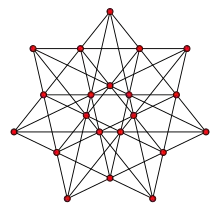

In geometry, the Grünbaum–Rigby configuration is a symmetric configuration consisting of 21 points and 21 lines, with four points on each line and four lines through each point. Originally studied by Felix Klein in the complex projective plane in connection with the Klein quartic, it was first realized in the Euclidean plane by Branko Grünbaum and John F. Rigby.

History and notation

The Grünbaum–Rigby configuration was known to Felix Klein, William Burnside, and H. S. M. Coxeter.[1] Its original description by Klein in 1879 marked the first appearance in the mathematical literature of a 4-configuration, a system of points and lines with four points per line and four lines per point.[2] In Klein's description, these points and lines belong to the complex projective plane, a space whose coordinates are complex numbers rather than the real-number coordinates of the Euclidean plane.

The geometric realisation of this configuration as points and lines in the Euclidean plane, based on overlaying three regular heptagrams, was only established much later, by Branko Grünbaum and J. F. Rigby (1990). Their paper on it became the first of a series of works on configurations by Grünbaum, and contained the first published graphical depiction of a 4-configuration.[3]

In the notation of configurations, configurations with 21 points, 21 lines, 4 points per line and 4 lines per point are denoted (214). However, the notation does not specify the configuration itself, only its type (the numbers of points, lines, and incidences). It also does not specify whether the configuration is purely combinatorial (an abstract incidence pattern of lines and points) or whether the points and lines of the configuration are realizable in the Euclidean plane or another standard geometry. The type (214) is highly ambiguous: there is an unknown but large number of (combinatorial) configurations of this type, 200 of which were listed by Di Paola & Gropp (1989).[4]

Construction

The Grünbaum–Rigby configuration can be constructed from the seven points of a regular heptagon and its 14 interior diagonals. To complete the 21 points and lines of the configuration, these must be augmented by 14 more points and seven more lines. The remaining 14 points of the configuration are the points where pairs of equal-length diagonals of the heptagon cross each other. These form two smaller heptagons, one for each of the two lengths of diagonal; the sides of these smaller heptagons are the diagonals of the outer heptagon. Each of the two smaller heptagons has 14 diagonals, seven of which are shared with the other smaller heptagon. The seven shared diagonals are the remaining seven lines of the configuration.[5]

The original construction of the Grünbaum–Rigby configuration by Klein viewed its points and lines as belonging to the complex projective plane, rather than the Euclidean plane. In this space, the points and lines form the perspective centers and axes of the perspective transformations of the Klein quartic.[6] They have the same pattern of point-line intersections as the Euclidean version of the configuration.

The finite projective plane has 57 points and 57 lines, and can be given coordinates based on the integers modulo 7. In this space, every conic (the set of solutions to a two-variable quadratic equation modulo 7) has 28 secant lines through pairs of its points, 8 tangent lines through a single point, and 21 nonsecant lines that are disjoint from . Dually, there are 28 points where pairs of tangent lines meet, 8 points on , and 21 interior points that do not belong to any tangent line. The 21 nonsecant lines and 21 interior points form an instance of the Grünbaum–Rigby configuration, meaning that again these points and lines have the same pattern of intersections.[7]

Properties

The projective dual of this configuration, a system of points and lines with a point for every line of the configuration and a line for every point, and with the same point-line incidences, is the same configuration. The symmetry group of the configuration includes symmetries that take any incident pair of points and lines to any other incident pair.[8] The Grünbaum–Rigby configuration is an example of a polycyclic configuration, that is, a configuration with cyclic symmetry, such that each orbit of points or lines has the same number of elements.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Grünbaum (2009, p. 156); Klein (1879); Burnside (1907); Coxeter (1983).

- ↑ Grünbaum (2009), p. 156.

- ↑ Grünbaum (2009), p. 13.

- ↑ Grünbaum (2009), p. 53.

- ↑ Grünbaum & Rigby (1990).

- ↑ Klein (1879). See transl. p. 297.

- ↑ Coxeter (1983).

- ↑ Grünbaum (2009), p. 363.

- ↑ Boben & Pisanski (2003).

References

- Boben, Marko; Pisanski, Tomaž (2003), "Polycyclic configurations", European Journal of Combinatorics, 24 (4): 431–457, doi:10.1016/S0195-6698(03)00031-3, ISSN 0195-6698, MR 1975946

- Burnside, W. (1907), "On the Hessian configuration and its connection with the group of 360 plane collineations", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series, 4: 54–71, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-4.1.54, MR 1576105

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1983), "My graph", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Third Series, 46 (1): 117–136, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-46.1.117, MR 0684825

- Di Paola, Jane W.; Gropp, Harald (1989), "Hyperbolic graphs from hyperbolic planes", Congressus Numerantium, 68: 23–43, MR 0995852. As cited by Grünbaum (2009).

- Grünbaum, Branko (2009), Configurations of points and lines, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, vol. 103, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, doi:10.1090/gsm/103, ISBN 978-0-8218-4308-6, MR 2510707

- Grünbaum, Branko; Rigby, J. F. (1990), "The real configuration (214)", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series, 41 (2): 336–346, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-41.2.336, MR 1067273

- Klein, Felix (1879), "Ueber die Transformation siebenter Ordnung der elliptischen Functionen", Mathematische Annalen, 14 (3): 428–471, doi:10.1007/BF01677143, S2CID 121407539. Translated into English by Silvio Levy as Klein, Felix (1999), "On the order-seven transformation of elliptic functions", The Eightfold Way, Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications, vol. 35, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 287–331, MR 1722419