Guðbrandur Þorláksson | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Hólar | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Church | Church of Iceland |

| Diocese | Hólar |

| See | Hólar |

| Appointed | 1571 |

| In office | 1571–1627 |

| Predecessor | Ólafur Hjaltason |

| Successor | Þorlákur Skúlason |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1541 Melstaður, Iceland |

| Died | 20 July 1627 Hólar, Iceland |

| Nationality | |

| Denomination | Lutheranism |

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

Guðbrandur Þorláksson or Gudbrand Thorlakssøn (c. 1542 – 20 July 1627) was bishop of Hólar from 8 April 1571 until his death. He was the longest-serving bishop in Iceland and is known for printing the Guðbrandsbiblía, first complete Icelandic translation of the Bible.

Early life

Guðbrandur was the son of Þorláks Hallgrímssonar, a priest based at Melstaður in Miðfjörður, and Helga Jónsdóttir, the daughter of the lawyer Jón Sigmundsson. Guðbrandur studied at Hólar College from 1553 to 1559 and then went to the University of Copenhagen where he studied theology and logic. Guðbrandur was one of the first Icelanders to study in Denmark instead of in Germany.[1] After returning to Iceland in 1564, he served as rector of the Skálholt School for three years before becoming a priest at historic Breiðabólstaður in Vesturhóp.[2][3]

Bishop

In 1571, the Danish King Frederick II named Guðbrandur Bishop of Hólar on the recommendation of Poul Madsen, bishop of Zealand, who had been his teacher in Copenhagen.[2] Guðbrandur served as bishop of Hólar for 56 years; no Icelander has held the position longer.

As bishop, Guðbrandur focused on cementing the Reformation in Iceland in part by working to publish holy works in Icelandic. He brought the printing press originally brought to Iceland by the Catholic priest Jón Arason to Hólar, printing nearly 100 books during his time as bishop.[4] He wrote and translated many works himself, including hymns and The Bible. Thanks to his printing work, as well as his focus on ensuring accuracy in translation, Guðbrandur is credited with helping strengthen the Icelandic language.[5]

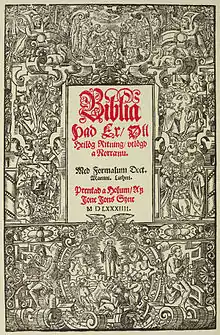

Printing of the Guðbrandsbiblía, or "Guðbrandur's Bible," was completed in 1584.[6] Portions included previous translations, including Oddur Gottskálksson's translation of the New Testament, along with new translations by Guðbrandur based on Latin, Germany, and Danish translations.[4] Although he worked with trained printers, Guðbrandur engraved some of the book's adornments himself.[2] Five hundred copies were printed, which were sold for the price of two or three cows.[7] The Guðbrandsbiblía was the basis for most Icelandic biblical translations until 1826.[8]

Other works published by Guðbrandur include a translation of Niels Hemmingsen's Liffsens Vey ("Way of Life") in 1575, the first Icelandic hymnal in 1589, an Icelandic Gradual in 1594, and the Vísnabók, a collection of spiritual songs, in 1612. He also published several writings by Arngrímur Jónsson.[2]

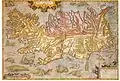

Guðbrandur was a well-rounded scholar with an interest in natural history, astronomy, and surveying, among other fields.[4] This led to his drafting of a new map of Iceland, which was published in Abraham Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum in 1590, as well as fixing the location of the island in the North Atlantic with greater accuracy than previous maps.[9] He also worked to ensure descriptions of Iceland were presented accurately to the world.[10]

Gallery of notable works

Guðbrandsbiblía in National Museum of Iceland, in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Guðbrandsbiblía in National Museum of Iceland, in Reykjavík, Iceland. One of his most important works: Map of Iceland

One of his most important works: Map of Iceland

Personal life

Soon after becoming bishop, Guðbrandur had a child with Guðrún Gísladóttir. Their daughter, Steinunn Guðbrandsdóttir, married the farmer Skúla Einarsson, and one of Skúla and Steinunn's sons, Þorlákur Skúlason, succeeded Guðbrandur as bishop of Hólar. On 7 September 1572, Guðbrandur married on Halldóra Árnadóttir (1547–1585), the daughter of Árni Gíslason, magistrate of Hlíðarenda, and Guðrún Sæmundsdóttir. Their children included Páll Guðbrandsson (1573–1621), Halldóra Guðbrandsdóttir (1574–1658), and Kristín Guðbrandsdóttir (1574–1652).

50 króna banknote

In 1981, the Central Bank of Iceland introduced a new series of banknotes with Guðbrandur on the front of the 50 Icelandic króna note and a fragment of the Guðbrandsbiblía and an image of early printers at work on the reverse. In 1987, the paper banknote was replaced with an IKr 50 coin.[11]

References

- ↑ Hastrup, Kirsten (1990). Nature and Policy in Iceland, 1400-1800: An Anthropological Analysis of History and Mentality. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827728-6. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Kaalund, Kristian (1902). "Thorláksson, Guðbrandur". In Bricka, Carl Frederik (ed.). Dansk Biografisk Lexikon [Danish Biographical Dictionary] (in Danish). Vol. XVII. pp. 272–274. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ "Breiðabólstaður (Historical Places in Northwest Iceland)". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 Stefán Einarsson (2019). A History of Icelandic Literature. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 125–130. ISBN 978-1-4214-3546-6. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ Ragnar Ingi Adalsteinsson (2014). Traditions and Continuities: Alliteration in Old and Modern Icelandic Verse. Reykjavík, Iceland: University of Iceland Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-9935-23-036-2. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ "Bible of Guðbrandur Þorláksson". The Hague, Netherlands: De KB Nationale Bibliotheek. Archived from the original on 5 November 2004.

- ↑ B.B. (1 September 1957). "Mestá bók á Íslandi" [The Biggest Book in Iceland]. Þjóðviljinn (in Icelandic). Vol. 22, no. 195. p. 3. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Edney, Matthew H.; Sponberg Pedley, Mary (2020). The History of Cartography, Volume 4: Cartography in the European Enlightenment. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-0-226-33922-1. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ Thorvaldur Thordarson (2010). "Perception of Volcanic Eruptions in Iceland". In Martini, I. Peter; Chesworth, Ward (eds.). Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 289. ISBN 978-90-481-9413-1. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ Emilía Dagný Sveinbjörnsdóttir (1 August 2018). "Hvaða fólk er á 10, 50 og 100 kr. seðlunum?" [What people are on 10, 50 and 100 kr. banknotes?]. The Icelandic Web of Science (in Icelandic). Retrieved 11 June 2020.