Grandpa Indian (Portuguese: ⓘ) is a character conceived in the 1930s with the intention of replacing Santa Claus in Brazil. His aim was to inflate patriotic sentiments among the Brazilian population.[2] The dissemination of the character in the 1930s took place through the Integralist press, whose movement was rooted in Brazilian nationalism with fascist undertones. According to a chronicle in the 1934 Christmas edition of Correio da Manhã, Santa Claus would be deemed a "ridiculous figure" and out of place in a "land of warmth and intense sunlight", where "this chilly and stern old man was becoming impertinent".[3][4]

Depicted as an elderly gentleman who is "very friendly to the trees", adorned in "feathers of all the colors of the birds", who generously bestows gifts upon Brazilian children, Grandpa Indian faced criticism and mockery upon his debut, and by 1938 he had virtually disappeared.

History

Santa Claus did not exist in Brazil in the 19th century. His popularity started to grow in the early 20th century, with the first known image of him appearing on 24 December 1904. By 1908, Santa Claus had become synonymous with gift-giving, and in the 1930s he was firmly established among Brazilians. After World War I, Brazil witnessed the emergence of various nationalist cultural movements with diverse trends, particularly with the Modern Art Week festival in 1922. It is in this context that, at the end of the year 1932, around Christmas time, a nationalist initiative arose to overthrow Santa Claus, introducing in his place an indigenous creation, Grandpa Indian. This campaign, led by writer Christovam de Camargo, began in the newspaper O Globo.[1] On 28 November, this newspaper published a manifesto in defense of Grandpa Indian.[5][6]

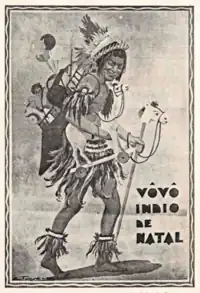

On 11 December 1932, the newspaper Correio da Manhã launched a contest to reward the best image of Grandpa Indian, and Christovam de Camargo himself presented his proposal in a manifesto. He stated that the belief in Santa Claus awakened, from a very young age, "the spirit of subservience and imitation";[7] some Brazilian nationalists were unhappy about the imposition of American Christmas traditions.[8] In February 1933, O Malho magazine featured an art by Euclides da Fonseca as the winning depiction of Grandpa Indian in the Correio da Manhã contest.[1][9]

According to historian Leandro Pereira Gonçalves, Grandpa Indian was a product of nationalist intellectual groups, predominantly associated with right-wing political ideologies, and was informally appropriated by Integralists. It is generally believed that Camargo created the character of Grandpa Indian.[1][4] Getúlio Vargas, who served as the president of Brazil during the periods of 1930–1945 and 1951–1954, had a fondness for the character. There are accounts that he wanted to turn Grandpa Indian into a Brazilian Christmas symbol, but there is little evidence that supports this claim. There have been reports that Vargas would have introduced Grandpa Indian in a stadium in Rio de Janeiro during a 1931 Christmas event, but the audience did not approve of the idea.[6]

In 1939, a theatrical production for children in Rio de Janeiro showcased an encounter between Santa Claus and Grandpa Indian. There were various accounts of people dressed as Grandpa Indian who brought gifts to children in the 1930s. In the 24 December 1932 edition of the O Globo newspaper, a report stated that the figure was responsible for delivering gifts at a school in Rio de Janeiro.[10] O Estado de S. Paulo reported in 1935 that Grandpa Indian delivered gifts to orphaned children. This action was promoted by the Public Force of São Paulo, an institution that preceded the current Military Police.[6]

Tradition

Grandpa Indian was portrayed by Christovam de Camargo as an elderly gentleman who is "very friendly to the trees", adorned in "feathers of all the colors of the birds", and who generously bestows gifts upon Brazilian children. He is said to have died "purely due to heartbreak" after envious White individuals expelled him from his land. In an attempt to associate him with Christianity, Grandpa Indian is believed to have arrived at the gates of the Catholic heaven. Saint Peter greets him, but laments he cannot gain entry, having not been baptized. Several angels sympathize with Grandpa Indian, and he is baptized with Saint Joseph and Mary, mother of Jesus as his godparents. After spending a few weeks in heaven, he starts to miss Earth and asks to occasionally make visits. Jesus Christ then appears and suggests sending Grandpa Indian to Brazil in his stead to distribute gifts to well-behaved children.[1][4][6]

Decline

Grandpa Indian was the target of criticism and mockery from the very beginning. In 1936, Correio da Manhã began accepting articles declaring the character defeated. In 1937, he was mentioned in only one article, and in 1938 in just two articles, both ironically, and virtually disappeared. In 1952, Rachel de Queiroz spoke of "xenophobic improvisations like that nonsense of 'Grandpa Indian' replacing Santa Claus".[11] In 1954, Gilberto Freyre characterized the episode involving Grandpa Indian as "an explosion of raw, naïve, and ridiculous nativism, similar to those patriots of the early 20th century who wanted to replace port wine with sugarcane aguardente".[1][12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Papiane, Matheus (2024). ""Vovô Índio": frustrada tentativa nacionalista de desbancar "Papai Noel" na década de 30 (e outras afins)" ["Grandpa Indian": frustrated nationalist attempt to dethrone "Santa Claus" in the 1930s (and similar ones)]. Revista Internacional d'Humanitats (in Portuguese). ISSN 1516-5485. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Bowler, Gerry (2020). "Culture Wars". In Larsen, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 576. ISBN 978-0-19-883146-4.

- ↑ Edmundo, Luiz (25 December 1934). "O FABULARIO DE VÔVÔ INDIO de CHRISTOVAM DE CAMARGO" [THE FABLES OF GRANDPA INDIAN by CHRISTOVAM DE CAMARGO]. Correio da Manhã (in Portuguese). p. 1. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 Balloussier, Anna Virginia (24 December 2019). "Brasil já teve Vovô Índio concorrente de Papai Noel; conheça" [Brazil once had Grandpa Indian as a competitor to Santa Claus; get to know him]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- 1 2 "Vamos fazer um Natal brasileiro?" [Shall we have a Brazilian Christmas?]. O Globo (in Portuguese). 28 November 1932. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Veiga, Edison (23 December 2021). "Há 90 anos, Vovô Índio era a tentativa brasileira de destronar Papai Noel" [90 years ago, Grandpa Indian was the Brazilian attempt to dethrone Santa Claus]. BBC News Brasil (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Camargo, Christovam de (11 December 1932). "SUBSTITUIÇÃO DE PAPÁ NOEL POR VOVÔ INDIO" [REPLACEMENT OF SANTA CLAUS WITH GRANDPA INDIAN]. Correio da Manhã (in Portuguese). p. 9. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Woodard, James P. (2021). "Empire by emulation: Brazilian business elites encounter the U.S. department store". History of Retailing and Consumption. 7 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1080/2373518X.2021.1935112. S2CID 237898019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023.

- ↑ "VÔVÔ INDIO" [GRANDPA INDIAN]. O Malho (in Portuguese). 11 February 1933. p. 6. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ "Vovô Indio entre as creanças" [Grandpa Indian among the children]. O Globo (in Portuguese). 24 December 1932. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Queiroz, Rachel de (20 December 1952). "NATAL DE 1952" [CHRISTMAS OF 1952]. O Cruzeiro (in Portuguese). p. 146. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Freyre, Gilberto (10 April 1954). "ABRASILEIRANDO PAPAI-NOEL" [BRAZILIANIZING SANTA CLAUS]. O Cruzeiro (in Portuguese). p. 24. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

External links

Media related to Grandpa Indian at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Grandpa Indian at Wikimedia Commons