The Guayaquil Group (Grupo de Guayaquil, "Cinco como un puño") was a literary group from the 1930s - mid 1940s, that emerged as a response to a chaotic social and political climate where the Ecuadorian "montubio" and mestizo were oppressed by the elite class, priests, and the police. It was composed of five main writers: Joaquín Gallegos Lara, Enrique Gil Gilbert, Demetrio Aguilera Malta, José de la Cuadra, and Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco. Their works aimed to portray "social realism" as a form of displaying the real Ecuadorian montubio and cholo.[1] The group eventually disintegrates after the death of two of their writers, José de la Cuadra and Joaquín Gallegos Lara, the inactivity in literature by Enrique Gil Gilbert, and the long trips away from Ecuador by Demetrio Aguilera Malta and Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco in the mid 1940s.[2]

Origins

Historical Context

Stemming from an economy impacted by the liberalization of markets, the exploitation of the lower class became a prominent consequence of the open market economy of the pre-1930s. Clashes between classes resulted in the formation of two groups, the conservatives and the liberals. For the Ecuadorian mestizo in northern Ecuador, a main concern was the declining textile industry severely affected by the British textile industry.[3] Yet for the coast, especially in Guayaquil, the newly opened markets allowed for prosperity attributed to the increasing demand for cacao and the emergence of a new exporting class. As a result, the Ecuadorian economy found itself undergoing a "diversification of the regional production that came accompanied with a series of social changes that dislocated significantly the relationships between the dominant and the dominated, which was expressed in a series of regional social protests."[4][5]

Upon the ending of the first World War, a decline in the price of cacao and a plague in plantations, commence a concern for Ecuadorians. Emphasized by the global crisis during this period, Ecuadorian officials respond with a depreciation of their currency in efforts to maintain competitiveness among their products in the global market. This thus led to increasing unemployment rates and repression that incited the discontent of the working class. With great discontent, the Ecuadorian working class found themselves participating in a general strike on November 15, 1922, which was violently repressed resulting in around 1,200 to 1,500 people dead.[3][6]

Writing as a Response

For the principal writers of the Guayaquil Group, the violent repression of the strike struck a chord that remained with them until the 1930s. Their works served as a protest to the injustice carried out by those in power. In a speech, Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco discusses how the group came about:

"Los adolescentes y niños que, ocho años después, integraríamos el Grupo de Guayaquil, vimos espantados la bárbara matanza. Es apena obvio suponer que, parcialmente, cuando menos, aquel hecho brutal marcarse al resolución intima en nosotros de crear una literatura de denuncia y protesta. Lo cual nos condujo a poner una excesiva atención en el mundo exterior de las relaciones humanas. Porque, además, carecíamos de una ascendencia narrativa que hubiese puesto los ojos en los problemas de la tierra." [3] - Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco (Guayaquil Group Writer)

"The adolescents and children that, eight years later, would integrate the Guayaquil Group, saw in horror the barbarous killing. It's hardly obvious to suppose that, partially, at least, that brutal occurrence mark the intimate resolution within us to create a literature of denunciation and protest. Of which led us to pay excessive attention on the world exterior to human relationships. Because, in addition, we lacked the ascendency of a narrative that would have put its eyes on the problems of the land." [3] - Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco (Guayaquil Group Writer)

This was the reason for the works produced during this period being focused largely on dialogue and representing the true Ecuadorian "montubio", and "cholo." The group came to represent the "first modern effort in the Ecuadorian novel that focused on the inhabitants of the coast as a source of artistic interpretation."[7] With that in mind, the writers attempted to maintain artistic sense and social conscience in a balance that would undermine one over the other. Not only were they attempting to maintain a certain balance of senses, but they wanted to somehow keep their works distanced from political labels doing so by putting an emphasis on the characters and making them something beyond stereotypes. The works focused on humanizing the "montubio" and "cholo" to the point of presenting the injustices they experienced to the reader without a lineal narrative.[8]

Yet for these writers, the name "Guayaquil Group" is not one they placed on themselves. According to Demetrio Aguilera Malta, their nation had deemed them so and after the success of the work: Los que se van (1930), they went around and outside of the country with that denomination.[9]

By 1936, the Society of Writers and Independent Artists was formed as an extension of the Guayaquil Group. Leopoldo Benites Vinueza and Abel Romeo Castillo, were among the new additions to the literary group.[3]

Members

Joaquín Gallegos Lara was considered the spiritual guide of the group with immense intellectual capacity. He was born with a physical defect that made him use a wheelchair for most of his life. Despite his disability, he found himself working many bureaucratic jobs but during the last 10 years of his life, he worked on a cart transporting merchandise across the country from the city to the mountains. This exposed him to several groups of people where he develops friendships with montubios, giving him enough material for the novel "Los que se van." Yet his family was of low social standing which attracted him to Marxism.[10] As a member of the Communist Party, he felt like his experiences impeded him from writing fiction prompting him to social realism.[2] At the age of 16, he publishes his first poems.

The youngest member of the group. He found himself attracted to Marxism and became a militant member of the Communist Party. Publishes his first poems at the age of 16.[11] By his counterparts, he was considered an idealist and found himself identifying with the working class despite his family being of higher social standing. He was rebellious and an active participant in the political scene throughout his college career. His activism forces him out of college thereafter leading him to traveling around Ecuador where he spent a lot of time with families in the country exposing him montubios. This gave him the necessary material to write with in his novelas, short stories, and poems.[2]

Member of the Socialist Party who later abandons his political activity to focus on his writing, theatre and film. He was considered the most versatile member of the group due to his ability to manifest his works in a variety of forms like: novels, short stories, poems, theatre, sculptures, and war reports.[11] Early on, he was active in politics and social reform. His family was of middle-class background which allowed him to travel around Ecuador with his father. This exposed him to various areas of the Ecuadorian coast where he met "cholos," serving as the inspiration for his writing.[2]

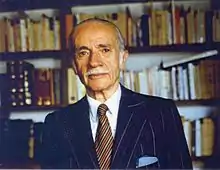

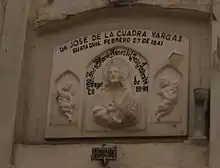

José de la Cuadra was the oldest member of the group that found his death at 37 years old. He was the first to die from this group. De la Cuadra is often considered to have developed artistically throughout his career within the Guayaquil Group. He was a member of the Socialist Party. By the age of 17, he begins to publish his poems.[12] As a lawyer, he found himself often serving "montubios" in criminal cases which exposed him to several ethnic-social groups giving him the necessary material for his writings.[2]

Considered to be the most adaptive to situations, Pareja Diezcanseco's background is aristocratic yet his family's social standing descends to middle class after his father's death. Although he was the one to receive the least amount of formal education, he was able to reach the most education by adulthood. He was also the most prolific of the group. Pareja Diezcanseco was not a part of any political party but had socialist leanings. At the age of 17, he begins writing. Most of his works are urban and demonstrate the relationship that he had with a variety of social classes.[2]

List of Most Recognized Works

A series of stories by Demetrio Aguilera Malta, Joaquín Gallegos Lara, and Enrique Gil Gilbert. Discuses themes surrounding military slavery, feudal slavery.[13] The stories make explicit use of common vernacular noted mostly by the use of curses.[14] Obtained international attention because it was one of the first works with contemporary prose that would set the precedence for future Ecuadorian literature. According to Karl Heise, "Ecuadorian literature is famous during this period due to its social emphasis, in this book, the treatment of the social phenomenons is present, but not prevalent. The authors desired to tell good stories and attempt to do them well."[15] There are no stylistic differences in this collection of stories and without the names of the authors being there it would be quite impossible to distinguish who wrote each story. The collection of stories manages to focus on three things: the environment as a physical and spiritual entity, the camaraderie within the social groups, and society in general. This work makes an attempt to capture a way of life that the authors thought was en route to going extinct, hence the need to write about montubios and cholos.[16][17]

Horno (1932)

Written by José de la Cuadra. Made up of two editions, the first of which contains 11 stories and was published in 1932. The second edition contains 12 stories, published in 1940. Most famous work within this piece is, The Tigress, which appears only in the second edition.[12] Themes include passion, violence, homicide, cruelty and revenge, but also the vindication of the disgraced in Ecuador.

Nuestro pan (1941)

Written by Enrique Gil Gilbert.

Don Goyo (1933)

Written by Demetrio Aguilera Malta. Emphasizes the relationship between the worker and the soil with particular symbolism found in the rice field that the "cholo peon" Cusumbo is working on.

Los Sangurimas (1934)

Written by de la Cuadra. It's a short story comparing a tree, the "matapalo," to the Ecuadorian "montubio."

Other works

Rio Arriba (1932)

El Muelle (1933)

La Beldaca (1935)

Baldomera (1938)

Yunga (1933)

Las cruces sobre el agua (1946)

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

For the writers of the Guayaquil Group, their legacy lived on in their works. Yet, during their time of writing, they didn't necessarily find themselves changing the social conditions of the time. With their writings, they had at most hoped to bring attention to the injustices carried out by those in power. The production of their works were meant as a protest that "hoped to awaken public indignation about the situation that was largely ignored by those in power."[18] The usage of crude themes like violence and sex, in fact, ended up alienating those that could have joined the social reform movement. For others, these stories were read for entertainment leaving those being criticized within the works feeling unaffected. At the same time, however, the stories written by the group, did manage to accelerate movement towards developing some reforms.[19]

- Monument for the writers of the Guayaquil Group, named "Cinco como un puño."[20] Found in Guayaquil, Ecuador in the Malecón

References

- Heise, Karl H. (1975), El grupo de Guayaquil: Arte y tecnica de sus novelas sociales, Madrid: Coleccion Nova Scholar.

- ↑ "El Grupo de Guayaquil y su huella". El Comercio. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Heise, Karl (1975). El grupo de Guayaquil: arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. pp. 19–27. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pareja Diezcanseco, Alfredo (1989). "Los Narradores del Grupo Guayaquil" (PDF). AFESE. 17.

- ↑ Rueda, Sonia Fernández (2006-01-01). "La escuela activa y la cuestión social en el Ecuador: dos propuestas de reforma educativa, 1930-1940". Procesos. Revista ecuatoriana de historia (in Spanish). 1 (23): 77–96. ISSN 1390-0099.

- ↑ Benavides, Hugo (2006). Politics of Sentiment. University of Texas Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780292795907.

- ↑ Cueva, Agustín (1988-12-30). "Literatura y sociedad en el Ecuador: 1920-1960". Revista Iberoamericana. 54 (144): 629–647. doi:10.5195/reviberoamer.1988.4477. ISSN 2154-4794.

- ↑ Heise, Karl (1975). El grupo de Guayaquil: Arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. p. 17. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

first modern effort in the Ecuadorian novel that focused on the inhabitants of the coast as a source of artistic interpretation.

- ↑ Pareja, Miguel Donoso (1988-12-30). "La literatura de protesta en el Ecuador". Revista Iberoamericana. 54 (144): 977–999. doi:10.5195/reviberoamer.1988.4500. ISSN 2154-4794.

- ↑ Fama, Antonio; Aguilera-Malta, Demetrio (1978-01-01). "Entrevista con Demetrio Aguilera-Malta". Chasqui. 7 (3): 16–23. doi:10.2307/29739436. JSTOR 29739436.

- ↑ Robles, Humberto E. (1988-12-30). "La noción de vanguardia en el Ecuador: Recepción y trayectoria (1918-1934)". Revista Iberoamericana. 54 (144): 649–674. doi:10.5195/reviberoamer.1988.4478. ISSN 2154-4794.

- 1 2 "Grupo Guayaquil: Cinco como un puñado de poemas | La Revista | EL UNIVERSO". www.larevista.ec (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- 1 2 PAREJA DIEZCANSECO, Alfredo (1980-01-01). "El mayor de los cinco". Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien (34): 117–139. JSTOR 43687364.

- ↑ Crooks, Esther J. (1940-01-01). "Contemporary Ecuador in the Novel and Short Story". Hispania. 23 (1): 85–88. doi:10.2307/332662. JSTOR 332662.

- ↑ Méndez, Jorge Estévez. "Ecuador online - Hombres Notables del Ecuador (Demetrio Aguilera Malta)". www.explored.com.ec. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ↑ Heise, Karl (1975). El grupo de Guayaquil: arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. pp. 34–35. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

Ecuadorian literature is famous during this period due to its social emphasis, in this book, the treatment of the social phenomenons is present, but not prevalent. The authors desired to tell good stories and attempt to do them well.

- ↑ Heise, Karl (1975). "Los Que Se Van". El grupo de Guayaquil: arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. pp. 33–48. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

- ↑ Robles, Humberto E. (1988-12-30). "La noción de vanguardia en el Ecuador: Recepción y trayectoria (1918-1934)". Revista Iberoamericana. 54 (144): 649–674. doi:10.5195/reviberoamer.1988.4478. ISSN 2154-4794.

- ↑ Heise, Karl (1975). El grupo de Guayaquil: Arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. p. 125. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

hoped to awaken public indignation about the situation that was largely ignored by those in power.

- ↑ Heise, Karl (1975). "El legado del << Grupo de Guayaquil >> y la novela contemporanea". El grupo de Guayaquil: Arte y técnica de sus novelas sociales. Madrid, Spain: Colección Nova Scholar. pp. 125–146. ISBN 84-359-0120-3.

- ↑ "Monumento a los Escritores Guayaquileños "Cinco como un puño"". www.guayaquilesmidestino.com. Retrieved 25 April 2017.