Pizarro's brother Hernando, stormed the building. Several guests escaped as the attackers fought their way in, but four defenders were killed and four wounded before Pizarro was assassinated.[11]

Viceregal period

Following Pizarro's death in 1541, and the creation of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1542, the building became the Viceregal Palace. It underwent several extensions over the course of this period, and was occupied by 43 viceroys before the last, José de la Serna, was forced out in 1821.

The building was damaged by an earthquake on 20 October 1687, and again in 1746.[12] Antonio de Ulloa described the building as it was at the time of his arrival in Lima as a young lieutenant of the Spanish Navy in 1740:

In the north side of the square is the vice-roy's palace, in which are the several courts of justice, together with the offices of revenue, and the state prison. This was formerly a very remarkable building, both with regard to its largeness and architecture, but the greatest part of it being thrown down by the dreadful earthquake with which the city was visited, Oct. 20th, 1687, it now consists only of some of the lower apartments erected on a terras [sic], and is used as the residence of the vice-roy and his family.[13]

General José de San Martín declared the independence of Peru from the palace on 28 July 1821.

Republican period

The Government Palace has served as the seat of government of all presidents of the Republic of Peru since the viceroyalty came to an end.

Fire gutted the building in December 1884, during the presidency of General Miguel Iglesias, and it had to be rebuilt.

In 1921, fire again destroyed much of building. The then president, Augusto B. Leguía, ordered its reconstruction and, in modifying the facade, launched the building of the present Government Palace.

Work began in 1926. The first phase was designed by the French architect Claude Antoine Sahut Laurent (1883–1932). Construction came to a halt with his death in 1932. Phase II was built between 1937 and 1938 during the presidency of Oscar R. Benavides, who assigned completion of the building to the Polish architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski. Work began on 24 August 1937 with the demolition of the older structure, including what remained of Pizzaro's original adobe building. The project was completed the following year, when the new Government Palace was officially inaugurated.

On 28 July 2021, during his inauguration, President Pedro Castillo announced that he will not govern from the palace and that the palace will be handed over to the Ministry of Cultures and turned into a museum of Peruvian history.[14]

Palace Guard

Viceregal Period

When the viceroyalty was established, the Viceregal Palace Guards were the Halberdier Corps of the Viceroy's Royal Infantry Guard (Compañía de Alabarderos de la Guardia Real de Infantería del Virrey).

Antonio de Ulloa described the Viceroy's bodyguard in 1740:

"For the safety of his person and the dignity of his office, he has two bodies of guards; one of horse, consisting of 160 private men, a captain and a lieutenant. Their uniform is blue, turned up with red, and laced with silver. This troop consists entirely of picked men, and all Spaniards... These do duty at the principal gate of the palace; and when the viceroy goes abroad he is attended by a piquet guard consisting of eight of these troopers. The 2d is that of the halberdiers, consisting of 50 men, all Spaniards, dressed in a blue uniform, and crimson velvet waistcoats laced with gold. These do duty in the rooms leading to the chambers of audience, and private apartments. They also attend the viceroy when he appears in public, or visits the offices and tribunals."[15]

The Royal Halberdiers were the Viceroy's Guard for three hundred years until the Latin American wars of independence of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Republican period

The Peruvian Army was charged with protection of the Government Palace from 1821. Various army units stationed at the palace also performed public duties. This role was shared from 1852 with the Peruvian National Gendarmerie (Gendarmería Nacional del Perú). From 1873, they were joined by the Civil Guard (Guardia Civil).

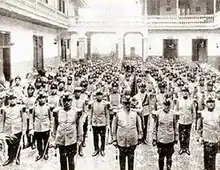

President Augusto Bernardino Leguía Salcedo, then in his second term of office, permanently assigned an infantry battalion to safeguard palace security and assume public duties on the model of the French Republican Guard, on the insistence of Peruvian Army General Gerardo Álvarez. The First Gendarme Infantry Battalion, later renamed 1st Republican Guard of Peru Infantry Gendarme Battalion of the Peruvian National Gendarmerie, was appointed presidential guard battalion by Presidential Decree of 7 August 1919.[16] Florentino Bustamante was its first commanding officer, serving until 1923. The Guard Battalion was mandated to ensure security in all national government buildings, in particular of "the Government Palace and the National Congress". The battalion grew to become a full regiment, and moved to new barracks at the Quinta de Presa palace in 1931.

Also in 1931, the Republican Guard Regiment was renamed the 2nd Infantry Regiment of Security under the government of President David Samanez Ocampo, in a failed attempt to unify the national police services following the example of Chile. It reverted to its former name later that year at the order of President Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro. The regiment underwent a new reorganization in 1932, with a new motto: "Honor, Loyalty, Discipline". It remained the presidential guard until shortly after the assassination of President Sánchez Cerro on 30 April 1933. The reorganized regiment comprised a regimental headquarters unit, service battalion, and two battalions of three rifle companies each, plus a machine gun platoon, the regimental band and drum corps.

The role of the guard was expanded in 1935 to include border patrol, prison security, protection of public and private places of national importance, and general maintenance of peace, public order and national security, in addition to fighting alongside the armed forces in times of war. With the expansion of its role, the Guard left palace duties in 1940.

Responsibility for the security of the president and Government Palace was taken over in that year by the Palace Machine Gun Detachment of the Civil Guard (Destacamento de Ametralladoras de Palacio). From 1944 to 1969, it continued in that role as the 23rd Command of the Civil Guard - Palace Machine Guns (23ª Comandancia de la Guardia Civil – Ametralladoras de Palacio). It was reorganized into a police unit in 1969, and was succeeded by the Assault Battalion of the 22nd Command of the Civil Guard (22ª Comandancia de la Guardia Civil del Perú - Batallón de Asalto). In 1987, protection of Presidential security was assumed by the 501st Military Police Battalion of the Peruvian Army (Batallón de Policía Militar Nº 501).

Today the Government Palace Guard performs largely ceremonial public duties for its commander in chief, the president, and his family on behalf of the Armed Forces and the National Police of Peru. Palace security is assured by the personnel of the Presidential Security Division, the State Security Directorate and the Civil Disturbance Directorate of the National Police.

Horse Guard

The "Mariscal Domingo Nieto" Cavalry Regiment Escort (Regimiento de Caballería "Mariscal Nieto" Escolta del Presidente de la República del Perú) is the Horse Guard of the Government Palace. Other than the period from 1987 to 2012, it has served in that role since it was first raised in 1904.

Modeled on the French dragoon regiments of the late 19th to early 20th centuries, this cavalry regiment was formed on the recommendation of a French military mission to Peru that, in 1896, undertook a reorganization of the Peruvian Army. Originally known as the Presidential Escort Cavalry Squadron (Escuadrón de Caballería "Escolta del Presidente"), it was granted regimental status in 1905, and was named after Field Marshal Domingo Nieto in 1949.

In 1987, President Alan García replaced the Dragoons with the "Glorious Hussars of Junín - Liberator of Peru" Cavalry Regiment (Regimiento de Caballería "Glorioso Húsares de Junín" N° 1 - Libertador del Perú, or Húsares de Junín) as the Presidential Life Guard, a position it held until 2012. The Junín Hussars were raised in 1821 by José de San Martín as part of the Peruvian Guard Legion, and fought in the final battles of the Latin American wars of independence in Junin and Ayacucho. Wearing uniforms similar to the Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers "General San Martín," but in red and blue with a shako, the Hussars carry sabers and lances on parade, both mounted and on foot. They were transferred to the Army Education and Doctrine Command in 2012 after 25 years of service, but the regiment still rides to the palace and in state ceremonial events when required.

The Domingo Nieto Regiment was reactivated on 2 February 2012, by order of President Ollanta Humala and the Peruvian Ministry of Defense. It now joins the other guard units stationed at the Government Palace, and alternates with them in the palace grounds. Today, it serves as the Peruvian equivalent, with the Junín Hussars Regiment and the Mounted Squadron of the Chorrillos Military School Cadet Corps, of the British Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment.

Changing of the Guard

The Changing of the Guard is a major tourist attraction at the Government Palace. It takes place at noon daily on the main esplanade looking onto the Plaza de Armas. There dedicated stands outside the palace for public viewing.

Schedule of ceremonies

On the first and third Sundays of the month the Dragoon Guards of the Presidential Life Guards Regiment "Mariscal Nieto" conducts a formal mounted Changing of the Guard ceremony in the presence of the president of the republic and first lady or, traditionally, in their absence, of the chief of the Presidential Military Staff. From 2014, government ministers have been authorized to preside over the formal ceremony.

On other days, the Changing of the Guard is performed unmounted. On Saturdays, and on the 2nd and 4th Sundays of the month, the unmounted ceremony mirrors that of the mounted Dragoon Regiment, but includes a drill exhibition with band accompaniment. Unlike the Dragoon Regiment, which performs a slow march during the Monday and Friday ceremonies, the other units make their entrance with a quick march.

In addition to the Changing of the Guard, the Dragoons, and other ceremonial units of the Armed Forces, perform the daily public raising of the flag at 8:00 pm and lowering of the flag at 6:00 pm.

Participating units

In 2007, President Alan Garcia ordered participation in the ceremony to be opened to all of the Armed Forces and the National Police, represented by their historical and ceremonial units. The Peruvian Navy's Fanning Marine Company (Compañía de Infantería de Marina Capitán de Navío AP Juan Fanning García) joined the ceremonial footguards of the palace at that time, participating in alternation with the Junín Hussars and the Peruvian Guard Legion Infantry Battalion. In 2012, after a five-year absence, the ceremonial unit of the Peruvian Air Force, the Airborne Platoon of the 72nd Squadron, resumed participation in the Changing of the Guard, as did the Peruvian Air Force Central Band.

Mounted ceremony

The mounted Changing of the Guard begins with the regimental band trotting past the dignitaries at the palace entrance and taking position on the esplanade. Three mounted officers from the regiment then approach the palace entrance at a trot as the band plays La Rejouissance from George Frideric Handel's Royal Fireworks Suite. They give notice that the changing of the guard is about to begin, and if the president is present the officers salute to the accompaniment of Sergeant Major José Sabas Libornio Ibarra's 1897 Marcha de Banderas (March of Flags). The commencement of the ceremony is called, a fanfare is sounded and they trot to take their place as the band plays. Two mounted officers arrive at the gate and canter past the president. The music stops, the officers face the front and draw their sabers. The guard detail commander, an officer of field rank, calls the regimental troops and salutes, with the executive officer as second in command. To band accompaniment, the color guard and guidon escort guard trot into the palace square, followed by the platoons led by their officers.[17] These are the Old and New Guards. The music stops, the officers face the front, call a full salute and inform the president of the commencement of the Musical Ride. Following the salute, as the commander of the New Guard orders the end of the salute, the band strikes up and the mounted platoons parade in the presence of the president. The ride ends with the troops forming in parade order and walking past the president, bringing the ceremony to a close, followed by the trot past of the band.

When the president is not in attendance, only the leading officer makes the initial salute, and the official march is not played. In place of the platoons' salute to the president, the band sounds a fanfare as the Old and New Guards salute each other. The Musical Ride concludes with the guards trotting out, and is followed by another exhibition by the Chorrillos Military School and the Army Cavalry and Equestrian School's mounted units.

The Presidential Escort Regiment parades in full dress uniform, consisting of white tunics with red pants in summer, and blue breeches in winter. Epaulettes, similar to French practice, are gold for officers and red for non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel. A gold pith helmet is worn, bearing the coat of arms of Peru, and the dragoons are armed with sabres and lances. Formerly the FN FAL rifle, standard issue in the Peruvian Army, was part of the regiment's arsenal, but only used in dismounted drill. In 2013, bass drums, suspended cymbals, and snare drums were added to the instruments of the mounted band.

See also

- Casa Suárez, a building whose façade is based on the Government Palace

- Palacio de la Magdalena, seat of the collaborationist government of the War of the Pacific

References

- ↑ "Government Palace".

- ↑ comunidadperuana.com, ed. (2002). "Hall Pedro Potenciano Choquehuanca y Eulogio Eléspuru Deustua" [Pedro Potenciano Choquehuanca and Eulogio Eléspuru Deustua Hall] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 comunidadperuana.com, ed. (2002). "Gran Hall" [Great Hall] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "Historia de Palacio". Government of Peru (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ Porras Barrenechea, Raul (1965). "Pequeña antología de Lima; El río, el puente y la alameda". Fondo Editorial Unmsm. Lima, Peru: 377.

- ↑ comunidadperuana.com, ed. (2002). "Golden Hall" [Salón Dorado] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ comunidadperuana.com, ed. (2002). "Salón Túpac Amaru" [Túpac Amaru Room] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ AFP (2011). "Un tratado de paz en medio de otra guerra" [A Peace Treaty in the Middle of Another War]. El Diario de Hoy (in Spanish). San Salvador, El Salvador. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ comunidadperuana.com, ed. (2002). "Gran Comedor" [Great Dining Hall] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ AFP (30 April 2012). "Las huacas, lugares sagrados de antiguos peruanos, en peligro de extinción" [Huacas, the Sacred Sites of the Ancient Peruvians, in Danger of Disappearing] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ Sancho, Pedro (July 1872). "Chapter 4: Report on the Distribution of the Ransom of Atahuallpa, Certified by the Notary Pedro Sancho". In Markham, Clements R. (ed.). Reports on the Discovery of Peru - Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society - First Series N° XL VII-MDCCCLXXII. Translated by Markham, Clements R. Burt Franklin, New York. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Walker, Charles F. (1 February 2003). "The Upper Classes of Peru and their Upper Stories: Aftermath of the Lima Earthquake of 1746". Hispanic American Historical Review. 83 (1): 53–82. doi:10.1215/00182168-83-1-53. S2CID 144925044. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ de Ulloa, Antonio (1806). "Chapter 2: Account of the City of Lima". A Voyage to South America: Describing at Large the Spanish Cities, Towns, Provinces, &c. on that Extensive Continent: Undertaken, by Command of the King of Spain, Volume 2. Translated by Adams, John. J. Stockdale. p. 32. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Leftwing rural teacher Pedro Castillo sworn in as president of Peru". the Guardian. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ↑ de Ulloa, Antonio (1806). "Chapter 2: Account of the City of Lima". A Voyage to South America: Describing at Large the Spanish Cities, Towns, Provinces, &c. on that Extensive Continent: Undertaken, by Command of the King of Spain, Volume 2. Translated by Adams, John. J. Stockdale. p. 41. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Article 1 of Supreme Decree of 7 August 1919 reads: "The 1st and 2nd Gendarme Battalions shall have the regimental organization of an army corps, with its current budget, and shall now be called the " Republican Guard ", commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel, with 27 officers and 431 individuals of all ranks, divided into 2 companies of 2 battalions each, 1 machine gun company and a headquarters military band."

- ↑ TV Perú Noticias - video report (25 February 2018). "Cambio de Guardia Montada en Palacio de Gobierno" [Mounted Changing of the Guard at Government Palace]. Andina – Agencia Peruana de Noticias (in Spanish). Peru. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Guides to Perú – Lima by Victor W. Von Hagen, Third Edition, 1960, pages 8,9 and 18.

- Caminante Magazine of Ecology and Tourism Nº 12, 1995, Essay: Behind the Government Palace House's threshold by Juan Puelles, pages 13–14.

External links

Gallery

Main Square of Lima with the Palace of the Viceroys in the epoch of the Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Junient (1772-1776)

Main Square of Lima with the Palace of the Viceroys in the epoch of the Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Junient (1772-1776) Palace of the Viceroys in the 18th century

Palace of the Viceroys in the 18th century Government Palace of Peru in 1860

Government Palace of Peru in 1860 Government Palace of Peru in 1865

Government Palace of Peru in 1865 Government Palace of Peru in 1895's revolution

Government Palace of Peru in 1895's revolution Government Palace of Peru in the late 19th century

Government Palace of Peru in the late 19th century Interior of the Government Palace of Perú in 1921

Interior of the Government Palace of Perú in 1921 Peru's Government Palace in 1938

Peru's Government Palace in 1938 Facade of the Peru's Government Palace facing onto the Main Square

Facade of the Peru's Government Palace facing onto the Main Square Porch of the facade of the Government Palace facing onto the Main Square

Porch of the facade of the Government Palace facing onto the Main Square View from the Archbishop's Palace

View from the Archbishop's Palace Frontal view

Frontal view Detail of the facade

Detail of the facade.jpg.webp) Night view

Night view